She saw that he was anxious her to make a good impression

She saw that he was anxious her to make a good impression

He was anxious for her to make a good impression. She felt instinctively that

She must conceal the actress, and without effort, without deliberation, merely

Because she felt it would please, she played the part of the simple, modest,

Ingenuous girl who had lived a quiet country life.

She walked round the garden with the Colonel (она гуляла по саду с

полковником): and listened intelligently (и слушала с пониманием; intelligent —

хорошо соображающий, смышленый) while he talked of peas and asparagus

(пока он распространялся: «говорил о» горошке и спарже); she helped Mrs.

Gosselyn with the flowers (она помогала миссис Госселин с цветами) and

dusted the ornaments (и протирала от пыли декоративные украшения; to dust

— смахивать пыль, выколачивать) with which the drawing-room was crowded

(которыми была уставлена: «завалена» гостиная). She talked to her of Michael

(она говорила с ней о Майкле). She told her how cleverly he acted (она

говорила, как талантливо он играл; clever — умный, талантливый, ловкий)

and how popular he was (и каким популярным он был) and she praised his looks

(и она восхваляла его внешние данные). She saw (она видела) that Mrs.

Gosselyn was very proud of him (что миссис Госселин очень гордилась им),

and with a flash of intuition saw (и неким чутьем: «вспышкой интуиции»

увидела) that it would please her (что это доставит ей удовольствие) if she let

her see (если она даст ей увидеть), with the utmost delicacy (крайне деликатно),

as though she would have liked to keep it a secret (как если бы она хотела

сохранить это в секрете; to keep a secret — хранить тайну, не разглашать

секрет) but betrayed herself unwittingly (но выдала себя нечаянно; to betray —

изменять, предавать, выдавать), that she was head over ears in love with him

(что она по уши была влюблена в него; to be head over ears in love — быть

asparagus [q’spxrqgqs] praise [preIz] intuition [«Intjn’IS(q)n]

She walked round the garden with the Colonel and listened intelligently while

He talked of peas and asparagus; she helped Mrs. Gosselyn with the flowers

And dusted the ornaments with which the drawing-room was crowded. She

Talked to her of Michael. She told her how cleverly he acted and how popular

He was and she praised his looks. She saw that Mrs. Gosselyn was very proud

Of him, and with a flash of intuition saw that it would please her if she let her

See, with the utmost delicacy, as though she would have liked to keep it a

Secret but betrayed herself unwittingly, that she was head over ears in love

With him.

«Of course (кончено) we hope he’ll do well (мы надеемся, что он преуспеет),»

said Mrs. Gosselyn (сказала миссис Госселин). «We didn’t much like the idea

(нам не очень нравилась идея) of his going on the stage (что он пойдет в

актеры); you see (вы знаете), on both sides of the family (с обеих сторон нашей

семьи), we’re army (мы все военные: «мы армия»), but he was set on it (но он

был так решительно настроен; to be set on doing smth. — твердо решить

«Yes, of course I see what you mean (да, конечно, я понимаю, что вы имеете в

«I know it doesn’t mean so much (я знаю, что /теперь/ это не так важно: «не

значит так много») as when I was a girl (/как это было/ когда я была

девочкой), but after all (но, в конце концов) he was born a gentleman (он

джентльмен: «он был рожден джентльменом»; to bear — рожать,

производить на свет; to be born — родиться).»

«Oh, but some very nice people (о, но некоторые очень порядочные люди; nice

— хороший, приятный, милый) go on the stage nowadays (идут в актеры в

наши дни), you know (вы же знаете). It’s not like in the old days (сейчас

совершенно все по-другому: «не как в старые времена»).»

«No, I suppose not (да, я полагаю, что нет). I’m so glad (я так рада, что) he

brought you down here (он привез вас сюда). I was a little nervous about it (я

немного волновалась: «нервничала» из-за этого). I thought you’d be made-up (я

думала, что вы будете вся размалевана; made-up — искусственный,

загримированный, с большим количеством косметики) and. perhaps a little

loud (и … возможно немного вульгарной; loud — громкий, шумный,

бросающийся в глаза). No one would dream (никому и в голову не придет) you

were on the stage (что вы актриса).»

both [bqVT] nowadays [‘naVqdeIz] loud [laVd]

«Of course we hope he’ll do well,» said Mrs. Gosselyn. «We didn’t much like

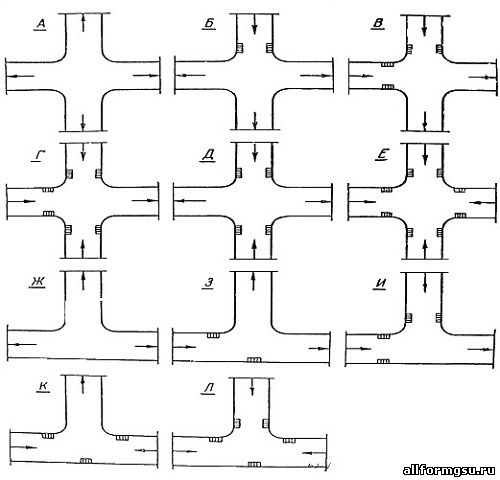

Поперечные профили набережных и береговой полосы: На городских территориях берегоукрепление проектируют с учетом технических и экономических требований, но особое значение придают эстетическим.

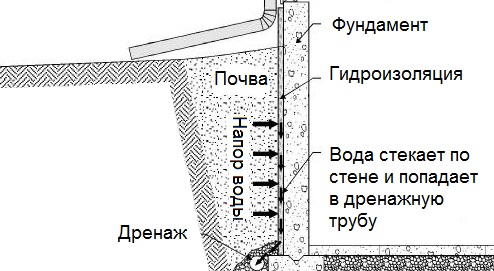

Организация стока поверхностных вод: Наибольшее количество влаги на земном шаре испаряется с поверхности морей и океанов (88‰).

Общие условия выбора системы дренажа: Система дренажа выбирается в зависимости от характера защищаемого.

She saw that he was anxious her to make a good impression

Theatre, p.4

‘If you want to be an actor I suppose I can’t stop you,’ he said, ‘but damn it all, I insist on your being educated like a gentleman.’

It gave Julia a good deal of satisfaction to discover that Michael’s father was a colonel, it impressed her to hear him speak of an ancestor who had gambled away his fortune at White’s during the Regency, and she liked the signet ring Michael wore with the boar’s head on it and the motto: Nemo me impune lacessit.

‘I believe you’re prouder of your family than of looking like a Greek god,’ she told him fondly.

‘Anyone can be good-looking,’ he answered, with his sweet smile, ‘but not everyone can belong to a decent family. To tell you the truth I’m glad my governor’s a gentleman.’

Julia took her courage in both hands.

‘My father’s a vet.’

For an instant Michael’s face stiffened, but he recovered himself immediately and laughed.

‘Of course it doesn’t really matter what one’s father is. I’ve often heard my father talk of the vet in his regiment. He counted as an officer of course. Dad always said he was one of the best.’

And she was glad he’d been to Cambridge. He had rowed for his College and at one time there was some talk of putting him in the university boat.

‘I should have liked to get my blue. It would have been useful to me on the stage. I’d have got a lot of advertisement out of it.’

Julia could not tell if he knew that she was in love with him. He never made love to her. He liked her society and when they found themselves with other people scarcely left her side. Sometimes they were asked to parties on Sunday, dinner at midday or a cold, sumptuous supper, and he seemed to think it natural that they should go together and come away together. He kissed her when he left her at her door, but he kissed her as he might have kissed the middle-aged woman with whom he had played Candida. He was friendly, good-humoured and kind, but it was distressingly clear that she was no more to him than a comrade. Yet she knew that he was not in love with anybody else. The love-letters that women wrote to him he read out to Julia with a chuckle, and when they sent him flowers he immediately gave them to her.

‘What blasted fools they are,’ he said. ‘What the devil do they think they’re going to get out of it?’

‘I shouldn’t have thought it very hard to guess that,’ said Julia dryly.

Although she knew he took these attentions so lightly she could not help feeling angry and jealous.

‘I should be a damned fool if I got myself mixed up with some woman in Middlepool. After all, they’re mostly flappers. Before I knew where I was I’d have some irate father coming along and saying, now you must marry the girl.’

She tried to find out whether he had had any adventures while he was playing with Benson’s company. She gathered that one or two of the girls had been rather inclined to make nuisances of themselves, but he thought it was a terrible mistake to get mixed up with any of the actresses a chap was playing with. It was bound to lead to trouble.

‘And you know how people gossip in a company. Everyone would know everything in twenty-four hours. And when you start a thing like that you don’t know what you’re letting yourself in for. I wasn’t risking anything.’

When he wanted a bit of fun he waited till they were within a reasonable distance of London and then he would race up to town and pick up a girl at the Globe Restaurant. Of course it was expensive, and when you came to think of it, it wasn’t really worth the money; besides, he played a lot of cricket in Benson’s company, and golf when he got the chance, and that sort of thing was rotten for the eye.

Julia told a thumping lie.

‘Jimmie always says I’d be a much better actress if I had an affair.’

‘Don’t you believe it. He’s just a dirty old man. With him, I suppose. I mean, you might just as well say that I’d give a better performance of Marchbanks if I wrote poetry.’

They talked so much together that it was inevitable for her at last to learn his views on marriage.

‘I think an actor’s a perfect fool to marry young. There are so many cases in which it absolutely ruins a chap’s career. Especially if he marries an actress. He becomes a star and then she’s a millstone round his neck. She insists on playing with him, and if he’s in management he has to give her leading parts, and if he engages someone else there are most frightful scenes. And of course, for an actress it’s insane. There’s always the chance of her having a baby and she may have to refuse a damned good part. She’s out of the public eye for months, and you know what the public is, unless they see you all the time they forget that you ever existed.’

Marriage? What did she care about marriage? Her heart melted within her when she looked into his deep, friendly eyes, and she shivered with delightful anguish when she considered his shining, russet hair. There was nothing that he could have asked her that she would not gladly have given him. The thought never entered his lovely head.

‘Of course he likes me,’ she said to herself. ‘He likes me better than anyone, he even admires me, but I don’t attract him that way.’

She did everything to seduce him except slip into bed with him, and she only did not do that because there was no opportunity. She began to fear that they knew one another too well for it to seem possible that their relations should change, and she reproached herself bitterly because she had not rushed to a climax when first they came in contact with one another. He had too sincere an affection for her now ever to become her lover. She found out when his birthday was and gave him a gold cigarette case which she knew was the thing he wanted more than anything in the world. It cost a good deal more than she could afford and he smilingly reproached her for her extravagance. He never dreamt what ecstatic pleasure it gave her to spend her money on him. When her birthday came along he gave her half a dozen pairs of silk stockings. She noticed at once that they were not of very good quality, poor lamb, he had not been able to bring himself to spring to that, but she was so touched that he should give her anything that she could not help crying.

‘What an emotional little thing you are,’ he said, but he was pleased and touched to see her tears.

She found his thrift rather an engaging trait. He could not bear to throw his money about. He was not exactly mean, but he was not generous. Once or twice at restaurants she thought he undertipped the waiter, but he paid no attention to her when she ventured to remonstrate. He gave the exact ten per cent, and when he could not make the exact sum to a penny asked the waiter for change.

‘Neither a borrower nor a lender be,’ he quoted from Polonius.

When some member of the company, momentarily hard up, tried to borrow from him it was in vain. But he refused so frankly, with so much heartiness, that he did not affront.

‘My dear old boy, I’d love to lend you a quid, but I’m absolutely stony. I don’t know how I’m going to pay my rent at the end of the week.’

For some months Michael was so much occupied with his own parts that he failed to notice how good an actress Julia was. Of course he read the reviews, and their praise of Julia, but he read summarily, without paying much attention till he came to the remarks the critics made about him. He was pleased by their approval, but not cast down by their censure. He was too modest to resent an unfavourable criticism.

‘I suppose I was rotten,’ he would say ingenuously.

His most engaging trait was his good humour. He bore Jimmie Langton’s abuse with equanimity. When tempers grew frayed during a long rehearsal he remained serene. It was impossible to quarrel with him. One day he was sitting in front watching the rehearsal of an act in which he did not appear. It ended with a powerful and moving scene in which Julia had the opportunity to give a fine display of acting. When the stage was being set for the next act Julia came through the pass door and sat down beside Michael. He did not speak to her, but looked sternly in front of him. She threw him a surprised look. It was unlike him not to give her a smile and a friendly word. Then she saw that he was clenching his jaw to prevent its trembling and that his eyes were heavy with tears.

‘What’s the matter, darling?’

‘Don

‘t talk to me. You dirty little bitch, you’ve made me cry.’

The tears came to her own eyes and streamed down her face. She was so pleased, so flattered.

‘Oh, damn it,’ he sobbed. ‘I can’t help it.’

He took a handkerchief out of his pocket and dried his eyes.

(‘I love him, I love him, I love him.’)

Presently he blew his nose.

‘I’m beginning to feel better now. But, my God, you shattered me.’

‘It’s not a bad scene, is it?’

‘The scene be damned, it was you. You just wrung my heart. The critics are right, damn it, you’re an actress and no mistake.’

‘Have you only just discovered it?’

‘I knew you were pretty good, but I never knew you were as good as all that. You make the rest of us look like a piece of cheese. You’re going to be a star. Nothing can stop you.’

‘Well then, you shall be my leading man.’

‘Fat chance I’d have of that with a London manager.’

Julia had an inspiration.

‘Then you must go into management yourself and make me your leading lady.’

He paused. He was not a quick thinker and needed a little time to let a notion sink into his mind. He smiled.

‘You know that’s not half a bad idea.’

They talked it over at luncheon. Julia did most of the talking while he listened to her with absorbed interest.

‘Of course the only way to get decent parts consistently is to run one’s own theatre,’ he said. ‘I know that.’

The money was the difficulty. They discussed how much was the least they could start on. Michael thought five thousand pounds was the minimum. But how in heaven’s name could they raise a sum like that? Of course some of those Middlepool manufacturers were rolling in money, but you could hardly expect them to fork out five thousand pounds to start a couple of young actors who had only a local reputation. Besides, they were jealous of London.

‘You’ll have to find your rich old woman,’ said Julia gaily.

She only half believed all she had been saying, but it excited her to discuss a plan that would bring her into a close and constant relation with Michael. But he was being very serious.

‘I don’t believe one could hope to make a success in London unless one were pretty well known already. The thing to do would be to act there in other managements for three or four years first; one’s got to know the ropes. And the advantage of that would be that one would have had time to read plays. It would be madness to start in management unless one had at least three plays. One of them out to be a winner.’

‘Of course if one did that, one ought to make a point of acting together so that the public got accustomed to seeing the two names on the same bill.’

‘I don’t know that there’s much in that. The great thing is to have good, strong parts. There’s no doubt in my mind that it would be much easier to find backers if one had made a bit of a reputation in London.’

It was getting on for Easter, and Jimmie Langton always closed his theatre for Holy Week. Julia did not quite know what to do with herself; it seemed hardly worth while to go to Jersey. She was surprised to receive a letter one morning from Mrs Gosselyn, Michael’s mother, saying that it would give the Colonel and herself so much pleasure if she would come with Michael to spend the week at Cheltenham. When she showed the letter to Michael he beamed.

‘I asked her to invite you. I thought it would be more polite than if I just took you along.’

‘You are sweet. Of course I shall love to come.’

Her heart beat with delight. The prospect of spending a whole week with Michael was enchanting. It was just like his good nature to come to the rescue when he knew she was at a loose end. But she saw there was something he wanted to say, yet did not quite like to.

He gave a little laugh of embarrassment.

‘Well, dear, you know, my father’s rather old-fashioned, and there are some things he can’t be expected to understand. Of course I don’t want you to tell a lie or anything like that, but I think it would seem rather funny to him if he knew your father was a vet. When I wrote and asked if I could bring you down I said he was a doctor.’

‘Oh, that’s all right.’

Julia found the Colonel a much less alarming person than she had expected. He was thin and rather small, with a lined face and close-cropped white hair. His features had a worn distinction. He reminded you of a head on an old coin that had been in circulation too long. He was civil, but reserved. He was neither peppery nor tyrannical as Julia, from her knowledge of the stage, expected a colonel to be. She could not imagine him shouting out words of command in that courteous, rather cold voice. He had in point of fact retired with honorary rank after an entirely undistinguished career, and for many years had been content to work in his garden and play bridge at his club. He read The Times went to church on Sunday and accompanied his wife to tea-parties. Mrs Gosselyn was a tall, stoutish, elderly woman, much taller than her husband, who gave you the impression that she was always trying to diminish her height. She had the remains of good looks, so that you said to yourself that when young she must have been beautiful. She wore her hair parted in the middle with a bun on the nape of her neck. Her classic features and her size made her at first meeting somewhat imposing, but Julia quickly discovered that she was very shy. Her movements were stiff and awkward. She was dressed fussily, with a sort of old-fashioned richness which did not suit her. Julia, who was entirely without self-consciousness, found the elder woman’s deprecating attitude rather touching. She had never known an actress to speak to and did not quite know how to deal with the predicament in which she now found herself. The house was not at all grand, a small detached stucco house in a garden with a laurel hedge, and since the Gosselyns had been for some years in India there were great trays of brass ware and brass bowls, pieces of Indian embroidery and highly-carved Indian tables. It was cheap bazaar stuff, and you wondered how anyone had thought it worth bringing home.

Julia was quick-witted. It did not take her long to discover that the Colonel, notwithstanding his reserve, and Mrs Gosselyn, notwithstanding her shyness, were taking stock of her. The thought flashed through her mind that Michael had brought her down for his parents to inspect her. Why? There was only one possible reason, and when she thought of it her heart leaped. She saw that he was anxious for her to make a good impression. She felt instinctively that she must conceal the actress, and without effort, without deliberation, merely because she felt it would please, she played the part of the simple, modest, ingenuous girl who had lived a quiet country life. She walked round the garden with the Colonel and listened intelligently while he talked of peas and asparagus; she helped Mrs Gosselyn with the flowers and dusted the ornaments with which the drawing-room was crowded. She talked to her of Michael. She told her how cleverly he acted and how popular he was and she praised his looks. She saw that Mrs Gosselyn was very proud of him, and with a flash of intuition saw that it would please her if she let her see, with the utmost delicacy, as though she would have liked to keep it a secret but betrayed herself unwittingly, that she was head over ears in love with him.

‘Of course we hope he’ll do well,’ said Mrs Gosselyn. ‘We didn’t much like the idea of his going on the stage; you see, on both sides of the family, we’re army, but he was set on it.’

‘Yes, of course I see what you mean.’

‘I know it doesn’t mean so much as when I was a girl, but after all he was born a gentleman.’

‘Oh, but some very nice people go on the stage nowadays, you know. It’s not like in the old days.’

‘No, I suppose not. I’m so glad he brought you down here. I was a little nervous about it. I thought you’d be made-up and. perhaps a little loud. No one would dream you were on the stage.’

(‘I should damn well think not. Haven’t I been giving a perfect performance of the village maiden for the last forty-eight hours?’)

The Colonel began to make little jokes with her and sometimes he pinched her ear playfully.

‘Now you mustn’t flirt with me, Colonel,’ she cried, giving him a roguish, delicious glance, ‘Just because I’m an actress you think you can take liberties with me.’

‘George, George,’ smiled Mrs Gosselyn. And then to Julia: ‘He always was a terrible flirt.’

(‘Gosh, I’m going down like a barrel of oysters.’)

Mrs Gosselyn told her about India, how strange it was to have all those coloured servants, but how nice the society was, only army people and Indian civilians, but still it wasn’t like home, and how glad she was to get back to England.

They were to leave on Easter Monday because they were playing that night, and on Sunday evening after supper Colonel Gosselyn said he was going to his study to write letters; a minute or two later Mrs Gosselyn said she must go and see the cook. When they were left alone Michael, standing with his back to the fire, lit a cigarette.

‘I’m afraid it’s been very quiet down here; I hope you haven’t had an awfully dull time.’

‘It’s been heavenly.’

‘You’ve made a tremendous success with my people. They’ve taken an enormous fancy to you.’

‘God, I’ve worked for it,’ thought Julia, but aloud said: ‘How d’you know?’

‘Oh, I can see it. Father told me you were very ladylike, and not a bit like an actress, and mother says you’re so sensible.’

Julia looked down as though the extravagance of these compliments was almost more than she could bear. Michael came over and stood in front of her. The thought occurred to her that he looked like a handsome young footman applying for a situation. He was strangely nervous. Her heart thumped against her ribs.

She saw that he was anxious her to make a good impression

For some months Michael was so much occupied with his own parts that he failed to notice how good an actress Julia was. Of course he read the reviews, and their praise of Julia, but he read summarily, without paying much attention till he came to the remarks the critics made about him. He was pleased by their approval, but not cast down by their censure. He was too modest to resent an unfavourable criticism.

‘I suppose I was rotten,’ he would say ingenuously.

His most engaging trait was his good humour. He bore Jimmie Langton’s abuse with equanimity. When tempers grew frayed during a long rehearsal he remained serene. It was impossible to quarrel with him. One day he was sitting in front watching the rehearsal of an act in which he did not appear. It ended with a powerful and moving scene in which Julia had the opportunity to give a fine display of acting. When the stage was being set for the next act Julia came through the pass door and sat down beside Michael. He did not speak to her, but looked sternly in front of him. She threw him a surprised look. It was unlike him not to give her a smile and a friendly word. Then she saw that he was clenching his jaw to prevent its trembling and that his eyes were heavy with tears.

‘What’s the matter, darling?’

‘Don’t talk to me. You dirty little bitch, you’ve made me cry.’

The tears came to her own eyes and streamed down her face. She was so pleased, so flattered.

‘Oh, damn it,’ he sobbed. ‘I can’t help it.’

He took a handkerchief out of his pocket and dried his eyes.

(‘I love him, I love him, I love him.’)

Presently he blew his nose.

‘I’m beginning to feel better now. But, my God, you shattered me.’

‘It’s not a bad scene, is it?’

‘The scene be damned, it was you. You just wrung my heart. The critics are right, damn it, you’re an actress and no mistake.’

‘Have you only just discovered it?’

‘I knew you were pretty good, but I never knew you were as good as all that. You make the rest of us look like a piece of cheese. You’re going to be a star. Nothing can stop you.’

‘Well then, you shall be my leading man.’

‘Fat chance I’d have of that with a London manager.’

Julia had an inspiration.

‘Then you must go into management yourself and make me your leading lady.’

He paused. He was not a quick thinker and needed a little time to let a notion sink into his mind. He smiled.

‘You know that’s not half a bad idea.’

They talked it over at luncheon. Julia did most of the talking while he listened to her with absorbed interest.

‘Of course the only way to get decent parts consistently is to run one’s own theatre,’ he said. ‘I know that.’

The money was the difficulty. They discussed how much was the least they could start on. Michael thought five thousand pounds was the minimum. But how in heaven’s name could they raise a sum like that? Of course some of those Middlepool manufacturers were rolling in money, but you could hardly expect them to fork out five thousand pounds to start a couple of young actors who had only a local reputation. Besides, they were jealous of London.

‘You’ll have to find your rich old woman,’ said Julia gaily.

She only half believed all she had been saying, but it excited her to discuss a plan that would bring her into a close and constant relation with Michael. But he was being very serious.

‘I don’t believe one could hope to make a success in London unless one were pretty well known already. The thing to do would be to act there in other managements for three or four years first; one’s got to know the ropes. And the advantage of that would be that one would have had time to read plays. It would be madness to start in management unless one had at least three plays. One of them out to be a winner.’

‘Of course if one did that, one ought to make a point of acting together so that the public got accustomed to seeing the two names on the same bill.’

‘I don’t know that there’s much in that. The great thing is to have good, strong parts. There’s no doubt in my mind that it would be much easier to find backers if one had made a bit of a reputation in London.’

IT was getting on for Easter, and Jimmie Langton always closed his theatre for Holy Week. Julia did not quite know what to do with herself; it seemed hardly worth while to go to Jersey. She was surprised to receive a letter one morning from Mrs Gosselyn, Michael’s mother, saying that it would give the Colonel and herself so much pleasure if she would come with Michael to spend the week at Cheltenham. When she showed the letter to Michael he beamed.

‘I asked her to invite you. I thought it would be more polite than if I just took you along.’

‘You are sweet. Of course I shall love to come.’

Her heart beat with delight. The prospect of spending a whole week with Michael was enchanting. It was just like his good nature to come to the rescue when he knew she was at a loose end. But she saw there was something he wanted to say, yet did not quite like to.

He gave a little laugh of embarrassment.

‘Well, dear, you know, my father’s rather old-fashioned, and there are some things he can’t be expected to understand. Of course I don’t want you to tell a lie or anything like that, but I think it would seem rather funny to him if he knew your father was a vet. When I wrote and asked if I could bring you down I said he was a doctor.’

‘Oh, that’s all right.’

Julia found the Colonel a much less alarming person than she had expected. He was thin and rather small, with a lined face and close-cropped white hair. His features had a worn distinction. He reminded you of a head on an old coin that had been in circulation too long. He was civil, but reserved. He was neither peppery nor tyrannical as Julia, from her knowledge of the stage, expected a colonel to be. She could not imagine him shouting out words of command in that courteous, rather cold voice. He had in point of fact retired with honorary rank after an entirely undistinguished career, and for many years had been content to work in his garden and play bridge at his club. He read The Times, went to church on Sunday and accompanied his wife to tea-parties. Mrs Gosselyn was a tall, stoutish, elderly woman, much taller than her husband, who gave you the impression that she was always trying to diminish her height. She had the remains of good looks, so that you said to yourself that when young she must have been beautiful. She wore her hair parted in the middle with a bun on the nape of her neck. Her classic features and her size made her at first meeting somewhat imposing, but Julia quickly discovered that she was very shy. Her movements were stiff and awkward. She was dressed fussily, with a sort of old-fashioned richness which did not suit her. Julia, who was entirely without self-consciousness, found the elder woman’s deprecating attitude rather touching. She had never known an actress to speak to and did not quite know how to deal with the predicament in which she now found herself. The house was not at all grand, a small detached stucco house in a garden with a laurel hedge, and since the Gosselyns had been for some years in India there were great trays of brass ware and brass bowls, pieces of Indian embroidery and highly-carved Indian tables. It was cheap bazaar stuff, and you wondered how anyone had thought it worth bringing home.

Julia was quick-witted. It did not take her long to discover that the Colonel, notwithstanding his reserve, and Mrs Gosselyn, notwithstanding her shyness, were taking stock of her. The thought flashed through her mind that Michael had brought her down for his parents to inspect her. Why? There was only one possible reason, and when she thought of it her heart leaped. She saw that he was anxious for her to make a good impression. She felt instinctively that she must conceal the actress, and without effort, without deliberation, merely because she felt it would please, she played the part of the simple, modest, ingenuous girl who had lived a quiet country life. She walked round the garden with the Colonel and listened intelligently while he talked of peas and asparagus; she helped Mrs Gosselyn with the flowers and dusted the ornaments with which the drawing-room was crowded. She talked to her of Michael. She told her how cleverly he acted and how popular he was and she praised his looks. She saw that Mrs Gosselyn was very proud of him, and with a flash of intuition saw that it would please her if she let her see, with the utmost delicacy, as though she would have liked to keep it a secret but betrayed herself unwittingly, that she was head over ears in love with him.

Сборник упражнений по грамматике английского языка

. Сборник упражнений по грамматике английского языка: учебное пособие для ин-тов и фак-тов иностр. яз. – 8-е изд. – М.: Высш. шк., 2003 – 432 с. – На англ. яз.

He seemed to be reading scarcely any law. [179]

“Dr Salt, what do you think you’re doing?” “People seem to have been asking me that for days,” said Dr Salt mildly. [179]

The cat seems to have been missing for about three weeks. [179]

Not going home, in fact, seemed lately to have become the pattern of his life. [179]

It seemed to have been snowing in the room. The floor, the chairs, the desk were covered in drifts of white. It was torn paper. [179]

All the family seemed to be talking at once. [179]

The general seemed to have aged a great deal. [179]

Charles met me the first day I came to London, and our friendship seemed to have been established a long time. [180]

In front of one window there was a small table and Harry was sitting at it, peering at a pile of papers which he seemed to be copying and to translating. [180]

Ex. 6. Use the required form of the infinitive in its function of part of a compound verbal predicate.

15. When I arrived there I didn’t see the dog. Not much else seemed(to change)

Ex. 7. Translate the following into English using infinitives as part of a compound verbal predicate:

1. Это оказалось правдой. (to turn out)

2. Он, кажется, получил все, что хотел. (to seem)

3. «Где мисс Стоун?» — «Она, кажется, работает в справочном отделе библиотеки». (to seem)

4. Казалось, что у него нет дружеских отношений ни с кем в отделе. (to appear)

5. Боб взглянул на мать, чтобы понять, как она реагирует на разговор. Но она, казалось, не слушала. (to seem)

6. Его сведения оказались правильными. (to turn out)

7. Казалось, что она пишет или рисует. (to seem)

8. Казалось, что сплетни эти не были восприняты моими братьями всерьез. (to seem)

9. Он, кажется, мой единственный друг. (to seem)

10. Мой отец слушал серьезно или, по крайней мере, создавалось впечатление, что он слушал. (to appear)

11. У нас, кажется, уже был этот разговор раньше. (to sееm)

12. Похоже, никто из вас не знает, как вести себя прилично. (to seem)

13. Казалось, что его удивил этот слух. (to seem)

14. Было такое впечатление, что он не слышал, что она сказала. (to appear)

15. Я не знал этого парня, но он, кажется, всем тогда нравился. (to seem)

16. Случилось так, что он был приглашен на обед к Роджеру. (to happen)

17. Так случилось, что я первый узнал об этом. (to happen)

18. Энн познакомилась со своим молодым человеком на танцах, и позже они много развлекались вместе, потому что он оказался хорошим парнем. (to prove)

ex. 8. Translate the following into English using ing-forms as part of a compound verbal predicate:

1. Он ездил верхом каждый день.

2. Она сидела, уставившись прямо перед собой.

3. Он вернулся с очень расстроенным видом.

4. Вокруг сидело несколько человек, они ели сандвичи и курили.

5. Я сказала мужу, что мне хочется пойти потанцевать.

6. Она долго лежала и плакала.

7. В то утро мальчик отправился кататься на лодке один.

8. Я ничего не сказал, и мальчик ушел, насвистывая.

9. Мы стояли и ждали, когда откроются двери.

10. В то утро я пошел купаться.

11. Она ушла в магазин.

12. При первом же порыве ветра шляпа ее мужа полетела по воздуху.

13. Они сидели и разговаривали о планах на будущее.

Ex. 9. Choose between the infinitive and the ing-form as a second action accompanying the action of the predicate verb:

3. I looked at her for a minute, not(to understand)

20. Настроение Хью не позволило мне обратиться к нему с просьбой. (to make — impossible)

Ex. 32. Choose between the infinitive and the ing-form as subjective predicative:

Ex. 33. Use the required form of the infinitive in its function of subjective predicative:

6. They were understood(to quarrel)

Ex. 34. Translate the following into English using infinitives or ing-forms as subjective predicatives:

1. Слышали, как посетитель в разговоре с моим отцом упомянул какой-то несчастный случай. (to hear)

2. Ему посоветовали не рассказывать им о своей жизни. (to advise)

3. Девочке велели разлить в чашки чай. (to tell)

4. Слышали, как несколько минут тому назад они спорили на террасе. (to hear)

5. «Я имел обыкновение украдкой уходить из дома вечером, — сказал он, — когда предполагалось, что я занимаюсь, в церковь, чтобы поиграть на органе». (to suppose)

6. Полагают, что он глубоко привязан к семье. (to believe)

7. Было известно, что он пишет книгу о войне. (to know)

8. Через окно можно было видеть, что водитель ждет у машины. (to see)

9. На этот раз меня попросили зайти к нему домой. (to ask)

10. Говорили, что он изменил свое решение. (to report)

11. Когда я позвонил в дверь, было слышно, как в холле лает собака. (to hear)

12. Было известно, что он никогда не отказывался принять пациента в любое время. (to know)

13. Ему разрешили оставить у них свою фамилию и адрес. (to allow)

14. Симон и Дик остались разговаривать в гостиной. (to leave)

15. Ей дали понять, что она должна выехать из этой квартира. (to make)

16. Кое-кто полагал, что у него есть связи с лондонским отделением фирмы. (to believe)

17. Нас оставили посмотреть фильм. (to leave)

18. Его не видно целую неделю. Говорят, что он в отпуске. (to say)

19. Ему велели прийти сюда к мистеру Эбботу. (to tell)

20. Фокса нашли ожидающим нас на террасе. (to find)

21. Билл а провели в гостиную и оставили там рассматривать картины. (to leave)

22. От нас не требуют, чтобы мы сказали, что для него хорошо, а что нет. (to require)

23. Его присутствие было неожиданным, потому что говорили, что он путешествует на Востоке. (to say)

24. Я подумал, что спички не оставляют лежать в саду просто так. (to leave)

25. Я был болен в то время, и миссис Барнаби оставили ухаживать за мной. (to leave)

26. Считалось, что она ушла от мужа. (to believe)

Ex. 35. Supply where necessary the particle to before the infinitive used as objective predicative:

Ex. 36. Choose between the infinitive and the ing-form as objective predicative:

9. I don’t like girlsIt takes away the fragrance of youth. (to smoke)

41. It might be worth(to try)

Ex. 68. Revision: translate the following into English using verbals as objective and subjective predicatives:

1. Издали виден был грузовик, поднимающийся в гору.

2. Я часто видел, как это делается.

3. Меня не пригласили пойти с ними.

4. Очень важно, чтобы это было сделано быстро.

5. Интересно, почему она не хотела, чтобы я с ними познакомился.

6. Считалось, что они прожили очень счастливую жизнь.

7. Он приказал оседлать ему лошадь и поехал в деревню.

8. Я наблюдал из окна, как Диана разговаривала с соседкой.

9. Она заставила меня переодеться к обеду.

10. Он не хотел, чтобы я соглашался.

11. Я слышал, как говорили, что Лиз могла бы стать замечательной пианисткой.

12. Сколько времени, ты полагаешь, я буду здесь стоять? 13. Видели, как она вошла в лес.

14. Мы оставили детей играть на полу.

15. Мальчиков поймали, когда они крали вишню.

16. Мы оставили детей смотреть телевизор.

17. Мне не нравится, когда девушки курят.

18. Я не допущу, чтобы ты так разговаривал со мной.

19. Она улыбнулась, когда услышала, что ее описывают как женщину среднего возраста.

20. Мне велели приготовить чай.

21. Его рассказ продолжал смешить людей.

22. Она застала всю семью в сборе.

23. Они очень давно делали эту работу и не могли себе представить, что кто-то не знает об этом.

24. Он хотел, чтобы проложили дорогу к деревне.

25. Я позволила ему сводить меня в театр.

26. Она не желает, чтобы ее местонахождение стало известным.

1. Мне было трудно их убедить.

2. Болезнь помешала ему воспользоваться этой возможностью.

3. Было бы лучше, если бы ему ничего не говорили.

4. Его присутствие позволило мне избежать ссоры.

5. Люси видела, что я был очень озабочен тем, чтобы она произвела хорошее впечатление.

6. Оказалось, что прекратить все эти слухи не так-то просто.

7. Он искал спокойное место, где бы его семья могла отдохнуть.

8. Никто из нас ничего не мог бы сделать в этой ситуации.

9. Это был удобный для нее случай поговорить с ним наедине.

10. Я попросил разрешения, чтобы Том пожил у нас еще неделю.

11. Странно, что он написал такую статью.

12. Для меня большая честь познакомиться с таким человеком, как Джон Бейли.

13. Ему доставит удовольствие все подготовить к их приезду.

14. Им было бы жаль потратить столько усилий зря.

15. Очень предусмотрительно с вашей стороны, что вы пришли сегодня.

16. Мы все ждали, когда придет письмо.

17. Просто удивительно, как это Дэн нашел вас.

18. Мне очень хотелось, чтобы он скорее приступил к работе.

19. Для меня было облегчением уехать из дома.

20. Им было бы удобно не втягивать его в это дело.

21. Ему стоило большого усилия позвонить ей.

22. Очень мило с его стороны, что он интересуется моими делами.

23. Я плотно закрыл дверь, чтобы нам никто не мешал.

24. Он жестом показал, чтобы я вышел.

Ex. 70. Revision: translate the following into English using ing-complexes:

1. Он жаловался на то, что у него в комнате очень холодно 2. Он часто говорил о том, что ему необходимо найти хорошо

оплачиваемую работу, но ничего для этого не делал.

3. В письме упоминалось, что миссис Брейн заболела.

4. Она позвала на помощь. Но у нее не было никакой надежды, что помощь придет.

5. Ей не нравилась мысль о том, что ее сын будет жить в одной комнате с каким-нибудь грубым мальчишкой.

6. Он рассказал ей, что для их сына есть возможность получить работу получше.

7. Она терзалась мыслью о том, что за ее ребенком присматривают какие-то чужие люди.

8. Когда он объявил о дне своего отплытия, она не могла сдержать радости.

9. Джулия убрала сигарету так, что он этого не заметил.

10. Твой отец настаивает на том, чтобы ты получил образование в Оксфорде.

11. Он обещал написать ей письмо, и она с нетерпением ждала, когда получит его.

Ex. 71. Revision: translate the following into English using absolute соnstructions with verbals:

1. Я увидел, что он сидел у окна и одна его рука лежала полусжатой на столе.

2. Это единственный дом там, и во всей округе некому выслеживать его.

3. Она глубоко дышала, губы ее были приоткрыты, щеки разрумянились.

4. Она плакала, не таясь и не сводя с него глаз.

5. С Мери в качестве учительницы он очень быстро научился говорить на хорошем английском языке.

6. Я не могу спать, когда не выключено радио.

7. На третьем этаже загорелось окно: кто-то работал допоздна.

8. Я ушел от них поздно вечером с чувством облегчения от груза забот.

9. Он лежал на спине с закрытыми глазами.

10. Джулия от нечего делать посещала лекции.

11. Она увидела Пэт сидящей на полу среди фотографий, разбросанных вокруг нее.

Ex. 72. Revision: translate the following into English using the proper forms of verbals:

1. Написав на конверте адрес, она выбросила открытку в корзинку для бумаг.

2. Это была любовная связь, которая, как полагали, продолжалась так давно, что о ней перестали говорить.

3. Так случилось, что они обедали у Долли в тот день.

4. Очень мило с его стороны, что он предложил это.

5. Кажется, он не написал никаких новых пьес.

6. Уплатив шоферу, он взглянул на жену, которая стояла в дверях освещенная заходящим солнцем.

7. Чувство времени — это одна из вещей, которым я, кажется, научился у Джимми.

8. Было похоже, что он получал удовольствие от нашей компании.

9. Говорили, что она еще не приняла никакого решения.

10. Ходят слухи, что ей посоветовали не выходить замуж за Теда.

11. Известно, что он был трижды ранен во время войны.

12. У меня появилось ощущение, что за мной наблюдают.

13. Я не помню, чтобы я когда-либо была около их дома.

14. Крису как-то не хотелось, чтобы над ним смеялись.

15. Так как он никогда раньше не занимал денег, он нашел целый ряд людей, которые были готовы одолжить ему небольшие суммы.

16. Я терпеть не мог, когда мне желали удачи.

She saw that he was anxious her to make a good impression

«There’s some mystery and I’m going to clear it up. That’s the only way to do it.»

«Oh, Bateman, how can you be so good and kind?» she exclaimed.

«You know there’s nothing in the world I want more than your happiness, Isabel.»

She looked at him and she gave him her hands.

«You’re wonderful, Bateman. I didn’t know there was anyone in the world like you. How can I ever thank you?»

«I don’t want your thanks. I only want to be allowed to help you.»

She dropped her eyes and flushed a little. She was so used to him that she had forgotten how handsome he was. He was as tall as Edward and as well made, but he was dark and pale of face, while Edward was ruddy. Of course she knew he loved her. It touched her. She felt very tenderly towards him.

It was from this journey that Bateman Hunter was now returned.

The business part of it took him somewhat longer than he expected and he had much time to think of his two friends. He had come to the conclusion that it could be nothing serious that prevented Edward from coming home, a pride, perhaps, which made him determined to make good before he claimed the bride he adored; but it was a pride that must be reasoned with. Isabel was unhappy. Edward must come back to Chicago with him and marry her at once. A position could be found for him in the works of the Hunter Motor Traction and Automobile Company. Bateman, with a bleeding heart, exulted at the prospect of giving happiness to the two persons he loved best in the world at the cost of his own. He would never marry. He would be godfather to the children of Edward and Isabel, and many years later when they were both dead he would tell Isabel’s daughter how long, long ago he had loved her mother. Bateman’s eyes were veiled with tears when he pictured this scene to himself.

Meaning to take Edward by surprise he had not cabled to announce his arrival, and when at last he landed at Tahiti he allowed a youth, who said he was the son of the house, to lead him to the Hotel de la Fleur. He chuckled when he thought of his friend’s amazement on seeing him, the most unexpected of visitors, walk into his office.

«By the way,» he asked, as they went along, «can you tell me where I shall find Mr. Edward Barnard?»

«Barnard?» said the youth. «I seem to know the name.»

«He’s an American. A tall fellow with light brown hair and blue eyes. He’s been here over two years.»

«Of course. Now I know who you mean. You mean Mr Jackson’s nephew.»

«Mr Arnold Jackson.»

«I don’t think we’re speaking of the same person,» answered Bateman, frigidly.

He was startled. It was queer that Arnold Jackson, known apparently to all and sundry, should live here under the disgraceful name in which he had been convicted. But Bateman could not imagine whom it was that he passed off as his nephew. Mrs Longstaffe was his only sister and he had never had a brother. The young man by his side talked volubly in an English that had something in it of the intonation of a foreign tongue, and Bateman, with a sidelong glance, saw, what he had not noticed before, that there was in him a good deal of native blood. A touch of hauteur involuntarily entered into his manner. They reached the hotel. When he had arranged about his room Bateman asked to be directed to the premises of Braunschmidt & Co. They were on the front, facing the lagoon, and, glad to feel the solid earth under his feet after eight days at sea, he sauntered down the sunny road to the water’s edge. Having found the place he sought, Bateman sent in his card to the manager and was led through a lofty barn-like room, half store and half warehouse, to an office in which sat a stout, spectacled, bald-headed man.

«Can you tell me where I shall find Mr Edward Barnard? I understand he was in this office for some time.»

«That is so. I don’t know just where he is.»

«But I thought he came here with a particular recommendation from Mr Braunschmidt. I know Mr Braunschmidt very well.»

The fat man looked at Bateman with shrewd, suspicious eyes. He called to one of the boys in the warehouse.

«Say, Henry, where’s Barnard now, d’you know?»

«He’s working at Cameron’s, I think,» came the answer from someone who did not trouble to move.

The fat man nodded.

«If you turn to your left when you get out of here you’ll come to Cameron’s in about three minutes.»

«I think I should tell you that Edward Barnard is my greatest friend. I was very much surprised when I heard he’d left Braunschmidt & Co.»

The fat man’s eyes contracted till they seemed like pin-points, and their scrutiny made Bateman so uncomfortable that he felt himself blushing.

«I guess Braunschmidt & Co. and Edward Barnard didn’t see eye to eye on certain matters,» he replied.

Bateman did not quite like the fellow’s manner, so he got up, not without dignity, and with an apology for troubling him bade him good-day. He left the place with a singular feeling that the man he had just interviewed had much to tell him, but no intention of telling it. He walked in the direction indicated and soon found himself at Cameron’s. It was a trader’s store, such as he had passed half a dozen of on his way, and when he entered the first person he saw, in his shirt sleeves, measuring out a length of trade cotton, was Edward. It gave him a start to see him engaged in so humble an occupation. But he had scarcely appeared when Edward, looking up, caught sight of him, and gave a joyful cry of surprise.

«Bateman! Who ever thought of seeing you here?»

He stretched his arm across the counter and wrung Bateman’s hand. There was no self-consciousness in his manner and the embarrassment was all on Bateman’s side.

«Just wait till I’ve wrapped this package.»

With perfect assurance he ran his scissors across the stuff, folded it, made it into a parcel, and handed it to the dark-skinned customer.

«Pay at the desk, please.»

Then, smiling, with bright eyes, he turned to Bateman.

«How did you show up here? Gee, I am delighted to see you. Sit down, old man. Make yourself at home.»

«We can’t talk here. Come along to my hotel. I suppose you can get away?»

This he added with some apprehension.

«Of course I can get away. We’re not so businesslike as all that in Tahiti.» He called out to a Chinese who was standing behind the opposite counter. «Ah-Ling, when the boss comes tell him a friend of mine’s just arrived from America and I’ve gone out to have a drain with him.»

«All-light,» said the Chinese, with a grin.

Edward slipped on a coat and, putting on his hat, accompanied Bateman out of the store. Bateman attempted to put the matter facetiously.

«I didn’t expect to find you selling three and a half yards of rotten cotton to a greasy nigger,» he laughed.

«Braunschmidt fired me, you know, and I thought that would do as well as anything else.»

Edward’s candour seemed to Bateman very surprising, but he thought it indiscreet to pursue the subject.

«I guess you won’t make a fortune where you are,» he answered, somewhat dryly.

«I guess not. But I earn enough to keep body and soul together, and I’m quite satisfied with that.»

«You wouldn’t have been two years ago.»

«We grow wiser as we grow older,» retorted Edward, gaily.

Bateman took a glance at him. Edward was dressed in a suit of shabby white ducks, none too clean, and a large straw hat of native make. He was thinner than he had been, deeply burned by the sun, and he was certainly better looking than ever. But there was something in his appearance that disconcerted Bateman. He walked with a new jauntiness; there was a carelessness in his demeanour, a gaiety about nothing in particular, which Bateman could not precisely blame, but which exceedingly puzzled him.

«I’m blest if I can see what he’s got to be so darned cheerful about,» he said to himself.

They arrived at the hotel and sat on the terrace. A Chinese boy brought them cocktails. Edward was most anxious to hear all the news of Chicago and bombarded his friend with eager questions. His interest was natural and sincere. But the odd thing was that it seemed equally divided among a multitude of subjects. He was as eager to know how Bateman’s father was as what Isabel was doing. He talked of her without a shade of embarrassment, but she might just as well have been his sister as his promised wife; and before Bateman had done analysing the exact meaning of Edward’s remarks he found that the conversation had drifted to his own work and the buildings his father had lately erected. He was determined to bring the conversation back to Isabel and was looking for the occasion when he saw Edward wave his hand cordially. A man was advancing towards them on the terrace, but Bateman’s back was turned to him and he could not see him.