What happened in 1812

What happened in 1812

War of 1812

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

The commercial restrictions that Britain’s war with France imposed on the U.S. exacerbated the U.S.’s relations with both powers. Although neither Britain nor France initially accepted the U.S.’s neutral rights to trade with the other—and punished U.S. ships for trying to do so—France had begun to temper its intransigence on the issue by 1810. That, paired with the ascendance of certain pro-French politicians in the U.S. and the conviction held by some Americans that the British were stirring up unrest among Native Americans on the frontier, set the stage for a U.S.-British war. The U.S. Congress declared war in 1812.

Peace talks between Britain and the U.S. began in 1814. Britain stalled negotiations as it waited for word of a victory in America, having recently committed extra troops to its western campaign. But news of their losses at places like Plattsburgh, New York, and Baltimore, Maryland, paired with the duke of Wellington’s counsel against continuing the war, convinced the British to pursue peace more genuinely, and both sides signed the Treaty of Ghent in December 1814. The final battle of the war occurred after this, when a British general unaware of the peace treaty led an assault on New Orleans that was roundly crushed.

The War of 1812 had only mixed support on both sides of the Atlantic. The British weren’t eager for another conflict, having fought Napoleon for the better part of the previous 20 years, but weren’t fond of American commercial support of the French either. The divisions in American sentiment about the war similarly split, oftentimes along geographic lines: New Englanders, particularly seafaring ones, were against it. Southerners and Westerners advocated for it, hoping that it would enhance the U.S.’s reputation abroad, open opportunities for its expansion, and protect American commercial interests against British restrictions.

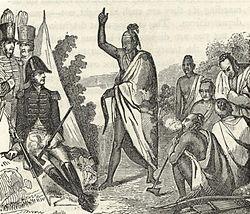

Native Americans had begun resisting settlement by white Americans before 1812. In 1808 the Shawnee brothers Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa began amassing an intertribal confederacy comprising indigenous groups around the Great Lakes and the Ohio River valley. In 1812 Tecumseh tightened his relationship with Britain, convincing white Americans that the British were inciting unrest among northwestern tribes. British and intertribal forces took Detroit in 1812 and won a number of other victories during the war, but Tecumseh was killed and his confederation was quashed after Detroit was retaken in 1813. Creek tribes continued to resist from 1813 onward, but they were suppressed by Andrew Jackson’s forces in 1814.

Although neither Britain nor the U.S. was able to secure major concessions through the Treaty of Ghent, it nevertheless had important consequences for the future of North America. The withdrawal of British troops from the Northwest Territory and the defeat of the Creeks in the South opened the door for unbounded U.S. expansionism in both regions. The treaty also established measures that would help arbitrate future border disputes between the U.S. and Canada, perhaps one reason why the two countries have been able to peaceably share the longest unfortified border in the world ever since.

Read a brief summary of this topic

War of 1812, (June 18, 1812–February 17, 1815), conflict fought between the United States and Great Britain over British violations of U.S. maritime rights. It ended with the exchange of ratifications of the Treaty of Ghent.

Major causes of the war

The tensions that caused the War of 1812 arose from the French revolutionary (1792–99) and Napoleonic Wars (1799–1815). During this nearly constant conflict between France and Britain, American interests were injured by each of the two countries’ endeavours to block the United States from trading with the other.

American shipping initially prospered from trade with the French and Spanish empires, although the British countered the U.S. claim that “free ships make free goods” with the belated enforcement of the so-called Rule of 1756 (trade not permitted in peacetime would not be allowed in wartime). The Royal Navy did enforce the act from 1793 to 1794, especially in the Caribbean Sea, before the signing of the Jay Treaty (November 19, 1794). Under the primary terms of the treaty, American maritime commerce was given trading privileges in England and the British East Indies, Britain agreed to evacuate forts still held in the Northwest Territory by June 1, 1796, and the Mississippi River was declared freely open to both countries. Although the treaty was ratified by both countries, it was highly unpopular in the United States and was one of the rallying points used by the pro-French Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, in wresting power from the pro-British Federalists, led by George Washington and John Adams.

After Jefferson became president in 1801, relations with Britain slowly deteriorated, and systematic enforcement of the Rule of 1756 resumed after 1805. Compounding this troubling development, the decisive British naval victory at the Battle of Trafalgar (October 21, 1805) and efforts by the British to blockade French ports prompted the French emperor, Napoleon, to cut off Britain from European and American trade. The Berlin Decree (November 21, 1806) established Napoleon’s Continental System, which impinged on U.S. neutral rights by designating ships that visited British ports as enemy vessels. The British responded with Orders in Council (November 11, 1807) that required neutral ships to obtain licenses at English ports before trading with France or French colonies. In turn, France announced the Milan Decree (December 17, 1807), which strengthened the Berlin Decree by authorizing the capture of any neutral vessel that had submitted to search by the British. Consequently, American ships that obeyed Britain faced capture by the French in European ports, and if they complied with Napoleon’s Continental System, they could fall prey to the Royal Navy.

The Royal Navy’s use of impressment to keep its ships fully crewed also provoked Americans. The British accosted American merchant ships to seize alleged Royal Navy deserters, carrying off thousands of U.S. citizens into the British navy. In 1807 the frigate H.M.S. Leopard fired on the U.S. Navy frigate Chesapeake and seized four sailors, three of them U.S. citizens. London eventually apologized for this incident, but it came close to causing war at the time. Jefferson, however, chose to exert economic pressure against Britain and France by pushing Congress in December 1807 to pass the Embargo Act, which forbade all export shipping from U.S. ports and most imports from Britain.

The Embargo Act hurt Americans more than the British or French, however, causing many Americans to defy it. Just before Jefferson left office in 1809, Congress replaced the Embargo Act with the Non-Intercourse Act, which exclusively forbade trade with Great Britain and France. This measure also proved ineffective, and it was replaced by Macon’s Bill No. 2 (May 1, 1810) that resumed trade with all nations but stipulated that if either Britain or France dropped commercial restrictions, the United States would revive nonintercourse against the other. In August, Napoleon insinuated that he would exempt American shipping from the Berlin and Milan decrees. Although the British demonstrated that French restrictions continued, U.S. Pres. James Madison reinstated nonintercourse against Britain in November 1810, thereby moving one step closer to war.

Britain’s refusal to yield on neutral rights derived from more than the emergency of the European war. British manufacturing and shipping interests demanded that the Royal Navy promote and sustain British trade against Yankee competitors. The policy born of that attitude convinced many Americans that they were being consigned to a de facto colonial status. Britons, on the other hand, denounced American actions that effectively made the United States a participant in Napoleon’s Continental System.

What actually caused the Russo-French War of 1812?

Russia Beyond (Photo: Library of Congress, Public domain)

In this article, we do not go into the military details of Napoleon’s 1812 campaign against Russia – you can read them here. Rather, this article is aimed at explaining the political and economical reasons behind the biggest military conflict of the 19th century.

Napoleon’s 1812 ‘Russian Campaign’

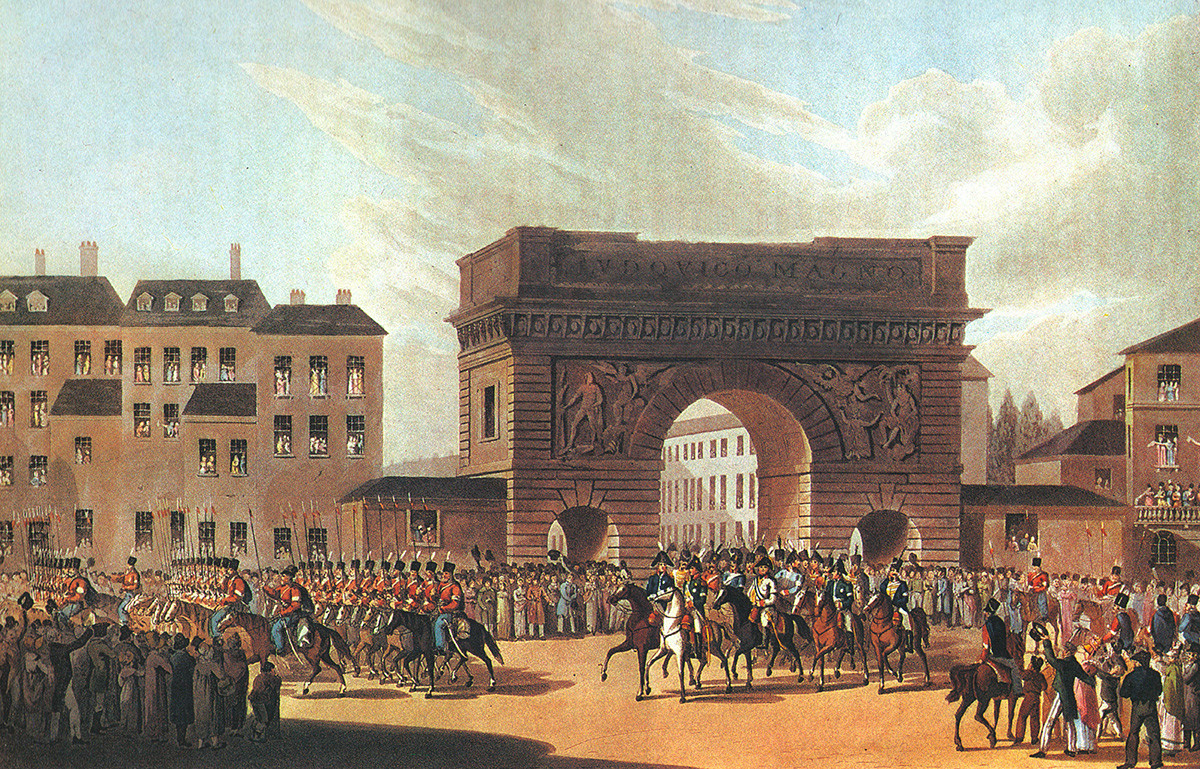

Entry of Napoleon I into Berlin, 27th October 1806, by Charles Meynier

Palace of Versailles

The main reason why the 1812 war between Napoleon’s France and Russia began was sanctions – the so-called Napoleon’s ‘Continental System’. But what was it?

In 1792-1793, the Republic of France was involved in the French Revolutionary Wars – France fought against Great Britain, Austria, Prussia, Russia and several other monarchies. The “old” monarchies of Europe detested the republican system of government installed in France. Meanwhile, Napoleon Bonaparte emerged in France, a young genius war commander, who, by 1799, had become de facto leader of France.

By the beginning of the 1800s, France had conquered territories on the Italian Peninsula, the Netherlands and the Rhineland. Great Britain remained France’s only opponent in Europe. After the Battle of Trafalgar of 1805, it became obvious that the French navy was useless against the British fleet, so Napoleon began strengthening the Continental System – a large-scale embargo against British trade on the European continent.

Napoleon wanted to destroy Britain’s ability to trade, to drain it financially. The Berlin Decree of 1806 proclaimed that “the British Isles are declared to be in a state of blockade” and forbade all correspondence or commerce with Great Britain. However, European countries constantly breached the blockade, which caused attacks on them by Napoleonic France. The Russian Empire, Great Britain’s main European economic partner at the time, was also France’s main enemy and the main obstacle in successfully implementing the Continental System.

Russia and the Continental System

Meeting between Napoleon Bonaparte and Czar Alexander I Romanov at Tilsit, June 25, 1807.

DEA/M. SEEMULLER/Getty Images

In the Battle of Friedland (1807), Napoleon defeated, if not crushed, the Russian army. After that, Alexander I of Russia agreed to sign the Treaty of Tilsit, which had Russia and Prussia ally with France against Great Britain and Sweden.

The Treaty of Tilsit enraged the Russian public – making peace with a republican whose army put thousands of Russian soldiers to death! However, by 1810, Russia resumed trade with England through other countries, while French goods were taxed heavily. Meanwhile, Napoleon tried to strengthen his ties with Alexander I by offering his hand to Alexander’s sisters, but was refused twice.

By 1811, Napoleon was openly speaking about his hostile attitude towards Russia. He said to Dominique Dufour de Pradt, the French ambassador in Warsaw: “In five years, I shall be the master of the world, Russia alone remains; but I shall crush her. I shall then also be the master of the seas and all commerce must, of course, pass through my hands.” It had been obvious the war was near.

What was this war for Russia

«Mikhail Kutuzov as the head of the St. Petersburg militia,» by S. Gerasimov

Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation

As researcher Mikhail Belizhev notes, “The scale of the war itself was unique. For the first time since the 17th century, war was waged on the territory of the Russian Empire, which was a real shock for contemporaries. Moscow, the heart of the empire, was given to the French and largely destroyed – at that time, it was interpreted as a national catastrophe. The country suffered enormous losses: up to a million residents of Russia perished in 1812-1814; material damage was estimated at several billion rubles.”

«The arrival of Mikhail Kutuzov in Tsarevo-Zaymishche» («Kutuzov takes the command over the Russian Imperial Army»), by Sergey Gerasimov

Panorama Museum «Battle of Borodino»

The Great Army decisively entered Russia and, enduring constant resistance from the Russian army, moved towards Smolensk, the fortress considered the “key to Moscow” and took it in August 1812. However, the onslaught wasn’t easy, as both the Russian army and civilian population implemented a scorched-earth policy: when retreating, the Russian soldiers destroyed food storages, ammo supplies and any assets that could be used by the enemy. Who implemented this policy?

The Scottish man behind the Russian victory

Mikhail B. Barclay de Tolly (1761-1818). Russian Fieldmarshal and Minister of War. Portrait by George Dawe (1781-1829), 1829. The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia.

PHAS/Universal Images/Getty Images

Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly (1761-1818) was a Baltic German officer of Scottish origin in the Russian service. A descendant of the Scottish Clan Barclay, he grew up in St. Petersburg and entered the military service in 1776. He would later become field marshal of the Russian Empire.

Barclay was War Minister in 1810-1812. He effectively prepared the Russian army for the decisive fight with Napoleon, ordering and personally creating a great lot of tactical and strategic tutorials and manuals for the soldiers and officers. When the war began, Barclay and General Pyotr Bagration were both functioning as commanders-in-chief of the Russian army.

«The Military Council in Fili» (1880) by Sergey Kivshenko

However, it was Barclay who initially devised the masterplan for the Russian army during this war: using a scorched-earth policy, retreat back into Central Russia to drain the resources of the French army. The French supply routes, Barclay rightfully reckoned, would become too long to supply the army from Europe and the Russian partisans and the army would do the rest to crush the enemy.

At the Council at Fili, which happened shortly after the Battle of Borodino, Barclay firmly voted for leaving Moscow to Napoleon, a wise strategic move that eventually captured the French Emperor in cold, brazen and burning Moscow, devoid of supplies. Trusting the command of the army to Mikhail Kutuzov, Barclay nevertheless stayed in command of one of the armies and fought later in Russia’s European campaign of 1812-1814.

«The entry of Russian troops into Paris. March 31, 1814»: an unknown artist from the original by I. F. Yugel based on a drawing by U.L. Wolf, 1815.

Russian historians of the 1812 campaign are unanimous in the opinion that Barclay’s initial strategy wasn’t changed by Mikhail Kutuzov as he took command of the army. After the victory over Napoleon, Barclay was showered with awards and recognitions. He was elevated to princely dignity by Emperor Alexander I and widely considered to be the main mind behind Russia’s victory over Napoleon.

Meanwhile, Napoleon’s Continental System, that served as the main reason for Napoleon’s onslaught on Russia, was ended by Russia as early as September 1812, when Alexander I published a manifesto on the resumption of trade relations between Russia and Great Britain.

If using any of Russia Beyond’s content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

War of 1812

DEA Picture Library/Getty Images

Contents

In the War of 1812, the United States took on the greatest naval power in the world, Great Britain, in a conflict that would have an immense impact on the young country’s future. Causes of the war included British attempts to restrict U.S. trade, the Royal Navy’s impressment of American seamen and America’s desire to expand its territory.

The United States suffered many costly defeats at the hands of British, Canadian and Native American troops over the course of the War of 1812, including the capture and burning of the nation’s capital, Washington, D.C., in August 1814. Nonetheless, American troops were able to repulse British invasions in New York, Baltimore and New Orleans, boosting national confidence and fostering a new spirit of patriotism. The ratification of the Treaty of Ghent on February 17, 1815, ended the war but left many of the most contentious questions unresolved. Nonetheless, many in the United States celebrated the War of 1812 as a “second war of independence,” beginning an era of partisan agreement and national pride.

Causes of the War of 1812

At the outset of the 19th century, Great Britain was locked in a long and bitter conflict with Napoleon Bonaparte’s France. In an attempt to cut off supplies from reaching the enemy, both sides attempted to block the United States from trading with the other. In 1807, Britain passed the Orders in Council, which required neutral countries to obtain a license from its authorities before trading with France or French colonies. The Royal Navy also outraged Americans by its practice of impressment, or removing seamen from U.S. merchant vessels and forcing them to serve on behalf of the British.

In 1809, the U.S. Congress repealed Thomas Jefferson’s unpopular Embargo Act, which by restricting trade had hurt Americans more than either Britain or France. Its replacement, the Non-Intercourse Act, specifically prohibited trade with Britain and France. It also proved ineffective, and in turn was replaced with a May 1810 bill stating that if either power dropped trade restrictions against the United States, Congress would in turn resume non-intercourse with the opposing power.

After Napoleon hinted he would stop restrictions, President James Madison blocked all trade with Britain that November. Meanwhile, new members of Congress elected that year—led by Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun—had begun to agitate for war, based on their indignation over British violations of maritime rights as well as Britain’s encouragement of Native American hostility against American westward expansion.

Did you know? The War of 1812 produced a new generation of great American generals, including Andrew Jackson, Jacob Brown and Winfield Scott, and helped propel no fewer than four men to the presidency: Jackson, John Quincy Adams, James Monroe and William Henry Harrison.

The War of 1812 Breaks Out

In the fall of 1811, Indiana’s territorial governor William Henry Harrison led U.S. troops to victory in the Battle of Tippecanoe. The defeat convinced many Indians in the Northwest Territory (including the celebrated Shawnee chief Tecumseh) that they needed British support to prevent American settlers from pushing them further out of their lands.

Meanwhile, by late 1811 the so-called “War Hawks” in Congress were putting more and more pressure on Madison, and on June 18, 1812, the president signed a declaration of war against Britain. Though Congress ultimately voted for war, both House and Senate were bitterly divided on the issue. Most Western and Southern congressmen supported war, while Federalists (especially New Englanders who relied heavily on trade with Britain) accused war advocates of using the excuse of maritime rights to promote their expansionist agenda.

Recommended for you

8 Fascinating Facts About Ancient Roman Medicine

What Caused Ancient Egypt’s Decline?

The 6 Earliest Human Civilizations

In order to strike at Great Britain, U.S. forces almost immediately attacked Canada, which was then a British colony. American officials were overly optimistic about the invasion’s success, especially given how underprepared U.S. troops were at the time. On the other side, they faced a well-managed defense coordinated by Sir Isaac Brock, the British soldier and administrator in charge in Upper Canada (modern Ontario).

On August 16, 1812, the United States suffered a humiliating defeat after Brock and Tecumseh’s forces chased those led by Michigan William Hull across the Canadian border, scaring Hull into surrendering Detroit without any shots fired.

War of 1812: Mixed Results for American Forces

Things looked better for the United States in the West, as Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry’s brilliant success in the Battle of Lake Erie in September 1813 placed the Northwest Territory firmly under American control. Harrison was subsequently able to retake Detroit with a victory in the Battle of Thames (in which Tecumseh was killed). Meanwhile, the U.S. navy had been able to score several victories over the Royal Navy in the early months of the war. With the defeat of Napoleon’s armies in April 1814, however, Britain was able to turn its full attention to the war effort in North America.

As large numbers of troops arrived, British forces raided the Chesapeake Bay and moved in on the U.S. capital, capturing Washington, D.C., on August 24, 1814, and burning government buildings including the Capitol and the White House.

On September 11, 1814, at the Battle of Plattsburgh on Lake Champlain in New York, the American navy soundly defeated the British fleet. And on September 13, 1814, Baltimore’s Fort McHenry withstood 25 hours of bombardment by the British Navy.

The following morning, the fort’s soldiers hoisted an enormous American flag, a sight that inspired Francis Scott Key to write a poem that would later be set to music and become known as “The Star-Spangled Banner.” (Set to the tune of an old English drinking song, it would later be adopted as the U.S. national anthem.) British forces subsequently left the Chesapeake Bay and began gathering their efforts for a campaign against New Orleans.

End of the War of 1812 and Its Impact

By that time, peace talks had already begun at Ghent (modern Belgium), and Britain moved for an armistice after the failure of the assault on Baltimore. In the negotiations that followed, the United States gave up its demands to end impressment, while Britain promised to leave Canada’s borders unchanged and abandon efforts to create an Indian state in the Northwest. On December 24, 1814, commissioners signed the Treaty of Ghent, which would be ratified the following February.

On January 8, 1815, unaware that peace had been concluded, British forces mounted a major attack in the Battle of New Orleans, only to meet with defeat at the hands of future U.S. president Andrew Jackson’s army. News of the battle boosted sagging U.S. morale and left Americans with the taste of victory, despite the fact that the country had achieved none of its pre-war objectives.

Impact of the War of 1812

Though the War of 1812 is remembered as a relatively minor conflict in the United States and Britain, it looms large for Canadians and for Native Americans, who see it as a decisive turning point in their losing struggle to govern themselves. In fact, the war had a far-reaching impact in the United States, as the Treaty of Ghent ended decades of bitter partisan infighting in government and ushered in the so-called “Era of Good Feelings.”

The war also marked the demise of the Federalist Party, which had been accused of being unpatriotic for its antiwar stance, and reinforced a tradition of Anglophobia that had begun during the Revolutionary War. Perhaps most importantly, the war’s outcome boosted national self-confidence and encouraged the growing spirit of American expansionism that would shape the better part of the 19th century.

What Happened in 1812

Beethoven Composes His Eighth Symphony

Symphony No. 8 in F Major, Op. 93 is a symphony in four movements composed by Ludwig van Beethoven in 1812. Beethoven fondly referred to it as «my. Read more

The Davis Family Settles in Wilkinson County in southwestern Mississippi

During Davis’ youth, the family moved twice; in 1811 to St. Mary Parish, Louisiana, and in 1812 to Wilkinson County, Mississippi near the town of. Read more

Charles Dickens is born

Charles Dickens was born on February 7, 1812 in Portsmouth. His parents were John and Elizabeth Dickens. Charles was the second of their eight. Read more

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin Is Born

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1 March 1812 – 14 September 1852) was an English architect, designer, and theorist of design, now best remembered. Read more

Caracas Earthquake of 1812

The 1812 Caracas earthquake took place in Venezuela on March 26, 1812 (on Maundy Thursday) at 4:37 p.m. It measured 7.7 on the Richter magnitude. Read more

Louisiana is the 18th State Admitted to the Union

The Territory of Orleans was established by the Act of March 26, 1804 and was effective October 1, 1804. It remained a Territory until. Read more

Felling Mine Disaster

On the 25th of May, 1812, an explosion occurred at Brandling Main, of Felling Colliery, near Gateshead-on-Tyne, which was attended with a more. Read more

War of 1812

The War of 1812, between the United States of America and the British Empire (particularly Great Britain and British North America), was fought. Read more

Beethoven Writes His Letter To the «Immortal Beloved»

It is likely that Beethoven was at Teplitz when he wrote three love letters to an «Immortal Beloved». While the identity of the intended recipient. Read more

Fort Dearborn Massacre

The Fort Dearborn massacre occurred on August 15, 1812, near Fort Dearborn, Illinois Territory (in what is now Chicago, Illinois) during the War of. Read more

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was a military conflict between the United States and the United Kingdom which lasted from 1812 to 1815, hence the name. Depending on who’s looking at it, the conflict was either a backwater sideshow of the Napoleonic Wars or a full war in its own right. Although the war had some roots in the dispute over Britain’s impressment of American sailors for the blockade of France, the most significant cause of war was the UK’s supply of arms to the various Native American tribes who were fighting against the United States. The war was also responsible for some dramatic episodes in American history like the burning of Washington DC and the penning of the Star Spangled Banner.

The impressment of sailors issue became moot after Napoleon’s abdication in 1814, and both sides signed the Treaty of Ghent later that year. There were no boundary changes. However, while the war may have been a draw on paper, in reality it was a major victory for the United States. This is because America’s victories over the Indians during the war and the UK’s changing priorities led London to completely abandon their indigenous allies, leaving them to the US’s (lack of) mercy. [3]

Contents

Origins [ edit ]

Trade and naval disputes [ edit ]

The ascension of the pro-French Thomas Jefferson to the presidency in 1801 caused trade and diplomatic relations between the United States and Great Britain to deteriorate. [4] Meanwhile, the Royal Navy began waylaying American ships to haul away individuals who (they alleged) were British deserters. [5] The Royal Navy operated «press gangs», which were legally empowered to conscript any British citizen into naval service, even if they happened to be found on a foreign ship. [6] Britain’s need for manpower on warships was greatly exacerbated by frequent desertions, which frankly should have been unsurprising considering the British method of naval recruitment. [6] Deserters often fled to the United States to serve on American ships; this combined with the near-identical cultures of the two nations led to frequent instances where British commanders would wrongfully impress American citizens into service on British ships. [7] This, of course, led to popular outrage among the American populace, who viewed this as a deliberate attempt by the British to attack the new American nation.

Impressment is traditionally considered to be the primary cause of the war although it probably wasn’t. After all, Britain’s wars with France had been going on for decades. Yet Great Britain’s maritime policies never resulted in war until the U.S. 1810 elections swept the so-called «War Hawks» into Congress. This group comprised Southerners and Westerners who longed to gain more land to exploit for agriculture, leading them to agitate first for war with Britain with a view to seizing the upper Midwest and possibly Canada. [8] Maritime disputes served as a useful pretext.

Indian wars [ edit ]

Anti-British fervor was thus most intense on the frontiers, with people from the region convinced that their problems would end once the British were expelled.

American expansion [ edit ]

Although it’s debatable how significant American expansionism was as a cause for war, a significant segment of the American population was toying with the idea of annexing Canada and expelling the British from North America entirely. [13] Annexation was an especially popular prospect among northern frontier businessmen who wanted to fully control trade routes in the Great Lakes. [14] And, of course, removing British Canada would also remove British support for Native Americans, making them easier prey for American frontiersmen. Overconfident American politicians, most notably Thomas Jefferson, believed that the conquest of Canada would be «a mere matter of marching». [15] This, of course, was completely absurd given Canada’s rugged terrain and the UK’s powerful military.

Meanwhile, slaveholding southerners also had designs on Spanish-held Florida and were already expanding the institution across the southern portion of the Louisiana Purchase. It was noted at the time that the imbalance between Southern slave states and Northern free states could most easily be set right if Canada were made part of the Union. [16] Southerners also hoped that annexing Spanish Florida would allow them to finally destroy the raiding tribes of Creek and Seminole Indians. [17]

Woefully incomplete summary of the war [ edit ]

The American declaration of war barely scraped through the legislature by a margin of 79–49 in the House and 19-13 in the Senate. [5] The Federalist Party, mostly made up of New England merchant traders, accused the War Hawks of disguising base expansionism with claims of maritime abuses. This, as we see above, was entirely correct.

The United States military was small and poorly-trained, and the opening invasion of Canada was an embarrassing disaster in which American forces advanced about a dozen miles into Quebec before being forced back and finally surrendering Detroit. [18] An attempt to retake Detroit ended with a total loss, although the subsequent slaughter of American soldiers by Native Americans created a rallying cry among Americans for the remainder of the war. [19]

After another abortive American attempt to invade Canada in 1814, the (temporary) end of hostilities in Europe allowed the British to shift their attention to North America. The war carried on despite the fact that the British were repealing their trade and maritime policies, essentially rendering the casus belli moot. [18] The British landed troops in Maryland, smashed the Americans in battle despite being outnumbered, and marched into Washington DC, burning most of America’s government buildings. [22] After this, the British turned north to Baltimore, hoping to destroy the vital port city and thus force peace. However, the city was defended by the formidable Fort McHenry, which survived a 25-hour British attack and forced them to abandon their plans of taking Baltimore. [23] This victory inspired local lawyer Francis Scott Key to write the poem which would become the US national anthem. [24] So you’d better show respect and stand for the anthem!

After this, both sides came together to sign the Treaty of Ghent, ending the war. However, word didn’t quite get around quickly enough. Andrew Jackson defended New Orleans from a British invasion in a brilliant but pointless battle that would earn him national fame and set him on the path to the White House. [25] For more information on how that would impact the Native Americans, see our article on the Amerindian genocides.

Peace, but not for the Indians [ edit ]

During the negotiations, the British demanded that the Americans respect the territory of their Native allies in the upper Midwest. [2] However, when push came to shove, the British agreed to abandon the Indians in exchange for American pinky-swears not to attack Canada. Although no losses of land were formalized by the treaty, it was still a disaster for the Native Americans. Without material aid from the British, Native Americans were unable to truly pose a threat to the United States. Indian wars, which had previously been full-scale struggles like the Creek wars or the Northwest Indian War, instead became little more than cleanup operations.

This stunning loss of power for the Natives also had another impact: on the American psyche. Rather than a conflict partner which must be taken seriously, Indians became barbarians and nuisances in the eyes of Americans. It was their powerlessness that allowed Americans to view them as inferior. Thus cognitive dissonance set in. In 1845, William Gilmore Simms wrote, [27]

By 1871, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs declared, [28]

A century of war and extermination would follow.