What animal is pounding mochi on the moon

What animal is pounding mochi on the moon

Chapter 2: Mystic Lake

Mystic Lake is the second chapter of the game. It hosts Room 26 to Room 50 as well as two secret rooms in UDG2. This chapter was released on 17th October 2021. Chapter 2 is the second easiest chapter in the game with its difficulty being in Difficulty 1.0 to Difficulty 2.0 range. However, many still struggle in this chapter due to the big gap of thinking required in these rooms compared to Chapter 1.

Chapter 2 is also the first chapter to introduce Sub-Chapters; two of them which are Deep Forest and The Crossing. It is also the first chapter to include two secret rooms. One of them being a Teamwork categorized room.

Contents

Design

Chapter 2 is placed on a grassy area with a big lake in the middle as well as a waterfall. It starts at the south side of the area and ends at the north east side also known as Pifa Town (Room 51). The first half of rooms in Chapter 2 are on land while the other half are on water (above the lake). The area on land includes many places which are Mystic Lake Elementary School (Room 29), Mystic Lake Fair (Room 31), Deep Forest (Sub-Chapter), Renovated Rustic Home (Room 40) and a pier (Room 50). The lake consists of a bridge from that connects the west and east side of the lake.

Deep Forest

Deep Forest is an area on the west side of Mystic Lake. It holds rooms Room 34 to Room 40. The area is detailed on an elevated ground with different colored trees, bushes and grass ranging from a light green to a moderate brown. Certain rooms are decorated to fit its area such as Room 35 and Room 37 where they are detailed as logs, Room 40 being the house and gate to The Crossing and Room 34 being located in a small cave. There also lies a small signboard which displays «Error 404».

The Crossing

The Crossing is a bridge that connects the west and east side of the lake. It holds rooms Room 41 to Room 49. The Crossing includes some places such as Wipeout Obby (Room 43) and CodeHelperBrick’s Boat Hire (Room 45). In Room 45, the player travels through the lake by a boat. This created a tiny open area exploration and is used as the entrance to enter Secret III.

Mechanics

This chapter introduces 2 new mechanics towards players who have progressed through 2/10 of the game. Those are as follows:

Pushbox

Introduced before entering Mystic Lake (Room 26). It is considered that this mechanic will be used in future rooms in future chapters. The first room to use this mechanic being at Room 37.

Room Info Board

Introduced after the Pushbox tutorial. These boards are used to reveal each room’s difficulty and their category. Starting from Chapter 2, room info boards will be used for the rest of the future rooms.

Rooms

Pushbox Mechanic & Room Info Board introduced

First Room of Sub-Chapter 2.1

Last Room of Sub-Chapter 2.1

First Room of Sub-Chapter 2.2

Last Room of Sub-Chapter 2.2

Soundtrack

There are a total of 9 songs used alongside 3 replaced in Chapter 2. They are:

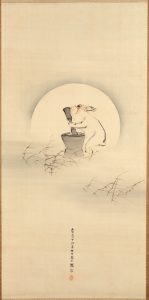

New Orleans Museum of Art

Mori Ippo (Japanese, 1798–1871), Rabbit Pounding the Elixir of Life Under the Moon, 1867, Ink and light color on silk, 40 1/2 x 20 in., Museum purchase, Friends of Asian Art, 92.20

Rising above a minimal landscape of reeds and clouds, a rabbit is silhouetted against the moon, busy at work using a mortar and pestle. In Japanese folklore, a mystical hare who inhabits the moon mashes ingredients for mochi, a traditional rice-flour cake. Japanese artist Mori Ippo (1798–1871) used ink and light color on silk to create this auspicious image associated with the celebration of a new year.

The tradition of making mochi originated in China thousands of years ago. By the Heian period in Japan (794–1192) it was well-established and considered to be a food closely associated with the divine, made both as an offering to the gods and for consumption by pilgrims at temples and shrines. Shops offering mochi would often be found near sites of worship, and a number still exist, some having sold these treats for more than a thousand years. One such is Ichiwa, a Kyoto-based mochi seller recently profiled in the New York Times.

Mochi-making is closely associated with the turn of a new year. The pounding of the rice and creation of these delicacies is a treasured family- and community-based culinary custom in Japan, with individuals taking turns at pounding sweetened, cooked rice into a smooth, pliable consistency. (Watch a YouTube video of rice pounding and the making of the mochi.)

Ippo was heir to a tradition of naturalistic animal painting in Osaka during the late Edo and early Meiji periods (mid-eighteenth through nineteenth centuries). His teacher, Mori Tetsuzan (1775–1841), was a son of the tradition’s founder, Mori Sosen (1747–1821), who was renowned for his depictions of the native Japanese macaque. Ippo married Tetsuzan’s daughter and was formally adopted into the Mori family, taking the family name. A well-regarded painter of landscapes, birds, and animal subjects, Ippo headed the Mori school in Osaka after his adopted father’s death.

–Lisa Rotondo-McCord, Deputy Director for Curatorial Affairs/Curator of Asian Art

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. Your gift will make a direct and immediate impact as NOMA welcomes our community back to the museum and sculpture garden, plans new exhibitions, and develops virtual and at-home arts education resources for school partners.

Original Version Unavailable

Songs & Rhymes From

Original Version Unavailable

Original Version Unavailable

If anyone can provide a copy of the original

song, please email me.

(English)

If anyone can provide a copy of the original

song, please email me.

Original Version Unavailable

(English)

If anyone can provide a copy of the original

song, please email me.

If anyone can provide a copy of the original

song, please email me.

Mama Lisa’s Books

Our books feature songs in the original languages, with translations into English. Many include beautiful illustrations, commentary by ordinary people, and links to recordings, videos, and sheet music. Your purchase will help us keep our site online!

Favorite Kids Songs

A Mama Lisa eBook

Over 50 Favorites (150+ Pages)

Many with Sheet Music and Links to Recordings!

You’ll find over 50 English language kids songs, including:

—Hot Cross Buns

—I’ve Been Working On The Railroad

—Down By The Bay

—Make New Friends

—Mama’s Gonna Buy You A Mockingbird

—Ring-A-Round The Rosie

—Lavender’s Blue

—Five Little Monkeys

And many more!

THIS IS A DOWNLOADABLE EBOOK AVAILABLE INSTANTLY.

Sing Your Kids To Sleep

Over 50 lullabies and recordings from all over the world. Each Lullaby includes the full text in the original language, with an English translation.

THIS IS A DOWNLOADABLE EBOOK AVAILABLE INSTANTLY.

Lyrics & Recordings Needed!

Please contribute a traditional song or rhyme from your country.

Christmas Carols Around The World

More Songs From

More s From Around The World

Songs in the Language

Articles about

Countries and Cultures in

Songs by Continent

Songs With Many Versions Around The World

Lyrics & Recordings Needed!

Mama Lisa’s Blog

Music, culture and traditions from all around the world!

Mama Lisa’s Blog

Music, culture and traditions from all around the world!

100 Songs (350 Pages) With Sheet Music And Links To Recordings

We’ve gathered 100 of our favorite songs and rhymes from all the continents of the globe. (Over 350 pages!)

Each song includes the full text in the original language, with an English translation, and most include sheet music.

All include links to web pages where you can listen to recordings, hear the tune or watch a video performance.

Each includes a beautiful illustration. Many have commentary sent to us by our correspondents who write about the history of the songs and what they’ve meant in their lives.

We hope this book will help foster a love of international children’s songs!

THIS IS A DOWNLOADABLE EBOOK AVAILABLE INSTANTLY.

How To Make Mochi (お餅) at Home

Published January 3, 2021 / Last modified January 3, 2021 By Shihoko | Chopstick Chronicles / Leave a Comment

I’m sure most people have heard of Mochi by now since it has become so popular worldwide. There’s a very clear reason why it’s so popular – because it’s so delicious! The simple and subdued flavour of mochi as well as its squishy soft texture make it compatible with nearly anything. You may have seen it most often wrapped around ice cream but in Japan it has many more uses in dishes, sweets, and traditions.

Table of contents

What is Mochi?

Mochi is a Japanese rice cake made from Mochigome short-grain japonica glutinous rice, also known as sweet rice. It has been indispensable since ancient times in Japan at festivals as an offering of food for the gods, along with sake.

Why You Will Love This Mochi Recipe?

Special Ingredient Note

For making mochi, we need to use special rice called “Mochigome (mochi rice)” which is also known as sweet rice. It is short-grain Japonica glutinous rice. It is different from ordinary rice that is usually eaten as steamed rice with dishes such as Japanese curry rice. Comparing those two different type of rice – ordinary rice, which is called Uruchimai (Uruchi rice) is translucent whereas the glutinous rice is white and opaque. But the big difference is the type of starch it contains. Ordinary rice contains amylose and amylopectin but glutinous contains amylopectin only that makes the glutinous rice really sticky. Reference: The difference between mochigome & uruchimai

Where To Buy Glutinous Rice?

Glutinous rice is widely distributed in Southeast Asia and East Asia including Japan, where there is a habit of eating glutinous rice. So it is available from Japanese or Asian grocery stores. If you cannot access those grocery stores, It is available from online stores. Have a look at Chopstick Chronicles’ Amazon shop front.

How Japanese Mochi Is Made?

Japanese mochi is typically made in two days. On day one, wash the rice and let it soak overnight. If you are going to make mochi in the traditional Japanese way, you need a wooden mortar and wooden pestles. Those Mochitsuki (glutinous rice pounding) pieces of equipment need to be soaked in water too to prevent the wooden equipment from cracking or the rice sticking to the equipment. On the second day, steam the rice and pound the mochi dough. Then shape the dough while it is hot.

How to Steam Glutinous Rice?

Traditional method with a Bamboo Steamer – line the steamer bottom with a tightly squeezed wet kitchen cloth. Drain the water and spread the rice over the lined steamer. Place the steamer over a pot of boiling water and steam it for 30-45 minutes. Instant pot – Add 2 cups of water in your instant pot and place steaming trivet provided with instant pot inside the inner pot. Place a bowl, lined with a tightly squeezed wet cloth with rice over it, on top of the trivet. Put the lid on making sure the steam releasing valve is in the sealing position. Press the “Steam” function button and set 45 minutes. Rice Cooker – Some rice cookers have a special function to cook sweet rice to make Sekihan or rice with other grains. Add the same amount of water as rice and follow your rice cooker’s instructions.

Which Method To Pound The Mochi Dough?

Traditional method with wooden mortar and pestle – Discard the soaking water that you prepared the night before and fill the mortar with hot water while the rice is being steamed. Once the rice is steamed, empty the hot water which warmed the mortar, and place the steamed glutinous rice into the mortar. Using your body weight, press down on the rice with the pestle. Keep pounding the rice shifting and turning around with wet hands to pound evenly. When the mochi dough becomes a smooth texture, it is done.

Bread Machine & Stand Mixer – I used my bread machine’s kneading function. Steam the rice using whichever of the above methods, place the steamed rice into the machine, put lid on and press knead and set for 15-20 minutes.

How to Serve Mochi?

Freshly made mochi is so delicious served up on its own. You can dip the mochi into sugary soy powder (Kinako) or you can serve it with grated Daikon and soy sauce. Also, accompany with Anko sweet azuki bean paste or wrap a ball of sweet red bean paste with mochi. They are all good to serve with Hojicha and Matcha Latte too.

Kagami Mochi For New Years

Kagami mochi is two-tiered large and small round rice cakes decorated with bitter orange. Often made for a deity offering of new years. It is said that the round-shaped rice cake resembles a bronze mirror, which ancient Japanese believed the God dwelled in. Also, the round shape represents family harmony. Furthermore, the two-tiered appearance means to pile up fortune and grow older peacefully and the large and small sizes represent the moon and the sun, yin and yang.

Tips & Tricks

How to Store Mochi?

Mochi does not contain anything but glutinous rice (mochigome), so it becomes hard. If you make small round mochi, wrap them individually with cling wrap when it cools down. Place them in a ziplock bag and keep them in the freezer. It will keep for a month. You can toast them from frozen to eat. If you did not shape it and just left as a big batch, then the next day when it is still not completely dried out, slice them about 0.4inch (1cm) thick and then individually wrap with cling wrap and keep them in the ziplock bag in the freezer.

Indigo Days

Thoughts from an organic farm in rural Japan.

February 05, 2010

Pounding Mochi

“Gacha-gacha-gacha,” our monstrously heavy, and equally ancient front door rattles on its metal track, quickly followed by the whoosh of the wood and glass shoji inner front door. From the energy burst of the opening and the splash of hand washing, I know it’s Tadaaki, coming in for breakfast after collecting the early morning eggs. As he bangs brass against iron, I hear him hefting the antique stockpot onto our stove. He sparks the flame and the soft hum of the hood fan revs up. Christmas has come and gone, and now shogatsu (Japanese New Year) has arrived. I’m glad it’s Tadaaki’s turn to be in charge because I have no more energy left and burrow deeper into my down covers staving off the inevitable.

Shogatsu is traditionally a family time, though that has been waning in recent years as families disperse to far cities. But our family still follows most of the traditional practices.

Each year on the 29 th of December, Tadaaki washes the organic glutinous rice called mochi gome that we will pound the next day. This year Tadaaki plans to pound eight batches of mochi, so has eight pails of rice to wash and soak. Each pail holds three kilos of rice that he has bought from our grower friend, Suka-san. A couple years ago, Tadaaki discovered an antique rice washer upstairs in my collection of flea market finds and was excited to put it to use. The guy I bought it from said it was an ice cream maker. I doubted that, but was attracted by the fine craftsmanship of the old wooden bucket and the low price (sad but typical). Tadaaki soaks the rice overnight and the next morning we kick off shogatsu with a half-day of mochi making (mochi tsuki).

Every year, we do mochi tsuki outside in the garden and by some stroke of luck, that day almost always dawns sunny. Tadaaki wraps a pail of soaked mochi gome in a muslin cloth, puts the muslin bundle into a bamboo-steaming basket with a lid, and places it in an iron pot full of boiling water set over a wood burning fire. The glutinous rice steams for about an hour, then is plucked out of the steamer and dumped into a one meter “square,” hollowed out tree stump (usu) that Tadaaki has soaked over night. Tadaaki’s mother prepares a bucket of cold water next to the usu for dipping in the mallet or hands before touching the sticky rice. First Tadaaki circles the usu, smashing the rice grains with an oversized wooden mallet. Then he wields the mallet high above his head and pounds the mass with a series of distinctively satisfying “thumps.” The untutored tend toward squelchy, weak burps as their mallet lands on the rice. (They probably don’t reach far enough over their head to really get the necessary leverage.) One person pounds and another person dips his hand in the cold water, then folds the rice «dough» over itself in one quick movement in between the mallet contacting with the rice (almost like kneading bread). We invite a dozen or so friends and everyone gets a turn at pounding the mochi. In the past, Tadaaki and his brothers worked up a sweat, but now that the kids are getting bigger, and friends have gotten more skillful, so the mallet gets passed around and mochi tsuki is truly a community event.

As soon as each batch of mochi is pounded, we must work quickly before it cools to an unpliable mass. We smooth the hot mochi into half moon-shaped dumplings called kagami mochi that will be stacked up and offered to the house gods. Tadaaki continues to pinch off misshapen globs of mochi, as we flatten them into rough circles and stretch them around a ball of anko (simmered organic azuki beans smashed with organic sugar and a little sea salt). As more batches of mochi are pounded out, I take my turn at rolling the mochi into a flat rectangle slab. The mochi is much less temperamental than piecrust and just needs a firm, even hand. Tadaaki’s mother used to roll the mochi out on the hall floor that opens up to the garden but in recent years Tadaaki drags out Christopher’s ping-pong table for the operation. Once the mochi is rolled out and well powdered with potato starch, Tadaaki flips the several centimeter thick rectangle slabs onto a wooden board to dry for a couple days before cutting.

During the holidays we have a lot of food. A lot. I deal with the Christmas food, but Tadaaki’s in charge of the Japanese New Year stuff. And every year the mochi squares start to mold before they get stuck in the freezer. Last year, Tadaaki had (what he thought was) the brilliant idea of smoothing the hot mochi into heavy-duty plastic pickle bags to deter the mold that tends to form a few days after the mochi is fully dried. I tried to dissuade him, but he would not be budged. Air-drying creates a delicate semi-dried crust, silky smooth from the potato starch and cool to the touch. The gooey plastic-wrapped version just couldn’t compare. The mochi inside the blue-lettered (unattractive) bags looked unappetizing (and was). And in the end, Tadaaki’s “innovative” method didn’t really solve the problem of storing the mochi.

We ended up with a huge slab of mochi not cut up (so unusable) and impossible to put in the freezer (too unwieldy) and this huge slab of mochi sat in the larder (eventually molding). I tried to reason with my very stubborn husband, but he was puffed up like a little boy about his clever new method. Last year, I let him run with it, despite finally having to throw out the mochi that sat in the larder for a couple months. But at the end of shogatsu this year, I enlisted Christopher’s support. The plastic-encased mochi made me gag and I had had enough. The air-drying process is essential to create a wicked surface against which the pounded rice will push off and puff up when broiled. Without that surface, the broiled mochi dipped in soy sauce, then wrapped in nori is unpleasantly gummy (and Christopher agreed). I think we’re going back to the rolling and air-drying next year. Small victories. Life is all about those small victories.

At lunchtime Tadaaki’s brings out the steaming pot of kenchinjiru. We ladle the soup out into handmade pottery bowls and Tadaaki pops a couple hot globs of mochi into each. The mochi melts to a warm, gooey (but tasty) mass. Definitely an aquired texture.

Tadaaki squeezes off more freshly pounded mochi mounds into the grated purple daikon he is growing this year. Purple. I’ve never seen this variety and am captivated by the vibrant lavender against my antique gray pottery bowl. Colors are one of the things I love best about Japan. Sometimes vibrant, sometimes earthy, but always rich in hue and nuanced in texture. I drizzle organic soy sauce over the daikon before greedily scooping a large spoonful or two onto my plate. But every year, it is the natto mochi I crave. Organic fermented soybeans I have aerated vigorously with chopsticks to promote the characteristic threads of natto “slime,” seasoned with a hot mustard paste and organic soy sauce. The blandly, subtle hot mochi contrasts nicely with the fermented natto, making it slightly addicting (for natto aficionados).

This year some of my oldest friends have come and we fall easily back on familiar topics. I uncork the stopper of Harigaya-san’s homemade lager and pour a glass. Life couldn’t get any better and this is one of my favorites days of the year: no responsibility, the warm winter sun and talking leisurely with friends. Sometimes it’s nice not to be in charge.