What is cash flow

What is cash flow

Cash Flow Definition

Adam Hayes, Ph.D., CFA, is a financial writer with 15+ years Wall Street experience as a derivatives trader. Besides his extensive derivative trading expertise, Adam is an expert in economics and behavioral finance. Adam received his master’s in economics from The New School for Social Research and his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in sociology. He is a CFA charterholder as well as holding FINRA Series 7, 55 & 63 licenses. He currently researches and teaches economic sociology and the social studies of finance at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

What Is Cash Flow?

The term cash flow refers to the net amount of cash and cash equivalents being transferred in and out of a company. Cash received represents inflows, while money spent represents outflows. A company’s ability to create value for shareholders is fundamentally determined by its ability to generate positive cash flows or, more specifically, to maximize long-term free cash flow (FCF). FCF is the cash generated by a company from its normal business operations after subtracting any money spent on capital expenditures (CapEx).

Key Takeaways

Understanding Cash Flow

How Cash Flow Works

In simple terms, cash flow is the amount of cash that comes in and goes out of a company. Businesses take in money from sales as revenues and spend money on expenses. They may also receive income from interest, investments, royalties, and licensing agreements and sell products on credit, expecting to actually receive the cash owed at a late date.

Assessing the amounts, timing, and uncertainty of cash flows, along with where they originate and where they go, is one of the most important objectives of financial reporting. It is essential for assessing a company’s liquidity, flexibility, and overall financial performance.

Positive cash flow indicates that a company’s liquid assets are increasing, enabling it to cover obligations, reinvest in its business, return money to shareholders, pay expenses, and provide a buffer against future financial challenges. Companies with strong financial flexibility can take advantage of profitable investments. They also fare better in downturns, by avoiding the costs of financial distress.

Cash flows can be analyzed using the cash flow statement. The main purpose of a cash flow statement is to provide a standard financial statement that reports on a company’s sources and usage of cash over a specified time period. Corporate management, analysts, and investors are able to use it to determine how well a company can earn cash to pay its debts and manage its operating expenses. The cash flow statement is one of the most important financial statements issued by a company, along with the balance sheet and income statement.

Cash flow can be negative when outflows are higher than a company’s inflows.

Special Considerations

As noted above, there are three critical parts of a company’s financial statements:

But the cash flow does not necessarily show all the company’s expenses. That’s because not all expenses the company accrues are paid right away. Although the company may incur liabilities, any payments toward these liabilities are not recorded as a cash outflow until the transaction occurs.

The first item to note on the cash flow statement is the bottom line item. This is likely to be recorded as the net increase/decrease in cash and cash equivalents (CCE) (CCE). The bottom line reports the overall change in the company’s cash and its equivalents (the assets that can be immediately converted into cash) over the last period.

If you check under current assets on the balance sheet, that’s where you’ll find CCE. If you take the difference between the current CCE and that of the previous year or the previous quarter, you should have the same number as the number at the bottom of the statement of cash flows.

Types of Cash Flow

Cash Flows From Operations (CFO)

Cash flow from operations (CFO), or operating cash flow, describes money flows involved directly with the production and sale of goods from ordinary operations. CFO indicates whether or not a company has enough funds coming in to pay its bills or operating expenses. In other words, there must be more operating cash inflows than cash outflows for a company to be financially viable in the long term.

Operating cash flow is calculated by taking cash received from sales and subtracting operating expenses that were paid in cash for the period. Operating cash flow is recorded on a company’s cash flow statement, which is reported both on a quarterly and annual basis. Operating cash flow indicates whether a company can generate enough cash flow to maintain and expand operations, but it can also indicate when a company may need external financing for capital expansion.

Note that CFO is useful in segregating sales from cash received. If, for example, a company generated a large sale from a client, it would boost revenue and earnings. However, the additional revenue doesn’t necessarily improve cash flow if there is difficulty collecting the payment from the customer.

Cash Flows From Investing (CFI)

Cash flow from investing (CFI) or investing cash flow reports how much cash has been generated or spent from various investment-related activities in a specific period. Investing activities include purchases of speculative assets, investments in securities, or the sale of securities or assets.

Negative cash flow from investing activities might be due to significant amounts of cash being invested in the long-term health of the company, such as research and development (R&D), and is not always a warning sign.

Cash Flows From Financing (CFF)

Cash flows from financing (CFF), or financing cash flow, shows the net flows of cash that are used to fund the company and its capital. Financing activities include transactions involving issuing debt, equity, and paying dividends. Cash flow from financing activities provide investors with insight into a company’s financial strength and how well a company’s capital structure is managed.

Cash Flow vs. Profit

Contrary to what you may think, cash flow isn’t the same as profit. It isn’t uncommon to have these two terms confused because they seem very similar. Remember that cash flow is the money that goes in and out of a business.

Profit, on the other hand, is specifically used to measure a company’s financial success or how much money it makes overall. This is the amount of money that is left after a company pays off all its obligations. Profit is whatever is left after subtracting a company’s expenses from its revenues.

How to Analyze Cash Flows

Using the cash flow statement in conjunction with other financial statements can help analysts and investors arrive at various metrics and ratios used to make informed decisions and recommendations. The following are some of the most common ways for cash flow analysis.

Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR)

Even profitable companies can fail if their operating activities do not generate enough cash to stay liquid. This can happen if profits are tied up in outstanding accounts receivable (AR) and overstocked inventory, or if a company spends too much on capital expenditures (CapEx).

Investors and creditors, therefore, want to know if the company has enough CCE to settle short-term liabilities. To see if a company can meet its current liabilities with the cash it generates from operations, analysts look at the debt service coverage ratio (DSCR).

Debt Service Coverage Ratio = Net Operating Income / Short-Term Debt Obligations (or Debt Service)

But liquidity only tells us so much. A company might have lots of cash because it is mortgaging its future growth potential by selling off its long-term assets or taking on unsustainable levels of debt.

Free Cash Flow (FCF)

Analysts look at free cash flow (FCF) to understand the true profitability of a business. FCF is a really useful measure of financial performance and tells a better story than net income because it shows what money the company has left over to expand the business or return to shareholders, after paying dividends, buying back stock, or paying off debt.

Unlevered Free Cash Flow (UFCF)

Use unlevered free cash flow (UFCF) for a measure of the gross FCF generated by a firm. This is a company’s cash flow excluding interest payments, and it shows how much cash is available to the firm before taking financial obligations into account. The difference between levered and unlevered FCF shows if the business is overextended or operating with a healthy amount of debt.

Example of Cash Flow

Below is a reproduction of Walmart’s cash flow statement for the fiscal year ending on Jan. 31, 2019. All amounts are in millions of U.S. dollars.

| Walmart Statement of Cash Flows (2019) | |

|---|---|

| Cash flows from operating activities: | |

| Consolidated net income | 7,179 |

| (Income) loss from discontinued operations, net of income taxes | — |

| Income from continuing operations | 7,179 |

| Adjustments to reconcile consolidated net income to net cash provided by operating activities: | |

| Unrealized (gains) and losses | 3,516 |

| (Gains) and losses for disposal of business operations | 4,850 |

| Depreciation and amortization | 10,678 |

| Deferred income taxes | (499) |

| Other operating activities | 1,734 |

| Changes in certain assets and liabilities: | |

| Receivables, net | (368) |

| Inventories | (1,311) |

| Accounts payable | 1,831 |

| Accrued liabilities | 183 |

| Accrued income taxes | (40) |

| Net cash provided by operating activities | 27,753 |

| Cash flows from investing activities: | |

| Payments for property and equipment | (10,344) |

| Proceeds from the disposal of property and equipment | 519 |

| Proceeds from the disposal of certain operations | 876 |

| Payments for business acquisitions, net of cash acquired | (14,656) |

| Other investing activities | (431) |

| Net cash used in investing activities | (24,036) |

| Cash flows from financing activities: | |

| Net change in short-term borrowings | (53) |

| Proceeds from issuance of long-term debt | 15,872 |

| Payments of long-term debt | (3,784) |

| Dividends paid | (6,102) |

| Purchase of company stock | (7,410) |

| Dividends paid to noncontrolling interest | (431) |

| Other financing activities | (629) |

| Net cash used in financing activities | (2,537) |

| Effect of exchange rates on cash and cash equivalents | (438) |

| Net increase (decrease) in cash and cash equivalents | 742 |

| Cash and cash equivalents at beginning of year | 7,014 |

| Cash and cash equivalents at end of year | 7,756 |

The final line in the cash flow statement, «cash and cash equivalents at end of year,» is the same as «cash and cash equivalents,» the first line under current assets in the balance sheet. The first number in the cash flow statement, «consolidated net income,» is the same as the bottom line, «income from continuing operations» on the income statement.

Because the cash flow statement only counts liquid assets in the form of CCE, it makes adjustments to operating income in order to arrive at the net change in cash. Depreciation and amortization expense appear on the income statement in order to give a realistic picture of the decreasing value of assets over their useful life. Operating cash flows, however, only consider transactions that impact cash, so these adjustments are reversed.

This increase would have shown up in operating income as additional revenue, but the cash wasn’t received yet by year-end. Thus, the increase in receivables needed to be reversed out to show the net cash impact of sales during the year. The same elimination occurs for current liabilities in order to arrive at the cash flow from operating activities figure.

Investments in property, plant, and equipment (PP&E) and acquisitions of other businesses are accounted for in the cash flow from the investing activities section. Proceeds from issuing long-term debt, debt repayments, and dividends paid out are accounted for in the cash flow from financing activities section.

How Are Cash Flows Different Than Revenues?

Revenues refer to the income earned from selling goods and services. If an item is sold on credit or via a subscription payment plan, money may not yet be received from those sales and are booked as accounts receivable. But these do not represent actual cash flows into the company at the time. Cash flows also track outflows as well as inflows and categorize them with regard to the source or use.

What Are the Three Categories of Cash Flows?

The three types of cash flows are operating cash flows, cash flows from investments, and cash flows from financing.

Operating cash flows are generated from the normal operations of a business, including money taken in from sales and money spent on cost of goods sold (COGS), along with other operational expenses such as overhead and salaries.

Cash flows from investments include money spent on purchasing securities to be held as investments such as stocks or bonds in other companies or in Treasuries. Inflows are generated by interest and dividends paid on these holdings.

Cash flows from financing are the costs of raising capital, such as shares or bonds that a company issues or any loans it takes out.

What Is Free Cash Flow and Why Is It Important?

Free cash flow is the cash left over after a company pays for its operating expenses and CapEx. It is the money that remains after paying for items like payroll, rent, and taxes. Companies are free to use FCF as they please.

Knowing how to calculate FCF and analyze it helps a company with its cash management and will provide investors with insight into a company’s financials, helping them make better investment decisions.

FCF is an important measurement since it shows how efficient a company is at generating cash.

Do Companies Need to Report a Cash Flow Statement?

The cash flow statement complements the balance sheet and income statement and is a mandatory part of a public company’s financial reporting requirements since 1987.

Why Is the Price-to-Cash Flows Ratio Used?

The price-to-cash flow (P/CF) ratio is a stock multiple that measures the value of a stock’s price relative to its operating cash flow per share. This ratio uses operating cash flow, which adds back non-cash expenses such as depreciation and amortization to net income.

P/CF is especially useful for valuing stocks that have positive cash flow but are not profitable because of large non-cash charges.

Cash Flow Definition: What is it? Importance, Types and Example

Vivien Thuri

Cash flow is an extremely important measure when it comes to assessing the financial health of your business. 60% of businesses have reported experiencing cash flow issues and 89% of business owners have seen a negative impact on their business because of cash flow problems.¹

Having a clear understanding of what cash flow is, why it’s important, and the different types of cash flow can be incredibly helpful in understanding and improving business performance.

This article will take you through a definition of what cash flow is and what types of cash flow businesses should be looking at.

What is cash flow, and why is it important

The basic definition of cash flow refers to the amount of money that is coming in and out of the business. ²

Cash flow is crucial for a business for many different reasons.

Businesses are required to report a cash flow statement as part of their financial documents.³

It’s a crucial metric, used when reviewing and monitoring a business’ financial performance and determining the next steps in growth.

Particularly for international businesses, it can be a useful metric to help rethink costs, understand multi-currency effects of supplier payments, make investments or obtain a loan.

Having a clear understanding of how cash is being received and spent, and to understand overall cash flow management is vital to mitigate any cash flow problems before they arise and damage the business.

Cash inflow

Cash inflow refers to the money a business receives.⁴ Essentially, it’s the income that is generated through the business and its daily activities.

Cash inflow is incredibly important because it is how revenue and profit is generated. A positive inflow of cash, helps a business grow while also maintaining its expenses.

Sources of cash inflow can include:

dividends or returns received from investments

any financial activity a business partakes in, that generates revenue and interest received from domestic and foreign businesses

As businesses generate cash, they can develop additional strategies by partnering or acquiring other companies to increase cash inflow further.

Cash outflow

Cash outflow refers to the spent money, that moves out of the business to help it run and operate.⁴

Cash outflow may include:

office rent across different locations and countries

any liabilities the business holds

supplier payments and payroll expenses in multiple countries

Multi-currency payments, in particular, can get difficult to manage when monitoring cash outflow, if different methods are being used.

| Multi-currency cash flow made easy for your business. Open a Wise Business account to make international payments and cash flow management convenient. |

|---|

Positive and Negative cash flow

When businesses have a positive cash flow, it means they have increased their liquid assets.⁵

Positive cash flow occurs when a business is left with cash even after paying all cash outflow expenses such as operations and debt.

It means that the business is profitable and that companies have the ability to grow and reinvest as needed with positive cash.

For example, if operations and other costs lead to more outflow than cash coming in, that means the business is not profitable, leading to dire consequences down the line, such as bankruptcy.

However, if the negative cash flow is occurring because the business is investing in different areas to bolster the long-term health of the business, then negative cash flow may not be a sign of trouble.

Types of cash flow

There are three types of cash flow used to measure the business’s financial health across various aspects.

| Cash flow type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Operating cash flow (OCF) | Operating cash flow refers to the cash moving in and out of the business, as part of maintaining normal business operations. Operating cash flow can include inventory management, rent and office expenses, payroll and more. |

| Cash flow from Investing (CFI) | Cash flow from investing refers to cash flow generated from any investing activities a business partakes in. Cash flow from investing can include purchasing assets and securities for the business as an investment or selling assets and securities to generate cash. |

| Cash flow from Financing (CFF) | Cash flow from financing includes any revenue spent or received relating to financing such as debt, dividends, and equity. For example, cash flow from financing includes issuing and repaying equity, paying out dividends, and issuing or paying back debt. |

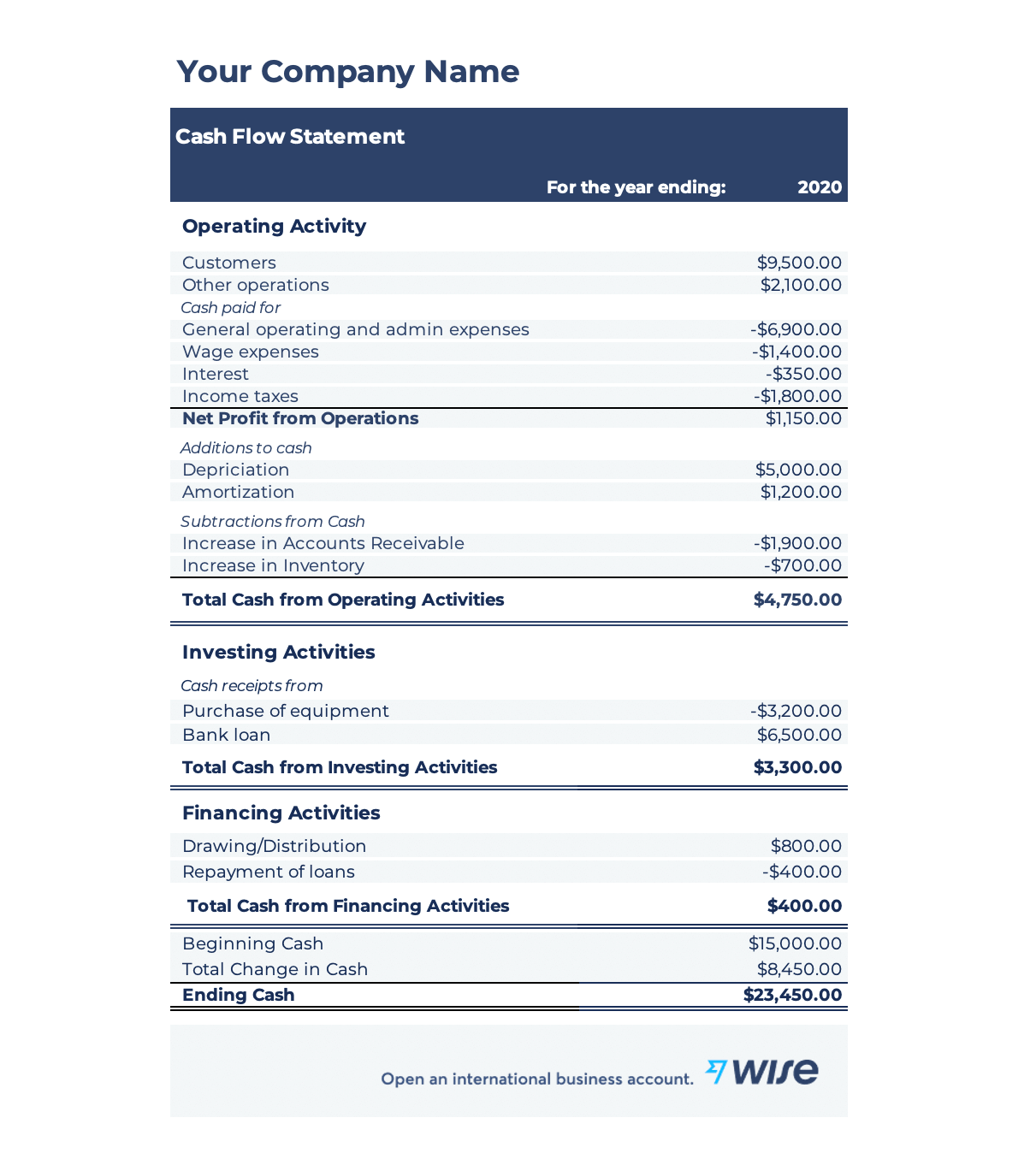

Cash flow example

Many examples of cash flow statements are available from large and small companies to better understand how they measure cash inflow and outflow.

Here is an example of a cash flow statement.

As you can see, using the Wise cash flow template, the cash flow statement includes the different types of cash flow across different parts of the business to understand its financial performance.

| If you’d like to generate your own cash flow statement, use the free Wise cash flow template. |

|---|

Take control of your business operations with the world’s most international account

Wise enables businesses to gain more control over their spending and monitor cash flow more thoroughly. Wise multi-currency accounts allow you to manage all your currencies and subscriptions in one place.

With Wise, you can use one account for more than 50 currencies to connect with customers and suppliers overseas. Pay employees and merchants around the world with one click, easily.

On top of that, Wise makes payments fast and provides upfront, transparent fees. You’ll always get the mid-market rate while saving up to 19x compared to PayPal.

All sources checked 29 September 2021

This publication is provided for general information purposes only and is not intended to cover every aspect of the topics with which it deals. It is not intended to amount to advice on which you should rely. You must obtain professional or specialist advice before taking, or refraining from, any action on the basis of the content in this publication. The information in this publication does not constitute legal, tax or other professional advice from TransferWise Limited or its affiliates. Prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome. We make no representations, warranties or guarantees, whether express or implied, that the content in the publication is accurate, complete or up to date.

© The Balance, 2018

Cash flow is the money that is moving (flowing) in and out of your business in a month. Although it does sometimes seem that cash flow only goes one way—out of the business—it does flow both ways.

Cash Flow Help During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Several forms of coronavirus relief are available to small businesses affected by the pandemic:

Congress has extended to May 31, 2021, the deadline to apply for PPP funds. The SBA will be processing applications until June 30.

If you need cash to pay employees, you might be eligible for an Employee Retention tax credit, set up to encourage businesses to keep employees. You can take the tax credit on your quarterly employment tax return on Form 941 or you can request an advance from the IRS.

See this article on Small Business Relief Options During COVID-19 for more ways to get help for your business if you’ve been affected by the pandemic.

Cash vs. Real Cash

For some businesses, like restaurants and some retailers, cash is really cash: currency and paper money. The business takes cash from customers and sometimes pays its bills in cash. Cash businesses have a special issue with keeping track of cash flow, especially since they may not track income unless there are invoices or other paperwork.

Think of cash flow as a picture of your business checking account over time. If more money is coming in than is going out, you are in a «positive cash flow» situation and you have enough to pay your bills. If more cash is going out than is coming in, you are in danger of being overdrawn, and you will need to find money to cover your overdrafts.

Cash businesses are more at risk of being audited by the IRS because it’s easy to hide cash income and not report it.

Why Cash Flow Is So Important

Lack of cash is one of the biggest reasons small businesses fail. It’s also called «running out of money,» and it will shut you down faster than anything else.

Starting a Business: Dealing with cash flow issues is most difficult when you are starting a business. You have many expenses, and money is going out fast. And you may have no sales or customers who are paying you. You will need some other sources of cash, like through a temporary line of credit, to get you going and on to a positive cash flow situation.

The first six months of a business are a crucial time period for cash flow. If you don’t have enough cash to carry you through this time, your chances for success aren’t good. Suppliers often won’t give credit to new businesses, and your customers may want to pay on credit, giving you a «cash crunch» to deal with.

In estimating your cash flow needs for your startup, include your personal living expenses that will need to come out of the business. The less you need to take from your business for personal costs, the more you can devote to your business during the crucial startup time.

Seasonal Business: Cash flow is particularly important for seasonal businesses—those that have a large fluctuation of business at different times of the year, like holiday businesses and summer businesses. Managing cash flow in this type of business is tricky, but it can be done, with diligence.

Cash Vs. Profit: It’s possible for your business to make a profit but have no cash. How can that happen? The short answer is that profit is an accounting concept, while cash, as noted above, is the amount in the business checking account. Profit doesn’t pay the bills. You can have assets, like accounts receivable (money owed to you by customers), but if you can’t collect what’s owed, you won’t have cash.

Tips for Managing Your Cash Flow

Here are some ways to better manage your cash flow to avoid a cash flow emergency:

Control inventory. Having too much inventory ties up cash. Keep track of inventory so you can estimate your needs better.

Collect receivables. Set up a collections schedule, using an accounts receivable aging report as a guide. Follow up on non-payers.

End Unprofitable Relationships. Decide when it’s time to end a relationship with someone who never pays.

Using a Cash Flow Statement

The best way to keep track of cash flow in your business is to run a cash flow report. This report shows the cash you received and the cash paid out to show your business’s cash position at the end of every month.

At times, you may need to keep track of cash flow on a weekly, maybe even a daily, basis.

To dig deeper into this tip:

If this monthly cash shortage continues for several months, you’ll get further and further behind.

Four Easy Ways to Get a Cash Flow Statement

If you have time to do only one business analysis every month, make it a cash flow statement to keep track of your cash position.

Getting Temporary Cash Flow Help

Many businesses get help with temporary cash flow shortages by setting up a working capital line of credit. A business credit line for working capital works in a different way from a loan.

Understanding the Cash Flow Statement

Natalya Yashina is a CPA, DASM with over 12 years of experience in accounting including public accounting, financial reporting, and accounting policies. She is a member of the Virginia CPA Society Accounting and Advisory Committee and serves on the Board of Directors for the Virginia CPA Society Educational Foundation.She is the founder and CEO of Capital Accounting Advisory, LLC, an accounting advisory firm that offers technical accounting, project management, and training services and solutions.

The cash flow statement (CFS), is a financial statement that summarizes the movement of cash and cash equivalents (CCE) that come in and go out of a company. The CFS measures how well a company manages its cash position, meaning how well the company generates cash to pay its debt obligations and fund its operating expenses. As one of the three main financial statements, the CFS complements the balance sheet and the income statement. In this article, we’ll show you how the CFS is structured and how you can use it when analyzing a company.

Key Takeaways

What Is a Cash Flow Statement?

How the Cash Flow Statement Is Used

The cash flow statement paints a picture as to how a company’s operations are running, where its money comes from, and how money is being spent. Also known as the statement of cash flows, the CFS helps its creditors determine how much cash is available (referred to as liquidity) for the company to fund its operating expenses and pay down its debts. The CFS is equally as important to investors because it tells them whether a company is on solid financial ground. As such, they can use the statement to make better, more informed decisions about their investments.

Structure of the Cash Flow Statement

The main components of the cash flow statement are:

Cash from Operating Activities

The operating activities on the CFS include any sources and uses of cash from business activities. In other words, it reflects how much cash is generated from a company’s products or services.

These operating activities might include:

In the case of a trading portfolio or an investment company, receipts from the sale of loans, debt, or equity instruments are also included because it is a business activity.

Changes made in cash, accounts receivable, depreciation, inventory, and accounts payable are generally reflected in cash from operations.

Cash from Investing Activities

Investing activities include any sources and uses of cash from a company’s investments. Purchases or sales of assets, loans made to vendors or received from customers, or any payments related to mergers and acquisitions (M&A) are included in this category. In short, changes in equipment, assets, or investments relate to cash from investing.

Changes in cash from investing are usually considered cash-out items because cash is used to buy new equipment, buildings, or short-term assets such as marketable securities. But when a company divests an asset, the transaction is considered cash-in for calculating cash from investing.

Cash from Financing Activities

Cash from financing activities includes the sources of cash from investors and banks, as well as the way cash is paid to shareholders. This includes any dividends, payments for stock repurchases, and repayment of debt principal (loans) that are made by the company.

Changes in cash from financing are cash-in when capital is raised and cash-out when dividends are paid. Thus, if a company issues a bond to the public, the company receives cash financing. However, when interest is paid to bondholders, the company is reducing its cash. And remember, although interest is a cash-out expense, it is reported as an operating activity—not a financing activity.

How Cash Flow Is Calculated

There are two methods of calculating cash flow: the direct method and the indirect method.

Direct Cash Flow Method

The direct method adds up all of the cash payments and receipts, including cash paid to suppliers, cash receipts from customers, and cash paid out in salaries. This method of CFS is easier for very small businesses that use the cash basis accounting method.

These figures can also be calculated by using the beginning and ending balances of a variety of asset and liability accounts and examining the net decrease or increase in the accounts. It is presented in a straightforward manner.

Most companies use the accrual basis accounting method. In these cases, revenue is recognized when it is earned rather than when it is received. This causes a disconnect between net income and actual cash flow because not all transactions in net income on the income statement involve actual cash items. Therefore, certain items must be reevaluated when calculating cash flow from operations.

Indirect Cash Flow Method

With the indirect method, cash flow is calculated by adjusting net income by adding or subtracting differences resulting from non-cash transactions. Non-cash items show up in the changes to a company’s assets and liabilities on the balance sheet from one period to the next. Therefore, the accountant will identify any increases and decreases to asset and liability accounts that need to be added back to or removed from the net income figure, in order to identify an accurate cash inflow or outflow.

Changes in accounts receivable (AR) on the balance sheet from one accounting period to the next must be reflected in cash flow:

What about changes in a company’s inventory? Here’s how they are accounted for on the CFS:

The same logic holds true for taxes payable, salaries, and prepaid insurance. If something has been paid off, then the difference in the value owed from one year to the next has to be subtracted from net income. If there is an amount that is still owed, then any differences will have to be added to net earnings.

Limitations of the Cash Flow Statement

Negative cash flow should not automatically raise a red flag without further analysis. Poor cash flow is sometimes the result of a company’s decision to expand its business at a certain point in time, which would be a good thing for the future.

Analyzing changes in cash flow from one period to the next gives the investor a better idea of how the company is performing, and whether a company may be on the brink of bankruptcy or success. The CFS should also be considered in unison with the other two financial statements.

The indirect cash flow method allows for a reconciliation between two other financial statements: the income statement and balance sheet.

Cash Flow Statement vs. Income Statement vs. Balance Sheet

The cash flow statement measures the performance of a company over a period of time. But it is not as easily manipulated by the timing of non-cash transactions. As noted above, the CFS can be derived from the income statement and the balance sheet. Net earnings from the income statement are the figure from which the information on the CFS is deduced. But they only factor into determining the operating activities section of the CFS. As such, net earnings have nothing to do with the investing or financial activities sections of the CFS.

The income statement includes depreciation expense, which doesn’t actually have an associated cash outflow. It is simply an allocation of the cost of an asset over its useful life. A company has some leeway to choose its depreciation method, which modifies the depreciation expense reported on the income statement. The CFS, on the other hand, is a measure of true inflows and outflows that cannot be as easily manipulated.

As for the balance sheet, the net cash flow reported on the CFS should equal the net change in the various line items reported on the balance sheet. This excludes cash and cash equivalents and non-cash accounts, such as accumulated depreciation and accumulated amortization. For example, if you calculate cash flow for 2019, make sure you use 2018 and 2019 balance sheets.

The CFS is distinct from the income statement and the balance sheet because it does not include the amount of future incoming and outgoing cash that has been recorded as revenues and expenses. Therefore, cash is not the same as net income, which includes cash sales as well as sales made on credit on the income statements.

Example of a Cash Flow Statement

Below is an example of a cash flow statement:

The purchasing of new equipment shows that the company has the cash to invest in itself. Finally, the amount of cash available to the company should ease investors’ minds regarding the notes payable, as cash is plentiful to cover that future loan expense.

What Is the Difference Between Direct and Indirect Cash Flow Statements?

The difference lies in how the cash inflows and outflows are determined.

Using the direct method, actual cash inflows and outflows are known amounts. The cash flow statement is reported in a straightforward manner, using cash payments and receipts.

Using the indirect method, actual cash inflows and outflows do not have to be known. The indirect method begins with net income or loss from the income statement, then modifies the figure using balance sheet account increases and decreases, to compute implicit cash inflows and outflows.

Is the Indirect Method of the Cash Flow Statement Better Than the Direct Method?

Neither is necessarily better or worse. However, the indirect method also provides a means of reconciling items on the balance sheet to the net income on the income statement. As an accountant prepares the CFS using the indirect method, they can identify increases and decreases in the balance sheet that are the result of non-cash transactions.

It is useful to see the impact and relationship that accounts on the balance sheet have to the net income on the income statement, and it can provide a better understanding of the financial statements as a whole.

What Is Included in Cash and Cash Equivalents?

Cash and cash equivalents are consolidated into a single line item on a company’s balance sheet. It reports the value of a business’s assets that are currently cash or can be converted into cash within a short period of time, commonly 90 days. Cash and cash equivalents include currency, petty cash, bank accounts, and other highly liquid, short-term investments. Examples of cash equivalents include commercial paper, Treasury bills, and short-term government bonds with a maturity of three months or less.

The Bottom Line

A cash flow statement is a valuable measure of strength, profitability, and the long-term future outlook of a company. The CFS can help determine whether a company has enough liquidity or cash to pay its expenses. A company can use a CFS to predict future cash flow, which helps with budgeting matters.

For investors, the CFS reflects a company’s financial health, since typically the more cash that’s available for business operations, the better. However, this is not a rigid rule. Sometimes, a negative cash flow results from a company’s growth strategy in the form of expanding its operations.

By studying the CFS, an investor can get a clear picture of how much cash a company generates and gain a solid understanding of the financial well-being of a company.

What Is Cash Flow? Almost Everything You Need to Know

Become a master of business cash flow with this comprehensive guide—and watch your business thrive as a result.

Have you ever found yourself at month-end scrambling to find cash to cover your expenses? Are your expenses constantly higher than your cash on hand? Do you struggle to define “cash flow”? If you answered yes to any of these questions, chances are, business cash flow isn’t one of your areas of expertise.

You’re not alone. Many small business owners struggle with cash flow issues, for various reasons, including feast-or-famine cycles, slow work periods, late-paying clients, or unplanned expenses that throw their budgets out of whack.

Understanding business cash flow is the first step to ensuring that you have enough cash on hand to cover your expenses at any given time. But what, exactly, is cash flow? Why is it so important to your business? And what steps can you take to improve cash flow?

What Is Cash Flow?

Before we dive too deep into all things cash flow, let’s take a moment to define what, exactly, cash flow is. Simply put, cash flow is the total amount of money flowing in and out of your business.

When you have more money flowing into your business than out of your business, you have a positive cash flow. When you have more money flowing out of your business than you do coming in, you have a negative cash flow. (Negative cash flow is also sometimes called being “in the red.”)

Cash Flow vs. Profit and Revenue

It’s important to note that cash flow isn’t the same thing as profit or revenue. Cash flow measures all money coming into and going out of your business—not just money you make from normal business operations (revenue). Profit is revenue minus expenses, which also only accounts for cash flow from operations.

This means a business could have a positive cash flow and still be considered unprofitable—say, the cash inflows are from sources other than operations, such as borrowing.

Example:

Why Does Cash Flow Matter?

Now that you understand what cash flow is, it’s important to examine why positive cash flow is so critical to your business.

It keeps operations moving forward. Your business doesn’t stop running while you wait to get paid. Without sufficient cash on hand to cover your expenses, your business operations could come to a screeching halt. Understanding cash flow allows you to run your business in a way that balances cash in vs. cash out—which allows you to keep operations progressing.

It informs your business strategy. Understanding cash flow can help you make better strategic decisions for your business.

For example, let’s say you need to buy new equipment for your office. Calculating your business’s cash flow can help you make the best decision around when to buy the equipment and will help prevent a cash deficit in your business.

It helps you plan for the future. Digging into your cash flow data can also help you better plan for your business’ future. Consider this scenario: You own an artisanal ice cream shop and your company generates much more cash in the summer than the winter. Understanding your cash flow can help you set aside enough cash to cover your operating expenses in the slower seasons.

3 Types of Cash Flow

There are 3 areas of your business that impact cash flow: Operations, financing, and investments.

1. Cash Flow from Operating Activities

Your operating cash flow is the money moving into and out of your business related to your normal business operations.

Inflow example: money received from your clients

Outflow example: money paid to cover rent, utilities, travel, cell phone, and other expenses

2. Cash Flow from Financing Activities

Inflow example: cash received from a bank loan

Outflow example: monthly loan repayments

3. Cash Flow from Investing Activities

Buying or selling an investment results in negative or positive cash flow for your business. When calculating cash flow, purchasing or divesting physical assets like buildings, land and vehicles, are considered investing activities.

Inflow example: money received from selling investment funds or equipment

Outflow example: money paid to purchase investment funds or equipment

Related Articles

Cash Flow Statements: How to Calculate Cash Flow

You know what cash flow is. You know why it’s important. But how, exactly, do you determine your cash flow?

Calculating cash flow usually involves preparing a cash flow statement. Along with the income statement and the balance sheet, the cash flow statement is one of the most important financial statements for understanding your business.

While your balance sheet can show you much cash you have, cash flow statements show the details of how and where cash is coming into and out of your business (the cash inflows and cash outflows), during a specific time period.

You can create a cash flow statement for any timeframe, but most business owners generate the report monthly.

Cash flow statements are broken up into 3 sections that match the 3 types of cash flow covered earlier:

There are 2 ways to prepare a cash flow statement: The indirect and direct method.

1. The Indirect Method

It might sound counterintuitive, but the indirect method is actually the simpler way to prepare a cash flow statement—and, as such, is the one most commonly used.

When using the indirect method, you adjust your net income based on cash inflows and outflows to see how much cash you have available.

Example:

In that situation, your cash flow statement (using the indirect method) would look like this:

XYZ MARKETING AGENCY CASH FLOW STATEMENT – MARCH

On the cash flow statement, your ending cash flow balance is calculated by taking your net income and adding/subtracting your net cash from operations, investing, and financing.

2. The Direct Method

Often the go-to for larger businesses, the direct method takes a more detailed approach, listing all of your cash income and payments or expenses separately, line by line.

While this can give you deeper insights into exactly where your cash is coming from and where it’s going, it’s also a lot more time-consuming and labor-intensive to prepare. So unless you have a specific reason for going with the direct method, as a small business owner, the indirect method is likely your best bet.

Managing Cash Flow

Understanding cash flow is important. But in order to ensure that you have the cash you need to sustain your business, you need to do more than understand cash flow as a concept; you need to track your cash flow, dig into your numbers (also known as cash flow analysis), and figure out how and where you can make changes to push your business away from negative cash flows and towards positive cash flows.

This is called cash flow management, and it’s critical for keeping your business out of the red. Effective cash flow management has 2 key elements: Being on top of your invoices and your expenses.

Track Your Income

Part of cash flow analysis is knowing how much cash is coming into your business and when—and that means tracking your invoices.

When you send an invoice, it’s important to track when it was sent, when payment is due, when it’s actually paid, and your monthly invoice total. That way, you can get a fairly accurate estimate of how much cash will be flowing into your business each month.

Example:

Armed with that information, you can adjust your cash flow forecasting and plan for the deficit and ensure you have enough cash on hand to cover all of your expenses in the coming months. (Also, you may consider getting rid of that client.)

While you can track your invoices manually, using accounting software will automate the process, making it easier to track payments and manage cash flow.

Track Your Expenses

When you track your invoices, you’re aware of the cash flowing into your business—but it’s just as important to see the cash flowing out of your business, which means getting serious about tracking your expenses.

The more organized you are with tracking your expenses, the easier it will be to dig into your cash flows and use those insights to drive your strategy—so make sure to organize your expenses by category.

Example:

Again, you can track expenses manually, but the process will be easier, faster, and more streamlined with the right accounting software. (FreshBooks automatically categorizes expenses for you.)

Related Articles

4 Ways to Improve Your Cash Flow

The end goal of managing your cash flow is, of course, to improve it. But how, exactly, do you do that?

Here are 4 strategies to boost cash flow in your business—and ensure you have the cash on hand you need to move your business forward.

1. Increase Your Revenue

If you want to improve cash flow in your business, one of the best things you can do? Look for ways to make more money. In other words, increase your revenue.

This might mean selling more of your products or services, raising your prices, or increasing the frequency with which your customers purchase from you.

And as long as your strategies don’t also increase your operating expenses, you’ll see a boost in your net cash flow.

2. Lower Your Expenses

Bringing more money into your business is a solid strategy to improve cash flow. But taking steps to mitigate cash outflow is an equally worthy strategy.

Look for ways to lower your monthly expenses. While some expenses (like rent or utilities) are likely fixed, you may have wiggle room in other areas—like travel and entertainment, bank fees, or contractors.

If you can find ways to cut out expenses, it will help to boost your net cash flow—as long as you don’t spend that money elsewhere.

3. Get Invoices Paid Faster

Have you ever had a client pay an invoice late? If so, you’re not alone. According to Fundbox, 64% of small business owners face late payment problems. And while the occasional late payment may not be a major concern, if clients or customers chronically pay late, it can wreak havoc on your cash flow.

Luckily, there are steps you can take to increase the likelihood your invoices get paid on time, including:

4. Be Strategic With Your Invoicing

Sometimes, maintaining positive cash flow comes down to timing. So, if you want to improve cash flow in your business, you want to be strategic about managing when money is coming in versus when money is going out. Essentially, the better you align your payables and receivables, the better your cash flow.

Example:

Your marketing agency sends out client invoices on the 30th of every month. Clients have 30 days to pay their invoices. That means that you’ll generally get an influx of cash at the end of the month—so, if possible, you would want to align any major expenses (like debt repayment or big business purchases) to fall around the end of the month.

Don’t Let Cash Flow Kill Your Business

Cash flow is the lifeblood of your small business. Unfortunately, some small businesses don’t fully understand it until it’s too late, and they no longer have the cash to cover the bills.

Understanding the basics of cash flow—how it impacts your business, how to calculate it using a cash flow statement, and how to improve it—can make or break your business. Armed with this information, you can effectively plan for and anticipate the cash you need to keep your business moving forward.

This post was updated in March 2022.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/adam_hayes-5bfc262a46e0fb005118b414.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/AmyImage-AmyDrury-d6b6143c6d5c49a0add2201e25969457.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/jeanforthebalancecropped-5b7e9a58c9e77c0050e07fe1.jpg)

:strip_icc()/cash-flow-how-it-works-to-keep-your-business-afloat-398180-v3-5b734281c9e77c0057b67a4c.png)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/NatalyaYashinaProfessional-NatalyaYashina-60cea5f1ffb640d898aae0e9fe268b21.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/SuzannesHeadshot-3dcd99dc3f2e405e8bd37271894491ac.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/dotdash_Final_Understanding_the_Cash_Flow_Statement_Jul_2020-01-013298d8e8ac425cb2ccd753e04bf8b6.jpg)