In what century was the norman invasion on the british isles ответ

In what century was the norman invasion on the british isles ответ

The Norman Conquest of England / Нормандское завоевание Англии

The Norman Conquest was the fifth invasion. And it is so well-known because it was the last invasion of Britain.

In the 11th century the Normans came to England from Normandy. They were Norsemen who had already settled in the northern part of France. This means that the Normans adopted the French language, French manners, customs and way of life, because they lived among French people.

On October 14th, 1066, King William (Duke of Normandy) defeated the army of the English King Harold in the Battle of Hastings.

No matter how hard the people of England tried to defend their country, the Normans were still much stronger than the Anglo-Saxons.

The Normans made many poor English people their own serfs. Besides this they burnt their houses and killed them.

When William, Duke of Normandy, was crowned, he became the King of England. He settled in London and was called William the Conqueror.

For 500 years the Normans were masters of Britain.

A great number of important changes are connected with the Normans. They brought with them Latin and French civilizations, the laws and the organization of the land. Many Latin and French words penetrated into the Old English language. Commerce and trade grew very quickly, but the population grew even faster.

London became a busy, rich and crowded city. The Normans did their best to make it look beautiful.

At that time the Tower of London was built on the Thames and it stands there still unchanged.

Westminster Abbey was finished and William was the first King to be crowned there. Since then all English kings were crowned in Westminster Abbey.

► Читайте также другие темы раздела «Some historical facts about Great Britain / Некоторые исторические факты о Великобритании»:

Norman Conquest of England

Definition

The Norman Conquest of England (1066-71) was led by William the Conqueror who defeated King Harold II at the Battle of Hastings. The Anglo-Saxon elite lost power as William redistributed land to his fellow Normans. Crowned William I of England (r. 1066-1087) on Christmas Day, the new order would take five years to fully control England.

Following Harold’s death at Hastings, William was obliged to see off several major invasions and rebellions, but once established, Norman England would witness profound changes in all areas of society. These changes included a restructuring of the Church, innovations in military and religious architecture, the evolution of the English language, the spread of feudalism and a much greater contact with continental Europe, especially France.

Advertisement

The Claims On the English Crown

In 1066 when the Norman invasion began, the king of England was Harold II, formerly Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex. Harold had hardly had time to warm his throne, crowned as he was on 6 January 1066 but it would soon prove to be one of the most hotly contested thrones in medieval Europe. Two other men considered themselves the rightful king of England, and both were highly dangerous and experienced military leaders.

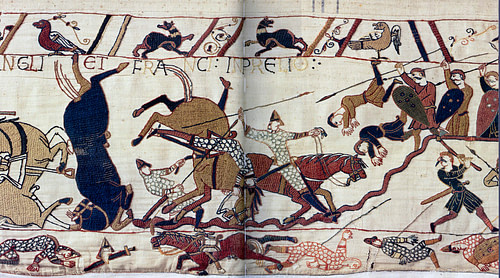

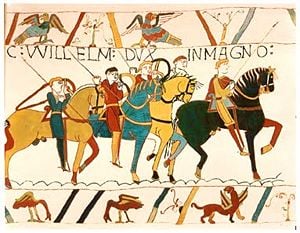

William, Duke of Normandy (r. from 1035), centred his claim on his relationship with Harold’s predecessor, Edward the Confessor (r. 1042-1066) who was a distant relation (Count Richard I of Normandy was Edward’s grandfather and William’s great-grandfather). William also claimed that the English king, without children of his own, had once promised the Norman he would be Edward’s successor. As it turned out, on his deathbed Edward selected the Anglo-Saxon Harold, a member of the enormously powerful Godwine family and then the foremost military commander in England, as the official heir. The Normans also claimed that Harold had visited Normandy in 1064, where he had been captured by the Count Guy of Ponthieu and then handed over to William. A condition of Harold’s release, so the Norman version of the story goes (and additionally captured in the Bayeux Tapestry), was that the Earl of Wessex promised to become William’s vassal and prepare the way for an invasion. Thus, William felt wronged and was fully prepared to enforce his claim with a full-scale military invasion of England.

Advertisement

Such was the scale of William’s preparations in the summer of 1066, Harold knew full well what was coming and he gathered an army to await the Norman’s dreaded arrival. Unfortunately for Harold, time passed without the invaders turning up and he was forced to stand down his army. Even worse, the third claimant to the English throne then chose his moment to enter the complex political drama.

Harald Hardrada was the king of Norway (aka Harold III, r. 1046-1066) and he had two dubious points to his claim: first, he believed he was also the rightful ruler of Denmark, a kingdom which had long-claimed sovereignty over large parts of England and, second, his predecessor, Sweyn (Swein) of Norway had been the illegitimate son of Aelfgifu, wife of King Cnut (aka Canute), the king of England from 1016 to 1035. Like William, Hardrada was prepared to press his claim through force, and he amassed an invasion fleet which sailed to England in September 1066. Harold faced the impossible situation of two invasions in the opposite parts of his kingdom at exactly the same time; at the very least, 1066 was going to be very eventful indeed.

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

Battle of Hastings

Hardrada’s invasion was initially successful against an Anglo-Saxon army, led by two inexperienced English earls, at the Battle of Fulford Gate near York on 20 September. Then Harold marched a second army northwards and won a decisive victory at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, also near York, five days later, in which Hardrada was killed along with his ally, Harold’s traitorous brother Tostig. Next, on 28 September, William and his invasion army landed at Pevensey in Sussex, southern England. Harold had little option but to march back to the south and do battle for a second time, speed being of the essence as the Normans had already begun torching pockets of south-east England.

Harold arrived in London on 6 October and mustered what forces he could, a mixture of the army from Stamford Bridge and a local levy (fyrd) of less well-trained troops from the shires. The two armies, likely numbering around 5,000 men each, faced off at Hastings on 14 October. The Anglo-Saxon army was largely composed of infantry, with the elite being the king’s housecarls (huscarls) who wore chain armour and wielded huge axes. The Normans and their French allies, in contrast, had a significant number of archers, probably a unit of crossbowmen, and at least 1,000 cavalry.

Advertisement

Initially, when Harold occupied a small rise known as ‘hammer-head ridge’, the English resisted well the early Norman attacks, thanks to their strategy of protecting each other with their shields. When discipline broke amongst the Anglo-Saxons, though, and warriors moved down the hill in pursuit of a (perhaps feigned) Norman cavalry retreat, the battle swung in William’s favour. Eventually, the cavalry was successful in breaking up the Anglo-Saxon ‘shield-wall’ formation and, when Harold and his two brothers were killed, William’s victory was assured. The English king, at least according to tradition, was felled by an arrow to his eye, and then he was hacked to pieces as he lay prone on the ground. It was a great victory for William, who rested his men and then prepared to continue his invasion by subduing the south-east of England and taking London.

William’s March on London

The great city of London was one of William’s priorities but it was protected both by the River Thames from the south and by the fact the only crossing point was an easily defended fortified bridge. Consequently, the Norman duke decided on a much less direct attack. In effect, William performed a gigantic loop around south-east England and so was ultimately in a position to cut off the roads leading to London and attack the city from the north in November 1066. En route, reinforcements landed from Normandy and the important towns and fortifications of Romney, Dover, Winchester, and Canterbury were all taken. In the event, William’s successes elsewhere and the lack of a significant army after the loss at Hastings saw the remaining Anglo-Saxon nobles and their figurehead Edgar Ætheling, great-nephew of Edward the Confessor (r. 1042-1066), surrender the city and the kingdom without a fight.

The victorious Norman duke was crowned William I of England on Christmas Day 1066 in Westminster Abbey, bringing an end to 500 years of Anglo-Saxon rule. Motte and bailey castles were built everywhere, and Norman lords took over estates across the conquered territory. William now sought to focus on the northern half England and subdue the lingering Anglo-Saxon rebels there, which included Eadwine, the earl of Mercia, and Morcar, the earl of Northumbria (both of whom had deserted London in its hour of need). 1066 had been spectacularly successful for the Normans but William now faced five years of on-off fighting to fully secure all the parts of his kingdom.

Advertisement

Rebellions, Invasions & the Harrying of the North

In the summer of 1067 the first of a long line of threats appeared on the horizon. This first danger came from an unusual quarter, too, in the form of Eustace of Boulogne, one of William’s former allies, who attacked Dover with a fleet from northern France. Just after this attack was repelled, another threat came at Exeter where a major rebellion had broken out, largely motivated by William’s new burdensome taxes. The king marched there personally and lay siege to the city for 18 days until it capitulated in January 1068. By the spring, William felt secure enough to invite his wife Mathilda over from Normandy and have her crowned the queen of England in Westminster Abbey on 11 May.

Far from being over, though, a new danger came in the form of Godwine, son of Harold II, then in self-imposed exile in Ireland. Godwine assembled a fleet of rebels and pirates and landed on the western coast of England at Avonmouth in the summer of 1068. Bristol was the target, but the city resisted, and a local shire army was mustered, which successfully saw off the attack and forced Godwine to return to Ireland.

At the same time as this failed Godwinson fightback, a rebellion broke out in York. The key city of the north, and indeed the entire region, had always been difficult to rule by kings based far to the south. William again responded emphatically, marching northwards, all the time razing any rebellious villages and towns he came across and building castles, notably at Warwick and Nottingham. The rebels at York were rallying around their figurehead of Edgar Ætheling who had been benefitting from both the sanctuary and active support of the king of the Scots, Malcolm III (r. 1058-1093) who had married Edgar’s sister Margaret. The rebels wanted the lands back which many had lost since Hastings, and they wanted Edgar as their king. Fortunately for William, his army had been so ruthless during its march northwards that by the time the Normans arrived at York, the city decided it was better to surrender. William had a castle built, a garrison installed and hostages were taken, all to ensure the city did not forget who the rightful king was.

Advertisement

The peace did not last long, and in January 1069, both Durham and York were sacked by rebel armies. Once again, William marched north and this time routed the rebels in battle. Not able to rest on his laurels, a few months later William faced yet another foreign threat, this time in the guise of King Sweyn II of Denmark (r. 1047-1076). Sweyn sent his brother, Asbjorn and 300 ships to attack the northeast coast of England to see what they could plunder from the unsettled kingdom. There these Viking warriors teamed up with Anglo-Saxon rebels and sacked York. For a third time, William marched north to the city, but by the time he got there the rebels had fled and the Danes had sailed off down the River Trent. In age-old fashion, the king paid the Vikings to go home, and as a clear statement of his intent to rule the whole of England, William spent Christmas 1069 at York.

The Ely Rebellion & Completion of the Conquest

King Sweyn of Denmark arrived in person on English shores in 1070. The force led by his brother the previous year had never left England as they had promised William to do but the harsh winter and lack of foraging possibilities had depleted their numbers significantly. Otherwise, Sweyn may have planned to launch a full-scale invasion of England. Instead, the Danes linked up with Anglo-Saxon rebels who had been gathering under the local noble Hereward the Wake in East Anglia. Hereward had lost his family’s lands following the conquest, and these allies of mutual mischief attacked Peterborough in the summer of 1070, looting the monastery there. Unfortunately for Hereward, the Danes then sailed off home with this treasure and left him alone to face William’s wrath. Despite the setback, the rebel leader continued his guerrilla warfare with some success, and he gradually attracted more followers from across the country, including Earl Morcar.

After several small expeditions failed to break through the difficult terrain of the fens of East Anglia, William was obliged to lead an army there in person. Methodical as ever, in the summer of 1071 the king mobilised by both land and sea, eventually building a causeway which allowed him to transport the siege engines with which he could attack Ely Abbey, now the rebel headquarters. After fortifications were built around the abbey and seeing William’s determination at close quarters, the rebels either surrendered or fled. William had put down the last Anglo-Saxon rebellion to threaten his reign. Then, in 1072, Scotland was attacked to stop the regular raids on Northumbria, and when Malcolm III sued for peace, part of the deal saw Edgar Ætheling exiled to Flanders. A new chapter of English history was already underway: the Normans were here to stay.

Impact of the Conquest

Besides the terrible deaths, widespread destruction, and appearance of castles everywhere, there were many other consequences to the Norman conquest in England and abroad. The most immediate impact was seen in the almost total replacement of the Anglo-Saxon ruling and landowning elite by a much smaller number of Normans, all given estates and titles by William. This dramatic changeover of ownership is starkly revealed in William’s 1086-7 Domesday Book. A knock-on effect of this policy was the further development of the system of feudalism, that is the giving of lands (fiefs) to a lord (vassal) who promised his king military service (either in person or by paying knights or both). With this policy, the system of manorialism also evolved to become much more widespread. That is free and unfree (serf or villein) labour was used to work the land for the owner’s profit.

The Church elite did not escape notice either, with almost all bishops being replaced by Norman ones, diocese headquarters were often moved to urban centres, and new stone cathedrals in the Norman-Romanesque style of architecture were built such as at Winchester, York, and Canterbury.

Although there was no great population movement from Normandy to England, ordinary people would have witnessed first hand this changeover of the elite, even if some Anglo-Saxon tools of governance like sheriffs did continue (although the offices themselves went to Normans). French was heard everywhere, and the language had a lasting influence on English syntax and vocabulary. Finally, as Norman lords, like William himself, often kept their own lands back home, the politics, economics, and cultures of the two countries became intertwined with sometimes drastic consequences in the coming centuries. England was already developing under the Anglo-Saxons into a powerful European kingdom but the Norman invasion certainly accelerated that process and so made England both the dominant country in the British Isles and one of the major players in the affairs of continental Europe thereafter.

Norman Conquest

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

The Norman Conquest was the military conquest of England by William, duke of Normandy, that ultimately resulted in profound political, administrative, and social changes in the British Isles. It was the final act of a complicated drama that had begun years earlier, in the reign of Edward the Confessor, last king of the Anglo-Saxon royal line.

William, duke of Normandy, had assembled a force of 4,000 to 7,000 knights and foot soldiers for the Norman Conquest.

One effect of the Norman Conquest was the eclipse of the English vernacular as the language of literature, law, and administration in Britain. Superseded in official documents and other records by Latin and then increasingly in all areas by Anglo-Norman, written English hardly reappeared until the 13th century.

Read a brief summary of this topic

Norman Conquest, the military conquest of England by William, duke of Normandy, primarily effected by his decisive victory at the Battle of Hastings (October 14, 1066) and resulting ultimately in profound political, administrative, and social changes in the British Isles.

Invasion of England

The conquest was the final act of a complicated drama that had begun years earlier, in the reign of Edward the Confessor, last king of the Anglo-Saxon royal line. Edward, who had almost certainly designated William as his successor in 1051, was involved in a childless marriage and used his lack of an heir as a diplomatic tool, promising the throne to different parties throughout his reign, including Harold Godwineson, later Harold II, the powerful earl of Wessex. The exiled Tostig, who was Harold’s brother, and Harald III Hardraade, king of Norway, also had designs on the throne and threatened invasion. Amid this welter of conflicting claims, Edward from his deathbed named Harold his successor on January 5, 1066, and Harold was crowned king the following day. However, Harold’s position was compromised, according to the Bayeux Tapestry and other Norman sources, because in 1064 he had sworn an oath, in William’s presence, to defend William’s right to the throne.

Meanwhile, on the Continent, William had secured support for his invasion from both the Norman aristocracy and the papacy. By August 1066 he had assembled a force of 4,000–7,000 knights and foot soldiers, but unfavourable winds detained his transports for eight weeks. Finally, on September 27, while Harold was occupied in the north, the winds changed, and William crossed the Channel immediately. Landing in Pevensey on September 28, he moved directly to Hastings. Harold, hurrying southward with about 7,000 men, approached Hastings on October 13. Surprised by William at dawn on October 14, Harold drew up his army on a ridge 10 miles (16 km) to the northwest.

Harold’s wall of highly trained infantry held firm in the face of William’s mounted assault; failing to breach the English lines and panicked by the rumour of William’s death, the Norman cavalry fled in disorder. But William, removing his helmet to show he was alive, rallied his troops, who turned and killed many English soldiers. As the battle continued, the English were gradually worn down; late in the afternoon, Harold was killed (by an arrow in the eye, according to the Bayeux Tapestry), and by nightfall the remaining English had scattered and fled. William then made a sweeping advance to isolate London, and at Berkhamstead the major English leaders submitted to him. He was crowned in Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day, 1066. Sporadic indigenous revolts continued until 1071; the most serious, in Northumbria (1069–70), was suppressed by William himself, who then devastated vast tracts of the north. The subjection of the country was completed by the rapid building of a great number of castles.

Consequences of the conquest

The extent and desirability of the changes brought about by the conquest have long been disputed by historians. Certainly, in political terms, William’s victory destroyed England’s links with Scandinavia, bringing the country instead into close contact with the Continent, especially France. Inside England the most radical change was the introduction of land tenure and military service. While tenure of land in return for services had existed in England before the conquest, William revolutionized the upper ranks of English society by dividing the country among about 180 Norman tenants-in-chief and innumerable mesne (intermediate) tenants, all holding their fiefs by knight service. The result, the almost total replacement of the English aristocracy with a Norman one, was paralleled by similar changes of personnel among the upper clergy and administrative officers.

Anglo-Saxon England had developed a highly organized central and local government and an effective judicial system (see Anglo-Saxon law). All these were retained and utilized by William, whose coronation oath showed his intention of continuing in the English royal tradition. The old administrative divisions were not superseded by the new fiefs, nor did feudal justice normally usurp the customary jurisdiction of shire and hundred courts. In them and in the king’s court, the common law of England continued to be administered. Innovations included the new but restricted body of “ forest law” and the introduction in criminal cases of the Norman trial by combat alongside the old Saxon ordeals. Increasing use was made of the inquest procedure—the sworn testimony of neighbours, both for administrative purposes and in judicial cases. A major change was William’s removal of ecclesiastical cases from the secular courts, which allowed the subsequent introduction into England of the then rapidly growing canon law.

William also transformed the structure and character of the church in England. He replaced all the Anglo-Saxon bishops, except Wulfstan of Dorchester, with Norman bishops. Most notably, he secured the deposition of Stigand, the archbishop of Canterbury—who held his see irregularly and had probably been excommunicated by Pope Leo IX—and appointed in his place Lanfranc of Bec, a respected scholar and one of William’s close advisers. Seeking to impose a more orderly structure on the English episcopacy, the king supported Lanfranc’s claims for the primacy of Canterbury in the English church. William also presided over a number of church councils, which were held far more frequently than under his predecessors, and introduced legislation against simony (the selling of clerical offices) and clerical marriage. A supporter of monastic reform while duke of Normandy, William introduced the latest reforming trends to England by replacing Anglo-Saxon abbots with Norman ones and by importing numerous monks. Although he founded only a small number of monasteries, including Battle Abbey (in honour of his victory at Hastings), William’s other measures contributed to the quickening of monastic life in England.

Norman conquest of England

The Norman conquest of England was the invasion of the Kingdom of England by William the Conqueror (Duke of Normandy), in 1066 at the Battle of Hastings and the subsequent Norman control of England. It is an important watershed event in English history for a number of reasons. The conquest linked England more closely with Continental Europe through the introduction of a Norman aristocracy, thereby lessening Scandinavian influence. It created one of the most powerful monarchies in Europe and engendered a sophisticated governmental system. The conquest changed the English language and culture, and set the stage for rivalry with France, which would continue intermittently until the nineteenth century. It remains the last successful military conquest of England.

Contents

Origins

Normandy is a region in northwest France, which in the 155 years prior to 1066 experienced extensive Viking settlement. In the year 911, French Carolingian ruler Charles the Simple had allowed a group of Vikings, under their leader Rollo, to settle in northern France with the idea that they would provide protection along the coast against future Viking invaders. This proved successful and the Vikings in the region became known as the «Northmen,» from which Normandy is derived. The Normans quickly adapted to the indigenous culture, renouncing paganism and converting to Christianity. They adopted the langue d’oïl of their new home and added features from their own Norse language, transforming it into the Norman language. They further blended into the culture by intermarrying with the local population. They also used the territory granted them as a base to extend the frontiers of the Duchy to the west, annexing territory including the Bessin, the Cotentin Peninsula, and the Channel Islands.

Meanwhile, in England the Viking attacks increased, and in 991 the Anglo-Saxon king of England Aethelred II agreed to marry Emma, the daughter of the Duke of Normandy, to cement a blood-tie alliance for help against the raiders. The Viking attacks in England grew so bad that in 1013, the Anglo-Saxon kings fled and spent the next 30 years in Normandy, not returning to England until 1042.

When the Anglo-Saxon king Edward the Confessor died a few years later in 1066 with no child, and thus no direct heir to the throne, it created a power vacuum into which three competing interests laid claim to the throne of England.

The first was Harald III of Norway, based on a supposed agreement between the previous King of Norway, Magnus I of Norway, and Harthacanute, whereby if either died without heir, the other would inherit both England and Norway. The second claimant to the English throne was William, Duke of Normandy because of his blood ties to Aethelred. The third was an Anglo-Saxon by the name of Harold Godwinson who had been elected in the traditional way by the Anglo-Saxon Witenagemot of England to be king. The stage was set for a battle among the three.

Conquest of England

Meanwhile William had assembled an invasion fleet of approximately 600 ships and an army of 7000 men. This was far greater than the reserves of men in Normandy alone. William recruited soldiers from all of Northern France, the low countries, and Germany. Many soldiers in his army were second- and third-born sons who had little or no inheritance under the laws of primogeniture. William promised that if they brought their own horse, armor, and weapons to join him, they would be rewarded with lands and titles in the new realm.

After being delayed for a few weeks by unfavorable weather, he arrived in the south of England just days after Harold’s victory over the Norwegians. The delay turned out to be crucial; had he landed in August as originally planned, Harold would have been waiting with a fresh and numerically superior force. William finally landed at Pevensey in Sussex on September 28, 1066, and assembled a prefabricated wooden castle near Hastings as a base.

The choice of landing was a direct provocation to Harold Godwinson, as this area of Sussex was Harold’s own personal domain. William began immediately to lay waste to the land. It may have prompted Harold to respond immediately and in haste rather than to pause and await reinforcements in London. Again, it was an event that favored William. Had he marched inland, he may have outstretched his supply lines, and possibly have been surrounded by Harold’s forces.

They fought at the Battle of Hastings on October 14. It was a close battle but in the final hours Harold was killed and the Saxon army fled. With no living contender for the throne of England to oppose William, this was the defining moment of what is now known as the Norman Conquest.

After his victory at Hastings, William marched through Kent to London, but met fierce resistance at Southwark. He then marched down the old Roman Road of Stane Street to link up with another Norman army on the Pilgrims’ Way near Dorking, Surrey. The combined armies then avoided London altogether and went up the Thames valley to the major fortified Saxon town of Wallingford, Oxfordshire, whose Saxon lord, Wigod, had supported William’s cause. While there, he received the submission of Stigand, the Archbishop of Canterbury. One of William’s favorites, Robert D’Oyley of Lisieux, also married Wigod’s daughter, no doubt to secure the lord’s continued allegiance. William then traveled north east along the Chiltern escarpment to the Saxon fort at Berkhamstead, Hertfordshire, and waited there to receive the submission of London. The remaining Saxon noblemen surrendered to William there, and he was acclaimed King of England around the end of October and crowned on December 25, 1066, in Westminster Abbey.

Although the south of England submitted quickly to Norman rule, resistance continued, especially in the North. After six years William moved north in 1072, subduing rebellions by the Anglo-Saxons and installing Norman lords along the way. However, particularly in Yorkshire, he made agreements with local Saxon Lords to keep control of their land (under Norman-named Lords who would «hold» the lands only from a distance) in exchange for avoidance of battle and loss of any controlling share.

Hereward the Wake led an uprising in the fens and sacked Peterborough in 1070. Harold’s sons attempted an invasion of the south-west peninsula. Uprisings also occurred in the Welsh Marches and at Stafford. William faced separate invasion attempts by the Danes and the Scots. William’s defeat of these led to what became known as The Harrying of the North in which Northumbria was laid waste to deny his enemies its resources. Many of the Norman sources which survive today were written in order to justify their actions, in response to Papal concern about the treatment of the native English by their Norman conquerors. [1]

The conquest of Wales was a gradual process, concluded only in 1282 during the reign of King Edward I. Edward also subdued Scotland, but did not truly conquer it; it retained a separate monarchy until 1603, and did not formally unite with England until 1707.

Control of England

Once England had been conquered the Normans faced many challenges in maintaining control. The Anglo-Norman speaking Normans were in very small numbers compared to the native English population. Historians estimate their number at 5,000 armored knights. [2] The Anglo-Saxon lords were accustomed to being independent from centralized government, contrary to the Normans, who had a centralized system resented by the Anglo-Saxons. Revolts had sprung up almost at once, from the time of William’s coronation, led either by members of Harold’s family or disaffected English nobles.

William dealt with these challenges in a number of ways. New Norman lords constructed a variety of forts and castles (such as the motte-and-bailey) to provide a stronghold against a popular revolt (or increasingly rare Viking attacks) and to dominate the nearby town and countryside. Any remaining Anglo-Saxon lords who refused to acknowledge William’s accession to the throne or who revolted were stripped of titles and lands, which were then re-distributed to Norman favorites of William. If an Anglo-Saxon lord died without issue the Normans would always choose a successor from Normandy. In this way the Normans displaced the native aristocracy and took control of the top ranks of power. Absenteeism became common for Norman (and later Angevin) kings of England, for example William spent 130 months from 1072 onward in France rather than in England, using writs to rule England. This situation lasted until the Capetian conquest of Normandy. This royal absenteeism created a need for additional bureaucratic structures and consolidated the English administration. Kings were not the only absentees since the Anglo-Norman barons would use the practice too.

Keeping the Norman lords together and loyal as a group was just as important, as any friction could easily give the English speaking natives a chance to divide and conquer their minority Anglo-French speaking lords. One way William accomplished this was by giving out land in a piece-meal fashion. A Norman lord typically had property spread out all over England and Normandy, and not in a single geographic block. Thus, if the lord tried to break away from the King, he could only defend a small number of his holdings at any one time. This proved an effective deterrent to rebellion and kept the Norman nobility loyal to the King.

Over the longer term, the same policy greatly facilitated contacts between the nobility of different regions and encouraged the nobility to organize and act as a class, rather than on an individual or regional base which was the normal way in other feudal countries. The existence of a strong centralized monarchy encouraged the nobility to form ties with the city dwellers, which was eventually manifested in the rise of English parliamentarianism.

William disliked the Anglo-Saxon Archbishop of Canterbury, Stigand, and in 1070 maneuvered to replace him with the Italian Lanfranc and proceeded to appoint Normans to church positions.

Significance

The changes that took place because of the Norman Conquest were significant for both English and European development.

Language

One of the most obvious changes was the introduction of the Latin-based Anglo-Norman language as the language of the ruling classes in England, displacing the Germanic-based Anglo-Saxon language. Anglo-Norman retained the status of a prestige language for nearly 300 years and has had a significant influence on modern English. It is through this, the first of several major influxes of Latin or Romance languages, that the predominant spoken tongue of England began to lose much of its Germanic and Norse vocabulary, although it retained Germanic sentence structure in many cases.

Governmental systems

Even before the Normans arrived, the Anglo-Saxons had one of the most sophisticated governmental systems in Western Europe. All of England had been divided into administrative units called shires of roughly uniform size and shape, and were run by an official known as a «shire reeve» or «sheriff.» The shires tended to be somewhat autonomous and lacked coordinated control. Anglo-Saxons made heavy use of written documentation, which was unusual for kings in Western Europe at the time and made for more efficient governance than word of mouth.

The Anglo-Saxons also established permanent physical locations of government. Most medieval governments were always on the move, holding court wherever the weather and food or other matters were best at the moment. This practice limited the potential size and sophistication of a government body to whatever could be packed on a horse and cart, including the treasury and library. The Anglo-Saxons established a permanent treasury at Winchester, from which a permanent government bureaucracy and document archive had begun to grow.

This sophisticated medieval form of government was handed over to the Normans and grew even stronger. The Normans centralized the autonomous shire system. The Domesday Book exemplifies the practical codification which enabled Norman assimilation of conquered territories through central control of a census. It was the first kingdom-wide census taken in Europe since the time of the Romans, and enabled more efficient taxation of the Norman’s new realm.

Systems of accounting grew in sophistication. A government accounting office, called the exchequer, was established by Henry I; from 1150 onward this was located in Westminster.

Anglo-Norman and French relations

Anglo-Norman and French political relations became very complicated and somewhat hostile after the Norman Conquest. The Normans still retained control of the holdings in Normandy and were thus still vassals to the King of France. At the same time, they were the equals as King of England. On the one hand they owed fealty to the King of France, and on the other hand they did not, as they were peers. In the 1150s, with the creation of the Angevin Empire, the Plantagenets controlled half of France and all of England as well as Ireland, dwarfing the power of the Capetians. Yet the Normans were still technically vassals to France. A crisis came in 1204 when the French king Philip II seized all Norman and Angevin holdings in mainland France except Gascony. This would later lead to the Hundred Years War when Anglo-Norman English kings tried to regain their dynastic holdings in France.

During William’s lifetime, his vast land gains were a source of great alarm by not only the king of France, but the counts of Anjou and Flanders. Each did his best to diminish Normandy’s holdings and power, leading to years of conflict in the region.

English cultural development

One interpretation of the Conquest maintains that England became a cultural and economic backwater for almost 150 years. Few kings of England actually resided for any length of time in England, preferring to rule from cities in Normandy such as Rouen and concentrate on their more lucrative French holdings. Indeed, a mere four months after the Battle of Hastings, William left his brother-in-law in charge of the country while he returned to Normandy. The country remained an unimportant appendage of Norman lands and later the Angevin fiefs of Henry II.

Another interpretation is it that the Norman duke-kings neglected their continental territories, where they in theory owed fealty to the kings of France, in favor of consolidating their power in their new sovereign realm of England. The resources poured into the construction of cathedrals, castles, and the administration of the new realm arguably diverted energy and concentration away from the need to defend Normandy, alienating the local nobility and weakening Norman control over the borders of the territory, while simultaneously the power of the kings of France grew.

The eventual loss of control of continental Normandy divided landed families as members chose loyalty over land or vice-versa.

A direct consequence of the invasion was the near total loss of Anglo-Saxon aristocracy, and Anglo-Saxon control over the Church in England. As William subdued rebels, he confiscated their lands and gave them to his Norman supporters. By the time of the Domesday Book, only two English landowners of any note had survived the displacement. By 1096, no church See or Bishopric was held by any native Englishman; all were held by Normans. No other medieval European conquest had such devastating consequences for the defeated ruling class. Meanwhile, William’s prestige among his followers increased tremendously as he was able to award them vast tracts of land at little cost to himself. His awards also had a basis in consolidating his own control; with each gift of land and titles, the newly created feudal lord would have to build a castle and subdue the natives. Thus was the conquest self-perpetuating.

Legacy

The extent to which the conquerors remained ethnically distinct from the native population of England varied regionally and along class lines, but as early as the twelfth century the Dialogue on the Exchequer attests to considerable intermarriage between native English and Norman immigrants. Over the centuries, particularly after 1348 when the Black Death pandemic carried off a significant number of the English nobility, the two groups largely intermarried and became barely distinguishable.

The Norman conquest was the the last successful «conquest» of England, although some historians identify the Glorious Revolution of 1688 as the most recent successful «invasion.» The last full scale invasion attempt was by the Spanish Armada, which was defeated at sea by the Royal Navy and the weather. Napoleon and Hitler both prepared invasions of Great Britain, but neither was ever launched (for Hitler’s preparations see Operation Sealion). Some minor military expeditions to Great Britain were successful within their limited scope, such as the 1595 Spanish military raid on Cornwall, small scale raids on Cornwall by Arab slavers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Dutch raid on the Medway towns’ shipyards in 1667, and the American raid on Whitehaven during the American Revolutionary War.

For the importance of the concept in mass culture, note the spoof history book 1066 and All That as well as the iconic status of the Bayeux Tapestry.

Similar conquests include the Norman conquests of Apulia and Sicily (see Two Sicilies), the Principality of Antioch, and Ireland.

Alan Ayckbourn wrote a series of plays entitled The Norman Conquests. Their subject matter has nothing to do with the Norman conquest of England.

England-related topics England-related topics | |

|---|---|

| History | Logres · Roman Britain · Anglo-Saxon England · The Blitz · Elizabethan era · Civil War · Jacobean era · Kingdom of England · Norman Conquest · English Reformation · English Renaissance · Tudor period · Union with Scotland · Wars of the Roses |

| Politics | Government of England · Elizabethan government · Parliament of England · Monarchy of England · National Flag · List of English flags · Royal Arms |

| Geography | Regions · Counties · Districts · Gardens · Islands · Places · Towns · Parishes |

| Demographics | English English · Famous English people · English people |

| Culture | Castles · Church of England · Education · England cricket team · The Football Association · Museums · English rugby team · Innovations & discoveries · English cuisine · St George’s Day · Anglosphere · Anglophile |

Notes

References

External links

All links retrieved December 10, 2018.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

In what century was the norman invasion on the british isles ответ

In 1066 William, the Duke of Normandy, began to gather an army to invade Britain. The pretext for the invasion was William’s claims to the English throne. He was related to the king who died in 1066.

According to the English law it was the Witenagemot that chose the next king. If the late king left a grown-up son he was almost sure to be chosen; if not, the King’s Council of wise men would offer the Crown to some other near relative of the dead king. The king who died in 1066 had no children and Duke William cherished the hope that he would succeed to the English throne. But the Witenagemot chose another relative of the deceased king, the Anglo-Saxon Earl, Harold. William of Normandy claimed that England belonged to him and he began preparations for a war to fight for the Crown.

William sent messengers far and wide to invite the fightingmen of Western Europe to join his forces. He called upon all the Christian warriors of Europe to help him gain his rights to the English throne. No pay was offered, but William promised land to all who would support him. William also asked the Roman Pope for his support. He promised to strengthen the Pope’s power over the English Church. And the Church with the Roman Pope at the head blessed his campaign and called it a holy war. There were many fighting men who were ready to join William’s army since it was understood that English lands would be given to the victors.

William mustered a numerous army which consisted not only of the Norman barons and knights but of the knights from other parts of France. Many big sailing-boats were built to carry the army across the Channel. William landed in the south of England and the battle between the Normans and the Anglo-Saxons took place on the 14th of October 1066 at a little village in the neighbourhood of the town now called Hastings.