Eat what you kill

Eat what you kill

Eat What You Kill…Except When You Don’t

Proper wildlife management can’t be reduced to simple mantras

By Tyler Freel | Published Nov 18, 2020 4:41 PM

“Eat what you kill,” is a common phrase in hunting media these days. That ideal seems like a very reasonable, honorable principle to live by. Of course, we all enjoy wild game. But sometimes you’ll see a slightly different take on that messaging that goes something like: “If you’re not going to eat it, don’t kill it.” This mantra is frequently used in response to hunting or trapping of animals that aren’t typically considered table-fare, like grizzly bears, wolves, coyotes, and other predators and furbearers.

Here in Alaska, we have a long, controversial history of predator hunting and trapping. And with the gray wolf being delisted in the Lower 48, there are going to be a whole lot more folks (hunters and non-hunters alike) thinking about the ethics of predator hunting and trapping.

Here’s the thing though: It doesn’t matter to a wildlife manager whether you eat your wolves or not (or at least it shouldn’t). The reality is that many of our personal convictions and beliefs about what should be done with game don’t have much teeth when it comes to the big picture of proper wildlife management. We often divide ourselves as an outdoor community, simply because we are unwilling to see past our own bias. Just as hunting is about much more than just the meat to all of us, there are more factors to take into account when we consider things like targeting animals for hides and predator management.

I’m not saying that predator hunters and trappers have an excuse to be intentionally or ignorantly wasteful—only that each of us has a different perspective, and the standards we place on ourselves are usually somewhat arbitrary. Yes, strong moral convictions help hunters be good stewards of the land. But we also need to understand that our way usually isn’t the only way.

For example, let’s say someone who identifies as a “meat hunter” kills a deer in a state that legally requires only the quarters, backstraps, and inner loins to be salvaged from the deer. For the sake of argument, let’s say that hunter also salvages the neck meat, but leaves the ribs in the field because there’s not much meat on them. I think most of us will agree that this hunter has fulfilled his legal and moral obligation for salvaging meat. But now let’s put that same hunter in Alaska, and if he salvages exactly the same meat as in the first case (leaving the rest in the field) he would be guilty of wanton waste according to Alaska law and could be jailed because of the stricter standard. My point? There are different standards and regulations for different situations and locations. At a certain level, almost all of us leave edible parts of animals (tongue, stomach, intestines, head meat, organs, feet) in the woods or on the mountain.

Now let’s look at a wildlife manager’s job. The only real factor of consideration as it pertains to hunters is how many animals of a given species need to be removed or protected in order to propagate a sustainable, balanced ecosystem. An ecosystem must be considered as a whole, and part of that management plan usually involves the active harvest of predators and furbearers, as well as the ungulates that we love to eat. And frankly, the meat, or salvage of any animal parts, has nothing to do with managing that ecosystem.

For example, where I hunt here in Alaska, taking a number of mature grizzly boars in certain areas can have a dramatic positive impact on struggling moose populations. A single bear will sometimes kill upward of 30 or 40 moose calves per year. Even if only the hide and skull is salvaged from that hunter-killed grizz, removing that bear still results in a net gain of available meat—just in the form of moose on the hoof. Removing mature boars also results in the survival of more cubs—that the boar would otherwise have killed—and more available food to support those cubs. You could even make a pretty good argument that nothing is truly wasted by nature; animals that die of old age, starvation, predation, or a hunter’s hand all support life for other organisms.

Although some animals like lynx, beaver, and muskrat can be turned into tasty table-fare, we typically don’t consider most furbearers a suitable food source. Parasites are often cited as a factor, though proper-cooking negates those dangers. We simply find some animals are better to eat than others, and we base our rubric for what needs to be salvaged upon our collective preference. Many of these less-than-tasty species greatly benefit from a regulated harvest.

Also, any fur skinner worth his or her salt invests an incredible amount of time and effort to ensure that the animals are taken cleanly, the pelts are properly handled, and that the yield from that animal is maximized. You could make a good argument that responsible trappers actually put in more work and exercise more care for the perpetuity of the ecosystems they participate in than your average Joe Hunter, who only ventures out occasionally to put a little meat in the freezer.

These points are not intended to diminish the importance of meat to us as hunters. Rather, I’m simply trying to illustrate that conservation in the form of hands-on wildlife management is multi-faceted, and our personal biases can easily keep us from seeing the big picture. If you’re a self-proclaimed “meat hunter,” you’re likely benefiting from the predator management work done by your fellow trappers, predator hunters, and conservation organizations like Delta Waterfowl.

Even the late predator-control-agent-turned-student-of-wolves Frank Glaser noted that, left to its own devices, nature is not maintained in perfect balance so much as it is a never-ending seesaw between abundance and scarcity. Responsible predator control is a key management tool for the stability of many habitats, regardless of whether the predators are eaten by humans or not. The flip-side of this coin is that we also must be willing to restrain ourselves and not hunt any given species when there isn’t a healthy population to support hunter harvest. This is especially true when we are not depending on its meat to sustain communities.

Meat is absolutely one of the best, most tangible things we get out of hunting. Each of us has a responsibility to not only follow the law and salvage what is required, but to go beyond that. Invest the time and effort in the field to care for your meat, keep it clean, and process it yourself if you are able. If you’re hunting or trapping predators or furbearers, learn the craft, target the right animals at the right time to ensure they are prime, use the right equipment to kill them cleanly while minimizing damage, and learn how to handle hides properly. But most importantly, live by a strong set of ethics, but also keep an open mind and respect your fellow hunters’ code of ethics, too.

Tyler Freel is a Staff Writer for Outdoor Life. He lives in Fairbanks, Alaska and has been covering a variety of topics for OL for more than a decade. From backpack sheep hunting adventure stories to DIY tips to gear and gun reviews, he covers it all with a perspective that’s based in experience.

Why Wall Street’s ‘Eat What You Kill’ Motto Is The Only Way To Live

Twitter LinkedIn icon The word «in».

LinkedIn Fliboard icon A stylized letter F.

Flipboard Facebook Icon The letter F.

Email Link icon An image of a chain link. It symobilizes a website link url.

Frank is absolutely right and I congratulate him for recognizing that. I do subtract from the sum total of all human knowledge when I speak. I’m not human. I hunt humans down. I then eat what I kill.

Frank is afraid maybe that I’m trying to take too much of the knowledge he spent 40 or 70 years learning. It’s ok, Frank. You can keep your knowledge. I won’t take it from you. You can go home now.

We’ve become animals in a zoo and wait for our masters to feed us. Our masters are our bosses, the government, the shareholders of massive corporations, the media that spoon feeds us random doses of fear and greed. The banks that squeeze our genitals when we try to break free.

Life only tastes good when you eat what you kill. When you hustle for what you earn and someone pays you money in proportion to the service you’ve offered, the idea you’ve created, your ability to execute on it, and their ability to consume it in a way that benefits them.

Someone asked me the other day “what does it mean when you say you ‘eat what you kill’ “.

It means the greatest pleasure is going into the jungle and mastering the ability to hunt and survive without the help of masters who only pretend to guarantee our safety. Whether you’re an entrepreneur, an employee, a student, a homemaker, a writer, it’s time to start forgetting about all the ways the world has promised you safety and comfort.

Human knowledge has torn apart our families, our bank accounts, and lulled us into a creepy sense of Disney stability. A good friend of mine was just laid off from his job of ten years. He found out through an email and was asked to not come into work for the rest of the week and clean out his desk when security came in on Saturday. All of that human knowledge in an email. Ten years of work. Time to cut costs. “What do I do now?” he asked me.

How to Eat What You Kill:

— Don’t depend on one boss, buyer for your company, product, service you offer, etc. Diversify everything you can. When I was starting Stockpickr I was trying to start 9 other companies simultaneously plus was running a fund of hedge funds. When I was trying to sell Stockpickr, I was in serious talks with 5 other companies. When I write articles, there’s 5 different sites I write for. When I was broke and about to lose my home, I wrote to over 100 different people to try to build up my network. When I worked at HBO I tried to build value in every department, all the time I was preparing my exit by planning out my first successful startup.

— Become an expert. Read every book, blog, website, whatever, about what you want to be an expert in. When I began daytrading for hedge funds I must have read over 100 books on trading and investing and then wrote over 1000 programs testing out different trading models. And I still sucked at trading. I then spent years doing it before I felt I was halfway decent enough to pull consistent money out. And only then hedge funds started hiring me.

— Connect people. If you introduce person A to person B and then person B is able to solve a pain point in his life, then you just made a good connection. Each connection is another string in the tightly woven net you build that will catch you when you fall and throw you to higher heights than you’ve ever experienced before. And you will fall. Don’t think it can’t happen.

— Give ideas for free. If you have no network yet then you have to build it. Nobody wants to help you for free. They are all just trying to survive. Even billionaires are trying to protect their luxury-soaked lifestyles plagued by jealousies and oversexed libidos. You have to build your idea muscle and work hard to come up with ideas that can really help these people. Then send them the ideas for free. Not everyone will respond, but the benefits are:

— Always work on your exit. No matter where you are: a job, a startup, your startup, writing a column, working at Mcdonalds, always diversify your possible exits and begin immediately working on them. You don’t have to exit tomorrow, but never forget that you can get that email tomorrow that says you have to clean out your desk by Saturday. Build your personal brand, make your boss’s contacts your contacts, make calls, send emails, leave responses on blogs, come up with ideas out of the scope of your job description

— Never say a bad word about anyone. Don’t betray anyone. Don’t backstab anyone or step on anyone’s toes. Don’t gossip.This might come into conflict with the idea of “eating what you kill” but backstabbing in order to do it implies you have a “scarcity” mentality. That there isn’t enough out there unless you kill someone else in order to get what you want. Let me tell you something: there’s enough out there for you and me. Your competition is not other people but the time you kill, the ill will you create, the knowledge you neglect to learn, the connections you fail to build, the health you sacrifice along the path, your inability to generate ideas, the people around you who don’t support and love your efforts, and whatever god you curse for your bad luck. Avoid those and you avoid competition. Don’t hurt anyone.

— Don’t care what people think. People will hate you for being a hunter: your bosses, colleagues, partners, investors, extended family. But they don’t have to feed your family. You do. This is how you do it. Once you care what others think, you’ve lost. Then you’ve just set up the same boundaries for yourself that those other people have set up for themselves. They are all smaller than you and live in straitjackets. It’s easy to kill someone in a straitjacket. Don’t be one of those people.

— Create your luck. Luck doesn’t come from god or come magically out of the air. When a runner wins a race by a one-tenth of a second chances are he prepared more, he studied his competition, his diet was that much better, he was better rested, he was mentally fit, etc. Once you’ve checked all the boxes on your preparation, guess what, you’ll be lucky. A lot of people say, for instance, that Mark Cuban became a billionaire by luck. I address that in this post.

— Reward is unrelated to risk. People say, “no risk, no reward.” This is not true. I don’t like to take risks. I have a family to feed. Don’t take risks with your kids. Diversification is not about diversifying your cash investments, it’s about diversifying all the sources of plenty in your life: opportunities, knowledge, friends, networks, investments, risks, health (physical, emotional, mental, spiritual, i.e. the Daily Practice I recommend). To eat what you kill, minimize risk so you don’t die on the hunt. You do that by diversifying every part of your life. The outcome of this is that if you forgot to bring your knife on the hunt, you still have your gun. If you forgot to bring your ideas full force into the game, you still have your network, if you lose on one risk, you still have the nine others. That’s where you get the reward.

— Take responsibility for all failures. It’s your fault when you go hungry. Former world chess champion Mikhail Botvinnik said in his book, “100 selected games” that the only way to reach the highest level of success is to develop the ability to critique your own failures. Note the word, “ONLY” in this. Anecdote: Botvinnik used to train by playing against someone who would blow smoke in his face so as to get accustomed to difficult playing situations. He was the world chess champion for 15 years.

(Botvinnik versus future world champion Bobby Fischer in 1962)

— Honesty. If you don’t ask for what you want, chances are you won’t get it. If you don’t say what you believe, you’ll never stand out from the 99% of people out there who hide the truth about themselves and their desires. If you don’t stand up and say or show how special you are, nobody will ever think you are special. Nobody is out there advocating for you. Honesty about what you feel, believe, know, think, want, will make you a multi-dimensional being in a flatland world.

— Patience. Most important. A three year old could be honest but it doesn’t mean anything. They still shit in their pants on occasion. You need to grow up. To check all of the boxes on the above items. To do the Daily Practice to stay in mental, physical, emotional, spiritual shape. Toavoid crappy people, to be honest, to take responsibility, and so on. Being a hunter is very discouraging. Sometimes you have to go for stretches of disappointment where there’s nothing to kill and then nothing to eat. To be honest, I’m on a four year stretch. I’m hunting for my next kill and I will get it. During those times its most difficult to keep balanced and stay sane. I’ve talked many people off ledges during these periods, including myself. It’s these times it’s most important to only be around the people who love you, and avoid the damaging people who will bring you to their peculiar and particular circles of hell. You don’t want to go to hell. At the end of the day, patience is the virtue that takes you to heaven.

Don’t worry about adding or subtracting to the sum of human knowledge. Human knowledge is never that great. Be better than human.

Eat What You Kill without Starvation!

Jetty 9 introduced the Eat-What-You-Kill [1] The EatWhatYouKill strategy is named after a hunting proverb in the sense that one should only kill to eat. The use of this phrase is not an endorsement of hunting nor killing of wildlife for food or … Continue reading execution strategy to apply mechanically sympathetic techniques to the scheduling of threads in the producer-consumer pattern that are used for core capabilities in the server. The initial implementations proved vulnerable to thread starvation and Jetty-9.3 introduced dual scheduling strategies to keep the server running, which in turn suffered from lock contention on machines with more than 16 cores. The Jetty-9.4 release now contains the latest incarnation of the Eat-What-You-Kill scheduling strategy which provides mechanical sympathy without the risk of thread starvation in a single strategy. This blog is an update of the original post with the latest refinements.

Parallel Mechanical Sympathy

Parallel computing is a “false friend” for many web applications. The textbooks will tell you that parallelism is about decomposing large tasks into smaller ones that can be executed simultaneously by different computing engines to complete the task faster. While this is true, the issue is that for web application containers there is not an agreement on what is the “large task” that needs to be decomposed.

From the applications point of view the large task to be solved is how to render a complex page for a user, combining multiple requests and resources, using many services for authentication and perhaps RESTful access to a data model on multiple back end servers. For the application, parallelism can improve quality of service of rendering a single page by spreading the decomposed tasks over all the available CPUs of the server.

However, a web application container has a different large task to solve: how to provide service to hundreds or thousands, maybe even hundreds of thousands of simultaneous users. Unfortunately, for the container, the way to optimally allocate its this decomposed task to CPUs is completely opposite to how the application would like it’s decomposed tasks to be executed.

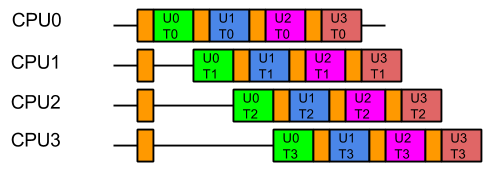

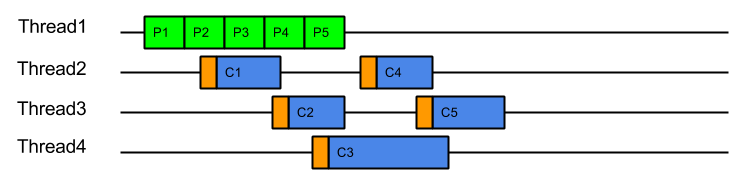

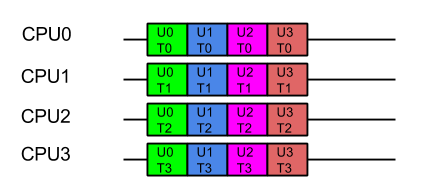

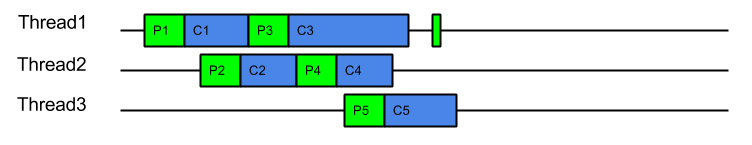

Consider a server with 4 CPUs serving 4 users each which each have 4 tasks. The applications ideal view of parallel decomposition looks like:

This view suggests that each user’s combined task will be executed in minimum time. However some users must wait for prior users tasks to complete before their execution can start, so average latency is higher.

Furthermore, we know from Mechanical Sympathy that such ideal execution is rarely possible, especially if there is data shared between tasks. Each CPU needs time to load its cache and register with data before it can be acted on. If that data is specific to the problem each user is trying to solve, then the real view of the parallel execution looks more like the following, the orange blocks indicating the time taken to load the CPU cache with user and task related data:

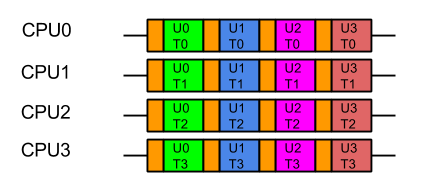

So from the containers point of view, the last thing it wants is the data from one users large problem spread over all its CPUs, because that means that when it executes the next task, it will have a cold cache and it must be reloaded with the data of the next user. Furthermore, executing tasks for the same user on different CPUs risks Parallel Slowdown, where the cost of mutual exclusion, synchronisation and communication between CPUs can increase the total time needed to execute the tasks to more than serial execution. If the tasks are fully mutually excluded on user data (unlikely but a bounding case), then the execution could look like:

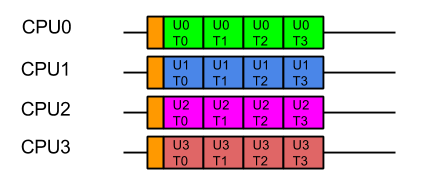

For optimal execution from the containers point of view it is far better if tasks from each user, which use common data, are kept on the same CPU so the cache only needs to be loaded once and there is no mutual exclusion on user data:

While this style of execution does not achieve the minimal latency and throughput of the idealised application view, in reality it is the fairest and most optimal execution, with all users receiving similar quality of service and the optimal average latency.

In summary, when scheduling the execution of parallel tasks, it is best to keep tasks that share data on the same CPU so that they may benefit from a hot cache (the original blog contains some micro benchmark results that quantifies the benefit).

Produce Consume (PC)

In order to facilitate the decomposition of large problems into smaller ones, the Jetty container uses the Producer-Consumer pattern:

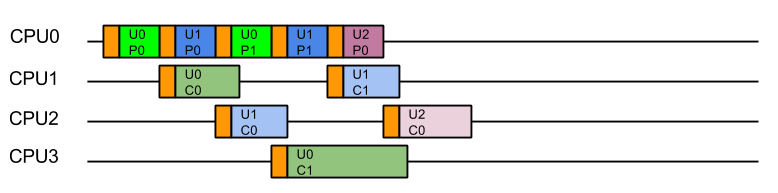

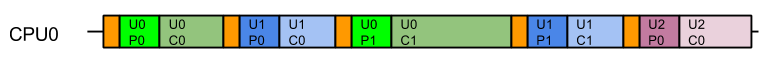

The producer-consumer pattern adds another way that tasks can be related by data. Not only might they be for the same user, but consuming a task will share the data that results from producing the task. A simple implementation can achieve this by using only a single CPU to both produce and consume the tasks:

The resulting execution pattern has good mechanical sympathy characteristics:

Here all the produced tasks are immediately consumed on the same CPU with a hot cache! Cache load times are minimised, but the cost is that server will suffer from Head of Line (HOL) Blocking, where the serial execution of task from a queue means that execution of tasks are forced to wait for the completion of unrelated tasks. In this case tasks for U1C0 need not wait for U0C0 and U2C0 tasks need not wait for U1C1 or U0C1 etc. There is no parallel execution and thus this is not an optimal usage of the server resources.

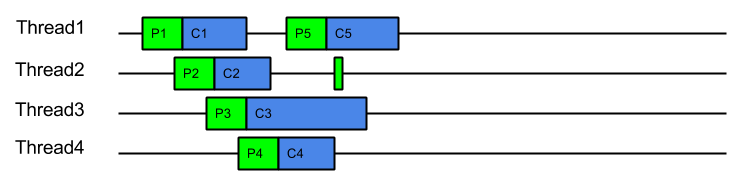

Produce Execute Consume (PEC)

To solve the HOL blocking problem, multiple CPUs must be used so that produced tasks can be executed in parallel and even if one is slow or blocks, the other CPU can progress the other tasks. To achieve this, a typical solution is to have one Thread executing on a CPU that will only produce tasks, which are then placed in a queue of tasks to be executed by Threads running on other CPUs. Typically the task queue is abstracted into an Executor:

This strategy could be considered the canonical solution to the producer consumer problem, where producers are separated from consumers by a queue and is at the heart of architectures such as SEDA. This strategy well solves the head of line blocking issue, since all tasks produced can complete independently in different Threads on different CPUs:

This represents a good improvement in throughput and average latency over the simple Produce Consume, solution, but the cost is that every consumed task is executed on a different Thread (and thus likely a different CPU) from the one that produced the task. While this may appear like a small cost for avoiding HOL blocking, our experience is that CPU cache misses significantly reduced the performance of early Jetty 9 releases.

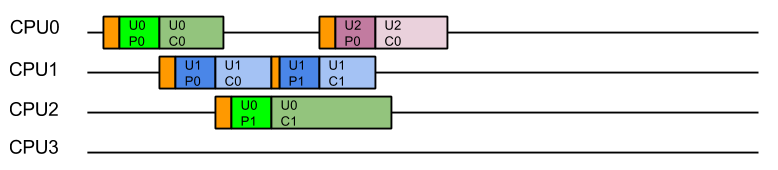

Eat What You Kill (EWYK) AKA Execute Produce Consume (EPC)

The result is that a task is consumed by the same Thread, and thus likely the same CPU, that produced it, so that consumption is always done with a hot cache:

Moreover, because any thread that completes consuming a task will immediately attempt to produce another task, there is the possibility of a single Thread/CPU executing multiple produce/consume cycles for the same user. The result is improved average latency and reduced total CPU time.

Starvation!

Unfortunately, a pure implementation of EWYK suffers from a fatal flaw! Since any thread producing a task will go on to consume that task, it is possible for all threads/CPU to be consuming at once. This was initially seen as a feature as it exerted good back pressure on the network as a busy server used all its resources consuming existing tasks rather than producing new tasks. However, in an application server consuming a task may be a blocking process that waits for more data/frames to be produced. Unfortunately if every thread/CPU ends up consuming such a blocking task, then there are no threads left available to produce the tasks to unblock them. Dead lock!

A real example of this occurred with HTTP/2, when every Thread from the pool was blocked in a HTTP/2 request because it had used up its flow control window. The windows can be expanded by flow control frames from the other end, but there were no threads available to process the flow control frames!

Thus the EWYK execution strategy used in Jetty is now adaptive and it can can use the most appropriate of the three strategies outlined above, ensuring there is always at least one thread/CPU producing so that starvation does not occur. To be adaptive, Jetty uses two mechanisms:

Thus the simple produce consume (PC) model is used for non-blocking tasks; for blocking tasks the EWYK, aka Execute Produce Consume (EPC) mode is used if a reserved thread is available, otherwise the SEDA style Produce Execute Consume (PEC) model is used.

The adaptive EWYK strategy can be written as :

Chained Execution Strategies

As stated above, in the Jetty use-case it is common for the execution strategy used by the IO layer to call tasks that are themselves an execution strategy for producing and consuming HTTP/2 frames. Thus EWYK strategies can be chained and by knowing some information about the mode in which the prior strategy has executed them the strategies can be even more adaptive.

The adaptable chainable EWYK strategy is outlined here:

An example of how the chaining works is that the HTTP/2 task declares itself as invocable EITHER in blocking on non blocking mode. If IO strategy is operating in PEC mode, then the HTTP/2 task is in its own thread and free to block, so it can itself use EWYK and potentially execute a blocking task that it produced.

However, if the IO strategy has no reserved threads it cannot risk queuing an important Flow Control frame in a job queue. Instead it can execute the HTTP/2 as a non blocking task in the PC mode. So even if the last available thread was running the IO strategy, it can use PC mode to execute HTTP/2 tasks in non blocking mode. The HTTP/2 strategy is then always able to handle flow control frames as they are non-blocking tasks run as PC and all other frames that may block are queued with PEC.

Conclusion

The EWYK execution strategy has been implemented in Jetty to improve performance through mechanical sympathy, whilst avoiding the issues of Head of Line blocking, Thread Starvation and Parallel Slowdown. The team at Webtide continue to work with our clients and users to analyse and innovate better solutions to serve high performance real world applications.

Eat What You Kill

A producer consumer pattern for Jetty HTTP/2 with mechanical sympathy

The problem

The problem we are trying to solve is the producer consumer pattern, where one process produces tasks that need to be run to be consumed. This is a common pattern with two key examples in the Jetty Server:

For the purposes of this blog, we will consider the problem in general, with the producer represented by following interface:

The optimisation task that we trying to solve is how to handle potentially many producers, each producing many tasks to run, and how to run the tasks that they produce so that they are consumed in a timely and efficient manner.

Produce Consume

The simplest solution to this pattern is to iteratively produce and consume as follows:

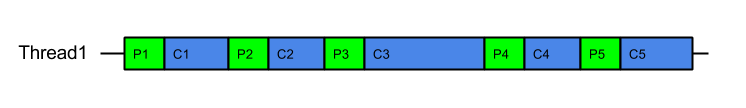

This strategy iteratively produces and consumes tasks in a single thread per Producer:

Produce Execute Consume

To solve the HOL blocking problem, multiple threads must be used so that produced tasks can be executed in parallel and even if one is slow or blocks, the other threads can progress the other tasks. The simplest application of threading is to place every task that is produced onto a queue to be consumed by an Executor:

This strategy could be considered the canonical solution to the producer consumer problem, where producers are separated from consumers by a queue and is at the heart of architectures such as SEDA. This strategy solves well the head of line blocking issue, since all tasks produced can complete independently in different threads (or cached threads):

However, while it solves the HOL blocking issue, it introduces a number of other significant issues:

Thus the ProduceExecuteConsume strategy has solved the HOL blocking concern but at the expense of very poor performance on both latency (dispatch times) and execution (cold caches), as well as introducing concerns of contention and back pressure. Many of these additional concerns involve the concept of Mechanical Sympathy, where the underlying mechanical design (i.e. CPU cores and caches) must be considered when designing scalable software.

How Bad Is It?

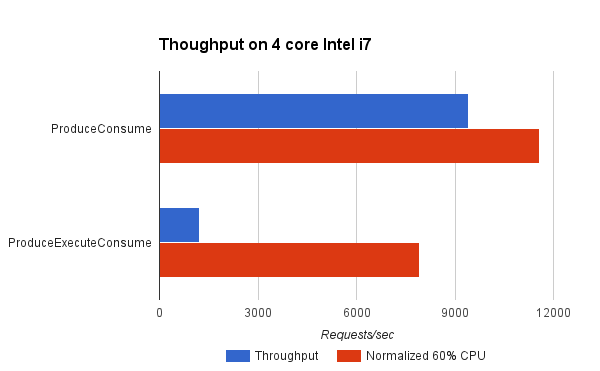

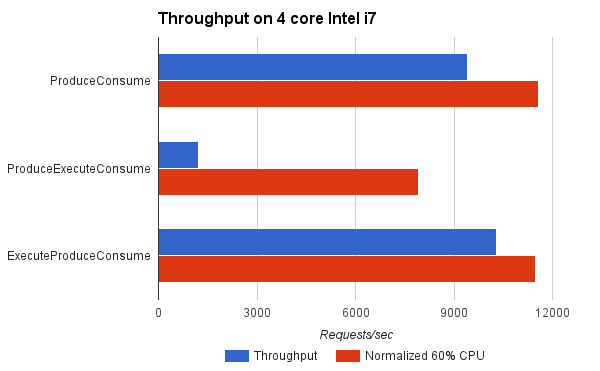

Pretty Bad! We have written a benchmark project that compares the Produce Consume and Produce Execute Consume strategies (both described above). The Test Connection used simulates a typical HTTP request handling load where the production of the task equates to parsing the request and created the request object and the consumption of the task equates to handling the request and generating a response.

It can be seen that the ProduceConsume strategy achieves almost 8 times the throughput of the ProduceExecuteConsume strategy. However in doing so, the ProduceExecuteConsume strategy is using a lot less CPU (probably because it is idle during the dispatch delays). Yet even when the throughput is normalised to what might be achieved if 60% of the available CPU was used, then this strategy reduces throughput by 30%! This is most probably due to the processing inefficiencies of cold caches and contention between tasks in the ProduceExecuteConsume strategy. This clearly shows that to avoid HOL blocking, the ProduceExecuteConsume strategy is giving up significant throughput when you consider either achieved or theoretical measures.

What Can Be Done?

Consideration of the SEDA architecture led to the development of the Disruptor pattern, which self describes as a “High performance alternative to bounded queues for exchanging data between concurrent threads”. This pattern attacks the problem by replacing the queue between producer and consumer with a better data structure that can greatly improve the handing off of tasks between threads by considering the mechanical sympathetic concerns that affect the queue data structure itself.

While replacing the queue with a better mechanism may well greatly improve performance, our analysis was that it in Jetty it was the parallel slowdown of sharing the task data between threads that dominated any issues with the queue mechanism itself. Furthermore, the problem domain of a full SEDA-like architecture, whilst similar to the Jetty use-cases is not similar enough to take advantage of some of the more advanced semantics available with the disruptor.

Even with the most efficient queue replacement, the Jetty use-cases will suffer from some dispatch latency and parallel slow down from cold caches and contending related tasks.

Another technique for avoiding parallel slowdown is a Work Stealing scheduling strategy:

In a work stealing scheduler, each processor in a computer system has a queue of work items to perform…. New items are initially put on the queue of the processor executing the work item. When a processor runs out of work, it looks at the queues of other processors and “steals” their work items.

This concept initially looked very promising as it appear that it would allow related tasks to stay on the same CPU core and avoid the parallel slowdown issues described above.

It would require the single task queue to be broken up in to multiple queues, but there are suitable candidates for finer granularity queues available (e.g. the connection).

Unfortunately, several efforts to implement it within Jetty failed to find an elegant solution because it is not generally possible to stick a queue or thread to a processor and the interaction of task queues vs thread pool queues added an additional level of complexity. More over, because the approach still involves queues it does not solve the back pressure issues and the execution of tasks in a queue may flush the cache between production and consumption.

However consideration of the principles of Work Stealing inspired the creation of a new scheduling strategy that attempt to achieve the same result but without any queues.

Eat What You Kill!

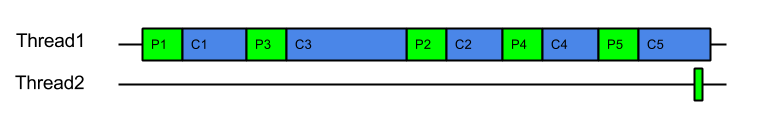

This strategy can still operate like ProduceConsume using a loop to produce and consume tasks with a hot cache. A dispatch is performed to recruit a new thread to produce and consume, but on a busy server where the delay in dispatching a new thread may be large, the extra thread may arrive after all the work is done. Thus the extreme case on a busy server is that this strategy can behave like ProduceConsume with an extra noop dispatch:

Serial queueless execution like this is optimal for a servers throughput: There is not queue of produced tasks wasting memory, as tasks are only produced when needed; tasks are always consumed with hot caches immediately after production. Ideally each core and/or thread in a server is serially executing related tasks in this pattern… unless of course one tasks takes too long to execute and we need to avoid HOL blocking.

EatWhatYouKill avoids HOL blocking as it is able to recruit additional threads to iterate on production and consumption if the server is less busy and the dispatch delay is less than the time needed to consume a task. In such cases, a new threads will be recruited to assist with producing and consuming, but each thread will consume what they produced using a hot cache and tasks can complete out of order:

An alternate way to visualise this strategy is to consider it like ProduceConsume, but that it dispatches extra threads to work steal production and consumption. These work stealing threads will only manage to steal work if the server is has spare capacity and the consumption of a task is risking HOL blocking.

This strategy has many benefits:

For the benchmark, ExecuteProduceConsume achieved better throughput than ProduceConsume because it was able to use more CPU cores when appropriate. When normalised for CPU load, it achieved near identical results to ProduceConsume, which is to be expected since both consume tasks with hot caches and ExecuteProduceConsume only incurs in dispatch costs when they are productive.

This indicates that you can kill your cake and eat it too! The same efficiency of ProduceConsume can be achieved with the same HOL blocking prevention of ProduceExecuteConsume.

Conclusion

The EatWhatYouKill (aka ExecuteProduceConsume) strategy has been integrated into Jetty-9.3 for both NIO selection and HTTP/2 request handling. This makes it possible for the following sequence of events to occur within a single thread of execution:

This allows a single thread with hot cache to handle a request from I/O selection, through frame parsing to response generation with no queues or dispatch delays. This offers maximum efficiency of handling while avoiding the unacceptable HOL blocking.

Early indications are that Jetty-9.3 is indeed demonstrating a significant step forward in both low latency and high throughput. This site has been running on EWYK Jetty-9.3 for some months. We are confident that with this new execution strategy, Jetty will provide the most performant and scalable HTTP/2 implementation available in Java.

A cold business truth: you only eat what you kill

The old saying “you only eat what you kill” applies to business, no matter how grotesque… are you prepared for the reality of it all?

You eat what you kill

How many times, as brokers have you heard this before? But have you ever really stopped to think about what it means? Obviously, it is a hunting metaphor, but when applied to your brokerage business, it could mean that getting it or not is the difference between eating and survival or starving to death.

The problem is that you can’t go hunting (or killing, as some like to call it) without first having a hunter’s training course, but even that doesn’t teach you how to hunt, only how to not shoot yourself or others – in the real estate world, think of this as your licensing course. But still, you will starve to death. So let’s blow this thing up and get right down to the details.

1. Trapping

Trapping is in fact not hunting, however, the result is still hopefully the same. In business, we set traps all day. Some are more successful than others. Like marketing, where you are trying to lure the business in through any various means, video, flyers, radio adds, etc., you’re baiting the trap.

2. Hunting

Hunting is a skill game. This is where you have trained to use your tools extensively and you are sitting by, patiently, all wide eyed, up early, waiting for anything to move in front of you.

3. Stalking

This is not hunting. This is where you have identified the business, you know the point of contact, and may have even studied the weakness of the operation. You don’t wait around. You intend on not returning unless the business is with you.

4. Fishing

Ok really who cares about fishing? Fishermen. Fishing is kind of like referrals where it takes a lot of previous years of experience before anyone wants to go with you.

The takeaway

What this means is that in order to “eat what you kill” or get paid only on the business you go after and close is you first go to know how. Determine what type of hunting it is that you do best and then slowly add in all the other components. I can tell you that all the old timers that I know both in hunting and in business know how and use a combination of all four.

With 16 years of industry experience, earning his CCIM designation in 2007, Smith has held various leadership positions from CCIM Chapter President, CCIM Institute Regional VP, to Partner at McFalls & Smith International Development. Today, Smith is a commercial sales expert at Prudential PenFed Realty’s Commercial Division, an Advisory Board Member at the University of Baltimore’s Merrick School of Business, and a Professor at the Professional Development Institute. Smith has educated hundreds of REALTORS, investors, and small business owners, helping them find success through Commercial Real Estate.

Leave a Reply

AdBlocker Message

The

American Genius

news neatly in your inbox

Subscribe to our mailing list for news sent straight to your email inbox.

Thank you for subscribing.

Something went wrong.

we respect your privacy and take protecting it seriously