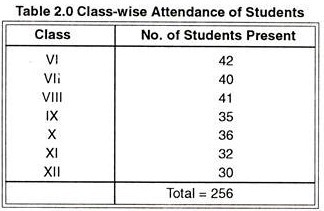

The upward slope of the labor supply curve shows that

The upward slope of the labor supply curve shows that

The upward slope of the labor supply curve shows that

The demand for labor is one determinant of the equilibrium wage and equilibrium quantity of labor in a perfectly competitive market. The supply of labor, of course, is the other.

Economists think of the supply of labor as a problem in which individuals weigh the opportunity cost of various activities that can fill an available amount of time and choose how to allocate it. Everyone has 24 hours in a day. There are lots of uses to which we can put our time: we can raise children, work, sleep, play, or participate in volunteer efforts. To simplify our analysis, let us assume that there are two ways in which an individual can spend his or her time: in work or in leisure. Leisure is a type of consumption good; individuals gain utility directly from it. Work provides income that, in turn, can be used to purchase goods and services that generate utility.

The more work a person does, the greater his or her income, but the smaller the amount of leisure time available. An individual who chooses more leisure time will earn less income than would otherwise be possible. There is thus a tradeoff between leisure and the income that can be earned from work. We can think of the supply of labor as the flip side of the demand for leisure. The more leisure people demand, the less labor they supply.

Income and Substitution Effects

Suppose wages rise. The higher wage increases the price of leisure. We saw in the module on consumer choice that consumers substitute more of other goods for a good whose price has risen. The substitution effect of a higher wage causes the consumer to substitute labor for leisure. To put it another way, the higher wage induces the individual to supply a greater quantity of labor.

Faced with the inequality above, an individual will give up some leisure time and spend more time working. As the individual does so, however, the marginal utility of the remaining leisure time rises and the marginal utility of the income earned will fall. The individual will continue to make the substitution until the two sides of the equation are again equal. For a worker, the substitution effect of a wage increase always reduces the amount of leisure time consumed and increases the amount of time spent working. A higher wage thus produces a positive substitution effect on labor supply.

But the higher wage also has an income effect. An increased wage means a higher income, and since leisure is a normal good, the quantity of leisure demanded will go up. And that means a reduction in the quantity of labor supplied.

For labor supply problems, then, the substitution effect is always positive; a higher wage induces a greater quantity of labor supplied. But the income effect is always negative; a higher wage implies a higher income, and a higher income implies a greater demand for leisure, and more leisure means a lower quantity of labor supplied. With the substitution and income effects working in opposite directions, it is not clear whether a wage increase will increase or decrease the quantity of labor supplied—or leave it unchanged.

Wage Changes and the Slope of the Supply Curve

What would any one individual’s supply curve for labor look like? One possibility is that over some range of labor hours supplied, the substitution effect will dominate. Because the marginal utility of leisure is relatively low when little labor is supplied (that is, when most time is devoted to leisure), it takes only a small increase in wages to induce the individual to substitute more labor for less leisure. Further, because few hours are worked, the income effect of those wage changes will be small.

It is possible that beyond some wage rate, the negative income effect of a wage increase could just offset the positive substitution effect; over that range, a higher wage would have no effect on the quantity of labor supplied. That possibility is illustrated between points B and C on the supply curve in Figure 12.7; Ms. Wilson’s supply curve is vertical. As wages continue to rise, the income effect becomes even stronger, and additional increases in the wage reduce the quantity of labor she supplies. The supply curve illustrated here bends backward beyond point C and thus assumes a negative slope. The supply curve for labor can thus slope upward over part of its range, become vertical, and then bend backward as the income effect of higher wages begins to dominate the substitution effect.

It is quite likely that some individuals have backward-bending supply curves for labor—beyond some point, a higher wage induces those individuals to work less, not more. However, supply curves for labor in specific labor markets are generally upward sloping. As wages in one industry rise relative to wages in other industries, workers shift their labor to the relatively high-wage one. An increased quantity of labor is supplied in that industry. While some exceptions have been found, the mobility of labor between competitive labor markets is likely to prevent the total number of hours worked from falling as the wage rate increases. Thus we shall assume that supply curves for labor in particular markets are upward sloping.

Shifts in Labor Supply

What events shift the supply curve for labor? People supply labor in order to increase their utility—just as they demand goods and services in order to increase their utility. The supply curve for labor will shift in response to changes in the same set of factors that shift demand curves for goods and services.

Changes in Preferences

A change in attitudes toward work and leisure can shift the supply curve for labor. If people decide they value leisure more highly, they will work fewer hours at each wage, and the supply curve for labor will shift to the left. If they decide they want more goods and services, the supply curve is likely to shift to the right.

Changes in Income

An increase in income will increase the demand for leisure, reducing the supply of labor. We must be careful here to distinguish movements along the supply curve from shifts of the supply curve itself. An income change resulting from a change in wages is shown by a movement along the curve; it produces the income and substitution effects we already discussed. But suppose income is from some other source: a person marries and has access to a spouse’s income, or receives an inheritance, or wins a lottery. Those nonlabor increases in income are likely to reduce the supply of labor, thereby shifting the supply curve for labor of the recipients to the left.

Changes in the Prices of Related Goods and Services

Several goods and services are complements of labor. If the cost of child care (a complement to work effort) falls, for example, it becomes cheaper for workers to go to work, and the supply of labor tends to increase. If recreational activities (which are a substitute for work effort) become much cheaper, individuals might choose to consume more leisure time and supply less labor.

Changes in Population

An increase in population increases the supply of labor; a reduction lowers it. Labor organizations have generally opposed increases in immigration because their leaders fear that the increased number of workers will shift the supply curve for labor to the right and put downward pressure on wages.

Changes in Expectations

One change in expectations that could have an effect on labor supply is life expectancy. Another is confidence in the availability of Social Security. Suppose, for example, that people expect to live longer yet become less optimistic about their likely benefits from Social Security. That could induce an increase in labor supply.

Labor Supply in Specific Markets

The supply of labor in particular markets could be affected by changes in any of the variables we have already examined—changes in preferences, incomes, prices of related goods and services, population, and expectations. In addition to these variables that affect the supply of labor in general, there are changes that could affect supply in specific labor markets.

A change in wages in related occupations could affect supply in another. A sharp reduction in the wages of surgeons, for example, could induce more physicians to specialize in, say, family practice, increasing the supply of doctors in that field. Improved job opportunities for women in other fields appear to have decreased the supply of nurses, shifting the supply curve for nurses to the left.

The supply of labor in a particular market could also shift because of a change in entry requirements. Most states, for example, require barbers and beauticians to obtain training before entering the profession. Elimination of such requirements would increase the supply of these workers. Financial planners have, in recent years, sought the introduction of tougher licensing requirements, which would reduce the supply of financial planners.

Worker preferences regarding specific occupations can also affect labor supply. A reduction in willingness to take risks could lower the supply of labor available for risky occupations such as farm work (the most dangerous work in the United States), law enforcement, and fire fighting. An increased desire to work with children could raise the supply of child-care workers, elementary school teachers, and pediatricians.

The Supply Curve of Labour (Explained With Diagram)

The Supply Curve of Labour!

It is important to know how many hours a worker will be willing to work at different wage rates. When the real wage rate increases, the individual will be pulled in two opposite directions. The real wage rate is the relative price of leisure which has to be given up for doing work to earn income.

As real wage rate rises, leisure becomes relatively more expensive (in terms of income foregone) and this induces the individual to substitute work (or income) for leisure. This is called substitution effect of the rise in real wage and induces the individual to work more hours (i.e. supply more labour) to earn more income.

But the increase in the real wage rate also makes the individual richer, that is, his income increases. This increase in income tends to make the individual to consume more of all commodities including leisure. This is called income effect of the rise in wage rate which tends to increase leisure and reduce number of work hours (i.e. reduce labour supply. The economists generally believe that substitution effect of a rise in real wage is larger than its income effect and therefore individuals work for more hours (that is, supply more labour) at a higher wage rate.

However, beyond a certain higher real wage and number of hours worked, leisure becomes more desirable and income effect outweighs substitution effect, and as a result supply of labour decreases beyond a certain higher wage rate.

In what follows we shall explain how we derive a supply curve of labour of an individual and of the economy as a whole in all these circumstances. Thus, whether an individual will supply more work- effort or less as a result of the rise in the wage rate depends upon the relative strengths of the income and substitution effects.

The changes in the work-effort or labour supplied by an individual worker due to the changes in the wage rate is illustrated in Fig. 33.1(a) To begin with, the wage line is AW1 the slope of the wage line indicates the wage rate per hour.

With wage line AW1, the individual is in equilibrium at point Q on indifference curve I1 and is working AL1 hours in a week. Suppose the wage rate rises so that the new wage line is AW2 with wage line AW2, the individual is in equilibrium at point R on the indifference curve I2, and is now working AL2 hours which are more than before.

If the wage rate further rises so that the new wage line is AW3, the individual moves to the point S on indifference curve I3 and works AL3 hours which are more than AL1 or AL2. Suppose the wage rate further rises so that the wage line is AW4. With wage line AW4, the individual is in equilibrium at point T and works AL4 hours.

If points Q, R, S and Tare connected, we get what is called wage offer curve which shows the number of hours that an individual offers to work at various wage rates. It should be noted that the wage offer curve, strictly speaking, is not the supply curve of labour though it provides the same information as the supply curve of labour.

The supply curve of labour is obtained when the wage rate is directly represented on the Y-axis and labour (i.e. work effort) supplied at various w age rates on the X-axis reading from left to right. In Fig. 33.2 the supply curve of labour has been drawn from the information gained from Fig. 33.1. Let the wage line AW1 represent the wage rate equal to P1, wage line AW2 represents wage rate P2, wage line AW3 represents wage rate P3 and wage line AW4 represent wage rate P4. It will be seen that as the wage rate rises from P1 to P4 and as a result the wage line shifts from AW1 to AW4 the number of hours worked, that is, the amount of labour supplied increases from AL1 to AL4.

As a result, the supply curve of labour in Fig. 33.2 is upward sloping. The indifference map depicted in Fig. 33.1 is such that the substitution effect of the rise in the wage rate is stronger than the income effect of the rise in the wage rate so that the work- effort supplied increases as the wage rate rises.

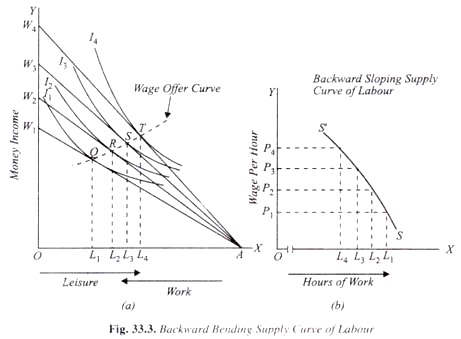

Backward-Sloping Supply Curve of Labour:

But the supply curve of labour is not always upward sloping. When an individual prefers leisure to income, then the supply of labour (number of hours worked) by an individual will decrease as the wage rate rises. This is because in such a case income effect which tends to reduce the work effort outweighs the substitution effect which tends to increase the work effort.

In Fig. 33.3 such an indifference map is shown which yields a backward sloping supply curve of labour which indicates that the number of hours worked per week decreases as the wage rate rises. AW1, AW2, AW3 and AW4 are the wage lines when the wages rates are P1, P2, P3 and P4 respectively.

Q, R, S and Tare the equilibrium points with the wage lines AW1, AW2, AW3 and AW4 respectively. It will be noticed from Fig. 33.3(a) that when the wage rate rises and as a consequence the wage line shifts from AW1 to AW4 the number of hours worked per week decreases from AL1 to AL4.

In Fig. 33.3(b) supply curve of labour is drawn with K-axis representing the hourly wage rate and X-axis representing number of hours worked per week at various wage rates. It will be seen from Fig. 33.3(b) as the wage rate rises from P1 to P4 the supply of labour (i.e., number of hours worked per week) decreases from OL1 to OL4. In other words, the supply curve of labour slopes backward, that is, slopes upward from right to left. It should be noted that it is the nature or pattern of indifference curves between income and leisure that yields backward sloping supply curve.

A glance at Fig. 33.3(a) and Fig. 33.3(b) will reveal that the nature of indifference curves in the two is different. As said above, the nature of indifference curves depend upon the relative preference between income and leisure.

In Fig. 33.3(a) indifference curves between income and leisure are such that the individual’s preference for leisure is relatively greater than for income. In this case, when the wage rate rises the individual enjoys more leisure and accordingly reduces the number of hours worked per week.

But it sometimes happens that as the hourly wage rate rises from a very low level to a reasonably good level, the number of hours worked per week rises and as the hourly wage rate rises further, the number of hours worked per week decreases.

This may be the case of an individual who has some more or less fixed minimum wants for goods and services which he can satisfy with a certain money income. When the wage rate is so low that he is not earning sufficient money income, then to satisfy his more or less fixed minimum wants for goods and services, his preference for income will be relatively greater than that for leisure and, therefore, when the wage rate rises the individual will work more hours per week.

When the wage rate has risen to a level which is sufficient to yield a sufficient money income for satisfying his fixed minimum wants, then for further increases in wage rate the number of hours worked per week will decrease because now the individual can afford to have more leisure and also earn an income sufficient to meet his minimum wants for goods and services.

It follows from above that up to a certain wage rate the supply curve will slope upward from left to right and then for further increases in the wage rate the supply curve of labour will slope backward.

In Fig. 33.4(a) an indifference map along with a set of wage lines AW1, AW2, AW3 and AW4 (showing wage rates P1, P2, P3, P4 respectively) are shown. As the wage rate rises to P2 and hence the wage line shifts to AW2 the number of hours worked by the individual per week increases but when the wage rate further rises to P3 and P4 and hence the wage line shifts to AW3 and AW4, the number of hours worked by the individual decreases. From Fig. 33.4(b) it will be explicitly seen that the supply curve of labour slopes upward to the wage rate P2 (that is, point K) and beyond that it slopes backward.

Supply Curve of Labour for the Economy as a Whole:

The supply curve of labour of a group of individuals or of the whole working force in the economy can be derived by summing up horizontally the supply curves of individuals. It may be noted that the supply curve of labour for the economy as a whole will be upward sloping or backward sloping depending upon whether the relative number of individuals having upward sloping supply curves is greater or less than those having backward sloping supply curves of labour. Further, different individuals will have backward sloping portion in their supply curve at different wage ranges, which creates difficulties in finding the nature of supply curve of the whole work force.

It is generally found that when the wage rate rises from the initially low level to a sufficiently good level, the total supply of labour to the economy as a whole increases (that is, supply curve for the economy as a whole slopes upward to a certain wage rate) and for further increases in the wage rate, the total supply of labour to the economy as a whole decreases (that is, beyond a certain wage rate the total supply curve of labour slopes backward). Thus, the total supply curve of labour for the economy as a whole is generally believed to be the shape depicted in Fig. 33.3(b).

The Aggregate-Supply Curve

Why the Aggregate-Supply Curve Slopes Upward in the Short Run

The key difference between the economy in the short run and in the long run is the behavior of aggregate supply.

The long-run aggregate-supply curve is vertical because, in the long run, the overall level of prices does not affect the economy’s ability to produce goods and services. By contrast, in the short run, the price level does affect the economy’s output.

That is, over a period of a year or two, an increase in the overall level of prices in the economy tends to raise the quantity of goods and services supplied, and a decrease in the level of prices tends to reduce the quantity of goods and services supplied.

As a result, the short-run aggregate-supply curve slopes upward, as shown in Figure I.

The following theories differ in their details, but they share a common theme: The quantity of output supplied deviates from its long-run, or natural, level when the actual price level in the economy deviates from the price level that people expected to prevail.

When price level rises above the level that people expected, output rises above its natural level, and when the price level falls below the expected level, output falls below its natural level.

The Sticky-Wage Theory

This theory is the simplest of the three approaches to aggregate supply, and some economists believe it highlights the most important reason why the economy in the short run differs from the economy in the long run. Therefore, it is the theory of short-run aggregate supply that we emphasize in the series.

To some extent, the show adjustment of nominal wages is attributable to long-term contracts between workers and firms that fix nominal wages, sometimes for as long as 3 years. In addition, this prolonged adjustment may be attributable to slowly changing social norms and notions of fairness that influence wage setting.

Over time, the labor contracts will expire, and the firm can negotiate with its workers for a lower wage (which they may accept because prices are lower), but in the meantime, employment and production will remain below their long-run levels.

Eventually, the workers will demand higher nominal wages to compensate for the higher price level, but for a while, the firm can take advantage of the profit opportunity by increasing employment and production above their long-run levels.

This stickiness of wages gives firms an incentive to produce less output when the price level turns out lower than expected and to produce more when the price level turns out higher than expected.

The Sticky-Price Theory

The sticky-price theory emphasizes that the prices of some goods and services also adjust sluggishly in response to changing economic conditions.

Although some firms reduce their prices quickly in response to the unexpected change in economic conditions, many other firms want to avoid additional menu costs. As a result, they temporarily lag behind in cutting their prices.

Because these lagging firms have prices that are too high, their sales decline. Declining sales, in turn, cause these firms to cut back on production and employment.

In other words, because not all prices adjust immediately to changing conditions, an unexpected fall in the price level leaves some firms with higher-than-desired prices, and these higher-than-desired prices depress sales and induce firms to reduce the quantity of goods and services they produce.

Similar reasoning applies when the money supply and price level turn out to be above what firms expected when they originally set their prices.

While some firms raise their prices quickly in response to the new economic environment, other firms lag behind, keeping their prices at the lower-than-desired levels.

These low prices attract customers, which induces these firms to increase employment and production.

The Misperceptions Theory

To see how this might work, suppose the overall price level falls below the level that suppliers expected.

For example, wheat farmers may notice a fall in the price of wheat before they notice a fall in the prices of the many items they buy as consumers. They may infer from this observation that the reward for producing wheat is temporarily low, and they may respond by reducing the quantity of wheat they supply.

Similarly, workers may notice a fall in their nominal wages before they notice that the prices of the goods they buy are also falling.

They may infer that the reward for working is temporarily low and respond by reducing the quantity of labor they supply.

In both cases, a lower price level causes misperceptions about relative prices, and these misperceptions induce suppliers to respond to the lower price level by decreasing the quantity of goods and services supplied.

Suppliers of goods and services may notice the price of their output rising and infer, mistakenly, that their relative prices are rising.

Summing Up

There are three alternative explanations for the upward slope of the short-run aggregate-supply curve :

Economists debate which of these theories is correct, and it is possible that each contains an element of truth. For our purpose, the similarities of the theories are more important than the differences.

All three theories suggest that output deviates in the short run from its natural level when the actual price level deviates from the price level that people had expected to prevail.

In the long run, it is reasonable to assume that wages and prices are flexible rather than sticky and that people are not confused about relative prices. Thus, while we have several good theories to explain why the short-run aggregate-supply curve slopes upward, they are all consistent with a long-run aggregate-supply curve that is vertical.

Why the Short-run Aggregate Supply Curve is Upward Sloping

By Raphael Cedar | Updated Jun 26, 2020 (Published Feb 29, 2020)

According to classical macroeconomic theory, the aggregate supply curve is perfectly vertical in the long run. However, in the short term (i.e., over a period of one or two years), it is upward sloping. That means a decrease in the overall price level results in a lower quantity of goods and services supplied and vice versa. There are three theories that try to explain why suppliers behave differently in the short run than they do in the long run: (1) the sticky wage theory, (2) the sticky price theory, and (3) the misperceptions theory. We will look at each of them in more detail below.

1. The Sticky Wage Theory

According to the sticky wage theory, the upward slope of the aggregate supply curve in the short-run is due to the fact that nominal wages are slow to adjust to changes in the overall price level (i.e., they are sticky). That means when the price level falls, most firms cannot adjust wages immediately, which leads to an increase in real production costs. As a consequence, the suppliers hire fewer workers and produce a smaller quantity of goods and services. According to this theory, the slow adjustment rate of wages is mainly caused by existing employment contracts and social norms that prevent frequent wage cuts.

For example, think of an imaginary firm that employs several workers. All of those employees have long-term contracts, and the firm has agreed to pay them a nominal wage based on the expected price level. Now, if the price level falls below the expected level, the firm’s real wages (i.e., nominal wages/price level) increase, which results in higher real costs. Meanwhile, revenue is likely to decrease due to the unexpectedly low price level. As a result, the firm hires fewer workers to cut costs and produces a smaller quantity output.

2. The Sticky Price Theory

The sticky price theory states that the short-run aggregate supply curve slopes upward because the prices of some goods and services are slow to adjust to changes in the overall price level. That means when the overall price level falls, some firms may find it hard to adjust the prices of their products immediately. This causes sales to drop, which in turn leads to a decrease in the quantity of goods and services supplied. According to the sticky price theory, the primary reason for sticky prices is what we call menu costs. Menu costs describe all costs incurred by firms in order to change their prices (e.g., printing new menus, distributing updated price lists, changing price tags on the shelves).

To illustrate this, imagine all firms announce their prices at the beginning of the year, based on the overall price level they expect. Then, throughout the year, the actual price level falls lower than expected. In reaction to this, some firms immediately lower their prices, while others decide to temporarily stick with their initial prices to avoid additional menu costs. In other words, they don’t want to (or can’t afford to) spend money on new brochures, price lists, menus, etc. As a result, their prices are now too high, and sales decline. This, in turn, causes them to temporarily reduce production and hire fewer workers.

3. The Misperceptions Theory

According to the misperceptions theory, the short-run aggregate supply curve is upward sloping because changes in the overall price level can temporarily mislead suppliers about what is happening in their individual market. That means, when the price level falls, many firms will notice a fall in the price of the goods and services they sell and reduce production because they believe their business has become less profitable. However, if the overall price level falls, the prices of other products (including raw materials used for production) decrease as well. That means the relative price of the firms’ products doesn’t necessarily decline, and there is no actual reason to reduce the output.

To give an example, think of a firm that sells mobile phones. If the overall price level falls, the managers of this firm may notice a fall in the prices of mobile phones. Based on this observation, they may mistakenly believe that their business has become less profitable (i.e., their relative prices have fallen) and temporarily cut back on production and employment. Meanwhile, however, the prices of input materials have declined as well, so the relative price of mobile phones hasn’t changed, and their fear was unfounded.

Summary

While the aggregate supply curve is perfectly vertical in the long run, it is upward sloping in the short run. There are three theories that try to explain why suppliers behave differently in the short run than they do in the long run: the sticky wage theory, the sticky price theory, and the misperceptions theory. According to the sticky wage theory, the upward slope of the short-run aggregate supply curve is due to the fact that nominal wages are slow to adjust to changes in the overall price level. The sticky price theory states that the curve slopes upward because the prices of some goods and services are slow to adjust to changes in the price level. Finally, the misperceptions theory states that the short-run aggregate supply curve is upward sloping because changes in the overall price level can temporarily mislead suppliers about what is happening in their individual market.

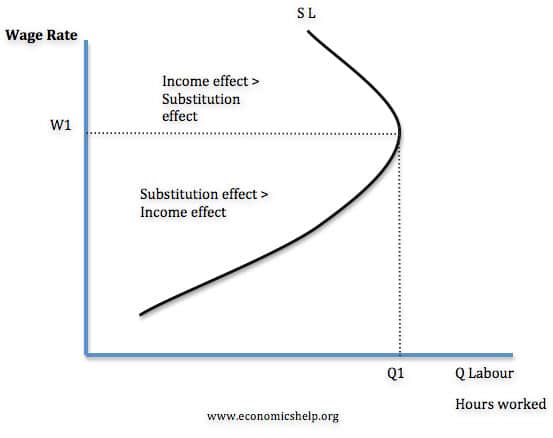

Backward Bending Supply Curve

A typical supply curve shows an increase in supply as wages rise. It slopes from left to right.

However, in labour markets, we can often witness a backward bending supply curve. This means after a certain point, higher wages can lead to a decline in labour supply. This occurs when higher wages encourage workers to work less and enjoy more leisure time.

Diagram of Backward Bending Supply Curve

There are two effects related to determining supply of labour.

When does the labour curve begin to slope backwards?

It will depend on an individual:

Other factors affecting labour supply

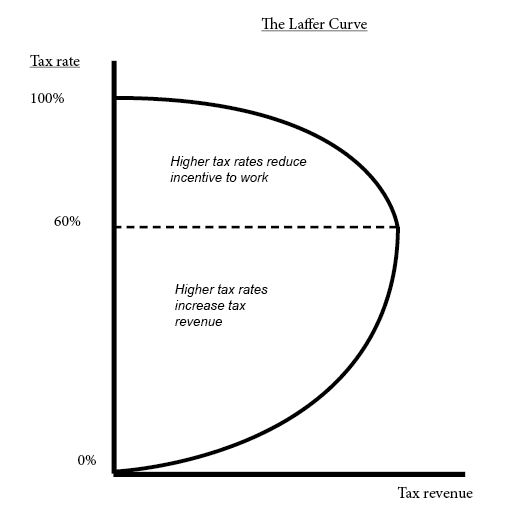

Backward bending supply curve and the Laffer curve

The backward bending supply curve has implications for tax policy.

Empirical studies on the backward bending supply curve

An investigation into the Canadian Labour market found empirical evidence of a backward supply curve for labour, especially amongst female workers.

The study also found

Related

References

Rahman, Adib J. (2013) “An econometric analysis of the “backward-bending” labour supply of Canadian women,” Undergraduate Economic Review: Vol. 10: Iss. 1, Article 6.

3 thoughts on “Backward Bending Supply Curve”

Can you please briefly explain leisure time and human factor in this graph

Supposed that in a monopoly union framework, the union maximize it’s wage bill and a straight line can approximate the firm labour demand curve

a) What happens to the level of employment and the wage paid if demand in the product market increases? what happens to profit?

Why ppc is backward bending

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Recent Posts

Selected Posts

Random Glossary term

Ask an economics question

You are welcome to ask any questions on Economics.

About

Tejvan Pettinger studied PPE at LMH, Oxford University. Find out more

We use cookies on our website to collect relevant data to enhance your visit.

Our partners, such as Google use cookies for ad personalization and measurement. See also: Google’s Privacy and Terms site

By clicking “Accept All”, you consent to the use of ALL the cookies. However, you may visit «Cookie Settings» to provide a controlled consent.

You can read more at our privacy page, where you can change preferences whenever you wish.

Источники информации:

- http://www.yourarticlelibrary.com/economics/supply-curve/the-supply-curve-of-labour-explained-with-diagram/37466

- http://www.ifioque.com/library/framework-for-short-run-analysis

- http://quickonomics.com/why-the-short-run-aggregate-supply-curve-is-upward-sloping/

- http://www.economicshelp.org/blog/glossary/backward-bending-supply/