What does the notion of applying appropriately in the theory of multiliteracies imply

What does the notion of applying appropriately in the theory of multiliteracies imply

Multiliteracies for Collaborative Learning Environments

September 2005 — Volume 9, Number 2

* On the Internet *

Multiliteracies for Collaborative Learning Environments

By Vance Stevens

Petroleum Institute, Abu Dhabi, UAE

The notion of ‘multiliteracies’

The term ‘multiliteracies’ was coined in (1996) by the New London Group ( who? ) to address “the multiplicity of communications channels and increasing cultural and linguistic diversity in the world today” for students and users of technology through “creating access to the evolving language of work, power, and community, and fostering the critical engagement necessary for them to design their social futures and achieve success through fulfilling employment.” As they define the term more comprehensively:

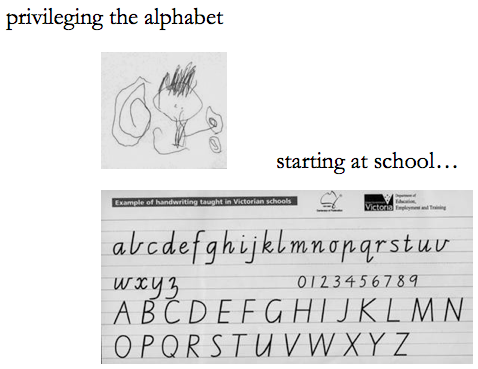

The notion of multiliteracies supplements traditional literacy pedagogy by addressing these two related aspects of textual multiplicity. What we might term “mere literacy” remains centered on language only, and usually on a singular national form of language at that, which is conceived as a stable system based on rules such as mastering sound-letter correspondence. This is based on the assumption that we can discern and describe correct usage. Such a view of language will characteristically translate into a more or less authoritarian kind of pedagogy. A pedagogy of multiliteracies, by contrast, focuses on modes of representation much broader than language alone. These differ according to culture and context, and have specific cognitive, cultural, and social effects. In some cultural contexts – in an Aboriginal community or in a multimedia environment, for instance – the visual mode of representation may be much more powerful and closely related to language than “mere literacy” would ever be able to allow. Multiliteracies also creates a different kind of pedagogy, one in which language and other modes of meaning are dynamic representational resources, constantly being remade by their users as they work to achieve their various cultural purposes.

This notion has struck a chord among educators, as a search on the term in Google will amply reveal. The Canadian Multiliteracy Project for example has mounted a study “exploring pedagogies or teaching practices that prepare children for the literacy challenges of our globalized, networked, culturally diverse world.” Recognizing that “we encounter knowledge in multiple forms in print, in images, in video, in combinations of forms in digital contexts and are asked to represent our knowledge in an equally complex manner,” the site aims at how “educational stakeholders might collaboratively construct and disseminate knowledge” – http://www.pkp.ubc.ca/multiliteracies/

This is but one of many projects addressing the considerable impact of technology on how we formulate meaning and represent it in interaction with others, and how we as teachers must prepare those we influence to cope successfully with the challenges facing them in adapting to these developments. Multiliteracy is more than just ‘multimedia literacy’ or “nontext writing,” which was the topic of a talk given by Elizabeth Daley recently at the University of Michigan, School of Information: http://intel.si.umich.edu/news/news-detail.cfm?NewsItemID=136, but encompasses “approaches to learning that place production technology in the hands of the learner … and recognizes the importance of interactivity and nonlinear skills,” so that various forms of technology become an instrumental part of the learning process.

Nowadays, students and particularly their life-long-learner teachers, are not only having to deal constantly with new technologies impacting their lives, but are having to harness these very technologies to help them keep up with developments in order to in turn use these same technologies to build constructive learning environments. Modeling and implementing the heuristics of effective information management are becoming increasingly crucial responsibilities of educators, which means that educators must themselves become familiar with appropriate applications of a wide range of new technologies. A multiliterate teacher not only understands the many ways that technology interacts and intertwines with academic and personal life, but actively learns how to gain control over those aspects of technology impacting interpersonal and professional development. Furthermore, multiliterate individuals are aware of the pitfalls inherent in technology even as they promote empowerment through effective strategies for first discerning and then taking advantage of those aspects of changing technologies most appropriate to their situations. These strategies include managing, processing, and interpreting a constant influx of information, filtering what is useful, and then enhancing the learning environment with the most appropriate applications, and doing so with awareness of a complex set of socio-political impacts (Selber, 2004; Leu et al, 2004).

Other notions: from ‘print literacy’ to ‘connectivism’

However, Tuman envisaged in his book a ‘docuverse’ where texts interlinked, were neither owned nor fixed, were annotatable (as in a wiki, like Wikipedia http://www.wikipedia.org/), and where print culture was subsumed under a wider range of communications media. Accordingly, there is an emerging body of work distributed over the Internet touching on multiliteracies which incorporate many of these elements. Interestingly, a certain level of multiliteracy is achieved not only in recording and uploading these presentations to the Internet, but also in assuming that there is a multiliterate audience somewhere that has assembled the components on individual computers to enable them to download and play these presentations, and follow the links given that will open a docuverse of resources, some perhaps annotatable. The rapid proliferation of such digital documents suggests a new benchmark regarding the literacy competencies required of a modern multiliterate educator. And the assumption is not necessarily that each educator has the wherewithal to access and understand such presentations, but it does assume that modern educators know how to interact with learning communities that will help them learn from each other and through discovery how to access such presentations, and then make sense of the concepts under discussion.

There have been many studies of how educators form and sustain such communities. One notion is that of communities of practice, two central references for which are Eric Snyder’s ongoing web project at http://www.tcm.com/trdev/cops.htm and Jeroen van de Wiel’s community of practice “hub” at http://communities-of-practice.pagina.nl/. Another revelatory notion is social network analysis, such as that explored in the work of Bronwyn Stuckey http://www.bronwyn.ws/publications/. Noting that the three learning theories with greatest impact on instructional technology (behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism) were all developed before technology had impacted educational environments, George Siemens (2005) has written a compelling article to introduce the notion of “connectivism” and his conclusion is worth quoting:

The pipe is more important than the content within the pipe. Our ability to learn what we need for tomorrow is more important than what we know today. A real challenge for any learning theory is to actuate known knowledge at the point of application. When knowledge, however, is needed, but not known, the ability to plug into sources to meet the requirements becomes a vital skill. As knowledge continues to grow and evolve, access to what is needed is more important than what the learner currently possesses.

Connectivism presents a model of learning that acknowledges the tectonic shifts in society where learning is no longer an internal, individualistic activity. How people work and function is altered when new tools are utilized. The field of education has been slow to recognize both the impact of new learning tools and the environmental changes in what it means to learn. Connectivism provides insight into learning skills and tasks needed for learners to flourish in a digital era.

Examples of and about ‘multiliteracies’

Returning to the topic of what documents both convey and encapsulate concepts inherent in multiliteracies, I have chosen a sampling for an online course I am teaching on the topic. The course is offered by the TESOL, Inc. Certificate Program: Principles and Practices of Online Teaching under the course title PP 107: Multiliteracies for Collaborative Learning Environments. It is described in detail here: http://www.homestead.com/prosites-vstevens/files/efi/papers/tesol/ppot/portal2005.htm

One interesting document, itself a model of multiple literacies in its navigation scheme and content visualization, is a hypertext dissertation by Ahtikari and Eronen (2004) describing a learning space called Netro, in and out of which the document interleaves. Although a good example of ‘docuverse’ there are other presentations touching on multiliteracies which are more ambitious in the ‘multimedia literacies’ involved. Some examples which I use in my course are:

open vs. closed

broadcast vs. conversation

institution vs. individual

hierarchy vs. network

centralized vs. decentralized

product vs. remix

planned vs chaotic

static vs. dynamic

push vs. pull

Internet vs. television

VOIP vs. telephone

blogging vs. newspapers

duplication vs. obliteration

lock-out, lock-in

directed play vs. improv

bundled vs. ‘just there’

layers vs. channels

Although there is no overt mention of multiliteracies in the talk, Downes speaks directly to the language of technology: “the idea that new media is like a new vocabulary, a new language … This new media is how we talk.” He says that the potential of the Internet as a communications tool is realized when we speak not only in the old language but in the new language, “in the syntax of new media.” He says that people need to have a voice in the conversations he refers to, and addresses the power aspects of media control, how free and open access to technology-based media threatens established interests. Control lies at the heart of many of the tensions mentioned above. His parting advice to educators is to ‘let go’ and let chaos be a part of the learning blend. These concepts are discussed in a second part of Selber’s tripartite breakdown of multiliteracies: critical literacy, or an understanding of the socio-political aspects of how technology impacts all our lives, including the time we spend in the educational sector.

One of the first times I heard about blogs was in Jim Duber’s final article (2002) as editor of the TESL-EJ On the Internet column (his last article before he handed off to me). At that time blogging was a little known idea on the verge of revolutionizing student publishing through free and easy access to web presence.

RSS: New killer app for education

The significance of RSS lies in the free-access and open-source side of Downes’s dichotomies. It’s diametrically opposed to a journal subscription in that it’s a way that users of the Internet can generate their own ‘publications’ by steering the information they want to their computers filed neatly in folders with easily accessible headlines and abstracts. It’s a way of filtering all the information that flows over the Internet so that you see just what you think you might be interested in. It is suggested that a derivation of RSS might replace email since its exclusive use would avoid spam. RSS works off Internet sites that provide feeds, i.e. code that feed readers (or aggregators) can read (or interpret, like browsers can interpret HTML and other code) and deliver to your desktop. Many sites that people use to freely publish, such as blogs, YahooGroups, newsgroups, news and weather channels, libraries, and other organizations are increasingly capable of providing feeds that people with feed readers can read.

Many educational thinkers and writers are keeping blogs and updating these almost (and in some cases, as in Stephen Downes’s) daily, and consumers of information who want to cut to the chase and harvest this information quickly will get a free account with a feed reader site such as Bloglines and set up their feeds so that they can glean what they need to know over coffee in the morning. This consumer could be a teacher whose students are keeping blogs, and the teacher might be reading their homework conveniently through a feed reader. Or the teacher (or worker, or any individual or professional) could be checking the musings of his or her workgroup through the same Internet tool that is feeding in the students’ homework and the day’s news, weather, and enlightened ramblings of favored net gurus.

For educators, who are these favored net gurus? Neither coincidentally nor surprisingly, some are the writers and presenters already quoted here, and subscribing to their feed at Bloglines or the feed reader of your choice would keep you current in some small sector of educational technology, on a day by day basis. Here are the frequently updated blogs of some of those cited in this article:

Conclusion

In trying to think of a good conclusion to my article I decided to borrow one. Writing on the need for a “new literacies perspective” Leu et al (2004) conclude that:

Change increasingly defines the nature of literacy and the nature of literacy learning. New technologies generate new literacies that become important to our lives in a global information age. We believe that we are on the cusp of a new era in literacy research, one in which the nature of reading, writing, and communication is being fundamentally transformed.

This belief is increasingly being echoed by educators worldwide. It is incumbent on practitioners in the field to be aware of these echos and gain familiarity with the emerging technologies themselves, in communities with other practitioners, in such a way that they at least keep current, if not ahead of the curve, in applying them to the learning situations in which they practice.

References

Ahtikari, J. & Eronen, S. (2004). On a journey towards web literacy–The electronic learning space Netro. A dissertation submitted at the University of Jyvaskyla Department of Languages. Retrieved September 26, 2005 from http://kielikompassi.jyu.fi/resurssikartta/netro/gradu/index.shtml.

Duber, Jim. (2002). Mad blogs and Englishmen. TESL-EJ 6, 2 (On the Internet). Retrieved September 26, 2005 from http://writing.berkeley.edu/TESL-EJ/ej22/int.html

Leu, D., Kinzer, C. Coiro, J. & Cammack, D. (2004). Toward a theory of new literacies emerging from the Internet and other information and communication technologies. In Ruddell, R. & Unraued, N. (Eds.). Theoretical models and processes of reading (5th edition). International Reading Association

New London Group. (n.d.). About the New London Group and the International Multiliteracies Project in the Education Australia Online. Retrieved September 26, 2005 from http://edoz.com.au/educationaustralia/archive/features/mult3.html

Richardson,W. (n.d.) RSS Quick start guide for educators. Retrieved September 26, 2005 from http://static.hcrhs.k12.nj.us/gems/tech/RSSFAQ4.pdf

Selber, S. (2004). Multiliteracies for a digital age. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning 2, (1). Retrieved September 26, 2005 from http://www.itdl.org/Journal/Jan_05/article01.htm

Snyder, E. (n.d.). CoPs (Communities of practice). tcm.com inc. Training and Development Community Center. Retrieved September 26, 2005 from http://www.tcm.com/trdev/cops.htm/p>

Stevens, V. (2004). The skill of Communication: Technology brought to bear on the art of language learning. TESL-EJ 7, 4 (On the Internet). Retrieved September 26, 2005 from http://writing.berkeley.edu/TESL-EJ/ej28/int.html.

Tuman, M. (1992). Word perfect: Literacy in the computer age. University of Pittsburgh Press.

Unsworth, L. (2001). Teaching Multiliteracies across the curriculum. Buckingham-Philadelphia: Open University Press. Retrieved September 26, 2005 from http://mcgraw-hill.co.uk/openup/chapters/0335206042.pdf courses.

© Copyright rests with authors. Please cite TESL-EJ appropriately.

Editor’s Note: The HTML version contains no page numbers. Please use the PDF version

© 1994–2022 TESL-EJ, ISSN 1072-4303

Copyright of articles rests with the authors.

Multiliteracies

The New London Group (1996) introduced the term “multiliteracies” with a view to accounting not only for the cultural and linguistic diversity of increasingly globalized societies and the plurality of texts that are exchanged in this context, but for the “burgeoning variety of text forms associated with information and multimedia technologies” (p. 60). Distinguishing multiliteracies from what they term “mere literacy” (a focus on letters), the group calls for attendance to broad forms of representation, as well as to the value of these forms of representation in different cultural contexts. Our readings for this week are the New London Group’s original 1996 article in the Harvard Educational Review, as well as selections focusing on multimodality and media literacy by, respectively, Kress and Messaris. You may post your thoughts on these articles as a comment on this post or add a new post of your own.

1 Janet Pletz

Imagine being one of ten people arriving in a small town resort called New London, in rural New Hampshire, in 1994. Each of you arrive, having come from three continents, having worked together, or studied together over the course of your professional lives. You have checked in for a week, and the group is on a mission—to discuss the state of literacy pedagogy. One of the pedagogical concerns guiding the group is ‘the question of life chances as it relates to the broader moral and cultural order of literacy pedagogy—an awareness accentuated by merging global, cultural, social and institutional changes.

“As soon as our sights are set on the objective of creating the learning conditions for full social participation, the issue of differences becomes critically important. How do we ensure that differences of culture, language, and gender are not barriers to educational success? And what are the implications of these differences for literacy pedagogy?”

In my readings this week, these questions are the ones that have fixed in my mind—and as an educator, resonate with an ethical sense of responsibility. These are not easy questions to answer in practice. The reality of working in the day to day quest to meet the literacy and educational needs of all students has swallowed-me-up in my career! As the London Group have demonstrated, these questions can prompt a lifelong commitment. Perhaps as a starting point this week, I wonder how each of you have thought about the implications of these differences of culture, language, and gender—as barriers (or not) to educational success?

To respond to your question, I ended up reflecting on a teaching experience I had about 15 years ago here at UBC.

I was hired to teach English in a program for Aboriginal youth (grades 10 and 11). These students came to live at UBC for 6 weeks, and they stayed in the student residences. The intention of the program was to give these students a sense of the academic pathways that would get them into careers as well as a taste for the kinds of challenges they would face in post-secondary education. I was specifically requested to give them a shortened first year English class (I was a sessional lecturer at the time), and to expose them to the material and assessment approaches they would encounter at UBC.

Well, that is how I started out, but it didn’t go so well.

All of the students were native speakers of English, but few of them expressed any strong feelings of comfort or control when asked to write, particularly when they were asked to produce academic work. For these students, the literacy practices I was offering to teach seemed obscure, arbitrary and somewhat irrelevant to them, and in light of these perceptions, they often described themselves as being unmotivated and lacking any hope of becoming “good” at English. The “diagnostic” essay that I had the students write revealed more about the weakeness with my own curriculum than any weaknesses that might have existed in the students’ writing. The first year tour of English I had planned would reinforce these students’ perception that they couldn’t write and that, in relation to the post-secondary context, they would be on the margins of the dominating culture as embodied in an institution like UBC, unsuited to be members of the academic community.

So what to do? Fortunately, I was able to consult with some First Nations elders who were working with the program. One of the elders, in particular, told me about how uncomfortable he felt living on campus, and how it reminded him about his own experiences with residential schools. It had never occurred to me that someone could look at UBC and have such feelings. It had not occurred to me that the students might not feel at home on campus, or out of place, and that the academic writing I was teaching might, to some, seem like a white-washing the differences of culture and language away from these students.

I ended up throwing out all of the texts that I had planned to use and in their place, brought in a variety of texts all written by First Nations writers on issues that I hoped would be more meaningful to the students. Shakespeare got the boot to be replaced by Thomson Highway. Atwood lost out to Sherman Alexie. I looked for texts that offered ways for students to explore identity, politics and history from positions somewhat closer to their own experiences. I changed the assignments to focus on shorter pieces of writing, in more of a tutorial style, and had the good fortune to be able to bring in an elder to teach the students characteristics of oral storytelling. I still worked on helping students to improve their writing, but I did so with writing that was more connected to their own lives. I tried to make the writing activities less obscure, arbitrary and irrelevant so as to help them build confidence in their ability to express themselves, through writing, authentically and creatively.

I learned a lot from this experience (and went on to teach for 3 years in similar, year-long programs). In particular, I came to better understand just how much literacy practice is caught up in sociocultural issues, issues that can turn educational opportunities for some into significant barriers for others.

I really enjoyed reading your example. It is far from easy for instructors/professors/teachers to see and understand where their students come from, what their lifeworld experiences are, and to use these experiences in their teaching. You were lucky to be able to consult with some First Nations elders, and to invite one in your classroom. What a great opportunity for the students! These students were also lucky to have you! Gee (in his essay New People in New World, 2006) explains that the set of pedagogical principles suggested by the multiliteracies project should be seen as a “Bill if Rights” for all for all children (I think the term ‘learners’ would have been a better choice of word), but “especially for minority and poor children.” Gee states that they have the right to “lots of Situated Practice”, to Overt Instruction, to Critical Framing and to Transformed Practice. It seems to me you clearly acknowledged your students’ rights and did something about it!

It is also very interesting to me that your example does not refer in anyway to the use of digital literacy. Some articles I have read (or skimmed through) over the last few weeks equate ‘multiliteracies’ with ‘digital literacies’. If students are typing a text on a computer, they are engaging in multiliteracies practices, right? The pedagogy of multiliteracies defined by the New London Group encompasses much more than the mere use of computers! At my school, all students from grade 4 to grade 6 may now work during class time on a laptop, paid by the school board. In my opinion, it clearly does not mean they engage with digital literacy in critical ways. It does not mean they know how to transform what they have learn, break it, and innovate for their own social, cultural, and political purposes (Gee, New People in New World, 2006). The introduction of a new tool does not automatically modify people’s actions.

Thank you for this rich discussion everyone!

Janet, your comments on the ethical sense of responsibility etc.. was what I have been thinking about since I read for class. All of those questions brought up by the London Group do promote a lifelong commitment. Cummins (2002) made an amazing comment that has stuck with me since I read it. He said, “our commitment is not only to the individual student who sits in front of us but also to the social fabric into which our individual realities are woven” (p. 539). I think as a language/literacy educator I need to reflect on this and recognize that this is my job.

As an ESL/technology teacher, I had a lot of instances when I struggled with meeting the needs of all my students. My school was made up over 87% ESL. We had over 37 languages. All of my students (at least in my class) were ESL. Some of them had been refugees. Others had only been in Canada for a short period of time. Often, I wondered how I could get through a day. Literacy was particular difficult in my classroom. In addition to the obvious ESL struggles with reading etc., I had to consider my book choices carefully; taking into considerations cultural factors etc.. But as The New London Group (1996), “when the proximity of cultural and linguistic diversity is one of the key facts of our time, the very nature of language learning has changed.”

I like the statement that the New London Group makes regarding how an educator’s job is not to “produce docile, compliant workers. Students need to develop the capacity to speak up, to negotiate and to be able to engage critically with the conditions of their working lives.” As educators we are suppose to be teaching for the future, teaching global citizens. I think we are doing a disservice to our profession and students when we are not considering these issues in our classroom.

Jeff, thank you for sharing your experiences! I really enjoyed reading it. Like Genevieve I agree that your students were lucky to have you!

Genevieve, I was thinking about your last comments regarding Digital Literacy and multiliteracies. I agree of course. Just because you are using a computer in the classroom does not mean that you are engaged in digital literacy in a critical way. Leu (2002) discusses how educators have to assist students become more critical consumers of the new literacies. Hopefully educators are considering this as part of their teaching practices.

The basic issue is that the Christian librarian feels her human rights are being infringed upon by the presence of the gay- straight alliance club.

The librarian made harassment charges against the club sponsor. Investigations by both Vancouver school board and the B.C. human rights tribunal occured. Her claims against the gay straight alliance teacher and school principal have been dismissed as being without merit.

So, as much as we think we are heading into a brave new world of diversity and inclusion, we sometimes are pulled backwards. As F. Scott Fitzgerald put it, “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

As a teacher in the school, I have a slight feeling of what it must have felt like in the McCarthy era. The attempt by a teacher to make the school more inclusive turned into a two year nightmare for her.

Even though both investigations came down in the gay/straight alliance teacher’s favour, the issue won’t go away as you can see by the courier article.

Once again, our many voices bring forward so many perspectives. Jeff and Peter, your experiences in the secondary/tertiary classroom remind us of the complex, “complicated conversations” (Pinar, 2005) of a teaching life. I wasn’t aware of the background to the issues playing out in your school Peter. Thanks for providing the link. And Jeff, amongst all the inherent difficulty, the outcome of your experiences was completely inspiring! We can only hope that we can move our students into a globalized society with the multiliterate skills to live well in the world. Genevieve, I see Gee’s comment as a “Bill of Rights” as something that will change our roles as teachers and teacher-educators now. There is such urgency, frightening so in some ways. And yes, Melanie, knowing your school in Calgary so very well, your day to day lived experience in the classroom is one that every one of the 6000 teachers in our school board should experience, a day in the life of…. becoming Canadian, and literate in a multilterate society.

Anstey and Bull (2006) describe a multiliterate person as someone who “can interpret, use, and produce electronic, live, and paper texts that employ linguistic, visual, auditory, gestural, and spatial semiotic systems for social, cultural, political, civic, and economic purposes in socially and culturally diverse contexts” (p. 41). I believe ‘becoming’ multiliterate is a lifelong venture, and while we can open doors and create deliberate, knowledgeable learning environments for exploration in schools, there is so much more beyond. I think of myself in this precise moment…if I had mark-up skills, I could have re-produced this quote into a very clear, explicit model as it appears on the page!

I do feel compelled to share my fears too. In my ‘teacherly’ and personal life, I dwell in my world with language, lived and felt for its aesthetic beauty, where the experience of meaning making through language is a pleasurable pursuit. It is my enduring piece of philosophy in my practice that my young, young students leave my classroom in June each year with this seed within them. I fear that the necessities and stresses of our complex, global lives, and the changing roles and needs of literacy, will leave the aesthetics and beauty of language ‘busted up’ for the privileged–in specificity–along distant boundaries.

I follow you, Peter..

Janet, I love that term, “multiliterate.” It really sums up our jobs as educators, or at least my job as an educator.

Peter, thank you for sharing that article. I sort of reminded me of a case in my school were Muslim students asked if they could pray in a classroom at lunch time. There was a huge discussion on it during our staff meeting. In the end, it was allowed. Although, slightly different in nature, there was this story this past week in Alberta:

In this article, a transgendered teacher is fired from his job because his gender change does not align with the beliefs of the Catholic Church/School Board. It is mentioned that he was praised for being a good teacher when dismissed.

I agree, about your comments regarding pulling backwards and inclusion. It is becoming quite apparent from all of these news stories, this is happening.

Hi Melanie et al,

I know this is starting to veer away from literacy a bit, but it does have to do with ” socially and culturally diverse contexts” ( thanks for the definition Janet.)

I imagine the Catholic church has the right to say who should or shouldn’t teach at their school. They are a private organization. (I know they get more tax money than in B.C., but I think they still get to retain the ‘private’ designation- go figure)

But I do have trouble when we start opening up our public schools to religious groups.

I wish I had been asked if a Christian club should be allowed in our school as you were with the Muslim group. I would have said no for the kinds of problems we are going through at our school.

I have nothing against these religions, but the problem with their active presence in schools is that we are talking about someone’s god. That tends to be difficult to argue with, because their god is almost always right.

My hope is that we can start to open up our curriculum to other races, genders and classes, but we are always distracted by this age-old question. How can I teach a short story by a gay author like David Sedaris, if i am constantly looking over my shoulder worrying about someone’s religious interpretation of my teaching?

Wasn’t our nation and our public school system based on the notion of separation of church and state?

It might seem messy to have to address these issues in this way, but beneath the fine sounding words of the New London group, the struggle to make our classrooms more open to under-represented sectors of society requires this kind of analysis.

The focus of this course has led me to be considering the process and the technicalities of the communication, both in the reading packages and the blogs as much the actual content. I find myself searching for the correct word for this bird’s eye view perspective perhaps it is hypermediacy? I am fascinated by the flow of the blog from one idea to the next (from multiliteracies in education to human rights). As a drama teacher I appreciate the successful Offering and Accepting which is inherent to any good improvisation, and apparently any blog worth its bits and bites.

Through my participation in this blog, I am coming to a fuller understanding of the content of the course, not only through the compounded knowledge shared, but by observation of the process itself. What an amazing tool this asynchronistic multi-player conversational medium truly is. How revolutionary, that we can hold a conversation over a week’s time at our own leisure, and that I can go back and re-read the ideas stated here, and without a jarring sense of derailment, address an earlier posting thread that interests me, with no limitations on chronological sequence. So four weeks into the course and I feel like I’m starting to “get it.” (I keep searching for a word to better express the way I’ve been experiencing the content of this course, but I can’t seem to find it, any suggestions?)

From a pedagogical standpoint, I find it interesting, that it was not the articles themselves that brought me to this understanding, but through participating in the actual activity. In other words, I did not come to this knowledge through traditional “verbal” literacy, but through some other kind of literacy, perhaps interpersonal literacy.

I totally film-geeked-out when I read Messaris’ Visual Aspects of Media Literacy. I’ve studied cinema craft with a focus on cinematography, and since then it is almost impossible for me to watch a film, without being acutely aware of the visual messages being sent. In fact, as much as I love movies, I enjoy most of them a little less now, because my insider knowledge of the visual messages has rendered many of them far too predictable. Perhaps this is why I’ve come to enjoy independent and foreign films so much, because they stray from the visual formulae that I know too well, allowing me to enjoy the experience of watching a transparent film and lose myself in the story. Or at least be intrigued by the use of different visual techniques. So I’ll likely check out some flicks at the VIFF http://www.viff.org/

Peter, thank you for raising those points. They are all very valid. I agree with your comment on the Catholic School Board having the right to decide who they want to teach in their school board. However, I think the issue with this particular case was more that the teacher was already working for the board and a competent teacher. Once the school board found out about his transgender status, they decided to fire him. I think this conversation goes a bit beyond the scope of our course and our discussion.

As for your comments about Christian clubs etcs, I understand. I think part of the issue that bothered me with this particular situation was that teachers were asked to supervise the Muslim prayer sessions. What if a Christian (or another religionous group) teacher is not comfortable with supervising a Muslim prayer time? Should we not be respecting teacher’s beliefs as well? It does create a lot of issues. My school board had decided to take on a secular approach to learning and I think that it should remain as such. As teachers, we should respect all religions and leave it at that.

I enjoyed the conversations so far around the diversity of learners in schools and our necessary accommodations. Jeff, Peter, Janet, and Melanie did a great job outlining there experiences.

I was wondering if I could take the conversation in a slightly new direction. I noticed the second component of multiliteracies as outlined by the New London Group – that regarding the increasingly multimodal aspects of literacy. The two-fold definition is below:

“First, we want to extend the idea and scope of literacy pedagogy to account for the context of our culturally and linguistically diverse and increasingly globalized societies, for the multifarious cultures that interrelate and the plurality of texts that circulate. Second, we argue that literacy pedagogy now must account for the burgeoning variety of text forms associated with information and multimedia technologies” (New London Group, 1996).

The New London Group did the ground work and the call to arms, and people like Messaris, Kress, Kalantzis, and Cope further specified and enhanced the work.

I agree with Kress in his statements that English (as a subject in schools) must adopt a curriculum which addresses texts that are not just words on paper from the traditional canon of literature (Kress, 144). Though, I believe that the occasional substitution of the canonical texts (with which Jeff found so much success) and the changing of what we consider “text” to be are both necessary to our students’ success.

I loved how Messaris linked these ideas to media literacy. His examples were very relatable. I completely believe that a more multi-modal approach to analysis of media texts is necessary. The syntax of the visual mediums is very fascinating.

I would also say that a multimodal perspective is valuable in text production. If we ask students to analyze multimodal texts then why not have them produce their own too? I’ve begun experimenting with this in my own teaching in recent years.

As a final note, Messaris’ account of “graphic displays of quantitative information” instantly reminded me Teresa’s mandala software for Romeo and Juliet (Messaris, 72). I think the technology is finally allowing for exciting reinterpretations of text which increasingly leans towards the visual aspect.

Genevieve, I wanted to briefly respond to your discussion of what multiliteracies are, and when/if they are inclusive of criticality. I think you raise a great point that writing on a computer is not necessarily critical engagement with digital literacy. Part of me agrees with you, but the other part of me thinks that the medium is important, and that there is indeed something different about writing on a computer than on a piece of paper- that shifts the kind of literacy it requires. If nothing else, the embodied experience and relationship to what is being written changes—the feel of the paper, the backspace that leaves no marks as opposed to holes in binder paper where you erased too hard, the sound of typing on keyboard. While I think critical multiliteracies definitely means being able to encode and decode messages and texts, and engage in creation of those texts, I’m not sure about the link between criticality and multiliteracy. Being literate in the older definition- as in being able to read, doesn’t mean one is critical- lots of people read newspapers, magazines, etc without being able to critically engage with those media messages. In the same way, I wonder if you can be multiliterate and be unable to engage critically with media messages- surely, we all know people who can write beautifully, edit video and upload to a server, sequence photos to tell a story, and tell stories to others without being critical of the information. In thinking about what it means to have critical multiliteracy, I found especially useful the Elements of Linguistic Design that the London Group detailed. However, I am wavering back and fourth as to whether being able to engage in a diversity of media spaces, and having multiliteracies, always means one is able to be critical of those spaces, or to think critically about the construction of those messages and spaces. I guess I think that while its ideal for people to be able to engage critically with texts, I’m not sure its critical to multiliteracy that they be able to do so.

I found the discussion on design- from Kress and the New London Group, especially interesting. While our discussion as of yet centers mostly on the mainstream schooling system, I think these ideas are also very relevant to other kinds of learning spaces where learning is unstructured or informal. The discussion around design seems to engage a tension between mainstream schooling and learning in informal spaces. I am particularly interested in learning that occurs within informal spaces, especially digital ones, so my perspective comes from that point of view. Within new media/digital spaces, how the space is designed- its architecture- permits for/releases certain kinds of mobilities, and restricts others. Related to what many of you have talked about in your posts, the media- and medium- design of space facilitates who can participate, and how they participate. I was a bit taken aback by Kress’ example of girls and boys use of digital media, where he writes:

“Now communication happens in new communicational webs. The 12 year old boy who spends much of his leisure time either by himself or with friends in front of a playstation, lives in a communicational web structured by a variety of media of communication and of modes of communication. In that, the `screen’ may be becoming dominant, whether that of the TV or of the PC, and may be coming to restructure the `page’……… In contrast, the 12 year old’s 10 year old sister is likely to live in a quite differently structured communicational web; yes TV and PC figure, but quite differently. Instead of the books on science fiction (derived from playstation games) or books on games themselves, there might be much more conventional narratives, and the

magazines might be absent. Talk would figure more prominently, as would play

of a self-initiated kind. (143)

I think Kress makes a good point talking about new communicational webs, and acknowledging the interplay of a variety of mediums in meaning-making. He also alludes to a distributed sense of self, here, which I think is key in thinking of power, knowledge, difference, and multiliteracies- reminded me of Stephen Shaviro’s work on networks. I know his mention of gender is fleeting, but fleeting as it was, it was also discerning. The way he genders this integration with networks seems a bit off.

Sure, the way that people of distinct social locations engage with media is unique, and the way that mediated spaces are structured plays a role in how Others can interact, or can subvert, but the notion that “his ten year old sister,” which I took to mean “pre-adolescent girls” use “conventional narratives” and that magazines are absent, is not very critical. Many scholars have written about active participation and use of both new and old media texts, (Radway, romance novels, McRobbie, Kearny, bedroom culture) by girls, in situations where girls subvert media materials for their own use or interact with them in empowering ways where they take advantage of the design to be active, engaged members who contribute to publics and in some cases create counter publics. Girls are, in fact, engaging in significant ways with digital media- a PEW foundation study found teenage girls are the largest growing group of social networking sites, and are more likely than boys to post visual texts- video, photo, etc- to the Internet. This definitely suggests girls are living in a communicational web where digital literacies and visual modes of communication are dominant. There is also a long history of girls’ engagement with ‘zines, and so I am confused as to what he means about magazines being absent- girls long since have been producers and creators, as well as readers, both of mainstream magazines and “zines.” As for “conventional narratives” and “play of a self-initiated kind” I am not totally clear on what he means, though I take it to mean that girls interact less with networked meaning, don’t create their own narratives (but use conventional ones put fourth about gendered beings/male gaze by the mass media) and engage in play that is self-initiated—does this mean they engage in play that does not involve media? Then, based on what I’ve already written, this is surely not the case. Kress makes some great points, but by using this example and failing to enter into the criticality of gender and digital media seriously weakens his argument.

Design of learning spaces, from their physical architecture, whether it be how the tables are shaped or which language the keyboards are in, is not neutral. As we discussed last week, this has to do with code that allows us to even be media literate. It strikes me this is the similar to the architecture of learning spaces—in order to construct them we must be literate in the world of a carpenter, architect, and builder. Interestingly enough, this rings a bell with Audre Lourde’s argument that the Master’s House will never be rebuilt with the master’s tools. Lourde is talking about language, primarily, that without reconstructing language we are unable to subvert hierarchal power relations that privilege certain groups.

I meant to write about some other things, but really got caught up on gender here- hopefully you don’t mind too much!

Hi everyone,

I hope to contribute to Richard’s thread either here or in class, but I just wanted to respond to Erin’s comments about this blog.

I’ve been reading about the philosophy of hermeneutics and forming my own theories as to potential uses of online discourse in education. Erin, your post is now influencing these theories of mine…

“Through my participation in this blog, I am coming to a fuller understanding of the content of the course, not only through the compounded knowledge shared, but by observation of the process itself. What an amazing tool this asynchronistic multi-player conversational medium truly is. How revolutionary, that we can hold a conversation over a week’s time at our own leisure, and that I can go back and re-read the ideas stated here, and without a jarring sense of derailment, address an earlier posting thread that interests me, with no limitations on chronological sequence.”

I love this! As you mentioned, it is an experience that is hard to explain…I also feel it has to do with the time for reflection..reading a comment but then having time to mull it over before posting a response. When I first started teaching online in 2005, I was absolutely amazed with the dialogue amongst students in the forums (blogs). The critical level of the discussions went beyond what would occur in the traditional classroom. Students not only developed good writing skills but appreciated the intimacy of the course, between students and instructor, even though we never met face to face. In some cases, we felt more ‘connected’ most likely because of the online contact that occurred outside of the three hour time frame. I see these online forums as a place for recording and archiving creative process that can be accessed for reflection and analysis. It is a place for dialogical interpretation….and I really liked your phrase “interpersonal literacy” 🙂

For those who are unfamiliar with what hermeneutics means (was not that long ago that I couldn’t describe it), a very basic definition is the theory of understanding and interpretation of linguistic and non-linguistic expressions. As I tackle readings on hermeneutics for another course, I am wondering if the blog, when used in the manner we are using it in this class, can be thought of as a hermeneutic circle. In ‘Beyond Objectivism and Relativism: Science, Hermeneutics, and Praxis’ (1983) Bernstein describes the hermeneutic circle as “a type of understanding that constantly moves back and forth between “parts’ and the “whole” that we seek to understand.” He quotes Geertz when further describing it as “a continuous dialectical tackling between the most local of local detail and the most global of global structure in such a way as to bring both into view simultaneously.” This is what I was reminded of when I read Erin’s comments (thanks Erin!) 🙂

I will leave you with a quote from David Smith’s “The Hermeneutic Imagination and the Pedagogic Text” (1999) – one of my favourite hermeneutic texts so far. I know this particular post of mine doesn’t directly relate to this week’s readings, but then again maybe it does…As Genevieve pointed out above, literacy involves more than just reading and writing – we have to learn more about how our students understand the technologies they use and how they use the technologies to understand.

“In the terms elaborated by Gadamer and Richard Rorty, the hermeneutic modus has more the character of conversation than, say, of analysis and the trumpeting of truth claims. When one is engaged in a good conversation, there is a certain quality of self-forgetfulness as one gives oneself over to the conversation itself, so that the truth that is realized in the conversation is never the possession of any one of the speakers or camps, but rather is something that all concerned realize they share in together.”

Also, can I suggest that another way of making canonical texts powerful for kids who don’t relate is through art- check out Tim Rollins and Kids of Survival, in NYC. I recall an art piece they made collectively where they read a required high school text, tore up the pages, pasted them onto gigantic canvasses, and painted wounds on top of the pages– very powerful, and fascinating way of thinking about addressing access, and shfiting relations of power through multiliteracy.

Chelsey, I agree with what you wrote about Kress’ gender example. I responded favourably to the overall argument Kress makes in his article as he highlights some extremely important issues, but I did find some of his examples to be problematic. For instance, the Islington Summer University letter/invite seemed more like a stepping stone to and inspiration for his discussion of the “dissolution of institutional frames” argument rather than a defining document that “encapsulates most of the criterial features of the current environment for education”.

I also want to point out that the curriculum debate Kress writes about in 2000 (transitioning from educating for an industrial society to educating for instability) is not new. Perhaps the discussion of “changing landscapes of representation and communication” (p. 138) is more central to current debates, however, there has been ongoing debate regarding the purpose for educating children since the early 20th century (see Pagano, J. (1999) The Curriculum Field: The Emergence of a Discipline. In W. F. Pinar (Ed.), “Contemporary Curriculum Discourses” (pp. 82-105) for a condense overview that focuses primarily on debates within the United States spanning the 20th century). Most of the debates I am familiar with often originated from the pivotal curriculum texts of Ralph Tyler (1911) and Franklin Bobbitt (1918), including of course leaders such as John Dewey and more recently Eliot Eisner. Perhaps the UK history of curriculum theory is quite different. When I was studying these texts last year, I came across a reference to what I believe to be an extremely significant question for us to think about during this week’s conversations. The question was raised by Herbert Spencer in 1860. Herbert Kliebard (1975) writes of how Spencer anticipated the trend toward specificity in stating educational objectives, yet that Spencer also identified the scope of the school curriculum with life itself: “Spencer, it should be remembered, asked the question “What knowledge is of most worth?,” not merely, “What shall the schools teach?” While reading Kress, I could not help but wonder why he wasn’t acknowledging curriculum debates of the past and the potential to learn from them as we proceed towards “designing” curriculum for the future, not to mention previous discussions of perceptions surrounding knowledge (article word length restriction? context of particular journal?)

Kress writes,”What are the features of an education for instability? This of course touches decisively on the question of identity and its relations to pedagogy and knowledge.” I want to know more about this…

Michael Apple in “Ideology and Curriculum” (2004) would have us look beyond what Kress is saying to identify how we got to where we are, to examine the relationship between the institution of education and the economies of services and information that Kress writes about. Yes, design and agency will be central to future curriculum but let us not forget the knowledge we are producing. Kress touches on values and ethics within this shift from state to market, but perhaps not as much as he could have.

Apple writes, “…knowledge that now gets into schools is already a choice from a much larger universe of possible social knowledge and principles. It is a form of cultural capital that comes from somewhere, that often reflects the perspectives and beliefs of powerful segments of our social collectivity. In its very production and dissemination as a public and economic commodity – as books, films, materials, and so forth – it is repeatedly filtered through ideological and economic commitments. Social and economic values, hence, are already embedded in the design of the institutions we work in, in the “formal corpus of school knowledge” we preserve in our curricula, in our modes of teaching, and in our principles, standards, and forms of evaluation. Since these values now work ‘through’ us, often unconsciously, the issue is not how to stand above the choice. Rather, it is in what values I must ultimately choose.” (Ideology and Curriculum, 3rd Edition, p. 8)

I’m not sure where I’m going with this by bringing Apple’s neo-marxist perspective into the discussion. I just get this feeling that there is more to think about besides what Kress has given us. And, please don’t misunderstand me, I do like what Kress has to say…I’m just inspired to think beyond the text.

Emma,

I enjoyed reading your ideas about advertising. This touches on something that has sparked my interest in reading these posts- the ability to be very multiliterate, to engage powerfully and persuasively with visual texts, but to not be “critical” of them, of how they are constructed.

Thanks Heidi for your insight! You’ve helped me understand some of my own ideas a bit better 🙂 As far as the phrase interpersonal literacies, I’ve using the sense of the term interpersonal from Howard Gardner’s theory of Multiple Intelligences.

Just trying to wrap my head around this concept of hermeneutics that you’ve brought up.

Don’t mean to add more for you to wrap your head around Erin…that’s just where my head is! I have a habit of making things more complicated for myself. Hermeneutics will always be there for you to think about when you are ready to…it’s not going anywhere…

Genevieve, hmmm I’m skeptical about this Vook thing. And not out a nostaliga for traditional print format. I would be very interested to see studeies on brain activity reading a book versus “reading” a Vook. I love the quiet of a book, the lack of bright and noisy stimuli, I wonder if reading a Vook would be more stressful than reading a book, I totally see it’s value for textbooks, especially ones to show processes: cooking, biology etc. But I don’t know if I’d want to curl up in bed with it to read a story.

wow, you can tell I wrote that last posting with the distractions of being at work, please excuse all the typos.

here’s a thought on the stability of technological change:

Kress abstractly relies on the notion that we are living in unstable times. Explicitly he writes, “Stability has been or will be replaced by instability.” He defines this age of instability as opposed to the Ford-era in which policies attempted to enact a top-down approach to institutional control. But, I am wondering is a negative definition of instability (i.e. instability of our time is defined as opposed to the Ford-era) enough of a definition. Maybe we could turn our notion of the changing times, into a model of stability. If technological change is a marker of this era, then we, the participants of this era, come to expect change with a stabilizing function. So, if technological change is something we come to expect and rely on then can’t development become a form of cultural stability? If we recontextualize stability in this way, what are some changes we could see in Kress’ argument?

It’s great to hear from experienced educators who navigate such a complex environment of cultures, languages, and individualities. Given that my teaching experience comes from only two years of TAing first year english here at UBC, my students and I can communicate pretty seamlessly in English, and the power dynamics are not as fraught because I am so close in age to my students, or maybe it’s worse, I don’t know. In any case, it’s tough and I applaud all of your commitment to work through these issues.

Multiliteracies (New London Group)

Summary: Multiliteracies is a pedagogical approach developed in 1994 by the New London Group that aims to make classroom teaching more inclusive of cultural, linguistic, communicative, and technological diversity. They advocate this so that students will be better prepared for a successful life in a globalized world.

Originators & Proponents: New London Group

Keywords: communication, community engagement, cultural diversity, education, expression, globalization, language, linguistic diversity, literacy, modes, multimodality, pedagogy, technology

Multiliteracies (New London Group)

According to the NLG, a multiliteracies pedagogy accepts and encourages a wide range of linguistic, cultural, communicative, and technological perspectives and tools being used to help students better prepare for a rapidly changing, globalized world. In order to continue helping students have the widest range of opportunities possible in creating their lives and contributing to their community and to their future, school must now adapt to the growing availability of new technologies for teaching and learning, communication channels, and increased access to cultural and linguistic diversity.

The New London Group members are (in alphabetical order): Courtney Cazden (USA), Bill Cope (Australia), Norman Fairclough (UK), James Gee (United States), Mary Kalantzis (Australia), Gunther Kress (UK), Allan Luke (Australia), Carmen Luke (Australia), Sarah Michaels (US), Martin Nakata (Australia).

Multiliteracy

Multiliteracies is a term coined in the mid-1990s by the New London Group [1] and is an approach to literacy theory and pedagogy. This approach highlights two key aspects of literacy: linguistic diversity, and multimodal forms of linguistic expression and representation. The term was coined in response to two significant changes in globalized environments: the proliferation of diverse modes of communication through new communications technologies such as the internet, multimedia, and digital media, and the existence of growing linguistic and cultural diversity due to increased transnational migration. [2] Multiliteracies as a scholarly approach focuses on the new «literacy» that is developing in response to changes in the way people communicate due to new technologies and new shifts in the usage of language within different cultures.

Contents

Overview

There are two major topics that demonstrate the way multiliteracies can be used. The first is due to the world becoming smaller, communication between other cultures/languages is necessary to anyone. The usage of the English language is also being changed. While it seems that English is the common, global language, there are different dialects and subcultures that all speak different Englishes. The way English is spoken in Australia, South Africa, India or any other country is different from how it is spoken in the original English speaking countries in the UK.

The second way to incorporate the term multiliteracies is the way technology and multimedia is changing how we communicate. These days, text and speech are not the only and main ways to communicate. The definition of media is being extended to include text combined with sounds, and images which are being incorporated into movies, billboards, almost any site on the internet, and television. All these ways of communication require the ability to understand a multimedia world.

The formulation of «A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies» by the New London Group expanded the focus of literacy from reading and writing to an understanding of multiple discourses and forms of representation in public and professional domains. The new literacy pedagogy was developed to meet the learning needs of students to allow them to navigate within these altered technological, cultural, and linguistically diverse communities. The concept of multiliteracies has been applied within various contexts and includes oral vernacular genres, visual literacies, information literacy, emotional literacy, and scientific multiliteracies and numeracy. [3]

Application to the real world

Due to changes in the world, especially globalization and an increase in immigration, a debate has arisen about the way students are instructed and learning in school. English, and all subjects, should evolve to incorporate multimodal ways of communication. The New London Group (1996) proposes the teaching of all representations of meaning including, linguistic, visual, audio, spatial, and gestural, which are subsumed under the category of multimodal. A pedagogy of multiliteracies includes a balanced classroom design of Situated Practice, Overt Instruction, Critical Framing and Transformed Practice. Students need to draw on their own experiences and semiotic literacy practices to represent and communicate meaning.

The changes that transpire through the field of education affect learning processes, while the application of learning processes affects the use of multiliteracies (Selber, 2004). These include the functional, critical, and rhetorical skills that are applied in diverse fields and disciplines.

Educational pedagogies, including Purpose Driven Education, integrate the use of multi-literacy by encouraging student learning through exploration of their passions using their senses, technology, vernaculars, as well as alternative forms of communication.

The New London Group

The New London Group is a group of ten academics who met at New London, New Hampshire, in the United States in September 1994, to develop a new literacy pedagogy that would serve concerns facing educators as the existing literacy pedagogy did not meet the learning needs of students. Their focus was on replacing the existing monolingual, monocultural, and standardized literacy pedagogy that prioritized reading and writing, with a pedagogy that used multiple modes of meaning making. They emphasised the use of multiple modes of communication, languages, and multiple Englishes to reflect the impact of new technologies and linguistic and cultural diversity, instead of developing competence in a single national language and standardized form of English. [2] The ten academics brought to the discussion their expertise and personal experience from different national and professional contexts. Courtney Cazden from the United States has worked in the areas of classroom discourse and multilingual teaching and learning; Bill Cope from Australia, on literacy pedagogy and linguistic diversity, and new technologies of representation and communication; Mary Kalantzis from Australia, on experimental social education and citizenship education; Norman Fairclough from the United Kingdom, on critical discourse analysis, social practices and discourse, and the relationship between discursive change and social and cultural change; Gunther Kress from the United Kingdom, on social semiotics, visual literacy, discourse analysis, and multimodal literacy; James Gee from the United States, on psycholinguistics, sociolinguistics, and language and literacy; Allan Luke from Australia on critical literacy and applied linguistics; Carmen Luke from Australia, on feminism and critical pedagogy; Sarah Michaels from the United States, on classroom discourse; and Martin Nataka on indigenous education and higher education curriculum. The article «A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures», published in 1996, [4] documents the New London Group’s «manifesto» of literacy pedagogy that is recommended for use in educational institutions, in the community, and within organizations.

A pedagogy of multiliteracies

The multiliteracies pedagogical approach involves four key aspects: Situated Practice, Critical Framing, Overt Instruction, and Transformed Practice. Situated Practice involves learning that is grounded in students’ own life experiences. Critical Framing supports students in questioning common sense assumptions found within discourses. Overt Instruction is the direct teaching of «metalanguages» in order to help learners understand the components of expressive forms or grammars. Transformed Practice is where learners engage in situated practices based in new understandings of literacy practices. [4]

Situated practice

Situated Practice/experiencing connects with a tradition called ‘authentic pedagogy’. Authentic pedagogy [8] was first formulated as a direct counterpoint to didactic pedagogy in the twentieth century, initially through the work of John Dewey in the United States and Maria Montessori in Italy. It focuses on the learner’s own meanings, the texts that are relevant to them in their everyday lives. When it comes to reading and writing, authentic literacy pedagogy promotes a process of natural language growth that begins when a child learns to speak, with a focus on internalized understanding rather than the formalities of rules. It is learner-centered and aims to provide space for self-expression.

However, the New London Group (1996) points out limitations to Situated Practice. First, while situated learning can lead to mastery in practice, learners immersed in rich and complex practices can vary significantly from each other and Situated Practice does not necessarily lead to conscious control and awareness of what one knows and does. Second, Situated Practice does not necessarily create learners who can critique what they are learning in terms of historical, cultural, political, ideological, or value-centered relations. Third, there is the question of putting knowledge into action. Learners might be incapable of reflexively enacting their knowledge in practice. Therefore, they clarify that Situated Practice must be supplemented by other components and powerful learning arises from weaving between Situated Practice, Overt Instruction, Critical Framing and Transformed Practice in a purposeful way.

Critical framing

Critical Framing in multiliteracies requires an investigation of the socio-cultural contexts and purposes of learning and designs of meaning. Cope and Kalantzis (2001) [9] discuss this in the context of our increasingly diverse and globally interconnected lives where the forces of migration, multiculturalism, and global economic integration intensify the processes of change. The act of meaning-making is also diversifying as digital interfaces level the playing field.

Mills (2009) [3] discusses how multiliteracies can help us go beyond heritage print texts that reproduce and sustain dominant cultural values by creating affordances for thinking about textual practices that construct and produce culture. Another dimension of this critical framing may be extended to the diverse types and purposes of literacy in contemporary society. The traditional curricula operates on various rules of inclusion and exclusion in the hierarchical ordering of textual practices, often dismissing text types such as picture books or popular fiction. Similarly, items like blogs, emails, websites, visual literacies, and oral discourses may often be overlooked as «inferior literacies». In excluding them from mainstream literacy practices, we become prone to disenfranchise groups and may lose out on opportunities to sensitize learners to consider underlying issues of power, privilege, and prejudice, both in terms of identifying these in societal practices, as well as in questioning dominant discourses that normalize these. Mills also states how some scholars such as Unsworth (2006a, 2006b) and Mackey (1998) suggest an increased blurring of ‘popular culture’ and ‘quality literature’ facilitated by classical literature made available in electronic formats and supported by online communities and forums.

In addition to acknowledging increased socio-cultural contextualization and diversification of text-types, multiliteracies pedagogies also enable us to critically frame and reconceptualize traditional notions of writing, calling into question issues of authority, authorship, power, and knowledge. Domingo, Jewitt, & Kress (2014) [10] address these concepts through a study of template designs on websites and blogs that empowers the readers through non-linear readings paths, with the modular layout allowing them to choose their own reading paths. They also discuss the varying affordances of different modes and how writing become just one part of the multimodal ensemble.

Multiliteracies transcend conventional print literacies and the centrality of cultures that have historically extolled it, offering much scope for arts-based approaches in decolonizing initiatives (Flicker et al., 2014) [11] or reflexive visual methodologies in situated contexts (Mitchell, DeLange, Moletsane, Stuart, & Buthelezi, 2005). [12] However, in so far as access to digital tools and infrastructures is concerned, we still need to take into account issues of agency, capital, socioeconomic status, and digital epistemologies (Prinsloo & Rowsell, 2012). [13]

Overt instruction

Original view

In the original formulation of the New London Group, Overt Instruction was one of the major dimensions of literacy pedagogy that was identified. The original view of overt instruction includes the teachers and other experts’ supporting students through scaffolding and focusing the students on the important features of their experiences and activities within the community of learners (Cope & Kalantzis, 2000, p. 33). Cope and Kalantiz argue teachers and other experts allow the learner to gain explicit information at times by building on and using what the learner already knows and has achieved. Overt Instruction is not, as it is often misrepresented, direct transmission, drills, and rote learning. It includes the kinds of collaborative efforts between teacher and student in which the student can do a task that is much more complex than the task they can do individually. According to Cope and Kalantzis, «Overt Instruction introduces an often overlooked element-the connection of the element of the importance of contextualization of learning experiences to conscious understanding of elements of language meaning and design» (p. 116) Use of metalanguages, Cope and Kalantzis argue, is one of the key features of Overt Instruction. Metalanguages refer to «languages of reflective generalization that describe the form, content, and function of the discourses of practice» (p. 34).

Updated view

Activity type: define terms, make a glossary, label a diagram, sort or categorize like or unlike things Conceptualizing with theory-schematization is a Knowledge Process by means of which learners make generalizations and put the key terms together into interpretative framework. They build mental models, abstract frameworks and transferable disciplinary schemas (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009, p. 185 [6] ). Activity type: draw a diagram, make a concept map, or write a summary, theory or formula which puts the concepts together

Transformed practice

Transformed Practice, originally framed by the New London Group (1996) [5] as part of the four components of Multiliteracies pedagogy, is embedded in authentic learning, where activities are re-created according to the lifeworld of learners. Transformed Practice is transfer in meaning-making practice, which involves applied learning, real-world meanings, communication in practice, and applying understanding gained from Situated Practice, Overt Instruction, and Critical Framing to a new context. Once learners are aware of how context affects their learning, the «theory becomes reflective practice» (The New London Group, 1996, p. 87). In other words, learners can reflect on what they have learned while they engage in reflective practice based on their personal goals and values in new contexts. For instance, learners design a personalized research project on a specific topic.

Transformed Practice subsequently underwent reformation and was renamed «Applying» as part of «Knowledge Processes» (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009, p. 184), [6] formerly known as Multiliteracy pedagogy. Applying is considered as the typical focus of the tradition of applied or competency-based learning (Cope & Kalantzis, 2015). [14] While learners actively learn by applying experiential, conceptual or critical knowledge in the real world, learners act on the basis of knowing something of the world, and learning something new from the experience of acting. That is, applying occurs more or less unconsciously or incidentally everyday in the lifeworld, since learners are usually doing things and learning by doing them. Applying can occur in two ways:

See also

Footnotes

Related Research Articles

Instructional scaffolding is the support given to a student by an instructor throughout the learning process. This support is specifically tailored to each student; this instructional approach allows students to experience student-centered learning, which tends to facilitate more efficient learning than teacher-centered learning. This learning process promotes a deeper level of learning than many other common teaching strategies.

The Association of College & Research Libraries defines information literacy as a «set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning».

Transformative learning, as a theory, says that the process of «perspective transformation» has three dimensions: psychological, convictional, and behavioral.

Transformative learning is the expansion of consciousness through the transformation of basic worldview and specific capacities of the self; transformative learning is facilitated through consciously directed processes such as appreciatively accessing and receiving the symbolic contents of the unconscious and critically analyzing underlying premises.

Situated cognition is a theory that posits that knowing is inseparable from doing by arguing that all knowledge is situated in activity bound to social, cultural and physical contexts.

Computers and writing is a sub-field of college English studies about how computers and digital technologies affect literacy and the writing process. The range of inquiry in this field is broad including discussions on ethics when using computers in writing programs, how discourse can be produced through technologies, software development, and computer-aided literacy instruction. Some topics include hypertext theory, visual rhetoric, multimedia authoring, distance learning, digital rhetoric, usability studies, the patterns of online communities, how various media change reading and writing practices, textual conventions, and genres. Other topics examine social or critical issues in computer technology and literacy, such as the issues of the «digital divide», equitable access to computer-writing resources, and critical technological literacies.

Critical literacy is the ability to find embedded discrimination in media. This is done by analyzing the messages promoting prejudiced power relationships found naturally in media and written material that go unnoticed otherwise by reading beyond the author’s words and examining the manner in which the author has conveyed his or her ideas about society’s norms to determine whether these ideas contain racial or gender inequality.

Composition studies is the professional field of writing, research, and instruction, focusing especially on writing at the college level in the United States. The flagship national organization for this field is the Conference on College Composition and Communication.

Computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) is a pedagogical approach wherein learning takes place via social interaction using a computer or through the Internet. This kind of learning is characterized by the sharing and construction of knowledge among participants using technology as their primary means of communication or as a common resource. CSCL can be implemented in online and classroom learning environments and can take place synchronously or asynchronously.

Allan Luke is an educator, researcher, and theorist studying literacy, multiliteracies, applied linguistics, and educational sociology and policy. Luke has written or edited 17 books and more than 250 articles and book chapters. Luke, with Peter Freebody, originated the Four Resources Model of literacy in the 1990s. Part of the New London Group, he was coauthor of the «Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures» published in the Harvard Educational Review (1996). He is Emeritus Professor at Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, Australia and Adjunct Professor at Werklund School of Education, University of Calgary, Canada.