Installation art what is it

Installation art what is it

Installation Art

Important Art Pieces

Obliteration Room (2012)

Installation by Yayoi Kusama

Queensland Gallery of Modern Art.

Starting with a room painted from top

to bottom in pure white Japanese artist

Yayoi Kusama then unleashed into it

thousands of kids armed with thousands

of coloured stickers.

The Sequence (2008) by Arne Quinze.

A wooden sculpture-installation at the Flemish Parliament in Brussels.

Postmodernist public art.

Instant Karma

Installation by Korean installation

artist Do-Ho Suh. An attempt to

represent the Theory of karma in

three dimensional visual art.

BRITISH INSTALLATION ART

For some of the best installation

artists, see: Turner Prize Winners.

Because an installation usually allows the viewer to enter and move around the configured space and/or interact with some of its elements, it offers the viewer a very different experience from (say) a traditional painting or sculpture which is normally seen from a single reference point. Furthermore, an installation may engage several of the viewer’s senses including touch, sound and smell, as well as vision.

As in all general forms of conceptual art, installation artists are more concerned with the presentation of their message than with the material used to present it. However, unlike ‘pure’ conceptual art, which is supposedly experienced in the minds of those introduced to it, installation art is more grounded and remains tied to a physical space. Conceptual and installation art are two of the most popular examples of postmodernist art, a general tendency noted for its attempts to expand the definition of art. Both forms are widely exhibited in many of the world’s best galleries of contemporary art.

For other new art styles see Contemporary Art Movements (1970 onwards).

MEANING OF ART?

For an guide to aesthetics, see:

Art Definition, Meaning.

HISTORY OF THE ARTS

For a list of important dates about

movements, schools, famous styles,

from the Stone Age to 20th Century,

see: History of Art Timeline.

VISUAL ARTS CATEGORIES

Definitions, forms, styles, genres,

periods, see: Types of Art.

Types of Installations

Some compositions are strictly indoor, while others are public art, constructed in open-air community spaces, or projected on public buildings. Some are mute, while others are interactive and require audience participation.

Installations On Tour

Difference Between Sculpture and Installation

Famous Installation Artists

TO SEARCH FOR A PARTICULAR MOVEMENT,

BROWSE OUR A-Z of ART MOVEMENTS

For information about avant-garde art, see: Homepage.

What Is Installation Art? 10 Artworks That Made History

From pill packets and crumpled trash bags to mirrored rooms and giant mushrooms, installation art has provided some of the most adventurous and boundary-pushing masterpieces of all time.

Installation art is one of the most powerful and immersive of all art forms. In contrast with traditional mediums such as painting and sculpture, installation art is designed to fill whole rooms or even entire gallery spaces. Emerging as a bona fide art movement in the 1960s, installation art has since become one of the most popular and widespread strands of contemporary art practice, with artists embracing ever more adventurous and playful ways of transforming the gallery experience.

Many artists design tailor-made installation art to fit into a certain space, changing it into an entirely new arena. Scaffolding, false walls, mirrors, and even entire playgrounds have filled contemporary art spaces, while light and sound effects are also a common feature. Audience interaction is a vital aspect of installation art; visitors have been encouraged to crawl under huge towers, squeeze past giant mushrooms, or trigger sensors with the movement of their body. The rise of digital technology has undoubtedly impacted this interactive strand of installation art, offering artists a vast wealth of new possibilities like never before.

A Brief History of Installation Art

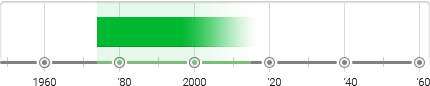

In the 1950s ‘happenings’ were all the rage across the United States, with artists including Claes Oldenberg and Allan Kaprow merging experimental performance art with crudely assembled objects, often with a politicized agenda. By the 1960s the term ‘installation art’ had been adopted by leading publications including Artforum, Arts Magazine and Studio International to describe a huge rising trend for assemblages and environments. These artworks deliberately evaded the art market, since they were almost impossible to sell and had to be taken apart at the end of the exhibition. Instead, they have lived on through photographic documentation, known as an ‘installation shot.’

Are you enjoying this article?

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription

Since this time installation art has remained a mainstay of contemporary art practice and it is more diverse and experimental than ever. From prismatic displays of digital data to teetering towers on the brink of collapse, here are some of the most revolutionary and influential installations from throughout art history.

1. Allan Kaprow, Yard, 1961

American artist Allan Kaprow’s Yard, 1961, signaled a new era in art history. The artist filled the outdoor backyard of New York’s Martha Jackson Gallery to the brim with black rubber auto tires and tarpaper-wrapped forms before inviting willing participants to climb, jump and frolic like children in this giant playground. His iconic installation art opened up new, sensorial experiences for visitors and allowed them to engage with art like never before. As well as exploring abstract ideas around solids and voids in space, Kaprow also brought improvisation and group participation into his art, taking it closer to the reality of ordinary life, as he explains, “Life is much more interesting than art. The line between art and life should be kept as fluid, and perhaps indistinct, as possible.”

2. Joseph Beuys, The End of the Twentieth Century, 1983-5

3. Cornelia Parker, Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View, 1991

British artist Cornelia Parker’s Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View, 1991, is one of the most striking and memorable installation artworks of recent times. To create this work, Parker filled an old shed with domestic junk including old toys and tools, before having the entire shed exploded in a field by the British Army. She then gathered together all the fragments left behind and suspended them mid-air as if permanently suspended in the ‘b’ of the bang. When set amidst eerie lighting these once familiar items become abstracted and unrecognizable fragments, while the title ‘Cold Dark Matter’ further emphasizes a sense of gothic mystery, referencing what Parker calls, “matter in the universe that hasn’t yet been measured.”

4. Damien Hirst, Pharmacy, 1992

5. Carsten-Höller, Mushroom Room, 2000

With all the magical mystery of a childhood fairy-tale, Belgian artist Carsten Holler’s Mushroom Room, 2000 is a treat for the senses. Holler deliberately selected the red-and-white agaric fungus because of its psychoactive qualities, grossly exaggerating their size, colors, and textures to amplify their dramatic impact. Suspending them from the ceiling upside down forces visitors to squeeze and duck their way through them, turning this installation art into an interactive experience that engages the entire body and mind. Holler likens the transformative power of these mushrooms to the act of viewing and interacting with a work of art, arguing both can induce the same mind-altering experience of imaginative awakening that is at the core of creative thinking.

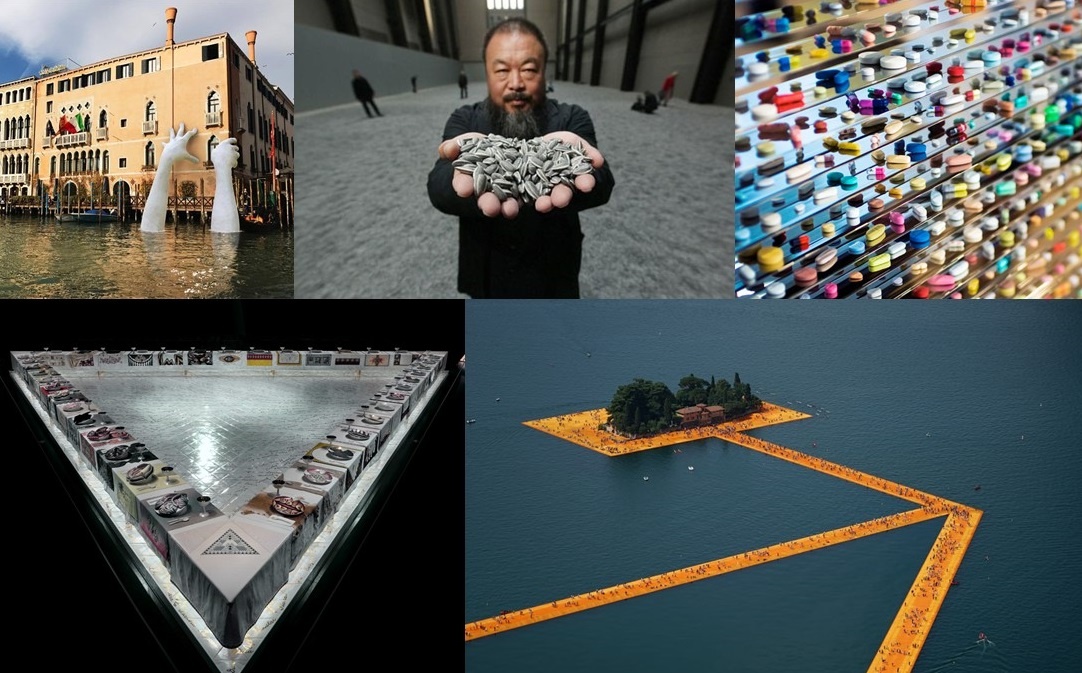

6. Olafur Eliasson, The Weather Project, 2003

Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson designed his impressively ambitious installation artwork The Weather Project, 2003 for Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, replicating the effect of a huge sun emerging through a fine mist. Low-frequency lamps around his artificial sun allowed only the golden glow of the sun to dominate the space, reducing all surrounding colors to the magical shades of gold and black. Master of illusion, Eliasson made his glowing orb from a semi-circle of light which is reflected by mirrored panels on the ceiling that complete the circle, lending the upper half of the sun a hazy, shimmering quality that mimics the real sun. These mirrored panels continued across the entire ceiling, allowing visitors to see themselves reflected as if floating in the sky above them, creating the sensation of hovering weightlessly in space.

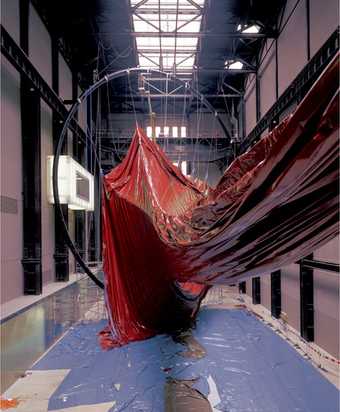

7. Anish Kapoor, Svayambh, 2007

Described by art critic Adrian Searle as “a very fine mess,” British-Indian sculptor Anish Kapoor’s Svayambh, 2007, is both ludicrous and astonishing. Made from 30 tonnes of soft wax and pigment, a slow train moves back and forth on a specially designed track between the pristine arches of the museum (he has made several versions for different institutions) leaving in its wake an unbelievably messy trail of sticky, gooey matter. Kapoor’s installation art ‘train’ is a colossal 10 meters long and ignites our senses on numerous levels, through texture, surface, smell, and color; the distinctive shade of primitive red seen in this and many of his other works seems tied to our most basic and fundamental human instincts.

8. Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Mirrored Room – The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away, 2013

Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama ’s Infinity Mirrored Room – The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away, 2013 is one of many immersive ‘Infinity Rooms’ which have fascinated gallery-goers around the world. Made by installing mirrored panels around the walls, ceiling, and floors of a small, enclosed space, Kusama then fills it with tiny networks of colored lights or objects that refract around the room and create the effect of endless, infinite space. Visitors entering her room walk along a mirrored walkway and see prismatic reflections of themselves scattered all around the room, surrounded by colored light. Much like entering a star-filled universe or merging into the digital superhighway, there’s nothing quite like the experience of an Infinity Room.

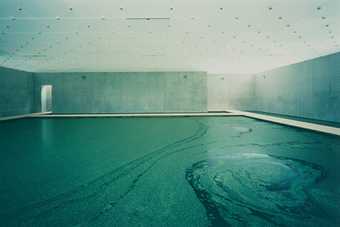

9. Random International, Rain Room, 2013

Random International’s much-celebrated installation artwork Rain Room, 2013, concisely merges art and technology into one. Visitors can pass through a gushing torrent of rainwater but miraculously remain dry, as sensors detect their movement and cause the rain to stop around them. This deceptively simple idea from the London-based collective embraces a natural symbiosis between art and viewer as the installation only comes alive through physical engagement. The artists of Studio International also tap into the fundamental role of technology in harnessing and stabilizing our natural environment, suggesting we can have a positive and mutually beneficial relationship with our landscape, rather than exploiting it for personal short-term gain. Made for temporary gallery spaces around the world, the first permanent installation of Rain Room was installed at the Sharjah Art Foundation in the United Arab Emirates in 2018.

10. Phyllida Barlow, Dock, 2014

In Phyllida Barlow’s Dock, 2014, made for Tate Britain, a series of huge haphazard assemblages made from found debris are nailed together and suspended around the room. Piles of scrap wood are hastily tacked together to form flimsy-looking scaffolding, onto which bundles of brightly colored fabric, old trash bags, and discarded clothing are bound with reams of colored tape. There is something ridiculously playful and appealing about Barlow’s knocked-up arrangements, tapping into a child-like desire to construct something from nothing. But more importantly, the sense of urgency and flux her upcycled arrangements create seems to reflect the anxious instability of living in the contemporary urban environment.

The Legacy of Installation Art

Since its conception, installation art has remained one of the most dominating mediums of contemporary art. With advancing technologies, more artists are now focussing on interactive digital installations, and this advancement has opened doors to entirely new possibilities for installation art and its relevance in today’s society. Its unifying power and immersive connection with the viewer makes installation art a revelation that continues to constantly reinvent itself.

READ NEXT:

In Defense of Contemporary Art: Is There A Case To Be Made?

By Rosie Lesso MA Contemporary Art Theory, BA Fine Art Rosie is a contributing writer and artist based in Scotland. She has produced writing for a wide range of arts organizations including Tate Modern, The National Galleries of Scotland, Art Monthly, and Scottish Art News, with a focus on modern and contemporary art. She holds an MA in Contemporary Art Theory from the University of Edinburgh and a BA in Fine Art from Edinburgh College of Art. Previously she has worked in both curatorial and educational roles, discovering how stories and history can really enrich our experience of art.

Installation Art: lesson ideas

Do your students understand modern art? Once my student, a 15-year-old girl, asked to talk about modern art. Her class visited an exhibition in Erarta, a museum of modern art in Saint-Petersburg, Russia, and she was so disappointed, irritated, angry at herself for not understanding that genre. As it’s impossible to squeeze everything about modern art into one lesson, I’ve chosen to start the ‘exploration’ with installations first.

Below I have collected ideas that you can choose, adapt to your students’ level and needs. Upon completion of this lesson, students will be able to explain what installation art is, name the most famous works, and create their work of modern art.

Task 1 — Warm-up

Start the lesson with a discussion of what modern art is. You can use some resources designed by The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA, New York), The Tate Modern (London), The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (San Francisco, USA), and other museums.

Then let your students take a quiz and check if they can distinguish between modern art and children’s drawings.

Task 2 — Lead-in

Look at the zoomed pictures. What can you see? What type of art is it?

Support by Lorenzo Quinn

Sunflower Seeds by Ai Weiwei

Lullaby Spring by Damien Hirst

The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago

Floating Piers by Christo and Jeanne-Claude

Task 3 — Installation Art: general information

In pairs, students brainstorm answers to the questions below.

Then they read the text and check their guesses.

The emergence of installations as an artistic genre has changed the face of art. Involving objects in a space, installation art presents three-dimensional works that are often site-specific and designed to transform the perception of a space. Mostly temporary and large in scale, installation art draws the viewer in, engaging them in multiple ways and making them a part of the art. In this way, art becomes something you can touch, hear, feel or smell. Some people consider sculptures and installations similar. But, in fact, they can be viewed as an inverse of one another. Sculptures are designed to be viewed from the outside as a self-contained arrangement of forms whereas installations often envelop the viewer in the space of the work. Installations focus more on the arrangement, use of space, and surrounding environment within the artwork, artwork is seen as a whole together with the site the work is set in. Viewers are able to enter, move around, and interact with it in a way not possible with paintings and sculptures.

An art installation is actually a relatively new genre of contemporary art. In 1958, the artist Allan Kaprow spoke of the “environment” to describe his productions, which consisted of the creation of a room requiring the intervention or the situation of the spectator and the place in a sort of happening, later described as “performance.” Installation art came to prominence in around the 1970s. Many credits the start of this genre of art to Marcel Duchamp’s work, and Kurt Schwitters’ Merz art objects around this time.

Public installation art is an effective way of grabbing attention while imparting subversive social commentary. The element of interactivity keeps engagement with these artworks ongoing. Global awareness helps make public installations etched in viewers’ cultural memory of the cities they inhabit.

Alternatively, watch this video to get general information about installations:

Task 4 — Famous installations

Option 1: Famous installations of all time.

Ask your students to read the descriptions and match them with the works from task 2.

Support

Sunflower

Lullaby Spring

The Dinner Party

Floating Piers

An American artist, art educator, and writer, Judy Chicago is best known for her large collaborative art installation pieces which examine the role of women in history and culture. As one of the pioneers of the Feminist Art Movement in the 1970s, she called attention to women’s roles as artists and aimed to alter the conditions under which art was produced and received. As an attempt to redress women’s traditional underrepresentation in the visual arts, she placed the female subject in the center of her practice. Her most celebrated piece ____ from 1979 celebrated the achievements of women throughout history, featuring explicit vaginal imagery. She also employed “domestic” and “feminine” arts such as needlework and embroidery, introducing them to the world of high art.

Christo and his wife Jeanne-Claude enhanced the genre of land art, presenting a different approach to the environment and raising our expectations of it. Creating large-scale installations such as wrapping of the Reichstag in Berlin, Running Fence in Sonoma, and The Gates in New York City’s Central Park, they have repeatedly rejected all theories that their projects contain any kind of deeper meaning other than their immediate aesthetic impact. In 2016 Christo created the most ambitious project ever. ____ was a monumental installation in Italy that consisted of a 3 kilometers long runway that floats on water, allowing people to walk freely across it. What is incredible is how the artist empowered people to take this temporary street and making it theirs as if they were living a fantasy. When asked about their experience people responded things like: “It’s massive, it’s hard to describe, we’re so excited”, “It’s like walking on water. It’s wonderful”; others even said it felt like walking on the back of a whale

Known as one of the most discussed works on display in 2017, ____ gives Venice a ‘helping hand’ as many critics and fans have praised. The installation depicts two striking white hands that reach out from the Grand Canal to support the historic building of the Ca’ Sagredo Hotel. Quinn’s aim was to show the potential of human nature, the power that rests in our hands, and its lasting effect on the environment. People can help create or destroy the world around them, and Quinn hopes his piece inspires discussion on global warming and climate change.

____ is considered Hirst’s most expensive work for its value in dollars (2 million), It is a steel and glass cabinet holding 6,136 individually painted pills. Evoking the natural cycle of the passing seasons, ____ reminds us of the constancy of nature’s rebirth that has continued unabated for thousands of years.

Option 2: Best installations of ….

Choose a year and create a reading task with the descriptions of installations.

Best installations of 2020

Best installations of 2019

Best installations of 2018

Best installations of 2017

Best installations of 2016

Task 5 — Creating an installation

Watch the video about ways of creating installations:

Task 6 — Speaking about art

If you are preparing students for IELTS, here are the questions that you can use to talk about installation art:

Speaking, part 1:

Do you consider installation an art form?

What art form do you like best?

Speaking, part 2:

Describe a work of art that you really like. Tell:

What it looks like

Where you first saw it

Why you like it

Speaking, part 3:

How has art changed in the last few decades in your country?

Task 7 — New installations

Finish the lesson with a project. Ask your students to roll dice to choose the topic and create drafts with their installations. They should think over the design, size, materials, meaning, environment.

Installation: Lockdown madness

Installation: 2020

Installation: Perspectives

Installation: Together apart

Installation: Puzzle

Installation: Dreamland

But is it installation art?

What does the term ‘installation art’ mean? Does it apply to big dark rooms that you stumble into to watch videos? Or empty rooms in which the lights go on and off?

What does the term ‘installation art’ mean? Does it apply to big dark rooms that you stumble into to watch videos? Or empty rooms in which the lights go on and off? Or chaotic spaces brimming with photocopied newspapers, books, pictures and slogans? The Serpentine Gallery announced its summer exhibition of work by Gabriel Orozco with the claim that he is ‘the leading conceptual and installation artist of his generation’ – yet the show comprised paintings, sculptures and photography. Almost any arrangement of objects in a given space can now be referred to as installation art, from a conventional display of paintings to a few well-placed sculptures in a garden. It has become the catch-all description that draws attention to its staging, and as a result it’s almost totally meaningless.

But did installation art ever denote anything? In the 1960s, the word installation was employed by magazines such as Artforum, Arts Magazine and Studio International to describe the way in which an exhibition was arranged, and the photographic documentation of this arrangement was called an installation shot. The neutrality of the term was an important part of its appeal, particularly for artists associated with Minimalism who rejected the messy expressionistic ‘environments’ of their immediate precursors (such as Allan Kaprow and Claes Oldenburg). Minimalism drew attention to the space in which the work was shown, and gave rise to a direct engagement with this space as a work in itself, often at the expense of any objects. Since then, the distinction between installation art and an installation of works of art has become blurred. Both point to a desire to heighten the viewer’s awareness of how objects are positioned (installed) in a space, and of our response to that arrangement. But there are important differences. A room of paintings by Glenn Brown is not the same as a room of paintings by Ilya Kabakov – because the environment in which Kabakov’s are installed (a fictional Soviet museum) is also part of the work. In a piece of installation art – such as Kabakov’s – the whole situation in its totality claims to be the work of art. Glenn Brown’s paintings, by contrast, exist as separate entities. This totalising approach has often led viewers and critics to think about installation art as an immersive experience. By making a work large enough for us to enter, installation artists are inescapably concerned with the viewer’s presence, or as Kabakov puts it: ‘The main actor in the total installation, the main centre toward which everything is addressed, for which everything is intended, is the viewer.’ He reiterates one of the dominant themes of installation art since it emerged in the 1960s: the desire to provide an intense experience for the viewer. Over the following decade, this activation of the spectator became seen as an alternative to the pacifying effects of mass-media television, mainstream film and magazines. For artists such as Vito Acconci, interactivity could function as an artistic parallel for political activism. As Acconci noted, this kind of engagement ‘could lead to a revolution’. In Brazil, which suffered a brutal military dictatorship during the 1960s and 1970s, the installations of Hélio Oiticica (1937–1980), for example, focused on the idea of individual freedom from oppressive governmental forces. He developed the term ‘supra-sensorial’, which he hoped could ‘release the individual from his oppressive conditioning’ by the state. Inviting viewers to walk barefoot on sand and straw, or to listen to Jimi Hendrix records while relaxing in a hammock, Oiticica advocated the radical potential of hanging out, rather than complying with society’s demands.

Bruce Nauman’s installations of the same period are emphatically less mellow experiences. Although concerned, like Oiticica, with our bodily response to space, his works often thwart our anticipated experience of it through video feedback, mirrors and harsh coloured lighting. His austere video corridors of the 1970s aimed to make us feel out of sync with our surroundings: ‘My intention would be to set up [the work], so that it is hard to resolve, so that you’re always on the edge of one kind of way of relating to the space or another, and you’re never quite allowed to do either.’

Olafur Eliasson

The Mediated Notion

Installed at Kunsthaus Bregenz 2001

Photo: KUB/Markus Treffer © Olafur Eliasson

Installation art of the 1980s, by contrast, was more visual and lavish, often characterised by giganticism and excessive use of materials. Think of the inflated gestures of Claes Oldenburg, such as his Pickaxe 1982, but also the work of Ann Hamilton and Cildo Meireles who continued to prioritise an often disconcerting experience of bodily immediacy. In Meireles’s Volatile 1980–94, viewers enter a room of grey ash with a candle at the far end, while the air is permeated with the smell of gas. Describing this work, critic Paulo Herkenhoff wrote that ‘when you come into contact with danger, your senses become more alert: you not only see but feel with greater intensity’.

The way in which installation art insists upon the viewer’s presence in a space has necessarily led to a number of problems about how it is remembered. You have to make big imaginative leaps if you haven’t actually experienced the work first hand. Like a joke that fails to be funny when repeated, you had to be there. Despite this subjective insistence, most writers agree on the genre’s history: the importance of Modernist precursors such as El Lissitzky’s Proun Room 1923, Kurt Schwitters’s Merzbau 1933, Kaprow’s environments and happenings of the early 1960s, as well as the debates around Minimalism and post-Minimalist installation art of the 1970s. They also note its international rise in the 1980s, and its glorifcation as the institutionally approved artform par excellence of the 1990s, best seen in the spectacular pieces that fill museums such as the Guggenheim in New York and the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern. Some critics, notably those associated with October magazine, have argued that this trajectory signals the final capitulation of installation art to the culture industry. Once a marginal practice that subverted the market by being difficult – if not impossible – to sell, it is now the epicentre of institutional activity.

Olafur Eliasson

The Weather Project, 2003

Monofrequency lights, projection foil, haze machines, mirror foil, aluminium, and scaffolding

26.7 m x 22.3 m x 155.4 m

Installation in Turbine Hall, Tate Modern, London

Photo: Studio Olafur Eliasson

Courtesy the artist: neugerriemschneider, Berlin: and Tanya Bonakdar, New York

© Olafur Eliasson 2003

But is this really so? Despite the prominence of the Turbine Hall and Duveen Gallery installations at Tate Modern and Tate Britain, only a tiny fraction of installation art is ever acquired for the Collection. With their portability and durability, painting, sculpture, photography and even video are all preferred as safer investments. The Turner Prize has several times been won by video installation artists, but site-specific work has yet to scoop the award, with the exception of Martin Creed’s The lights going on and off 2001. Instead, it has become the preferred way to create high-impact gestures within ever larger exhibition spaces. It is particularly photogenic in signature architectural statements (think of Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project for the Turbine Hall, or the elaborate installation in Kunsthaus Bregenz, Peter Zumthor’s architectural landmark) or romantically half derelict ex-industrial buildings. And, incrementally, the art form gets closer to spectacle, going all out for the big ‘wow’ instead of meaningful content; Anish Kapoor’s Marsyas – the vast scarlet trumpet he installed for the Turbine Hall (2002–3) – is a good example. Matthew Barney is a similar case: the elaborate re-creations of key sets from his Cremaster films were toured around Europe before culminating in their extravagant occupation of the entire spiral of the Solomon R. Guggenheim in New York. While Barney’s pieces looked great in photographs – and even better in his films – the experience of actually wandering through these grandiloquent sets was depressingly empty.

Anish Kapoor

Marsyas being installed in the Turbine Hall

Photo: Marcus Leith and Andrew Dunkley, Tate Photography

In a recent issue of Artforum, James Meyer lamented the new trend for museums to endorse ‘an art of size’. He quoted critic Hal Foster on the Bilbao Guggenheim: ‘To make a big splash in the global pond of spectacle culture today, you have to have a big rock to drop.’ Big audiences are assumed to demand, and like, big works: wall-size video/film projections, oversize photographs and overwhelming sculptures. Rather than ‘inducing awareness and provoking thought’, wrote Meyer, this type of art is ‘marshalled to overwhelm and pacify’. Installation art increasingly solicits sponsorship, contributing to a widespread sense among artists and critics that it has reached its sell-by date. Liam Gillick observes that ‘the word/phrase [installation art] has come to signify middlebrow, low-talent earnestness of production and effect with neo-profound content. This has been compounded by the frequent use of the word to indicate any repressed spectacle in a gallery context’. Gillick, like many, is resistant to labelling himself an installation artist. Thomas Hirschhorn has repeatedly rejected installation as a description of his work, instead preferring the commercial and pragmatic resonance of the word display. Others, such as Paul McCarthy with his Piccadilly Circus 2003 or Dominique Gonzales-Foerster, insist that it is just one of many methods they embrace.

Other artists have turned installation art into a branch of interior design. Jorge Pardo’s funky décor for the café bar of K21 in Düsseldorf exemplifies this trend, as does Michael Lin’s pink oriental floor design for the lounge of the Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Pardo has also designed and built a house at 4166 Sea View Lane, Los Angeles, as both, as both his home and a work of art. It was initially subsidised by the LA Museum of Contemporary Art in conjunction with his solo exhibition there in 1998, when it was open to the public. Now it is Pardo’s property, although the museum keeps a public file, and directions to the house, at its information desk. His recent exhibition in London featured photographs of a house in Mexico which he is renovating for sale as a work of art. But unlike installation art that adopts the house as a format – such as Gregor Schneider’s endlessly reworked Dead House Ur (1984 onwards) – Pardo’s interiors are a backdrop to activity rather than the main event; any interest in perceptual immediacy or the viewer’s consciousness has dissipated into a tasteful design aesthetic, more lifestyle experience than cultural content.

John Block Drawing at the ICA, London as part of Klutterkammer 2004

Photo: Rose Hempton

Another increasingly visible aspect of installation art is the artist-curated exhibition. Mike Kelley’s The Uncanny 1993, recently re-staged at Tate Liverpool, is typical in that it operated on two levels: as an exhibition of objects by other people, and as a single work by the artist. For most viewers, The Uncanny was experienced as a collection of unsettling sculptures and polychromatic human doubles. As the critic Alex Farquharson wrote in a review of the show: ‘Instead of feeling we were in a modern art gallery, it seemed we’d stumbled on a horror film set, an eighteenth-century anatomy lesson, a hideous crime scene and an occultist tableau.’ For those familiar with Kelley’s work, it could be seen as an extension of his interest in psychoanalysis and abjection, and as an exploration of these ideas in an exhibition-installation format. Klütterkammer, John Bock’s recent show at the ICA, London, complicated this idea further. The network of tunnels, cabins and platforms that Bock constructed around the galleries served to house a selection of strange historical ephemera (such as Rasputin’s fingernails), his own work and that of the people who have influenced him (more than 40 artists, including Martin Kippenberger, Cindy Sherman, John McCracken, Matthew Barney and the Viennese Actionists). Viewers had to crawl along wooden boxes, struggle past woolly obstacles and climb rickety ladders to see the work. All the objects became tainted by the eccentric gloss of Bock’s world view, but made total sense within his haphazard wonderland of tin foil, hay bales and revoltingly felted blankets.

The variety of work detailed above demonstrates that installation art means many things. But, as Gillick observes, to speak of its ‘end’ is extremely difficult, as the term describes ‘a mode and type of production rather than a movement or strong ideological framework’. Despite the dearth of a manifesto, one can nevertheless point to a persistence of certain ideas in the work of contemporary artists who continue its tradition. These values concern a desire to activate the viewer – as opposed to the passivity of mass-media consumption – and to induce a critical vigilance towards the environments in which we find ourselves. When the experience of going into a museum increasingly rivals that of walking into restaurants, shops, or clubs, works of art may no longer need to take the form of immersive, interactive experiences. Rather, the best installation art is marked by a sense of antagonism towards its environment, a friction with its context that resists organisational pressure and instead exerts its own terms of engagement.

Installation Art

Summary of Installation Art

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

Key Artists

Overview of Installation Art

«I was totally interested in the physical world and would always be making something,» Rachel Whiteread said of her childhood, «Playing around with bits and pieces, changing them from one thing into another,» became the early inspiration for her installation work.

Artworks and Artists of Installation Art

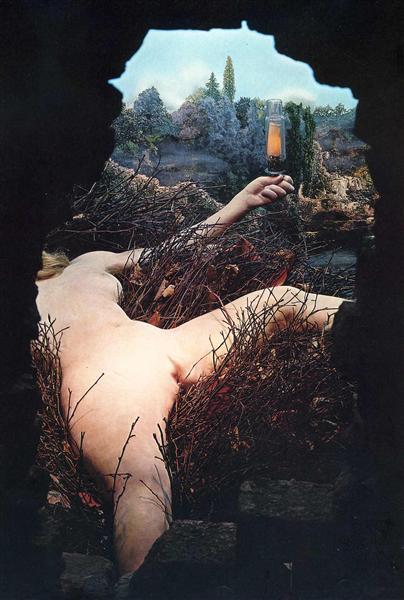

Étant donnés

Étant donnés was one of the first works to set up a specific and controlled viewing environment for audiences, which today remains a central tenet to Installation art. Duchamp surprised the art world with this three-dimensional tableau, since most believed he had decidedly retreated from art-making almost a quarter century before this, his final piece, was revealed.

The piece was described by the artist Jasper Johns as «the strangest work of art in any museum.» At the time, it was. Imagine peering through two peepholes in a wooden door to find a reclining cast of a nude woman in the forefront of a lusciously painted landscape. By crafting an experience of voyeurism, rather than simply showing a traditional nude painting on the wall, Duchamp forced the viewer into a sense of complicity. Only one person at a time could peek in, making this a very enveloping experience and creating an intimate encounter with the work’s enigmatic inhabitant.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art

The Dinner Party

The Dinner Party, an installation artwork that has become an icon of Feminist art, consists of a large triangular table adorned as a ceremonial banquet, with 39 place settings, each honoring an important woman. Each setting comprises embroidered runners, gold eating utensils, and porcelain plates that unapologetically resemble the female vulva and that vary in motif based on each specific honoree. The list of honorees includes, among others Sacajawea, Virginia Woolf, and the goddess Kali. The names of another 999 women are inscribed in gold on the white floor beneath the banquet table.

Wall Drawing #260, On Black Walls, All Two-Part Combinations of White Arcs from Corners and Sides, and White Straight, Not-Straight, and Broken Lines

Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawing #260 is one among hundreds of wall drawings started in 1969, which the artist continued to produce throughout his prolific career. Not only would LeWitt create a drawing for one specific location, he would then maintain detailed instructions on its composition so that others could duplicate it in other spaces going forward, even after his death. Even if LeWitt’s Wall Drawings are ephemeral and endlessly replicated, the idea behind their initial conception lives on undiluted.

This seminal line of work inaugurated a new relationship between drawing and architectural spaces, furthering Installation art’s site-specificity. By claiming entire walls, LeWitt’s drawings responded to the spaces they occupied and enclosed viewers in work that alternated between soothing symmetry and dazzling randomness.

These drawings were also radical inclusions into the Installation art canon because they challenged the preciousness and permanence that is expected from fine art. They are birthed in conceptualism and carried out with simple tools. They are not confined to the originating artists’ hand and they can be duplicated in multiple settings ad infinitum.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii

Smithsonian American Art Museum

My Bed

My Bed, by Tracey Emin, has inspired as much vitriol as it has critical acclaim throughout the years. The installation was a literal autobiographical presentation; the result of four bed-ridden, depressed days during which Emin accumulated debris surrounding her bed such as used condoms, blood stained underwear, and empty bottles. The piece, which the artist produced after a traumatic relationship breakdown, has been labeled self-absorbed and delusional by some, and seminal and inspired by others.

The one thing critics and enthusiasts alike can agree on is that My Bed forever changed the course of Installation art with its blatant realism. By taking her actual bed and displaying it as art Emin furthered the development of the movement’s concern with bringing a more intimate experience to the viewer. The visually narrative portrait of Emin’s life at the time and its candid nature created an engulfing atmosphere that eloquently evoked genuine experience. Audience members might either shudder in revulsion over the scene of personal debauchery or shirk guiltily inward with the knowledge that we all harbor our own dirty laundry. This piece also distanced itself resolutely from representational art as it reveled in its own mundanity and refused to stand in for any loftier concerns.

The Duerckheim Collection

Work No. 227: The lights going on and off

Martin Creed’s Work No. 227: The lights going on and off consisted of an empty room which was lit up for five seconds, and then darkened for the following five seconds in a recurring pattern. This subtle intervention with the room’s illumination, an intervention we all stage in our own homes regularly, might compel viewers to reconsider taken-for-granted elements of their everyday lives.

Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Obliteration Room

Yayoi Kusama’s Obliteration Room started out as a simple room, a completely commonplace one barring the fact that it was entirely painted over in white. Curious audience members were given a sheet of colored stickers made in accordance with the artist’s specifications, and then invited to place the stickers anywhere they liked in the blank canvas of the room. Over the course of time the surfaces were transformed into an explosion of color with thousands of conglomerated spots covering every available surface.

Kusama was careful to choose a domestic environment that audiences would find familiar so that participants, especially children, would feel comfortable engaging with the work freely. The piece was her way of engaging with the surface of an architectural space and of handing over some of the creative process to the audience, thus involving them fully in the development of this spotted interior. This dynamic piece took Installation art’s history of active viewer participation one step further by allowing them to actually co-create the work. It also allowed them to become fully immersed in an experience that significantly affected the senses but was also true to the artist’s singular voice. Kusama is famously known for suffering life-long mental illness and polka dot-infused hallucinations, so in a way, this piece invited viewers to share a vivid glimpse into her own barraged mind.

Queensland Art Gallery

The Matter of Time

Richard Serra’s primary focus is on large-scale site-specific sculptures made from industrial materials that exist in conversation with the physical spaces they occupy. According to him, «I consider space to be a material. The articulation of space has come to take precedence over other concerns. I attempt to use sculptural form to make space distinct.» Viewing these sculptures necessitates moving around and through them, and thus encountering them from constantly shifting perspectives.

The Matter of Time is an installation comprising one of Serra’s older sculptures, entitled Snake, in addition to 8 new, torqued pieces of steel. It occupies an entire gallery space in the Guggenheim Bilbao Museo. The different shapes made of weathered metal vary from simple elliptical ones to more complex spiral forms, and as viewers walk among these forms they move through varying passages of steel. The spaces between the sheets of curved metal change from being narrow and encroaching to being wide and open causing the viewer to experience constant disorientation. Serra’s choice of material, with its textured rust and spectrum of browns and oranges, adds yet another layer of visual interest to this breathtaking installation.

Guggenheim Bilbao Museo

Shibboleth

Artist: Doris Salcedo

Doris Salcedo’s Shibboleth, a winding crack in the floor that ran the length of The Tate’s Turbine Hall, managed to be both unobtrusive and intensely engaging. The Colombian artist created a fissure of varying width in the museum’s floor and placed in it a concrete cast of rock with a wire fence set inside. The crevice measures 548 feet in length, and the depth varies from being a thin opening to a more cavernous one. Salcedo’s fissure is meant to represent the immigrant experience in Europe. The title of the piece, «Shibboleth,» refers to a word, phrase, or custom that may be used to determine if someone truly belongs to a particular group or place. In a manner characteristic of Installation art, this site-specific piece engages the viewers by demanding that they come up close to the crack and then shift their distance as they encounter its variations, handing them an experience that brings to mind notions of boundaries, discomfort, and safety.

Rain Room

Artist: Random International

In Rain Room, the collaborative studio group Random International, created a fully immersive environment, which travelled to various museums and architectural spaces consisting of an entire room filled with rain. Barely lit from above, visitors stood on the periphery to take in the emulation of a natural phenomenon. As guests stepped into the rain, their body heat triggered the rain to stop only in the spaces that contained them. It was meant to give a person peaceful respite from everyday life and to provoke sensory reflection on the relationship between man and nature. It also provided viewers the opportunity to control the rain. The piece aimed to question the human experience within a machine-led world.

Rain Room represents the exciting contemporary cross section of creativity, science, and technology currently informing cutting-edge installations that expand our traditional ideas of art.

Beginnings of Installation Art

Early Influences

The earlier version of this innovative category of art was found in the expressionistic «environments,» of artists in the 1950s and ’60s such as Allan Kaprow. Kaprow curated entire gallery spaces into objects of art in which the guest might be absorbed. In his significant piece Words (1961), he installed rolls of paper with jumbled phrases and played audio recordings for the audience as they moved through the installation. Yves Klein was another pioneer of the curated environment, although his approach was a much sparser one. The Void, a piece made by Klein in 1958, featured a white gallery room, which was radically empty. It sought to validate space as an object worthy of artistic attention, thus shaping a path for Installation art.

Naming the Style: The 1970s

The term «Installation art» came of use in the 1970s to describe works attentive to the entirety of the spaces they occupied and to the audience’s viewing process. During these decades of social, political, and cultural upheaval, the art world entered a time of experimentation that blurred the boundaries between disciplines. Installation artists were increasingly interested in doing work that could be displayed unconventionally and that would take into account the viewer’s entire sensory experience. Bruce Nauman’s claustrophobic works during the 1970s, for example, played with the audience’s discomfort and aimed to make viewers feel out of sync with their surroundings. As visitors walked through his staged corridors and rooms, they experienced feelings of being locked-in or abandoned. For artists such as Vito Acconci, honing in on the audience’s discomfort was also a means of engagement. In a 1972 performance entitled Seedbed, the artist masturbated under an installed, temporary floor at the Sonnabend Gallery while visitors walked overhead and heard him voicing sexual scenarios that involved them.

Shifting Concerns

Initially, art critics focused solely on the site-specific and ephemeral nature of Installation artwork to define it, but this focus shifted as proponents of the genre began to make work referencing cultural contexts and social concerns. Debates around art’s relationship to people’s everyday socio-economic reality spurred the transformation of Installation Art, during the late 70s.

The increase in venues for contemporary art and the vogue of large-scale exhibitions in the 1980s paved the way for Installation Art’s current pervasiveness. Cildo Meireles’s Through (1983-1989), for example, was a highly politicized piece that invited viewers to move thorough a labyrinth of barriers, shattered glass, and other disconcerting obstructions. The piece was meant to be a critique of social repression, consumerism, and political censorship. Bill Viola was another artist who carefully curated environments. He was noted for his use of video technology to explore elemental human experiences. For the Installation Room for St. John of the Cross (1983), for example, Viola created a black cubicle with a viewing window through which audiences could see a small color monitor perched atop a wooden table and alongside a metal pitcher. A screen in the background showed an image of a snow-covered mountain while a voice quietly recited poetry, making this a soothing and fully immersive scene.

From the 2000s on Installation art has seen an increase in the incorporation of ever-burgeoning technological advances into works that create even more immersive environments. These highly stimulating works employ light, sensors, computers, and video realities and can be web-based, gallery-based, and even mobile-based installations. Bruce Nauman continues to work with audio recordings to create controlled situations in works such as Raw Materials (2004). The piece brings together multiple, overlapping readings of text which range in content from the stark repetition of single words to the more gasping recitation of longer texts in a sound installation. Some artists design these installation pieces so that they respond to interventions from audience members, such as in Maurice Benayoun’s Brain Factory (2016). The piece translates visitor’s emotions into visual data through a 3D printer so that audience and machine work together to produce the artwork. Brainwaves detected in the viewer are treated as abstract fodder to inform the materialization of solid objects and sculptures.

Installation Art: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Site Specificity: Location as The Integral Element

This category of art emerged during the 1960s as artists, disillusioned with the increasing commodification of the art world, began to break with artistic conventions in search of alternatives. Many Installation artists began making work that was solely created to exist in interrelationship with a particular space. Thus, if it were to be removed from said space, it would lose its meaning.

Conceptualism

Interaction and Immersion: Emphasis On Viewer Engagement

Pieces belonging to this category of Installation art shift the focus from art as a mere object to art as an instigator of dialogue. By occupying spaces so intentionally the artwork forces viewers into close interactions, so that viewing Installation art is more akin to an act of engagement than to one of contemplation. Artist Olafur Eliasson, has said, «I always try to make work that activates the viewer to be a co-producer of our shared reality.» Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang epitomizes this notion. After strategically placing gunpowder on giant surfaces or constructions, he then stages public explosions of the works that rival exciting firecracker shows. After the sparks die down, gorgeous, soot-dark paintings are left to contemplate. Another artist, Rachel Whiteread, is known for large-scale installations that provoke the audience to consider interior space. In Embankment, she filled a room at the Tate museum with hundreds of white cubes cast from the insides of empty boxes and containers. As guests walked through and around these positive impressions of negative space, they were compelled to reflect upon all the «ghosts» of internal spaces in their own lives.

Some Installation artists create fully immersive environments in order to encapsulate the viewer within an experience completely separate from reality. These pieces become like amusement park attractions or experiential activities for the visitor’s willing participation. A prime illustration is Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Room (2016), an installation inside an entire room of the Broad Museum, to which ticket-holding visitors enter one at a time to experience alone. The black room lit with thousands of tiny lights provokes feelings of being in space, or somewhere out of this world.

With the advent of technological advances, artists in this genre increasingly seek to captivate the viewer’s every sense through smell, sound, performance, and immersive video reality (all connected to the loosely used term 4-D.) Artist Nathaniel Stern’s works are often in direct collaboration with viewers as they require the movements of visitors’ body parts to influence various actions by the artwork. In one piece, enter: hektor (2001), he had guests chase projected words with their arms to trigger spoken words.

Capitalizing on Massive Scale

Grand projects that transform public places into spaces for contemplation have long belonged to the realm of Installation art, with large-scale commissions having become requisite pieces in most major art museums. These works make bold statements and tend to be crowd favorites, but some argue that large-scale pieces have become overly ubiquitous and gimmicky, with public appeal far outstripping the pieces’ artistic merit. Indeed, well known artists often seem to turn to the manufacturing of these massive Installations sure to catch the public’s fancy, and to further catapult their fame. Duo Christo and Jean-Claude, largely known for spectacular outdoor works, once filled the fifty foot by fifty foot atrium of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia with a two floors high mastaba consisting of 1,240 oil barrels that guests could barely walk around in traversing the space. Some of Anish Kapoor’s most famous work befit this category, in particular his enormous sculptural interventions into buildings that (often invasively) overtake multiple areas, rooms, and even floors.

Perception of Space

Contemporary artists continue to use Installation art as a vehicle to inform a complete, unified experience. With the advent of revolutionary technologies and a rapidly expanding digital art toolbox, it can be said that artists are only just beginning to understand the possibilities of Installation art 2.0. Recently, installation artists have been turning toward work that immerses viewers in a virtual reality such as Daniel Steegmann Mangrane’s Phantom (2015). The piece transports viewers to a Brazilian rain forest, complete with rustling leaves and imposing tree trunks. Although these new technologies haven’t yet been widely adopted by the art world, many believe they are primed to emerge as one of the foremost directions in contemporary art’s future.