What is capital of spain

What is capital of spain

Madrid

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

Madrid is in central Spain. The city proper and province form a comunidad autónoma (autonomous community) within Spain.

Madrid was officially made the capital of Spain in 1561 by Philip III, a generation after Philip II relocated the royal court to the city.

On March 11, 2004, Madrid suffered a series of terrorist attack. Ten bombs, detonated by Islamist militants, exploded on four trains at three different rail stations during rush hour. The attacks killed 191 people and injured some 1,800 others.

Read a brief summary of this topic

Madrid, city, capital of Spain and of Madrid provincia (province). Spain’s arts and financial centre, the city proper and province form a comunidad autónoma (autonomous community) in central Spain.

Madrid’s status as the national capital reflects the centralizing policy of the 16th-century Spanish king Philip II and his successors. The choice of Madrid, however, was also the result of the city’s previous obscurity and neutrality: it was chosen because it lacked ties with an established nonroyal power rather than because of any strategic, geographic, or economic considerations. Indeed, Madrid is deficient in other characteristics that might qualify it for a leading role. It does not lie on a major river, as so many European cities do; the 16th–17th-century dramatist Lope de Vega, referring to a magnificent bridge over the distinctly unimposing waters of the Manzanares, suggested either selling the bridge or buying another river. Madrid does not possess mineral deposits or other natural wealth, nor was it ever a destination of pilgrimages, although its patron saint, San Isidro, enjoys the all-but-unique distinction of having been married to another saint. Even the city’s origins seem inappropriate for a national capital: its earliest historical role was as the site of a small Moorish fortress on a rocky outcrop—part of the northern defenses of what was then the far more important city of Toledo, located about 43 miles (70 km) south-southwest.

Madrid was officially made the national capital by Philip III, an entire generation after Philip II took the court to Madrid in 1561. Under the patronage of Philip II and his successors, Madrid developed into a city of curious contrasts, preserving its old, overcrowded centre, around which developed palaces, convents, churches, and public buildings. Pop. (2011) 3,198,645; (2018 est.) 3,223,334.

Physical and human geography

The landscape

The city site and climate

Madrid lies almost exactly at the geographical heart of the Iberian Peninsula. It is situated on an undulating plateau of sand and clay known as the Meseta (derived from the Spanish word mesa, “table”) at an elevation of some 2,120 feet (646 metres) above sea level, making it one of the highest capitals in Europe. This location, together with the proximity of the Sierra de Guadarrama, is partly responsible for the weather pattern of cold, crisp winters accompanied by sharp winds. Sudden variations of temperature are possible, but summers are consistently dry and hot, becoming especially oppressive in July and August, when temperatures sometimes rise above 100 °F (38 °C). Average temperatures range between 41 and 75 °F (5 and 24 °C), while average precipitation varies between a low of less than 0.5 inch (11 mm) in July up to about 2 inches (50 mm) in October, usually the rainiest month of the year. The temperate times of year are spring and fall, which are also the most attractive seasons for visitors.

What is the Capital of Spain?

Madrid is the capital of Spain and the administrative center of the Madrid region. It is located in the central part of the Iberian Peninsula.

Madrid is the largest city in Spain and the fifth most populous city in Europe after Istanbul, London, Berlin, and Paris.

According to the excavation, the human traces of the region and the history of Madrid extend back to the paleolithic time. There are trivial small settlements here that belong to the Roman settlement of the 2nd century BC and the next Visigoths.

According to recent researches and a theory, the name of Madrid originates from the name Matrice given to this region by these early settlements.

When did Madrid Become the Capital?

For the first time, Henry III of Castile built a palace in the El Pardo district outside Madrid today, early in the 1400’s.

In 1561, Philip II of Spain moved the Royal Courts to Madrid, a small and insignificant settlement, and shortly after, Madrid was declared the capital. Thus Madrid’s population has reached 30,000. Soon new palaces, churches, monasteries, and roads were built in Madrid. A lot of noble, wealthy and statesmen settled in Madrid with the attraction of the new capital.

With the discovery of the New World in the Middle Ages and the gold and wealth from South America, Madrid has grown and enriched. In the 18th Century, during the reign of Charles II of Spain, Madrid was renewed and the landscape had a European appearance. For this reason, Charles II of Spain has the appellation of “Madrid’s Best Mayor”.

The history of Madrid has recently been quite turbulent and gray. The end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century are the most severe periods of economic crisis in Spain. This crisis triggered the political turmoil of the country and eventually led to the Spanish Civil War.

Between 1936 and 1939, according to some sources, over 600,000 people lost their lives in the Spanish Civil War, one of the world’s greatest civil wars between the fascist General Franco from the radical right and the Republican left. The result was Franco’s victory and the 40-year dictatorship started.

Franco proclaimed all the state institutions in Madrid and gave Madrid some privileges according to other cities.

With the death of Franco in 1978, the dictatorship ended in Spain, the Juan Carlos I of Spain came back to the country, and the time of new democratic constitution and today’s parliamentary democratic Spain has begun.

Features of Madrid

In addition to its rich historical heritage, it is also a vital cultural and artistic center. It is in recent history that it has gained a dominant role in the development and in the economy of the country. The area of the metropolitan area is 1,020 km² and its population is over 4 million.

Madrid, one of the highest capitals of Europe, is at an altitude of 635 m on a wavy plateau of the Central Plateau. Sudden temperature changes are common because of their high position and the influence of air masses. The summer months are suffocating and the temperature sometimes reaches 38 ° C. The average annual temperature varies between 2 ° and 24 ° C.

Contributors to the banking and insurance-based economy are administrative services, transport network, and tourism income. After World War II, industry developed and manufacturing sector increased.

Major industrial goods include railway and tractor construction, conversion metallurgy, construction of electrical appliances. Moreover, food industry, textile, chemical, plastics processing, optical goods, automobile, and truck engines are important.

Important Places to See in Madrid

Madrid, is a city of history, thanks to the Muslims who went to Toledo in the 12th century. The city lags behind Barcelona in tourist terms. However, Neo-Classical buildings, 24 hours alive streets, popular restaurants, and lively nightlife are quite attractive to tourists. At the beginning of the places to see in Madrid; Prado Museum, Plaza Mayor and Royal Palace of Madrid.

What Is The Capital Of Spain?

One of the main shopping streets in Madrid, the capital of Spain.

Madrid is the third-largest city in the European Union behind only London and Berlin. It is the capital and largest city of Spain with a population of roughly 3.2 million. The entire metropolitan area of Madrid accounts for an estimated 6.5 million inhabitants. The city’s metropolitan area is also the third largest in the European Union after that of London and Paris. Madrid’s municipality covers an area of approximately 233.3 square miles.

Overview Of The Capital City Of Spain

Madrid is a business center, a cosmopolitan city, headquarters for the Spanish government, public administration, parliament and also home to the Royal Spanish family. The city also plays a significant role in the industrial and banking sectors. A large number of industries found in Madrid are situated in the southern region of the city where major food, textile, and metalworking factories can be found clustered together. Madrid has a major influence on fashion, politics, culture, entertainment, science, arts, media, environment, and education. The city is home to two famous football clubs: Atletico Madrid and Real Madrid. Madrid is also best known for its intense cultural and artistic activities coupled with a robust nightlife

The History Of Madrid

The grand metropolis of Madrid traces its roots back to the 9th century during the times of Muhammad I, the 5 th Emir of Cordoba. Muhammad I ordered the construction of a fortress on the left bank of the Manzanares River. Later on, the region became a subject of conflict between the Arabs and the Christians. The region was eventually conquered by Alonso VI of León and Castile in 1085, with Christians dominating the city and integrating it as the Crown’s property into the Kingdom of Castile. The city center was occupied by Christians while Jews and Muslims relocated to the suburbs. The region’s administrative district stretched to the Guadarrama River in the west from the Jarama River in the east and since it was prospering it was known as Villa.

The Economy Of Madrid

Madrid is the largest financial center in Spain and among the largest in Europe with the city`s biggest employers being Drafados, Telefónica, BBVA, Urbaser, Iberia, FCC, and Prosegur. Madrid is home to more than 30 research centers and 17 universities. It also ranks 4 th in the EU by gross internal product. The service sector contributes significantly to the economy of the city accounting for 85.9% of the total economy. Other contributing sectors to the economy included construction which accounted for 6.1% and industry, which accounted for 7.9% in 2011.

Attractions In Madrid

Madrid is a city full of energy and one that offers a wide array of cultural attractions providing a real taste of the country of Spain. Madrid is never short of tourists as Spain is among the most visited countries in Europe. The city is home to several monuments and art museums including other attractions. Some of the attractions in Madrid include the Prado Museum, the Royal Palace, Puerta del Sol, Archeology Museum, Plaza Mayor, the Buen Retiro Park, the Royal Chapel of St. Anthony of La Florida, among many others.

Nightlife In Madrid

One of the main attractions in the city of Madrid is its nightlife. The city is home to numerous jazz lounges, flamenco theaters, tapas bars, clubs, live music venues, cocktail bars and all sorts of entertainment establishments. La Noche en Vivo, the Live Music Venues Association, is responsible for hosting a broad range of live music shows. The city’s nightlife together with its young cultural awakening that mostly prospered during the 80s following the demise of Franco. Tribunal, Huertas, Alonso Martinez, Atocha, Bilbao and the Puerta del Sol area are among the most famous neighborhoods for nightlife in the city.

What is capital of spain

The city is located on the Manzanares river in the centre of both the country and the Community of Madrid (which comprises the city of Madrid, its conurbation and extended suburbs and villages); this community is bordered by the autonomous communities of Castile and León and Castile-La Mancha.

There are many places of interest. Such as:

Royal Palace of El Pardo. A little village in the municipality of Madrid (8 km. from the city center) and close of «Palacio de la Zarzuela» (residence of the King of Spain), surrounded by mountains and the location of the «Palacio de El Pardo» (El Pardo Palace), Franco′s residence between 1940 until his death (1975). It was a former residence of the Kings of Spain.

Templo de Debod. An Egyptian temple, located in one of Madrid′s most beautiful parks. Near the Royal Palace and Plaza de España, it was a present given by Egypt to Spain for its role in saving the temple of Abu Simbel from the floodwaters of Lake Nasser following the construction of the Aswan Dam in southern Egypt. A great place to watch the sunset.

El Retiro Park. The main park of Madrid, the perfect place to take a rest during a sunny day, or take part in the drum circles around the statue of Alphonso XII on summer evenings. There is a large boating lake where one can hire a rowing boat. There is a monument to the victims of the Madrid 3/11 terrorist bombings, the Forest of the Absent, and the Crystal Palace, a large structure entirely made of glass.

Puerta del Sol. This plaza is the «heart» of Madrid and one of the busiest places in the city, and a favourite meeting spot for locals. On the north side of the plaza there is a famous statue of an oso (bear) climbing the madroño tree, which is the symbol of Madrid. Also in Sol, just in front of the Capital building of the community of Madrid, is Kilometer Zero, a plaque showing the point where the measuring of national highways begins. Both the bear statue, and Km. Zero are common meeting spots for friends. The giant neon Tío Pepe sign above the plaza is also a famous fixture of this area. New Year’s celebrations are broadcast from Sol every year with the ringing of the clock bringing in the new year.

Palacio Real(Royal Palace) is an enormous palace, the biggest one in Europe in its kind, with scorching plains of concrete around it and the Real Armorial (Royal Armory), a two-story collection of medieval weapons and armor. Though it is the official residence of the King of Spain, the royal family does not actually reside here and it is generally used only for state ceremonies. The Royal Palace is considered to be one of the most emblematic and beautiful buildings in Madrid, not only for its location but also for its architecture and the artistic treasures to be found in its rooms. The façades of the palace measure 130 meters long and 33 meters high with 870 windows and 240 balconies opening on to the facades and courtyard. It has a surface area of 100,000 square meters with 44 stairways and more than 30 principal rooms.

Spanish Main

Definition

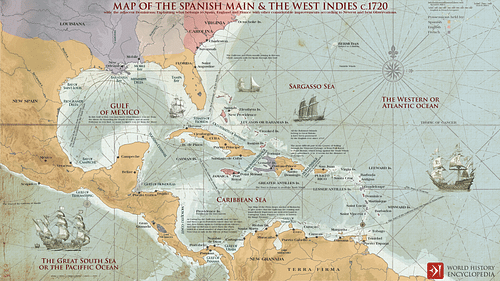

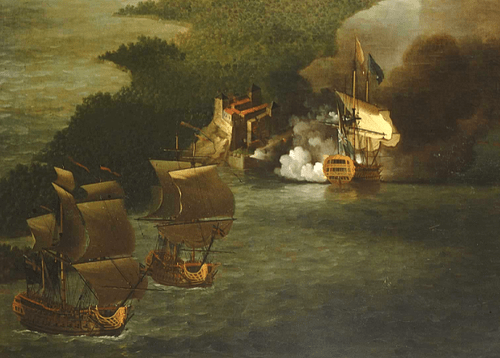

The Spanish Main refers, in its widest sense, to the Spanish Empire in the Americas from Florida in the north to the northern coast of Brazil in the south, including the Caribbean. The term was initially more limited and referred only to the mainland Spanish territories in northern South America. It was a name particularly popular with writers of pirate fiction as a handy and romantic term to cover the field of operation of privateers, buccaneers, and pirates from the 16th to 18th centuries.

Geographical Area

The term ‘Spanish Main’ was applied to Spanish colonial possessions in the Americas from around 1520 to 1730 and the end of the Golden Age of Piracy. At first, it had a more limited meaning. The term literally meant the «mainland of the Spanish Empire» and derived from the Spanish Tierra Firme, meaning the «mainland». Consequently, the expression was used by English privateers in the 16th century to mean only the northern coast of South America (approximately from Panama to Trinidad), although the coastal waters thereof were also included. The Caribbean islands were not then included within the term’s geographical reference since these were obviously islands and not the American mainland. The buccaneers of the 17th century then used ‘Spanish Main’ to refer to the Caribbean Sea, in effect, inverting the original meaning. 18th-century fiction writers began to use the term even more indiscriminately to mean all of the Spanish Empire from Florida in the north to the border with Portuguese Brazil in the south. It also now referred to the entire ocean in that area and so came to include all of the Caribbean with the exception of the Lesser Antilles, which had been colonised by other European powers.

Advertisement

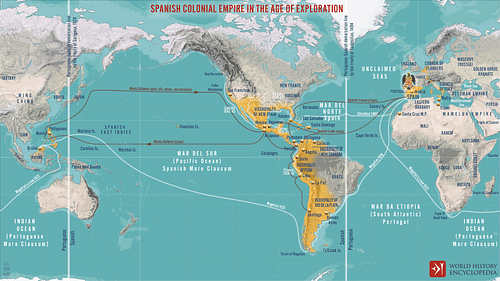

The Spanish Empire

In 1492, Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) sailed across the Atlantic in the service of the Spanish Crown, and instead of finding a route to Asia as he had hoped, he encountered the Americas. Columbus himself embarked on more voyages of exploration, and he was followed by others. Spain’s only real rival in the race to exploit the riches of the Americas was the Portuguese, but the two nations audaciously carved up the globe to create two spheres of interest. The division was set by the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas and extended in the 1529 Treaty of Zaragoça (Saragosa).

In 1494, a Spanish settlement was founded at La Isabela on the island of Hispaniola (modern Dominican Republic/Haiti). In 1498 Santo Domingo was founded on the island. In 1508 Puerto Rico was settled; in 1511 Cuba followed. Cattle, horses, and mules were introduced and bred. Plantations were created growing sugar cane, just as the Portuguese had been doing in the Atlantic islands like Madeira. Tobacco was another booming plantation crop. Slaves were used to work these plantations, both indigenous peoples and West Africans. Perhaps 2 million African slaves were shipped to the Spanish Main in the 16th and 17th centuries. Having established themselves in the Caribbean, the Spanish then sent tentative expeditions to the American mainland, starting in Panama where the Pacific Ocean was first seen by European eyes, those of Vasco Núñez de Balboa, in 1513. The colonisation of the ‘Spanish Indies’, as the Americas was then known, had begun.

Advertisement

The indigenous peoples of the coast very often fought back this tide of colonisation, resorting to tactics like ambush in the face of a merciless enemy with weapons of technology centuries ahead, but the visitors from the Old World were here to stay. Native peoples were ruthlessly robbed, butchered, or enslaved; those that remained alive were taught the religion of these strange men for afar, the explorers, the priests, and the hidalgo adventurers. In just one example, the Arawak Indians of the Caribbean were wiped out within a generation by the sword, exploitation, and European diseases. The dreadful pattern of conquest was set.

Spanish forces, the Conquistadores, acted upon rumours of fabled cities of gold deep in the American interior and so they attacked and destroyed the Aztec civilization in Mexico from 1519 onwards. Weakened from within by political factions, the Aztecs were defeated by superior weaponry, cavalry, and tactics. Once again, diseases ripped through the population. The Spanish cleverly allied themselves with long-time rivals to the Aztecs such as the Tarascan civilization, and the overstretched and often brutal Aztec Empire collapsed, to be replaced by an even more brutal new order. The Conquistadores’ leader was Hernán Cortés (1485-1547) whose religious zeal was matched by his thirst for riches and glory. The wealth of ancient Mexico was ruthlessly plundered as ships began to transport treasure back to Spain. The Aztec capital Tenochtitlan was made the new capital of the colony of New Spain, and Cortés was made its first governor in May 1523. In 1535, Don Antonio de Mendoza was made the first viceroy of New Spain.

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

Next was the turn of central America and then South America. In 1532, a Spanish force led by Francisco Pizarro (1478-1542) encountered the Inca Empire, which, stretching from Quito to Santiago, was the largest in the world. Once again, a combination of superior weapons and internal disputes saw a young and fragile empire totally collapse within a generation. Most decisive of all were the European diseases like smallpox which had already spread from Mexico to South America even before the Spanish themselves arrived. In the greatest humanitarian disaster to ever hit the Americas, a staggering 65-90% of the population would die from this invisible enemy. For the Spanish at the time, the astonishing fact was the sheer quantity of gold and silver they saw in temples, houses, and on the bodies of the Incas themselves. With the fall of Cuzco in November 1533 and the installation of a puppet ruler, the Spanish thought they were well on the way to controlling a vast new region of the world. However, the new order had just as many practical difficulties as the old one in controlling a vast geographical area with a myriad of different peoples, cultures, and languages. Rebellions and wars bedevilled the Spanish until 1572 and the execution of the last claimant to the Inca throne.

Stripping the Americas

The Spanish established colonial government based on a system of principalities headed by a governor or viceroy. They also built fortifications to protect themselves from counter-attacks as the Spanish Empire stripped the Americas of anything valuable, indiscriminately melting down objects of gold and silver, in particular. When these easy sources were exhausted, trade was pursued, and natural resources were exploited like timber, pearls, and gems. Silver was acquired from mines in Peru and Mexico, both of which were worked using slave labour. The metal was frequently minted into pesos or pieces of eight, a coin that became the de facto international currency of the Americas.

Advertisement

The Spanish insisted on a trade monopoly in their empire and would not permit other European merchants to buy and sell goods to the newly growing colonial towns across the Americas. European rivals instead set their covetous eyes on the two annual treasure fleets of Spanish galleons that took the riches of the Americas to Spain (c. 1520-1789). As Spain also shipped precious eastern goods in the Manila galleons from the Philippines to Acapulco, Mexico (1565 to 1815), the Atlantic treasure fleets, besides gold, silver, and gems, also transported a fortune in silk, spices, and porcelain. In the first century of conquest, the Spanish extracted an astonishing 10.5 million troy ounces of gold from South America. In terms of silver, 25,000 tons were shipped to Spain by 1600. In addition, on average 3 million silver pesos went back to the Philippines each year to buy goods to fill up the Manila galleons. The relative rarity of silver in China meant that it could be used to purchase twice as much gold in the Far East as one could buy with the same amount of silver in Europe. The Spanish were not only extracting great riches from the Americas, they were shifting commodities around the globe to make even more profit.

A tempting target, attacks on the Spanish treasure fleets were unofficially endorsed by rival European governments to weaken Spain and persuade it to open up the Americas to trade. An escort and convoy system was largely successful in protecting the treasure fleets, but when the privateers did capture a prize, it was a huge one. Another tempting target was the ports where these riches were accumulated ready for loading onto the treasure ships.

The Key Ports

By the 17th century, the Spanish Empire in the Americas was composed of the Viceroyalty of New Spain (Mexico and Central America) with the seat of the viceroy in Mexico City (formerly Tenochtitlan). The Viceroyalty of Peru (the former Inca territory) was established in 1543. New Granada (Venezuela and Colombia) had another viceroy from 1739, this one headquartered at Cartagena. The Viceroyalty of Rio de La Plata (Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay) was not formed until 1776. Panama and Honduras each had a governor, as did Cuba, Hispaniola, and Puerto Rico.

Advertisement

Mexico City might have been the administrative capital of Spanish America, but the heart of the Spanish Main in many ways was Havana, Cuba. It enjoyed the best strategic location in the Caribbean basin, and its governor was senior to those on the other Caribbean islands. Havana was also the gathering point for the treasure fleets before they sailed to Spain, and, from 1610, had the largest shipyard in the Americas. The French privateer Jacques de Sores brutally attacked Havana in July 1555, and this made the Spanish determined to protect their colonial jewel. The Fuerza Real was built in 1558, the first bastion fortress to be built in the Americas. The great Morro Castle was added from 1589. Now, no other pirate, privateer, or naval commander ever dared attack Havana and its 30,000 residents for nearly two centuries.

Cartagena, in what is today Colombia, was one of the most important ports on the Spanish Main because it was the collecting point for gold, silver, emeralds, and pearls from Colombia-Venezuela. For this reason, it was known as the ‘Queen of the Indies’. It was briefly captured by Francis Drake (c. 1540-1596) in 1586 and so was given much-improved fortifications in 1602, which made the port all but impregnable.

Another key treasure port was Portobelo (aka Puerto Bello) in Panama. From 1596, it replaced Nombre de Dios (founded 1510) as the collecting point for the huge quantities of silver gathered from the Potosi mines in Peru (discovered in 1545). The silver was brought in galleons from Peru to Panama (founded 1519) and then taken overland across the isthmus to Portobelo using mules. Portobelo was also the site of a large annual trade fair. Consequently, Portobelo was an irresistible target for foreign marauders. Francis Drake seized the silver mule train in 1573, loot that amounted to 15 tons of silver and 100,000 gold pesos (enough cash to build 30 warships of the period).

Advertisement

San Juan de Ulúa was the fortress island that protected the harbour of Veracruz on the Atlantic coast of what is today Mexico, the third of the great treasure ports. Veracruz was founded in 1519 by Cortés, and it became the collection point both for silver gathered from Mexico and the eastern precious goods brought by the Manila galleons and transported across land to Veracruz. In 1568, San Juan de Ulúa was the site of an infamous Spanish attack on a trading fleet led by the Englishman John Hawkins (1532-1595 CE), a treacherous defeat the Elizabethan sea dogs used as an excuse to attack all things Spanish for the next half-century.

There were, of course, many other ports and towns throughout the Main. The heavily fortified St. Augustine in Florida helped maintain Spain’s tentative foothold on the coast of North America where they first had to resist the expansion of the French Huguenots who had settled in the area from 1562, and then the British who moved ever-southwards down America’s eastern coast. San Juan on Puerto Rico welcomed the Spanish treasure fleets to the Caribbean. Maracaibo on the coast of what is today Venezuela had around 4,000 residents and was the centre of the regional pearl trade.

Typically, all Spanish settlements in the Americas were laid out in a regular grid pattern of blocks and streets with a large central plaza for the community’s administrative and religious buildings. Royal regulations on town planning were issued from 1573. A mayor headed a group of councillors who governed the town, which was granted, as in Spain, the right to produce its own coat of arms. To help remind everyone where their ultimate loyalty lay, the royal coat of arms of Spain was presented over the town’s fortress gate and any official buildings.

The 17th-century Attacks

Into the 17th century, Spain’s colonial monopoly began to be challenged by other European powers, particularly in the Caribbean islands. England, France, and the Netherlands were all at war with Spain for much of the century, and the Americas was an important front given the funds that crossed the Atlantic. In addition, Spain’s navy was now third in size to the fleets of England and France. The English moved in on St. Kitts (aka Saint Christopher, 1623), Barbados (1624), Nevis (1628), Antigua, and Montserrat (1632). The French established themselves on Martinique and Guadeloupe in 1635. From 1599, Dutch ships took salt from Araya on the coast of Venezuela – a commodity vital for their herring industry – and they took a keen interest in the resources of Brazil. Of more direct concern to the Spanish Main was the Dutch colonisation of St. Eustatia, Tobago, and Curaçao between 1632 and 1634.

By the 1630s, there were some 18,000 Europeans living in the Lesser Antilles; by the 1660s, this figure had swelled to 100,000. Many of these East Caribbean islands were now used as bases by European powers to attack the Spanish Main and as havens for smugglers and pirates. The Spanish responded with regular attacks on the islands, but they were rarely successful in achieving anything except an increase in the animosity towards all things Spanish.

The British moved westwards, occupying Bermuda and the Bahamas, and when they took the strategic gem of Jamaica with its wonderful natural harbours in 1655, suddenly the entire Spanish Main was opened up to attacks. Key Spanish ports were persistently targeted by large amphibious forces of multinational privateers and adventurers known as buccaneers who were sponsored – either officially or otherwise – by the colonial authorities. The English buccaneer Henry Morgan (c. 1635-1688) sacked Panama in 1671, and he attacked and ransomed Portobelo in 1680. The Dutch privateer Laurens De Graaf (c. 1651-1702) attacked Veracruz in 1683 and managed to make off with the loot meant for a treasure fleet. A large French combined naval and pirate force captured Cartagena in 1697, the last major buccaneer raid before a formal peace was agreed between Spain, England, France, and the Netherlands. The Spanish responded to these setbacks by building bigger and better fortifications with city walls and suitably enlarged garrisons to man them.

The 18th-century Attacks

The Spanish Empire did revive from its somewhat dilapidated state. King Charles III of Spain (r. 1759-1788) was instrumental in overseeing a massive reinvestment across the Spanish Main, particularly in terms of fortifications and a new system of rotation which saw local garrisons boosted by an influx of better-trained and better-equipped troops from Europe. These forces were commanded by various captain-generals headquartered at the major ports. Defence of the empire, however, was an ongoing battle and a hugely expensive one that seemed to have no end.

In the mid-18th century, the British Admiralty specifically ordered its fleet commanders «to destroy the Spanish settlements in West Indies and distress their shipping by any method whatever» (Wood, 164). The Royal Navy even captured fortress Havana in 1762, but it was returned the next year. The 1763 Treaty of Paris saw Spain give Florida to Britain (they regained it in 1783) but receive in return a slice of French Louisiana. In 1800, Louisiana was ceded to France, but it ended up in the hands of the United States by 1804. The European powers were beginning to arrange their colonial interests like chess pieces, occasionally attempting bold strikes, sometimes making retreats, or biding their time to see how this multiplayer game of empires developed. Meanwhile, the United States, Mexicans, and others eyed which parts of the board they would claim for themselves irrespective of what pieces were sitting where.

Spanish Decline

Into the 19th century, not only did the Spanish have to deal with attacks from rival European powers but the world was also moving on rapidly both politically and economically. They now faced far greater threats from indigenous peoples in the Americas. Colombian rebel forces, for example, besieged and took Cartagena in 1815 and 1821. The Latin American nations declared independence from Spain through the 1820s. There were also threats from rising powers like the United States in the north. In 1819-21, Florida was ceded to the U.S. and for the remainder of the 19th century, the Spanish were left with only Cuba and Puerto Rico.

World trade had also opened up even further, and now the Far East was contributing commodities such as tea and opium to the world economy. India and Brazil were also growing fast, and the plantations of North America, South America, and the Caribbean – all fuelled by the horrific business of slavery – were flooding the world with sugar, tobacco, coffee, and cotton. The days when Spain could monopolise half the world’s trade and the Spanish Main seemed the treasure house of the world were but a distant memory.