An even more serious problem is that bacteria can become resistant

An even more serious problem is that bacteria can become resistant

Test 5

Task 1. READING

WHEN A COMPUTER ERROR IS A FATAL MISTAKE

Our lives depend on computers. They control our money, transport, our exam results. Yet their programs are now so complex that no one can get rid of all the mistakes.

Life without computers has become unimaginable. They are designed to look after so many boring but essential tasks — from microwave cooking to flying across the Atlantic — that we have become dependent on them.

But as the demands placed on computers grow, so have the number of incidents involving computer errors. Now computer experts are warning that the traditional ways of building computer systems are just not good enough to deal with complex tasks like flying planes or maintaining nuclear power stations. It is only a matter of time before a computer-made catastrophe occurs.

As early as 1889, a word entered the language that was to become all too familiar to computer scientists: a ‘bug’, meaning a mistake. For decades bugs and ‘de-bugging’ were taken to be part of every computer engineer’s job. Everyone accepted that there would always be some mistakes in any new system. But ‘safety critical systems that fly planes, drive trains or control nuclear power stations can have bugs that could kill. This is obviously unacceptable.

One way to stop bugs in computer systems is to get different teams of programmers to work in isolation from each other. That way, runs the theory, they won’t all make the same type of mistake when designing and writing computer codes. In fact research shows that programmers think alike, have the same type of training — and make similar mistakes. So even if they work separately, mistakes can still occur. Another technique is to produce back up systems that start to operate when the first system fails. This has been used on everything from the space shuttle to the A320 airbus, but unfortunately problems that cause one computer to fail can make all the others fail, too.

A growing number of computer safety experts believe the time has come to stop trying to ‘patch up’ computer systems. They say programmers have to learn to think clearly and to be able to demonstrate through mathematical symbols that the program cannot go seriously wrong. Until programmers learn to do this, we will probably just have to live with the results of computer bugs.

Of course, more often than not the errors are just annoying, but sometimes they can come close to causing tragedies. On the Piccadilly line in London’s Underground a driver who was going south along a track got confused while moving his empty train through a cross-over point. He started to head north straight at a south-bound train full of people. The computerized signaling system failed to warn him of impending disaster and it was only his quick human reactions that prevented a crash.

| A | Experts say «Bring back math!» |

| B | Old methods are no longer satisfactory |

| C | We couldn’t live without computer |

| D | Hotels are carefully classified |

| E | An old problem with serious consequences |

| F | A potentially disastrous mistake |

| G | Self-catering accommodation comes |

| H | Whether two new approaches solve the problem. |

Task 2. READING

Read the text below. For questions (6 – 11) choose the correct answer (A, B, C or D).

WHEN YOU HAVE A SORE THROAT

What causes a sore throat?

Many things can cause a sore throat. These causes include infections with viruses or bacteria, or sinus drainage and allergies, among others. You should see your doctor right away if you have a sore throat with a high fever, if you have problems breathing or swallowing, or if you feel very faint. If you have a sore throat and a fever, but you just feel mildly ill, you should visit your doctor within the next day or two. If you have a cold with sinus drainage, you may use over-the-counter medicines, like Sudafed or Actifed. Visit your doctor if this cold lasts for more than two weeks, or if it gets worse.

How does the doctor decide if I need antibiotics?

The decision to prescribe antibiotics might be based only on your history and physical exam. Antibiotics usually are prescribed only for patients who might have «strep throat», an infection caused by a bacteria called Streptococcus. A patient with strep throat might have a sore throat with fever that starts suddenly, without a cough or cold symptoms. Strep throat is very common in children from 5 to 12 years of age. The exam might show a red throat, with pus on the tonsils and swollen neck glands. If you have these signs, the doctor may do other tests to see if you need an antibiotic.

Why not just give everyone antibiotics?

Antibiotics have a small risk of causing an allergic reaction every time they are given. Some of these reactions are serious. Antibiotics can also cause other side effects, such as an upset stomach or diarrhea. An even more serious problem is that bacteria can become resistant to antibiotics if these medicines are used frequently in a lot of people. Then antibiotics wouldn’t be able to cure people’s illnesses. To prevent this from happening, doctors try to prescribe antibiotics only when they will help. Antibiotics only help when sore throat is caused by bacteria. Antibiotics don’t help when sore throat is due to viruses, which are the cause of the common cold.

If my doctor doesn’t give me antibiotics, what can I do to feel better?

It will take several days for you to feel better, no matter what kind of sore throat you have. You can do several things to help your symptoms. If you have a fever or muscle aches, you can take a pain reliever like acetaminophin (Tylenol), aspirin or ibuprofen (Advil). Your doctor can tell you which pain reliever will work best for you. Cough drops or throat sprays may help your sore throat. Sometimes gargling with warm salt water helps. Soft cold foods, such as ice cream and popsicles, often are easier to eat. Be sure to rest and to drink lots of water or other clear liquids, such as Sprite or 7-Up. Don’t drink drinks that have caffeine in them (coffee, tea, colas or other sodas).

Should I be concerned about any other symptoms that occur after I visit my doctor?

Sometimes symptoms change during the course of an illness. Visit your doctor again if you have any of the following problems:

Fever that does not go away in five days

Throat pain that gets so bad you can’t swallow

Inability to open your mouth wide

A fainting feeling when you stand up

Any other signs or symptoms that concern you

This information provides a general overview on sore throat and may not apply to everyone. Talk to your family doctor to find out if this information applies to you and to get more information on this subject.

Task 3. READING

Never more in need of leadership, the Football Association is finally close to appointing a successor to Adam Crazier.

The largest teaching union has pledged to boycott «disgusting» national tests for seven, 11 and 14-year-olds.

National Union of Teachers delegates voted unanimously in favour of the attack on a key Government education policy at the union’s annual conference in Harrogate.

Conservatives made strong gains in local elections across England yesterday, bolstering the party’s battered morale and shoring up Lain Duncan Smith’s position as leader.

British Airways yesterday admitted it was having to cut ticket prices heavily to fill its planes as it revealed a sharp fall in front-of-cabin traffic last month, hit by particularly tough trading conditions.

Hungry Eleri Nicholas was about to tuck into a bowl of Tesco salad — when a locust crawled out. Housewife Eleri, 26, screamed as the four-inch insect crept out of the salad leaves and looked up at her.

Horrified Eleri said: «It was grey and horrible — like something from a horror movie». Consumer watchdogs were yesterday investigating the creepy-crawly which popped out from a ready-to-serve bag of Italian salad.

Eleri had eaten half of the salad the previous night — and was about to finish it off when the plant-eating insect suddenly appeared.

| A | Minister holds talks with CAA about troubles at MyTravel |

| B | Refusal to be involved in the procedure of evaluating teens’ performance. |

| C | SBS team’s tank ordeal |

| D | Need for a leader to be in charge. |

| E | Slashing seat prices as first-class cabin empties |

| F | How Brits get their kinky kicks |

| G | Gaining support at polls. |

| H | Gnat in the cold meal |

Task 4. READING

CATCHING A COLD

Many people catch a cold in the springtime and/or fall. It makes us wonder. if scientists can send a man to the moon, why can’t they find a cure for the common cold. The answer is easy. There are literally hundreds of kinds of cold viruses out there. You never know(17)________.

When (18)________, your body works hard to get rid of it. Blood rushes to your nose and brings congestion with it. (19)________, but your body is actually «eating» the virus. Your temperature rises and you get a fever, but the heat of your body is killing the virus. You also have a runny nose to stop the virus from getting to your cells. You may feel miserable, (20)________.

Different people have different remedies for colds. In the United States(21)________, people might eat chicken soup to feel better. Some people take hot baths and drink warm liquids. Other people take medicines to stop the fever, congestion, and runny nose.

If takes about 1 week to get over a cold if you don’t take medicine, but only 7 days to get over a cold if you take medicine.

| A | but actually your wonderful body is doing everything it can to kill the cold |

| B | a virus attacks your body |

| C | which one you will get, so there isn’t a cure for each one |

| D | the old lady |

| E | You feel terrible because you can’t breathe well |

| F | a large kitchen with cookies |

| G | and some other countries, for example |

| H | an amazing job on their own |

Task 5. USE OF ENGLISH

Read the text below. For questions (23 – 34) choose the correct answer (A, B, C or D).

THE IDEA

Andy Wasnick loved the idea. Mary Arthur hated it. Kurt Mendez didn’t think it was any big (23)__________. Mr.El thought it was a brilliant idea. After all, it was his idea.

«It’s only fair», Mr. El (24)________ to his new fourth graders as they stood (25)________ waiting for the lunch bell to ring, «that we turn things around. Every year you guys line up in alphabetical (26)________. Alphabetical order to go to lunch, to go to gym, to go home, and so on. This year we’re using (27)________ alphabetical order».

Mindy Vale put her hand down as Mr. El pointed to her. «I’ve always had to stand at the (28)________ of the line, ever (29)________ kindergarten! Now I’m near the front. Thank you, thank you!»

The teacher smiled. Then he called on Christopher Cash, a serious and (30)________ young man. «Mr. El, I think you should reconsider this policy. This is very drastic and (31)________.

This could confuse our fragile young minds!»

«Put a lid on it, Chris!» shouted David Tyler.

«We won’t have any outbursts like that, David!» Mr. El said firmly. He turned toward Christopher. «Don’t (32)________, Christopher. We only have strong minds in this class».

«How many of you think this is a good idea?» Mr. El asked. As you would probably (33)________, most of the hands that went up were in the (34)________ half of the line.

| # | A | B | C | D |

| 23 | bargain | deal | business | agreement |

| 24 | described | taught | told | explained |

| 25 | in line | in queue | in view | in turn |

| 26 | letters | series | order | index |

| 27 | upside down | reverse | inside out | backwards |

| 28 | back | bottom | nape | rear |

| 29 | in | since | off | as |

| 30 | absorbed | thoughtful | philosophical | involved |

| 31 | superflous | excess | unnecessary | redundant |

| 32 | move | worry | scream | speak |

| 33 | expect | doubt | forget | review |

| 34 | start | rise | beginning | front |

Task 6. USE OF ENGLISH

Read the text below. For questions (35 – 46) choose the correct answer (A, B, C or D).

STEVEN SPIELBERG

| # | A | B | C | D |

| 35 | Much | More | Most | The most |

| 36 | likelyb | as if | like | as |

| 37 | on the age | at the age | in the age | with the age |

| 38 | longest | longer | length | long |

| 39 | Making | Make | Having made | made |

| 40 | enough well | well enough | good enough | enough good |

| 41 | asked for | has asked for | asked | was asked for |

| 42 | complication | complicated | complicating | complicate |

| 43 | to create | can create | created | make create |

| 44 | would be won | to win | won | win |

| 45 | is | was | are | were |

| 46 | looked | looking | looks | look |

Writing

Imagine that you are planning a business trip to Edinburg. Write the letter to the Chapman Company, to Mr. Henry Smith; In your letter

thank him for the invitation you to the business forum

notify him about your arrival (the date, number of train, coach, time of arrival)

ask him to arrange for a company representative to meet you.

Write at least 100 words. Do not write any dates and addresses. Start your letter with

Answers:

1.B; 2.E; З.Н; 4.A; 5.F; 6.B; 7.A; 8.C; 9.C; 10.B; 11.D; 12.D; 13.B; 14.G; 15.E; 16.H; 17.C; 18.B; 19.E; 20.A; 21.G; 22.H; 23.B; 24.D; 25.A; 26.C; 27.В; 28.A; 29.В; З0.В; 31.C; 32.В; 33.A; 34.D; 35.D; 36.C; 37.B; 38.D; 39.A; 40.C; 41.A; 42.В; 43.В; 44.C; 45.A; 46.D

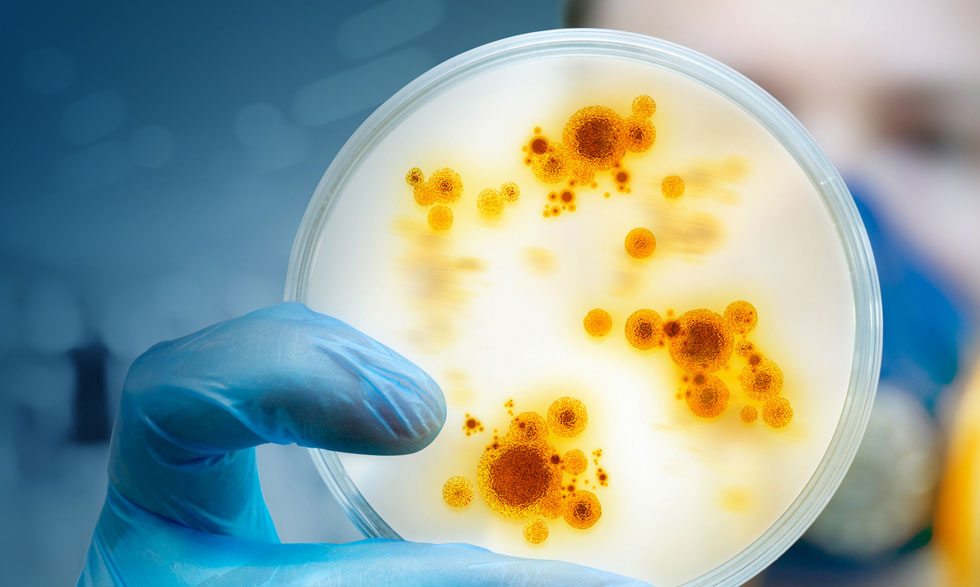

The end of antibiotics?

Over-prescribed and misused, these wonder drugs are leading to widespread drug resistance

«If you are given antibiotics, you will kill all the sensitive bacteria. Most of the ones that will survive will be the resistant ones.»

For the past 70 years, antimicrobial drugs, such as antibiotics, have successfully treated patients with infections. But over time, many infectious organisms have adapted to the drugs that kill them, making them less effective. Overusing or misusing these drugs can make resistance develop even faster.

Each year in the U.S. at least 2 million people become infected with bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics. At least 23,000 people die annually as a direct result of these infections. Many more people die from complications of antibiotic-resistant infections.

To address this growing problem, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) is working to speed the development of faster ways to detect resistance and ultimately to find new treatments that are effective against these drug-resistant bacteria.

Drug-Resistant Bacteria: On the Edge of a Crisis

Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., has been the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) since 1984. He helped pioneer the field of human immunoregulation, or the control of specific immune responses and interactions. He has also advised five presidents and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on HIV/AIDS and many other health issues. He spoke to NIH MedlinePlus magazine to discuss NIAID’s drug-resistant bacteria research program.

Why are certain bacteria becoming more resistant to drugs?

There is a multi-part answer to that question. One of the most important reasons is that bacteria generally mutate—all microbes mutate—naturally and spontaneously. However, you can do things that pressure them to mutate even more and develop resistance to drugs.

One of the major factors in certain bacteria becoming resistant to drugs today is the overuse of antibiotics, particularly the inappropriate use of antibiotics. This includes using antibiotics when you do not really have to—either when you have a viral infection that you think is bacterial and treat it with an antibiotic, or you treat someone with the wrong antibiotic that is not particularly suited to the bacteria in question.

In other words, if you are given antibiotics, you will kill all the sensitive bacteria. Most of the ones that will survive will be the resistant ones.

You and other experts in the field have said that we are on the edge of a national, even global crisis of drug-resistant bacteria. Why is that?

The more we see this growing problem of antimicrobial resistance throughout the world, the more we will begin to see bacteria that are relatively untreatable or very, very difficult to treat. And if those bacteria become very widespread, that could lead to a serious crisis.

What might such a situation look like to most people?

A typical, real-life example would be someone gets a surgical procedure like a hip or knee replacement, or goes to the hospital for abdominal surgery. Then they get an infection that happens to come from another hospital patient who has resistant bacteria. What should be a routine procedure could lead to an infection that you struggle to treat, and you end up with a high degree of morbidity or even mortality. The routine surgical case becomes a medical emergency.

What kinds of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria are common in the U.S.?

We still have the problem of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which is disturbing. Another one that is also disturbing is called Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, or CRE. That is a growing problem. We see that in hospital patients who are immunosuppressed as a result of, for example, transplants or drugs that suppress their cancer or their inflammatory disease. Another bacteria that causes infections when antibiotics are overused is Clostridium difficile (C. Difficile), which we see a lot of in nursing homes and hospital settings.

Those three are big ones—MRSA, CRE, and C. Difficile. And, depending on the population in question, globally we are seeing more and more resistance to gonorrhea, a sexually transmitted disease.

How is NIAID approaching research to help solve the challenges associated with antimicrobial resistance?

Our research spans a wide range of activities, starting with understanding the molecular basis of how bacterial resistance evolves.

The second thing we are doing is a molecular analysis of microbes to determine what the targets are for resistance and for new antibiotics. Another is to develop new, unique ways of combating bacteria, such as understanding how microbes survive in different environments and exploiting that to fight them.

We also spend a lot of time working with the pharmaceutical companies on concept development towards the ultimate development of new antibiotics. While new antibiotics will ultimately be made by pharmaceutical companies, NIH and NIAID have a basic, fundamental role in the clinical and applied research and development of these new antibiotics.

How to Solve the Problem of Antibiotic Resistance

Nobelist Venki Ramakrishnan recommends an array of steps, including international cooperation

«data-newsletterpromo_article-image=»https://static.scientificamerican.com/sciam/cache/file/4641809D-B8F1-41A3-9E5A87C21ADB2FD8_source.png»data-newsletterpromo_article-button-text=»Sign Up»data-newsletterpromo_article-button-link=»https://www.scientificamerican.com/page/newsletter-sign-up/?origincode=2018_sciam_ArticlePromo_NewsletterSignUp»name=»articleBody» itemprop=»articleBody»>

SA Forum is an invited essay from experts on topical issues in science and technology.

Editor’s note: This is the last of a series of interviews with leading scientists, produced in conjunction with the World Economic Forum on the occasion of last week’s conference in Davos, Switzerland; interviews for the WEF by Katia Moskvitch.

Antibiotics have saved millions of lives—but their misuse and overuse is making them less effective as bacteria develop resistance. Despite scientists’ warnings, antibiotic prescriptions in many countries continue to soar.

Venki Ramakrishnan, a Nobel Prize-winning chemist based at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology at the University of Cambridge, tells us about the importance of gaining a better understanding of the use and misuse of these wonder drugs.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows.]

The world seems to be running out of antibiotics. In middle of the 20th century more than 20 new classes of antibiotics were marketed; since the 1960s only two new classes have reached the market. Why is that the case?

It’s not entirely clear. Because of the effort to make penicillin during World War II, and its success, there was a strong motivation to look for other antibiotics. So in the ’40s and ’50s there were lots of new antibiotics that were being discovered.

But then it became a law of diminishing returns for the number of new compounds that could be effective. Being able to kill bacteria is not enough; you have to be able to make an antibiotic cheaply, and it has to be safe. So the number of really new compounds diminished and a lot of drug companies were modifying known antibiotics, trying to make them better and more effective.

There have been recent reports of a breakthrough—a new antibiotic that “kills pathogens without detectable resistance.” What do you think of this advance?

Indeed, there was a very interesting report on an antibiotic from a soil bacterium that does represent a new class. Many bacteria cannot be cultured but the researchers used a clever trick to obtain a reasonable amount of this bacterium and isolate a new class of antibiotics from it. How useful it will be in humans still remains to be seen, because it has to go through the clinical trials.

The other issue is resistance. In the paper they claim that this antibiotic, because of the way it acts, is unlikely to lead to resistance. But people have said this about many different things before, and eventually resistance seems to develop. I would be a little cautious to say that no resistance will ever develop to anything, because natural selection is very powerful and has a way of defeating even the most powerful tools. Still, it seems very promising.

Researchers are now waging a war against antibiotic-resistant bacteria. What exactly is being done?

There are several aspects to the problem of antibiotic resistance. It’s very important to have highly specific targets, which kill the particular bacterium that’s causing the disease rather than using a spectrum of antibiotics that should only be used as a last resort when you don’t know what the disease is caused by and you don’t have time.

But there’s a larger problem—the problem of resistance is also due to an abuse of antibiotics. Many people will go to a doctor and demand an antibiotic when they have a cold or a flu, for which these antibacterial compounds are useless. In many countries it is possible to buy antibiotics over the counter. Often, if people are poor, they will not take the full dose—all of that leads to resistance.

In countries like India people will give you antibiotics prophylactically, as a way to prevent infection. This should only be done in very extreme cases because it’s again spreading resistance.

So is the problem limited mostly to the developing world?

Not at all—in addition to also prescribing antibiotics for the flu the West, agriculture uses antibiotics in feed to fatten up the cattle—that’s an abuse of antibiotics. This leads to the spread of resistant strains, rendering current antibiotics useless if resistance spreads too much.

We need better diagnostics, to allow us to very quickly diagnose a bacterium that is causing a particular disease, to then treat it specifically with a narrow spectrum of antibiotics. And finally, there’s a whole issue of better public hygiene.

People now move all over the world, so if resistance emerges in one place it can very quickly spread to other places. So it needs a concerted attack—it is a broad social problem.

Are you confident we can win this war against resistant bacteria?

I am an optimist. I think that when things get serious, people have a habit of responding. And I’m hoping that people don’t wait for a big crisis to respond because then a lot of people will die before things will get corrected and improve.

I would prefer that governments in a worldwide agreement establish certain guidelines for antibiotics use—for public health, for hygiene, for use of antibiotics in the animal industry; and also will promote science—get better diagnostics, better understanding of how bacteria cause disease and for the development of new antibiotics.

What would a world without antibiotics look like?

I don’t think there ever will be a world without antibiotics. In a worst-case scenario, if resistant strains emerge to all known antibiotics, there will be large epidemics until new antibiotics are found. It won’t be like returning to the dark ages because now we have a huge amount of knowledge about how bacteria work, about molecular biology, genetics, microbiology and about how to make antibiotics. But we have to be proactive.

Are there any alternatives to antibiotics?

Antibiotics should be used as a last resort. Apart from general preventive measures like public health and hygiene, vaccines can be of enormous benefit. If we can develop good vaccines for many serious diseases, that would be wonderful. However, vaccine development is a difficult enterprise and it can take a long time in any given case. Sometimes it has failed despite many years of work.

Bacteriophages—naturally occurring viruses that attack specific bacteria—have sometimes been mentioned as possible tools. Although they were discovered in the early 20th century, their clinical use has so far been limited to some efforts in Russia, [the Republic of] Georgia and Poland. This is partly because they are large biological agents, and delivering the phage to the appropriate target is not as straightforward as administering a small-molecule antibiotic. Phages and bacteria can also mutate, rendering them ineffective. However, it is possible that future research may pave the way for greater use of phages to treat bacterial infections.

Are governments and the public beginning to understand the problem with resistant bacteria and do something about it?

I think so. Of course, when resistance becomes a huge problem and starts affecting the middle class and the rich, there will be an outcry. But I think things are already changing. In India, for instance, I see a lot of opinions for stricter regulations of antibiotics and for their better use. But India has a huge problem of providing proper sanitation and public health, and that’s a big problem to be tackled.

It’s a multipronged approach. Measures like public health and hygiene will take a long time.

Do you think the production of drugs should be funded by governments or by private companies, as it is mostly the case today?

I personally believe that for certain things the private enterprise model is not going to work. It costs a huge amount of money to develop a new drug. But when you develop a new antibiotic, one of the first things you’re told is only to use it against resistant strains as a last resort. And that itself limits the number of patients who can take this medicine—and that limits your income.

If it’s a good antibiotic, the patient will be cured in a week or two—whereas ideally if you want to make a lot of money from a drug, it should be something the patient has to take all of their life. So antibiotics by their nature are not going to be the same class of moneymaker.

So I think that governments really need to get involved in the development of new antibiotics. They have to think of this as something generally good for society, the same reason that governments fund education, roads, police, defense and so on. This is one case where governments need to act.

Antibiotic resistance

Key facts

Introduction

Antibiotics are medicines used to prevent and treat bacterial infections. Antibiotic resistance occurs when bacteria change in response to the use of these medicines.

Bacteria, not humans or animals, become antibiotic-resistant. These bacteria may infect humans and animals, and the infections they cause are harder to treat than those caused by non-resistant bacteria.

Antibiotic resistance leads to higher medical costs, prolonged hospital stays, and increased mortality.

Scope of the problem

Antibiotic resistance is rising to dangerously high levels in all parts of the world. New resistance mechanisms are emerging and spreading globally, threatening our ability to treat common infectious diseases. A growing list of infections – such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, blood poisoning, gonorrhoea, and foodborne diseases – are becoming harder, and sometimes impossible, to treat as antibiotics become less effective.

Where antibiotics can be bought for human or animal use without a prescription, the emergence and spread of resistance is made worse. Similarly, in countries without standard treatment guidelines, antibiotics are often over-prescribed by health workers and veterinarians and over-used by the public.

Without urgent action, we are heading for a post-antibiotic era, in which common infections and minor injuries can once again kill.

Prevention and control

Antibiotic resistance is accelerated by the misuse and overuse of antibiotics, as well as poor infection prevention and control. Steps can be taken at all levels of society to reduce the impact and limit the spread of resistance.

Individuals

To prevent and control the spread of antibiotic resistance, individuals can:

Policy makers

To prevent and control the spread of antibiotic resistance, policy makers can:

Health professionals

To prevent and control the spread of antibiotic resistance, health professionals can:

Healthcare industry

To prevent and control the spread of antibiotic resistance, the health industry can:

Agriculture sector

To prevent and control the spread of antibiotic resistance, the agriculture sector can:

Recent developments

While there are some new antibiotics in development, none of them are expected to be effective against the most dangerous forms of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Given the ease and frequency with which people now travel, antibiotic resistance is a global problem, requiring efforts from all nations and many sectors.

Impact

When infections can no longer be treated by first-line antibiotics, more expensive medicines must be used. A longer duration of illness and treatment, often in hospitals, increases health care costs as well as the economic burden on families and societies.

Antibiotic resistance is putting the achievements of modern medicine at risk. Organ transplantations, chemotherapy and surgeries such as caesarean sections become much more dangerous without effective antibiotics for the prevention and treatment of infections.

WHO response

Tackling antibiotic resistance is a high priority for WHO. A global action plan on antimicrobial resistance, including antibiotic resistance, was endorsed at the World Health Assembly in May 2015. The global action plan aims to ensure prevention and treatment of infectious diseases with safe and effective medicines.

The “Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance” has 5 strategic objectives:

A political declaration endorsed by Heads of State at the United Nations General Assembly in New York in September 2016 signalled the world’s commitment to taking a broad, coordinated approach to address the root causes of antimicrobial resistance across multiple sectors, especially human health, animal health and agriculture. WHO is supporting Member States to develop national action plans on antimicrobial resistance, based on the global action plan.

WHO has been leading multiple initiatives to address antimicrobial resistance:

World Antimicrobial Awareness Week

Held annually since 2015, WAAW is a global campaign that aims to increase awareness of antimicrobial resistance worldwide and to encourage best practices among the general public, health workers and policy makers to avoid the further emergence and spread of drug-resistant infections. Antimicrobials are critical tools in helping to fight diseases in humans, animals and plants. They include antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals and antiprotozoa. WAAW takes place every year from 18 to 24 November. The slogan has previously been, “Antibiotics: Handle with Care” but changed to “Antimicrobials: Handle with Care” in 2020 to reflect the broadening scope of drug resistant infections.

The Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS)

The WHO-supported system supports a standardized approach to the collection, analysis and sharing of data related to antimicrobial resistance at a global level to inform decision-making, drive local, national and regional action.

Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP)

A joint initiative of WHO and Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi), GARDP encourages research and development through public-private partnerships. By 2023, the partnership aims to develop and deliver up to four new treatments, through improvement of existing antibiotics and acceleration of the entry of new antibiotic drugs.

Interagency Coordination Group on Antimicrobial Resistance (IACG)

The United Nations Secretary-General has established IACG to improve coordination between international organizations and to ensure effective global action against this threat to health security. The IACG is co-chaired by the UN Deputy Secretary-General and the Director General of WHO and comprises high level representatives of relevant UN agencies, other international organizations, and individual experts across different sectors.

We know why bacteria become resistant to antibiotics, but how does this actually happen?

Author

Research Fellow in Microbiology, University of Technology Sydney

Disclosure statement

Laura Christine McCaughey receives funding from the Wellcome Trust.

Partners

University of Technology Sydney provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

Antibiotic resistance has the potential to affect everyone. Most people would have heard about antibiotic resistance and studies show many are aware the cause of the current crisis is due to their overuse. But few know how and where the resistance occurs.

A recent study revealed 88% of people think antibiotic resistance occurs when the human body becomes resistant to antibiotics. This isn’t entirely true. The resistance can happen inside our body as it is the host environment for the bacteria; but the important distinction is that the body’s immune system doesn’t change – it’s the bacteria in our bodies that change.

What is antibiotic resistance?

Antibiotic resistance happens when bacteria change in a way that prevents the antibiotic from working. Changes in bacteria, known as resistance mechanisms, come in different forms and can be shared between different bacteria, spreading the problem.

Bacteria and fungi naturally use antibiotics as weapons to kill each other to compete for space and food; they have been doing this for over a billion years. This means they are used to coming into contact with antibiotics in the environment and developing and sharing antibiotic resistance mechanisms.

Most antibiotics we use today are modelled on the ones naturally created by bacteria and fungi. In the past, if the bacteria didn’t encounter the antibiotic they developed resistance for, they could lose the resistance mechanism. But now, because we are overusing antibiotics, the bacteria are encountering them all the time and therefore keeping their resistance mechanisms. Hence the crisis.

Bacteria frequently now encounter antibiotics in the environment (such as the soil) as well as in our bodies and those of animals. Antibiotic resistant bacteria mostly survive these encounters and then multiply in the same manner.

This results in an increased chance of people being infected with antibiotic resistant disease-causing bacteria, which can lead to increased complications, prolonged hospital stays and an increased risk of death.

How resistance develops and spreads

Some bacteria are naturally resistant to certain antibiotics. For instance, the antibiotic vancomycin cannot kill Escherichia coli (E. coli), while metronidazole can’t kill the whooping cough-causing Bordetella pertussis. This is why different antibiotics are prescribed for different infections.

But now, bacteria that could previously be killed by certain antibiotics are becoming resistant to them. This change can occur in two ways:

Genetic mutation is when bacterial DNA, that stores the bacteria’s information and codes for its traits, randomly changes or mutates. If this change, that could be resistance to antibiotics, helps the mutated bacteria survive and reproduce then it will thrive and outgrow the unchanged bacteria.

Random mutation would happen with or without antibiotic overuse. However, the resistant changes only stay in the bacterial population if the antibiotic is constantly present in the bacteria’s environment. Our overuse of antibiotics is resulting in the propagation and maintenance of these changes.

Horizontal gene transfer is when one bacterium acquires antibiotic resistance mechanisms – carried by a particular gene – from other bacteria.

This can occur between the same kinds of bacteria, such as between E. coli that cause urinary tract infections and E. coli that cause food poisoning; or between different kinds of bacteria, such as between E. coli and antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Horizontal gene transfer can also occur between the natural and disease-causing bacteria in our gut. So our gut can act as a source of antibiotic resistance genes.

This is why it is important to only take antibiotics when they are needed. As bacteria can transfer multiple resistance mechanisms at once and can become resistant to many types of antibiotics very quickly – known as multi-drug resistance.

How bacteria block antibiotics from working

There are a number of ways bacteria can resist antibiotics.

2) Efflux pumps – bacteria can use these to pump antibiotics out of themselves before the drugs have had a chance to work. Efflux pumps can be specific to one type of antibiotic or can pump out several different types.

3) Antibiotic degrading enzymes – these molecules are produced by bacteria to degrade antibiotics so they no longer work.

4) Antibiotic altering enzymes – similar to antibiotic degrading enzymes, these molecules change the structure of the antibiotic so it no longer works against the bacteria.

5)Physical changes to antibiotic targets – different antibiotics target different structures inside bacteria. Bacteria are able to change their structures so they still function exactly as they did before but so the antibiotic doesn’t recognise them.

These mechanisms can occur when the bacteria are inside us, inside animals or out in the environment. This is why using antibiotics in the farming industry is such a problem. The bacteria can become antibiotic-resistant in the animals, and then they can pass into the environment through things like manure.

It’s essential we safeguard our current antibiotics by using them appropriately and invest time and money into developing new ones, which we will hopefully not take for granted.

Источники информации:

- http://magazine.medlineplus.gov/article/the-end-of-antibiotics

- http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-to-solve-the-problem-of-antibiotic-resistance/

- http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antibiotic-resistance

- http://theconversation.com/we-know-why-bacteria-become-resistant-to-antibiotics-but-how-does-this-actually-happen-59891