What events preceded the bill of rights

What events preceded the bill of rights

Unit 6. The Petition of Right and the Bill of Rights

2. Stuart succession

3. Financial control

4. Royal requests

8. Raising taxes.

The Petition of Rights

The constitutional opposition in the XVII century was expressed in emergence in 1628 of the document known as the Petition of Rights. Needing money, the king Charles I tried to receive money from the citizens, passing parliament. In 1628 the parliament forced the king to accept the Petition of Rights, which allowed to raise taxes only with the consent of parliament. This document guaranteed to English citizens basic rights, which any government couldn’t violate.

Text “The Bill of Rights”

Task 3. Read the text and write down Russian equivalents for the words and expressions in bold type.

· constitutional paper – конституционная бумага

· prevented the sovereign from abusing his authority – повелитель препятствовал подрыванию его авторитета

1. Competent authority – авторитетный специалист

9. To hand over one’s authority to smb. – передавать свои полномочия

6. Ограничивать власть монарха – to restrict authority of the monarch

1. The Bill of Rights preceded the Revolution of 1688.

2. King James II had to leave the country to declare illegal various practices.

3. The Bill of Rights regulated succession to the throne since 1688.

4. The Revolution settlement made monarchy clearly conditional on the will of Parliament and provided a freedom from arbitrary government.

5. This document protected the right for a jury, prohibition of cruel punishments, the right of the appeal with petitions to the authorities.

6. A number of clauses eliminated royal interference in parliamentary mattes, stressing that lections must be free and that members of parliament must have complete freedom of speech.

What events preceded the bill of rights

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

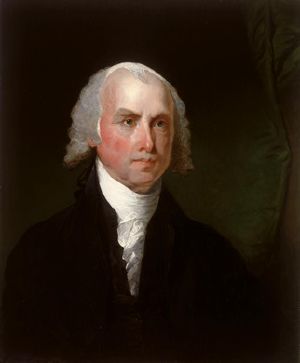

The state conventions that ratified the Constitution obtained promises that the new Congress would consider adding a Bill of Rights. James Madison—the key figure in the Constitutional Convention and an exponent of the Constitution’s logic in the Federalist papers—was elected to the first House of Representatives. Keeping a campaign promise, he surveyed suggestions from state-ratifying conventions and zeroed in on those most often recommended. He wrote the amendments not just as goals to pursue but as commands telling the national government what it must do or what it cannot do. Congress passed twelve amendments, but the Bill of Rights shrank to ten when the first two (concerning congressional apportionment and pay) were not ratified by the necessary nine states.

The Bill of Rights

The first eight amendments that were adopted address particular rights. The Ninth Amendment addressed the concern that listing some rights might undercut unspoken natural rights that preceded government. It states that the Bill of Rights does not “deny or disparage others retained by the people.” This allows for unnamed rights, such as the right to travel between states, to be recognized. We discussed the Tenth Amendment in Chapter 3 «Federalism», as it has more to do with states’ rights than individual rights.

The Rights

Even before the addition of the Bill of Rights, the Constitution did not ignore civil liberties entirely. It states that Congress cannot restrict one’s right to request a writ of habeas corpus A writ issued by a judge asking the government for the reasons for a person’s arrest; the Constitution protects an individual’s right to ask for such a writ. giving the reasons for one’s arrest. It bars Congress and the states from enacting bills of attainder Laws prohibited by the Constitution that punish a named individual without judicial proceedings. (laws punishing a named person without trial) or ex post facto laws Laws prohibited by the Constitution that retroactively make a legal act a crime. (laws retrospectively making actions illegal). It specifies that persons accused by the national government of a crime have a right to trial by jury in the state where the offense is alleged to have occurred and that national and state officials cannot be subjected to a “religious test,” such as swearing allegiance to a particular denomination.

The Bill of Rights contains the bulk of civil liberties. Unlike the Constitution, with its emphasis on powers and structures, the Bill of Rights speaks of “the people,” and it outlines the rights that are central to individual freedom. This section draws on Robert A. Goldwin, From Parchment to Power (Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, 1997).

The main amendments fall into several broad categories of protection:

The Bill of Rights and the National Government

Congress and the executive have relied on the Bill of Rights to craft public policies, often after public debate in newspapers. This theme is developed in Michael Kent Curtis, Free Speech, “The People’s Darling Privilege”: Struggles for Freedom of Expression in American History (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000). Civil liberties expanded as federal activities grew.

The First Century of Civil Liberties

Figure 4.1 Frederick Douglass and the North Star

The ex-slave Frederick Douglass, like many prominent abolitionists, published a newspaper. Much of the early debate over civil liberties in the United States revolved around the ability to suppress such radical statements.

The first big dispute over civil liberties erupted when Congress passed the Sedition Act in 1798, amid tension with revolutionary France. The act made false and malicious criticisms of the government—including Federalist president John Adams and Congress—a crime. While printers could not be stopped from publishing, because of freedom of the press, they could be punished after publication. The Adams administration and Federalist judges used the act to threaten with arrest and imprisonment many Republican editors who opposed them. Republicans argued that freedom of the press, before or after publication, was crucial to giving the people the information they required in a republic. The Sedition Act was a key issue in the 1800 presidential election, which was won by the Republican Thomas Jefferson over Adams; the act expired at the end of Adams’s term. See James Morton Smith, Freedom’s Fetters: The Alien and Sedition Laws and American Civil Liberties (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1956). For how the reaction to the Sedition Act produced a broader understanding of freedom of the press than the Bill of Rights intended, see Leonard W. Levy, Emergence of a Free Press (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985).

Debates over slavery also expanded civil liberties. By the mid-1830s, Northerners were publishing newspapers favoring slavery’s abolition. President Andrew Jackson proposed stopping the US Post Office from mailing such “incendiary publications” to the South. Congress, saying it had no power to restrain the press, rejected his idea. Southerners asked Northern state officials to suppress abolitionist newspapers, but they did not comply. Michael Kent Curtis, Free Speech, “The People’s Darling Privilege”: Struggles for Freedom of Expression in American History (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000), especially chaps. 6–8, quote at 189.

World War I

As the federal government’s power grew, so too did concerns about civil liberties. When the United States entered the First World War in 1917, the government jailed many radicals and opponents of the war. Persecution of dissent caused Progressive reformers to found the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in 1920. Today, the ACLU pursues civil liberties for both powerless and powerful litigants across the political spectrum. While it is often deemed a liberal group, it has defended reactionary organizations, such as the American Nazi Party and the Ku Klux Klan, and has joined powerful lobbies in opposing campaign finance reform as a restriction of speech.

The Bill of Rights and the States

The Supreme Court exercised its new power gradually. The Court followed selective incorporation Supreme Court’s application of the protections of the Bill of Rights one by one to the states after it has decided that each is “incorporated” into (inherent in) the Fourteenth Amendment’s protection of liberty against state actions. : for the Bill of Rights to extend to the states, the justices had to find that the state law violated a principle of liberty and justice that is fundamental to the inalienable rights of a citizen. Table 4.1 «The Supreme Court’s Extension of the Bill of Rights to the States» shows the years when many protections of the Bill of Rights were applied by the Supreme Court to the states; some have never been extended at all.

Table 4.1 The Supreme Court’s Extension of the Bill of Rights to the States

| Date | Amendment | Right | Case |

| 1897 | Fifth | Just compensation for eminent domain | Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad v. City of Chicago |

| 1925 | First | Freedom of speech | Gitlow v. New York |

| 1931 | First | Freedom of the press | Near v. Minnesota |

| 1932 | Fifth | Right to counsel | Powell v. Alabama (capital cases) |

| 1937 | First | Freedom of assembly | De Jonge v. Oregon |

| 1940 | First | Free exercise of religion | Cantwell v. Connecticut |

| 1947 | First | Nonestablishment of religion | Everson v. Board of Education |

| 1948 | Sixth | Right to public trial | In Re Oliver |

| 1949 | Fourth | No unreasonable searches and seizures | Wolf v. Colorado |

| 1958 | First | Freedom of association | NAACP v. Alabama |

| 1961 | Fourth | Exclusionary rule excluding evidence obtained in violation of the amendment | Mapp v. Ohio |

| 1962 | Eighth | No cruel and unusual punishment | Robinson v. California |

| 1963 | First | Right to petition government | NAACP v. Button |

| 1963 | Fifth | Right to counsel (felony cases) | Gideon v. Wainwright |

| 1964 | Fifth | Immunity from self-incrimination | Mallory v. Hogan |

| 1965 | Sixth | Right to confront witnesses | Pointer v. Texas |

| 1965 | Fifth, Ninth, and others | Right to privacy | Griswold v. Connecticut |

| 1966 | Sixth | Right to an impartial jury | Parker v. Gladden |

| 1967 | Sixth | Right to a speedy trial | Klopfer v. N. Carolina |

| 1969 | Fifth | Immunity from double jeopardy | Benton v. Maryland |

| 1972 | Sixth | Right to counsel (all crimes involving jail terms) | Argersinger v. Hamlin |

| 2010 | Second | Right to keep and bear arms | McDonald v. Chicago |

| Rights not extended to the states | |||

| Third | No quartering of soldiers in private dwellings | ||

| Fifth | Right to grand jury indictment | ||

| Seventh | Right to jury trial in civil cases under common law | ||

| Eighth | No excessive bail | ||

| Eighth | No excessive fines | ||

Interests, Institutions, and Civil Liberties

Many landmark Supreme Court civil-liberties cases were brought by unpopular litigants: members of radical organizations, publishers of anti-Semitic periodicals or of erotica, religious adherents to small sects, atheists and agnostics, or indigent criminal defendants. This pattern promotes a media frame suggesting that civil liberties grow through the Supreme Court’s staunch protection of the lowliest citizen’s rights.

The finest example is the saga of Clarence Gideon in the book Gideon’s Trumpet by Anthony Lewis, then the Supreme Court reporter for the New York Times. The indigent Gideon, sentenced to prison, protested the state’s failure to provide him with a lawyer. Gideon made a series of handwritten appeals. The Court heard his case under a special procedure designed for paupers. Championed by altruistic civil-liberties experts, Gideon’s case established a constitutional right to have a lawyer provided, at the state’s expense, to all defendants accused of a felony. Anthony Lewis, Gideon’s Trumpet (New York: Vintage Books, 1964). Similar storylines often appear in news accounts of Supreme Court cases. For example, television journalists personalize these stories by interviewing the person who brought the suit and telling the touching individual tale behind the case. Richard Davis, Decisions and Images: The Supreme Court and the News Media (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1994).

This mass-media frame of the lone individual appealing to the Supreme Court is only part of the story. Powerful interests also benefit from civil-liberties protections. Consider, for example, freedom of expression: Fat-cat campaign contributors rely on freedom of speech to protect their right to spend as much money as they want to in elections. Advertisers say that commercial speech should be granted the same protection as political speech. Huge media conglomerates rely on freedom of the press to become unregulated and more profitable. Frederick Schauer, “The Political Incidence of the Free Speech Principle,” University of Colorado Law Review 64 (1993): 935–57.

Many officials have to interpret the guarantees of civil liberties when making decisions and formulating policy. They sometimes have a broader awareness of civil liberties than do the courts. For example, the Supreme Court found in 1969 that two Arizona newspapers violated antitrust laws by sharing a physical plant while maintaining separate editorial operations. Congress and the president responded by enacting the Newspaper Preservation Act, saying that freedom of the press justified exempting such newspapers from antitrust laws.

Key Takeaways

In this section we defined civil liberties as individual rights and freedoms that government may not infringe on. They are listed primarily in the Bill of Rights, the ten amendments added in 1791 by the founders to address fears about the new federal government’s potential to abuse power. Initially limited to the federal government, they now apply, though unevenly, to the states. What those liberties are and how far they extend are the focus of political conflict. They are shaped by the full range of people, processes, and institutions in American politics. Both unpopular minorities and powerful interests claim civil liberties protections to gain favorable outcomes.

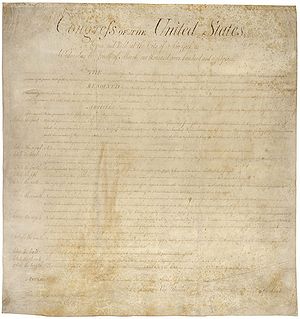

United States Bill of Rights

Articles of the Constitution

I ∙ II ∙ III ∙ IV ∙ V ∙ VI ∙ VII

I ∙ II ∙ III ∙ IV ∙ V ∙ VI ∙ VII ∙ VIII ∙ IX ∙ X

Subsequent Amendments

XI ∙ XII ∙ XIII ∙ XIV ∙ XV ∙ XVI

XVII ∙ XVIII ∙ XIX ∙ XX ∙ XXI ∙ XXII

XXIII ∙ XXIV ∙ XXV ∙ XXVI ∙ XXVII

The United States Bill of Rights consists of the first 10 amendments to the United States Constitution. These amendments limit the powers of the federal government, protecting the rights of all citizens, residents and visitors on United States territory. Among the enumerated rights these amendments guarantee are: the freedoms of speech, press, and religion; the people’s right to keep and bear arms; the freedom of assembly; the freedom to petition; and the rights to be free of unreasonable search and seizure; cruel and unusual punishment; and compelled self-incrimination.

The Bill of Rights also restricts Congress’ power by prohibiting it from making any law respecting establishment of religion and by prohibiting the federal government from depriving any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. In criminal cases, it requires indictment by grand jury for any capital or «infamous crime,» guarantees a speedy public trial with an impartial and local jury, and prohibits double jeopardy. In addition, the Bill of Rights Ninth Amendment states that «the enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people,» and reserves all powers not granted to the Federal government to the citizenry or States.

Contents

These amendments went into effect on December 15, 1791, when ratified by three-fourths of the States. Most were applied to the states by a series of decisions applying the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which was adopted after the American Civil War. The U. S. Bill of Rights represented a major step in the creation of democracy in defining the roles and responsibilities of the government vis-a-vis the citizenry.

| Founding Documents of the United States |

|---|

| Declaration of Independence (1776) |

| Articles of Confederation (1777) |

| Constitution (1787) |

| Bill of Rights (1789) |

Background

Initially drafted by James Madison in 1789, the Bill of Rights was written at a time when ideological conflict between Federalists and anti-Federalists, dating from the Philadelphia Convention in 1787, threatened the Constitution’s ratification. The Bill was influenced by George Mason’s 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights, the 1689 English Bill of Rights, works of the Age of Enlightenment pertaining to natural rights, and earlier English political documents such as the Magna Carta (1215). The Bill was largely a response to the Constitution’s influential opponents, including prominent Founding Fathers, who argued that it failed to protect the basic principles of human liberty.

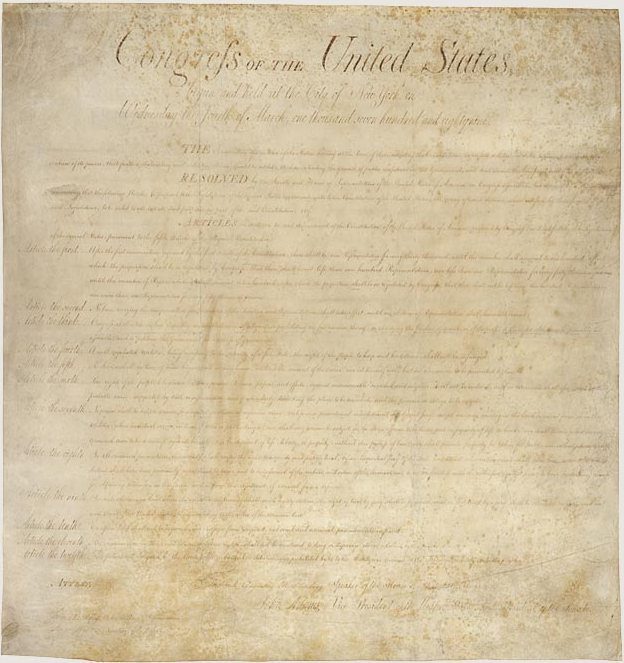

The Bill of Rights plays a central role in American law and government, and remains a fundamental symbol of the freedoms and culture of the nation. One of the original fourteen copies of the Bill of Rights is on public display at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

The original document proposed by Congress to the states actually contained 12 «Articles» of proposed amendment. However, only the third through twelfth articles, corresponding to what became the First through Tenth Amendments to the Constitution, were ratified by the required number of states by 1791. The first Article, dealing with the number and apportionment of members of the House of Representatives, never became part of the Constitution. The second Article, limiting the ability of Congress to increase the salaries of its members, was ratified two centuries later as the 27th Amendment. The term «Bill of Rights» has traditionally meant only the 10 amendments that became part of the Constitution in 1791, and not the first two, which dealt with Congress itself rather than the rights of the people. That traditional usage has continued even since the ratification of the 27th Amendment.

History

The Philadelphia Convention set out to correct weaknesses inherent in the Articles of Confederation that had been apparent even before the American Revolutionary War had been successfully concluded. The newly constituted Federal government included a strong executive branch, a stronger legislative branch and an independent judiciary.

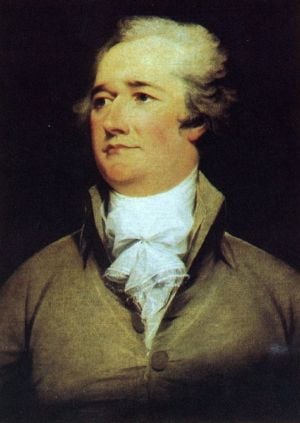

Arguments against the Bill of Rights

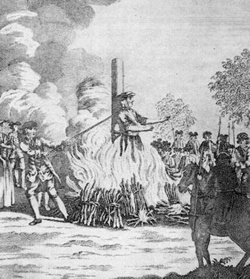

The idea of adding a bill of rights to the Constitution was originally controversial. Alexander Hamilton, in Federalist No. 84, argued against a «Bill of Rights,» asserting that ratification of the Constitution did not mean the American people were surrendering their rights, and therefore that protections were unnecessary: «Here, in strictness, the people surrender nothing, and as they retain every thing, they have no need of particular reservations.» As critics of the Constitution referred to earlier political documents that had protected specific rights, Hamilton argued that the Constitution was inherently different. Unlike previous political arrangements between sovereigns and subjects, in the United States there would be no agent empowered to abridge the people’s rights:

«Bills of rights are in their origin, stipulations between kings and their subjects, abridgments of prerogative in favor of privilege, reservations of rights not surrendered to the prince. Such was Magna Charta, obtained by the Barons, sword in hand, from King John.» [1]

Finally, Hamilton expressed the fear that protecting specific rights might imply that any unmentioned rights would not be protected:

«I go further, and affirm that bills of rights, in the sense and in the extent in which they are contended for, are not only unnecessary in the proposed constitution, but would even be dangerous. They would contain various exceptions to powers which are not granted; and on this very account, would afford a colorable pretext to claim more than were granted. For why declare that things shall not be done which there is no power to do?»

Essentially, Hamilton and other Federalists believed in the British system of common law which did not define or quantify natural rights. They believed that adding a Bill of Rights to the Constitution would limit their rights to those listed in the Constitution. This is the primary reason the Ninth Amendment was included.

The Anti-Federalists

During the debate over the ratification of the Constitution, famous revolutionary figures such as Patrick Henry came out publicly against the Constitution. [3] They argued that the strong national government proposed by the Federalists was a threat to individual rights and that the President would become a king, and objected to the federal court system in the proposed Constitution. Thomas Jefferson, ambassador to France, described his concern over the lack of a Bill of Rights, among other criticisms. In answer to the argument that a list of rights might be interpreted as being exhaustive, Jefferson wrote to Madison:

«Half a loaf is better than no bread. If we cannot secure all our rights, let us secure what we can.» March 15, 1789 [4]

The best and most influential of the articles and speeches criticizing the Constitution were gathered by historians into a collection known as the Anti-Federalist papers, an allusion to the Federalist Papers which had supported the creation of a stronger federal government. One of these, an essay «On the lack of a Bill of Rights,» later called «Antifederalist No. 84,» was written under the pseudonym «Brutus,» probably by Robert Yates. In response to the Federalist view that it was unnecessary to protect the people against powers that the government would not be granted, «Brutus» wrote:

«We find they have, in the ninth section of the first article declared, that the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless in cases of rebellion—that no bill of attainder, or ex post facto law, shall be passed—that no title of nobility shall be granted by the United States, etc. If every thing which is not given is reserved, what propriety is there in these exceptions? Does this Constitution any where grant the power of suspending the habeas corpus, to make ex post facto laws, pass bills of attainder, or grant titles of nobility? It certainly does not in express terms. The only answer that can be given is, that these are implied in the general powers granted. With equal truth it may be said, that all the powers which the bills of rights guard against the abuse of, are contained or implied in the general ones granted by this Constitution.» [5] [6]

Yates continued with an implication directed against the Framers:

Ought not a government, vested with such extensive and indefinite authority, to have been restricted by a declaration of rights? It certainly ought. So clear a point is this, that I cannot help suspecting that persons who attempt to persuade people that such reservations were less necessary under this Constitution than under those of the States, are willfully endeavoring to deceive, and to lead you into an absolute state of vassalage. [7]

Ratification and the Massachusetts Compromise

Individualism was the strongest element of opposition; the necessity, or at least the desirability, of a bill of rights was almost universally felt, and the Anti-Federalists were able to play on these feelings in the ratification convention in Massachusetts. By this stage, five of the states had ratified the Constitution with relative ease; however, the Massachusetts convention was bitter and contentious. «In Massachusetts, the Constitution ran into serious, organized opposition,» wrote historian Richard Bernstein:

Only after two leading Antifederalists, Adams and Hancock, negotiated a far-reaching compromise did the convention vote for ratification on February 6, 1788 (187–168). Antifederalists had demanded that the Constitution be amended before they would consider it or that amendments be a condition of ratification; Federalists had retorted that it had to be accepted or rejected as it was. Under the Massachusetts compromise, the delegates recommended amendments to be considered by the new Congress, should the Constitution go into effect. The Massachusetts compromise determined the fate of the Constitution, as it permitted delegates with doubts to vote for it in the hope that it would be amended. [8]

Four of the next five states to ratify, including New Hampshire, Virginia, and New York, included similar language in their ratification instruments. They all sent recommendations for amendments with their ratification documents to the new Congress. Since many of these recommendations pertained to safeguarding personal rights, this pressured Congress to add a Bill of Rights after Constitutional ratification. Additionally, North Carolina refused to ratify the Constitution until progress was made on the issue of the Bill of Rights. Thus, while the Anti-Federalists were unsuccessful in their quest to prevent the adoption of the Constitution, their efforts were not totally in vain.

After the Constitution was ratified in 1789, the 1st United States Congress met in Federal Hall in New York City. Most of the delegates agreed that a «bill of rights» was needed and most of them agreed on the rights they believed should be enumerated.

Madison, at the head of the Virginia delegation of the 1st Congress, had opposed a Bill of Rights but hoped to preempt a second Constitutional Convention that might have undone the difficult compromises of 1787: a second convention would open the entire Constitution to reconsideration and could undermine the work he and so many others had done in establishing the structure of the United States Government.

Madison based much of the Bill of Rights on George Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776), which itself had been written with Madison’s input. He carefully considered the state amendment recommendations as well. He looked for recommendations shared by many states to avoid controversy and reduce opposition to the ratification of the future amendments. Additionally, Madison’s work on the Bill of Rights reflected centuries of English law and philosophy, further modified by the principles of the American Revolution. The English legal tradition included such revolutionary documents as the Magna Carta (1215), protecting the rights of noblemen against the King of England, and the English Bill of Rights (1689), establishing the rights of legislators in Parliament against the power of the sovereign. Concurrently, English philosopher John Locke had argued that all men have inalienable natural rights and that the purpose of government was to protect property rights, ideas that became part of the American view of government. Madison, in the United States Bill of Rights, continued in the radical tradition of the American Revolution by further extending and codifying these rights.

Antecedents

To some degree, the Bill of Rights (and the American Revolution) incorporated the ideas of John Locke, who argued in his 1689 work Two Treatises of Government that civil society was created for the protection of property (Latin proprius, or that which is one’s own, meaning «life, liberty, and estate»). Locke also advanced the notion that each individual is free and equal in the state of nature. Locke expounded on the idea of natural rights that are inherent to all individuals, a concept Madison mentioned in his speech presenting the Bill of Rights to the 1st Congress.

The Virginia Declaration of Rights, [9] well-known to Madison, had already been a strong influence on the American Revolution («all power is vested in, and consequently derived from, the people …»; [10] also «a majority of the community hath an indubitable, unalienable, and indefeasible right to reform, alter or abolish [the government]»). It had shaped the drafting of the United States Declaration of Independence a decade before the drafting of the Constitution, proclaiming that «all men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights of which … [they cannot divest;] namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.» [11] On a practical level, its recommendations of a government with a separation of powers (Articles 5–6) and «frequent, certain, and regular» [12] elections of executives and legislators were incorporated into the United States Constitution—but the bulk of this work addresses the rights of the people and restrictions on the powers of government, and is recognizable in the modern Bill of Rights:

The government should not have the power of suspending or executing laws, «without consent of the representatives of the people,». [13] A legal defendant has the right to be «confronted with the accusers and witnesses, to call for evidence in his favor, and to a speedy trial by an impartial jury of his vicinage,» and may not be «compelled to give evidence against himself.» [14] Individuals should be protected against «cruel and unusual punishments», [15] baseless search and seizure, [16] and be guaranteed a trial by jury. [17] The government should not abridge freedom of the press, [18] or freedom of religion («all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion»). [19] The government should be enjoined against maintaining a standing army rather than a «well regulated militia.» [20]

The English Bill of Rights (1689), one of the fundamental documents of English law, differed substantially in form and intent from the American Bill of Rights, because it was intended to address the rights of citizens as represented by Parliament against the Crown. However, some of its basic tenets are adopted and extended to the general public by the U.S. Bill of Rights, including:

Madison’s preemptive proposal

On June 8 1789, Madison submitted his proposal to Congress. In his speech to Congress on that day, Madison said,

For while we feel all these inducements to go into a revisal of the constitution, we must feel for the constitution itself, and make that revisal a moderate one. I should be unwilling to see a door opened for a re-consideration of the whole structure of the government, for a re-consideration of the principles and the substance of the powers given; because I doubt, if such a door was opened, if we should be very likely to stop at that point which would be safe to the government itself: But I do wish to see a door opened to consider, so far as to incorporate those provisions for the security of rights, against which I believe no serious objection has been made by any class of our constituents. [21]

Prior to listing his proposals for a number of constitutional amendments, Madison acknowledged a major reason for some of the discontent with the Constitution as written:

I believe that the great mass of the people who opposed [the Constitution], disliked it because it did not contain effectual provision against encroachments on particular rights, and those safeguards which they have been long accustomed to have interposed between them and the magistrate who exercised the sovereign power: nor ought we to consider them safe, while a great number of our fellow citizens think these securities necessary. [21]

Ratification process

On November 20 1789, New Jersey became the first state to ratify these amendments. On December 15 1791, ten of these proposals became the First through Tenth Amendments—and United States law—when they were ratified by the Virginia legislature.

Articles III to XII were ratified by 11 out of 14 states (greater than 75 percent). Article I, (rejected by Delaware), was ratified only by 10 of 14 States (less than 75 percent), and despite later ratification by Kentucky (11 of 15 states, which would have made the vote less than 75 percent, the article has never since received the approval of enough states for it to become part of the Constitution. Article II was ratified by 6 of 14, later 7 of 15 states, but did not receive the three quarters majority of States needed for ratification until 1992 when it became the 27th Amendment.

Ratification dates

Later consideration

Lawmakers in Kentucky, which became the 15th state to join the Union in June 1792, ratified the entire set of 12 proposals during that commonwealth’s initial month of statehood, perhaps unaware—given the nature of long-distance communications in the 1700s—that Virginia’s approval six months earlier had already made 10 of the 12 amendments part of the Constitution.

Although ratification made the Bill of Rights effective in 1791, three of the original 13 states—Connecticut, Georgia, and Massachusetts—did not «ratify» the first 10 amendments until 1939, when they were urged to do so in a celebration of the 150th anniversary of their passage by Congress. [22]

Incorporation extends to States

Originally, the Bill of Rights applied only to the federal government and not to the several state governments. Parts of the amendments initially proposed by Madison that would have limited state governments («No state shall violate the equal rights of conscience, or the freedom of the press, or the trial by jury in criminal cases.») [21] were not approved by Congress, and therefore the Bill of Rights did not appear to apply to the powers of state governments.

Thus, states had established state churches up until the 1820s, and Southern states, beginning in the 1830s, could ban abolitionist literature. In the 1833 case Barron v. Baltimore, the Supreme Court specifically ruled that the Bill of Rights provided «security against the apprehended encroachments of the general government—not against those of local governments.» However, in the 1925 judgment on Gitlow v. New York, the Supreme Court ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment, which had been adopted in 1868, made certain applications of the Bill of Rights applicable to the states. The Supreme Court then cited the Gitlow case as precedent for a series of decisions that made most, but not all, of the provisions of the Bill of Rights applicable to the states under the doctrine of selective incorporation.

Display and honoring of the Bill of Rights

In 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared December 15 to be «Bill of Rights Day,» commemorating the 150th anniversary of the ratification of the Bill of Rights.

The Bill of Rights is on display at the National Archives and Records Administration, in the «Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom.»

The Rotunda itself was constructed in the 1950s and dedicated in 1952 by President Harry S. Truman, who stated: «Only as these documents are reflected in the thoughts and acts of Americans, can they remain symbols of power that can move the world. That power is our faith in human liberty.» [23]

After 50 years, signs of deterioration in the casing were noted, while the documents themselves appeared to be well-preserved: «But if the ink of 1787 was holding its own, the encasements of 1951 were not… minute crystals and microdroplets of liquid were found on surfaces of the two glass sheets over each document…. The CMS scans confirmed evidence of progressive glass deterioration, which was a major impetus in deciding to re-encase the Charters of Freedom.» [24]

Accordingly, the casing was updated and the Rotunda rededicated on September 17, 2003. In his dedicatory remarks, 216 years after the close of the Constitutional Convention, President George W. Bush stated, «The true [American] revolution was not to defy one earthly power, but to declare principles that stand above every earthly power—the equality of each person before God, and the responsibility of government to secure the rights of all.» [25]

In 1991, the Bill of Rights toured the country in honor of its bicentennial, visiting the capitals of all 50 states.

Text of the Bill of Rights

Preamble

The Preamble to the Bill of Rights:

Congress of the United States begun and held at the City of New-York, on Wednesday the fourth of March, one thousand seven hundred and eighty nine.

THE Conventions of a number of the States, having at the time of their adopting the Constitution, expressed a desire, in order to prevent misconstruction or abuse of its powers, that further declaratory and restrictive clauses should be added: And as extending the ground of public confidence in the Government, will best ensure the beneficent ends of its institution.

RESOLVED by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America, in Congress assembled, two thirds of both Houses concurring, that the following Articles be proposed to the Legislatures of the several States, as amendments to the Constitution of the United States, all, or any of which Articles, when ratified by three fourths of the said Legislatures, to be valid to all intents and purposes, as part of the said Constitution; viz.

ARTICLES in addition to, and Amendment of the Constitution of the United States of America, proposed by Congress, and ratified by the Legislatures of the several States, pursuant to the fifth Article of the original Constitution. [26]

Amendments

Notes

References

External links

All links retrieved June 1, 2022.

| United States Constitution | |

|---|---|

| Formation | History • Articles of Confederation • Annapolis Convention • Philadelphia Convention • New Jersey Plan • Virginia Plan • Connecticut Compromise • Signatories • Massachusetts Compromise • Federalist Papers |

| Amendments | Bill of Rights • Ratified • Proposed • Unsuccessful • Conventions to propose • State ratifying conventions |

| Clauses | Appointments • Case or controversy • Citizenship • Commerce • Confrontation • Contract • Copyright • Due Process • Equal Protection • Establishment • Exceptions • Free Exercise • Full Faith and Credit • Impeachment • Natural–born citizen • Necessary and Proper • No Religious Test • Presentment • Privileges and Immunities (Art. IV) • Privileges or Immunities (14th Amend.) • Speech or Debate • Supremacy • Suspension • Takings Clause • Taxing and Spending • Territorial • War Powers |

| Interpretation | Theory • Congressional enforcement • Double jeopardy • Dormant commerce clause • Enumerated powers • Executive privilege • Incorporation of the Bill of Rights • Nondelegation • Preemption • Separation of church and state • Separation of powers |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

The Bill of Rights

The Bill of Rights is the First Ten Amendments to the US Constitution. These amendments were passed all at once by the First United States Congress in 1791. These Amendments are a very important part of the Constitution that protect certain rights of American citizens from being violated by the government, rights such as freedom of religion, freedom to bear arms, freedom of the press and the right to trial by jury.

The Bill of Rights played a very important part in the passing of the Constitution in the first place. When the Constitution was first proposed, many individuals and state conventions were concerned that it did not adequately protect the rights of the citizens. Because of this, many people were against the Constitution as it was written. Several state governments decided they would vote to accept the Constitution only if a Bill of Rights was added. A Bill of Rights is a clearly spelled out list of the rights of the people that the government cannot meddle with.

In the end, it was agreed that the Constitution would be accepted as it was written, with the promise that the First Congress would examine the various proposed amendments and would add the best ones to the constitution to cover these concerns. All amendments had to be passed by 3/4 of the states to be added to the Constitution, so this process ensured that the people’s concerns about their rights would be addressed.

The states passed ten amendments that became law on December 15, 1791. These Ten Amendments are also known as the Bill of Rights. You can read the Bill of Rights here or find brief overviews of the history, purpose and sections of the Bill of Rights on this page, with links to more in depth information.

Purpose of the Bill of Rights

The American Bill of Rights was introduced because of arguments that arose against the newly proposed US Constitution when it was first introduced. The Bill of Rights served two primary purposes, to define a list of specific individual rights that the government could not encroach upon and to alleviate the fears of the Constitution’s detractors so they would support it.

After the Constitutional Convention produced the Constitution, it was sent to the states for their review. Each state formed its own Constitutional Convention to accept or reject the Constitution. They were known as «ratification» conventions, because to «ratify» means to accept.

A lengthy debate began in each colony about the merits of the Constitution. The Constitution’s supporters were known as Federalists, because they supported a strong central government. The Federalists were led by such men as James Madison, Alexander Hamilton and John Jay. The Constitution’s detractors were known as anti-Federalists. They believed the Constitution gave too much power to the central government at the expense of the states and individuals and were led by such men as Patrick Henry, George Mason and Elbridge Gerry.

Most people agreed that a stronger government was needed. Since the end of the Revolutionary War, the country had been governed by the Articles of Confederation, which created a very weak central government that turned out to be so weak that it couldn’t raise revenue, support troops, enforce laws or even require its legislators to meet.

This was the reason for the creation of the Constitution, to create a new, stronger government to replace the weak one under the Articles of Confederation. Once it was decided to make a stronger government, however, the citizens still had to decide how strong they wanted this government to be.

To alleviate the fears of the anti-Federalists, the pro-Constitution forces promised that the First Congress would add a Bill of Rights to the Constitution if they would go ahead and accept it. This promise persuaded enough anti-Federalists to support the Constitution that it finally passed.

You can learn more about the purpose of this important document at our Purpose of the Bill of Rights page.

Passage of the Bill of Rights

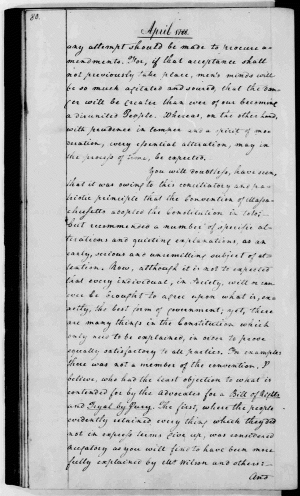

The First Congress began its session in March of 1789. On June 8, James Madison, the chief author of the Constitution, gave a speech to Congress in which he submitted 20 of the most requested amendments for consideration. You can read James Madison’s June 8, 1789 speech here.

Congress debated these and eventually chose twelve amendments to send to the states for ratification. Each state then considered each of the amendments. 3/4 of the states had to pass each amendment in order for it to become part of the Constitution. Eventually, ten of them were accepted by the states and these have become known as the Bill of Rights. They became law with Virginia’s ratification on December 15, 1791.

You can learn much more about the creation of the Bill of Rights at our history of the Bill of Rights page here.

Picture of the Bill of Rights

View a history of the Bill of Rights in pictures at our Bill of Rights Pictures page. You will see the original Bill of Rights that is now housed at the National Archives.

We also have pictures of letters from George Washington and James Madison revealing their opinions about the Bill of Rights.

You can see Madison’s handwritten notes he used to give his June 8, 1791 speech in which he introduced 20 amendments to be considered by Congress, as well as his original copy of the Bill of Rights.

After the Bill of Rights was passed, President George Washington had thirteen handwritten copies made for each of the thirteen states. Several of these copies are still in existence today and can be seen here.

Take a look at all of these fascinating images at our Bill of Rights Pictures page here.

The First Amendment

The First Amendment is one of the most well known parts of the US Constitution. It forbids the Congress from making any.

law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

If it weren’t for the First Amendment, politicians could dictate to you how you could or could not express faith in God, what you could say or could not say in public and who you could or could not gather together with. It is a bedrock of the freedoms enjoyed in this country.

The Bill of Rights was added to the Constitution by the First Congress to ensure that the government would never encroach upon the listed rights of the people. The general attitude of the Founding Fathers was that human rights were not granted by the government, but protected by the government. The rights themselves came from God as a gift to humans by virtue of their being human.

First Ten Amendments

The First Ten Amendments are collectively known as the Bill of Rights. Each amendment covers various rights that are guaranteed to American citizens, including freedom of religion, freedom to assemble, freedom from cruel and unusual punishment and freedom not to incriminate oneself at trial. You can read more about each of these First Ten Amendments and the rights they protect here.

1st Amendment

The 1st Amendment protects the rights of freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly and freedom to petition the government. Without this right, the government could tell people how and when to pray, what religion they must follow, what they can or cannot say, who they can gather together with, what they can publish or broadcast and could refuse to listen to their grievances.

2nd Amendment

The 2nd Amendment guarantees the «right of the people to keep and bear arms.»

The 2nd Amendment is highly valued by Americans who want to hunt or protect themselves in case of danger. The right to bear arms was very important to the Founding Fathers because they did not want the government to overpower the citizens if the government should become corrupt. If citizens were not allowed to own their own guns, they could easily be controlled and enslaved by the government.

In recent years, the meaning of the 2nd Amendment has been debated vehemently. Some people believe the Amendment was only meant to allow the states to form their own militias for purposes of defense and that it has nothing to do with individuals owning guns for other purposes.

Others believe the 2nd Amendment grants all citizens the right to have guns under any circumstances. Some recent court decisions have created limitations on the ability to own guns, such as those that create zones where guns may not be carried or require licensing, classes or background checks to own a gun.

You can learn more about the history and meaning of the 2nd Amendment here.

3rd Amendment

The 3rd Amendment forbids the government from quartering troops on the private property of individuals. Prior to the Revolutionary War, the British government had passed the Quartering Act of 1765 and the Quartering Act of 1774, which required private citizens to house soldiers on their property if there were no public accommodations available.

This was one of the grievances listed by Thomas Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence. In addition, the Quartering Acts required private citizens to provide food for any soldiers staying on their property.

The 3rd Amendment guarantees the government will not house troops on private property during peacetime and only as prescribed by law during times of war.

The 3rd Amendment is one of the least familiar to Americans today because so few wars have been fought on American territory and because the American army is housed on large military bases.

You can learn more about the history and meaning of the 3rd Amendment here.

4th Amendment

The 4th Amendment protects American citizens from illegal searches and seizures of their private property and requires that a warrant be issued in order for a government official to search or seize private property.

The 4th Amendment had its origins in the British «writs of assistance» that were used by colonial officials to search for smuggled contraband. The colonists had a habit of trying to evade customs taxes on imported goods because the taxes were so high. In response, the customs officials would get a «writ of assistance,» which gave them authority to search any private property, any time they wanted.

This greatly angered the colonists and was one of their chief grievances against the Crown. When the Bill of Rights was added to the Constitution, the citizens wanted their rights spelled out very clearly when it came to searches, seizures of private property and warrants.

The 4th Amendment generally requires that in order for a search to be conducted of private property, a warrant must be issued by a judge and only when there has been probable cause demonstrated that a crime has been committed. There are some exceptions, but generally speaking, if evidence of a crime is obtained outside of this process, the search and seizure is illegal and the evidence is not admissible in court.

Learn more about the history and protections of the 4th Amendment here. Read about some of the most significant 4th Amendment Court Cases here.

5th Amendment

The 5th Amendment is one of the most important of the amendments listed in the Bill of Rights and is also one of the most familiar to Americans due to the phrase «I plead the Fifth,» which is a defense often used in criminal trials.

The 5th Amendment protects several different rights, including:

You can read more about the history, meaning and purpose of the 5th Amendment here.

6th Amendment

Of the 26 rights guaranteed in the first 8 amendments of the Bill of Rights, 15 of them have to do with the rights of those accused of a committing a crime. British history included a long history of false accusations for political and religious differences. People were often charged and punished unfairly for things they didn’t do if they were in disagreement with the authorities. People had been imprisoned, tortured and even killed for things as simple as choosing a different religion than the king or speaking out against a government official.

The 6th Amendment guarantees the accused of 7 specific rights:

Learn more about the history, purpose and meaning of the 6th Amendment here.

7th Amendment

The 7th Amendment guarantees the right to trial by jury in civil cases, while the 6th Amendment guarantees the same right in criminal cases. The same right is guaranteed in the case of an infamous crime, or felony, in the 5th Amendment. The right to trial by jury was clearly important to the Founding Fathers, or they would not have mentioned it so many times in the Bill of Rights.

The colonists had gone through a period of being denied the right to trial by jury under the British Crown. Due to high taxation and trade laws, colonists were heavily engaged in smuggling. Officials began to try and convict more and more colonists for their smuggling operations, but colonial juries frequently acquitted the accused smugglers, even if they blatantly violated the law. This caused the King to set up new courts without juries, so they could not undermine the convictions. This gave an enormous amount of power to judges who often had personal motives to convict the accused, such as earning a percentage of the judgement against them, or to earn favor and promotion in the eyes of the crown.

The Founding Fathers saw trial by jury as a defense against just such corrupt government officials. In a trial by jury, a group of the accused’s own peers would make the determination of guilt or innocence, rather than one individual in the employment of the government. The accused’s neighbors and peers are likely to have similar interests and beliefs as the accused person. The possibility for corruption is much less likely with a jury trial than if the decision lies in the hands of a single judge, who may have personal motives against the accused or an agenda he wishes to promote.

Learn more about the history, meaning and purpose of the 7th Amendment here.

8th Amendment

The 8th Amendment to the Constitution protects three rights for all Americans. It requires that:

The Excessive Bail Clause

Bail is paid by an accused defendant in order to get out of jail before the date of his trial. If the defendant shows up for his trial, the bail money is returned to him, but if he fails to show up for his trial, he forfeits the money.

Bail must be set sufficiently high that the accused person has an incentive to show up for trial so he does not lose his money, but it cannot be set so high that it is an unreasonable amount.

This was important to the Founding Fathers due to instances in British history when judges required such high bail that there was no way accused people could pay it. Judges often did this to punish people with different political beliefs than their own.

The Excessive Fines Clause

The Courts will not allow fines that are grossly disproportional to the seriousness of the offense. Even so, higher courts rarely overturn the decision of a lower court where fines are concerned. This is one of the least used provisions of the Bill of Rights. In fact, the Supreme Court never overturned a case for violating the Excessive Fines Clause until 1998.

The Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause

Great Britain had a long and terrible history of cruel and unusual punishments inflicted on convicted criminals, things such as burning at the stake, chopping off body parts, crucifixion, castration, breaking on the wheel and so on. America’s Founding Fathers wanted to make sure no such punishments were inflicted in the United States.

In general, a punishment is considered to be cruel and unusual if the majority of the public would deem it to be so, but if the majority of the public approves of a certain type of punishment, it is usually allowed. The Supreme Court has stated, based on this clause, that punishments must be in proportionality to the crime committed.

Over time, the Court’s definition of «cruel and unusual» has changed. For example, the death penalty was allowed in all of the original 13 states for crimes other than murder, but today, it is not allowed for crimes other than murder or treason. It is also not allowed if the guilty was younger than the age of 18 or mentally incompetent at the time of the crime.

Death by lethal injection, hanging, the firing squad and by the electric chair are still allowed today.

You can learn more about the history and meaning of the 8th Amendment here. You can also read about some of the most influential and important 8th Amendment Court Cases here.

9th Amendment

The 9th Amendment is one of the least referred to amendments in the Bill of Rights. It is also probably one of the most important and controversial. The 9th Amendment says, «The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.»

In plain language, it means that although the Constitution lists certain rights of the people that may not be violated by the government, there are also other rights of the people that are not listed, that the government may not violate either.

The Founding Fathers believed that man inherently has natural rights by virtue of his being human and that the government should not violate those rights. They also thought it was impossible for them to list all such rights. Instead, they addressed some of the most important in the Constitution, but left the States to determine the rest, as is spelled out in the 10th Amendment.

The problem is that the modern Supreme Court has taken it upon itself to determine what those extra, unlisted rights are and the States and the people have not challenged the Court in this endeavor.

Today, a small handful of unelected judges often throws out the laws passed by the people through their legislatures in the name of «protecting civil rights.» In reality, the Courts often violate the will of the people by throwing out their laws and forcing their own will upon the people. This is a source of much contention in modern political debate.

You can learn more about the history, meaning and purpose of the 9th Amendment here.

10th Amendment

The 10th Amendment reserves any rights not granted to the Federal Government in the Constitution to the states. The Founding Fathers were extremely concerned that the government not be too powerful. After all, they had just fought a war to get rid of a tyrannical government.

They created a government which listed the specific responsibilities of each branch of government. The Bill of Rights was added to further specify the rights the government could not encroach upon. The Founders wanted local governments to make most decisions in their lives because local governments would be easier for the people to control. Consequently, the 10th Amendment says that any powers not specifically given to the federal government were reserved to the states.

In recent years, through a set of gradual changes, this right of the states has been largely abandoned. The Courts and Congress have taken the initiative to legislate in many areas that were once reserved to the states. This all began around the time of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the New Deal programs, which created many federal jobs to help people get through the Great Depression. The New Deal jobs programs caused many people to look to the government to play a larger role in their lives than it had before. Since then, that role has grown larger and larger.

You can learn more about the history and purpose of the 10th Amendment here.

Read the Bill of Rights

It is important for Americans to understand their rights that are protected by the Constitution. If you do not know what rights you have that are not to be violated by the government, you could easily have these rights taken away by slick tongued politicians. A good place to start is by actually reading the Bill of Rights and understanding the protections it provides. You can read the Bill of Rights here. It will only take you a few minutes. It’s not very long!

Amendments:

Learn more about the Bill of Rights with the following articles:

English Bill of Rights

Contents

The English Bill of Rights was an act signed into law in 1689 by William III and Mary II, who became co-rulers in England after the overthrow of King James II. The bill outlined specific constitutional and civil rights and ultimately gave Parliament power over the monarchy. Many experts regard the English Bill of Rights as the primary law that set the stage for a constitutional monarchy in England. It’s also credited as being an inspiration for the U.S. Bill of Rights.

Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, which took place in England from 1688-1689, involved the ousting of King James II.

Both political and religious motives sparked the revolution. Many English citizens were distrustful of the Catholic king and disapproved of the monarchy’s outright power.

Tensions were high between Parliament and the king, and Catholics and Protestants were also at odds.

James II was eventually replaced by his Protestant daughter, Mary, and her Dutch husband, William of Orange. The two leaders formed a joint monarchy and agreed to give Parliament more rights and power.

Part of this settlement included signing the English Bill of Rights, which was formally known as “An Act Declaring the Rights and Liberties of the Subject and Settling the Succession of the Crown.”

Among its many provisions, the Bill of Rights condemned King James II for abusing his power and declared that the monarchy could not rule without consent of the Parliament.

What’s in the Bill of Rights?

The English Bill of Rights includes the following items:

In general, the Bill of Rights limited the power of the monarchy, elevated the status of Parliament and outlined specific rights of individuals.

Some of the key liberties and concepts laid out in the articles include:

Other important provisions were that Roman Catholics couldn’t be king or queen, Parliament should be summoned frequently and the succession of the throne would be passed to Mary’s sister, Princess Anne of Denmark and her heirs (than to any heirs of William by a later marriage).

Recommended for you

8 Fascinating Facts About Ancient Roman Medicine

What Caused Ancient Egypt’s Decline?

The 6 Earliest Human Civilizations

Constitutional Monarchy

The English Bill of Rights created a constitutional monarchy in England, meaning the king or queen acts as head of state but his or her powers are limited by law.

Under this system, the monarchy couldn’t rule without the consent of Parliament, and the people were given individual rights. In the modern-day British constitutional monarchy, the king or queen plays a largely ceremonial role.

An earlier historical document, the 1215 Magna Carta of England, is also credited with limiting the powers of the monarchy and is sometimes cited as a precursor to the English Bill of Rights.

John Locke

Many historians also believe that the ideas of English philosopher John Locke greatly influenced the content of the Bill of Rights. Locke proposed that the role of the government is to protect its citizens’ natural rights.

The Bill of Rights was quickly followed by the 1689 Mutiny Act, which limited the maintenance of a standing army during peacetime to one year.

In 1701, the English Bill of Rights was supplemented by England’s Act of Settlement, which was essentially designed to further ensure Protestant succession to the throne.

U.S. Bill of Rights

The English Bill of Rights encouraged a form of government where the rights and liberties of individuals were protected. These ideas and philosophies penetrated into the colonies of North America.

Many of the themes and philosophies found in the English Bill of Rights served as inspirations for principles that were eventually included in the American Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, the U.S. Constitution and, of course, the U.S. Bill of Rights.

For example, the 1791 U.S. Bill of Rights guarantees freedom of speech, trial by jury and protection from cruel and unusual punishment.

Legacy of the English Bill of Rights

The English Bill of Rights has had a long-lasting impact on the role of government in England. It’s also influenced laws, documents and ideologies in the United States, Canada, Australia, Ireland, New Zealand and other countries.

The act limited the power of the monarchy, but it also bolstered the rights and liberties of individual citizens. Without the English Bill of Rights, the role of the monarchy might be much different than it is today.

There’s no question that this one act greatly affected how the English government operates and served as a stepping stone for modern-day democracies.

Источники информации:

- http://saylordotorg.github.io/text_american-government-and-politics-in-the-information-age/s08-01-the-bill-of-rights.html

- http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/United_States_Bill_of_Rights

- http://www.revolutionary-war-and-beyond.com/bill-of-rights.html

- http://www.history.com/topics/british-history/english-bill-of-rights