What is criminal law

What is criminal law

criminal law

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

Read a brief summary of this topic

criminal law, the body of law that defines criminal offenses, regulates the apprehension, charging, and trial of suspected persons, and fixes penalties and modes of treatment applicable to convicted offenders.

Criminal law is only one of the devices by which organized societies protect the security of individual interests and ensure the survival of the group. There are, in addition, the standards of conduct instilled by family, school, and religion; the rules of the office and factory; the regulations of civil life enforced by ordinary police powers; and the sanctions available through tort actions. The distinction between criminal law and tort law is difficult to draw with real precision, but in general one may say that a tort is a private injury whereas a crime is conceived as an offense against the public, although the actual victim may be an individual.

This article treats the principles of criminal law. For treatment of the law of criminal procedure, see procedural law: Criminal procedure.

Principles of criminal law

The traditional approach to criminal law has been that a crime is an act that is morally wrong. The purpose of criminal sanctions was to make the offender give retribution for harm done and expiate his moral guilt; punishment was to be meted out in proportion to the guilt of the accused. In modern times more rationalistic and pragmatic views have predominated. Writers of the Enlightenment such as Cesare Beccaria in Italy, Montesquieu and Voltaire in France, Jeremy Bentham in Britain, and P.J.A. von Feuerbach in Germany considered the main purpose of criminal law to be the prevention of crime. With the development of the social sciences, there arose new concepts, such as those of the protection of the public and the reform of the offender. Such a purpose can be seen in the German criminal code of 1998, which admonished the courts that the “effects which the punishment will be expected to have on the perpetrator’s future life in society shall be considered.” In the United States a Model Penal Code proposed by the American Law Institute in 1962 states that an objective of criminal law should be “to give fair warning of the nature of the conduct declared to constitute an offense” and “to promote the correction and rehabilitation of offenders.” Since that time there has been renewed interest in the concept of general prevention, including both the deterrence of possible offenders and the stabilization and strengthening of social norms.

Common law and code law

Important differences exist between the criminal law of most English-speaking countries and that of other countries. The criminal law of England and the United States derives from the traditional English common law of crimes and has its origins in the judicial decisions embodied in reports of decided cases. England has consistently rejected all efforts toward comprehensive legislative codification of its criminal law; even now there is no statutory definition of murder in English law. Some Commonwealth countries, however, notably India, have enacted criminal codes that are based on the English common law of crimes.

The criminal law of the United States, derived from the English common law, has been adapted in some respects to American conditions. In the majority of the U.S. states, the common law of crimes has been repealed by legislation. The effect of such actions is that no person may be tried for any offense that is not specified in the statutory law of the state. But even in these states the common-law principles continue to exert influence, because the criminal statutes are often simply codifications of the common law, and their provisions are interpreted by reference to the common law. In the remaining states prosecutions for common-law offenses not specified in statutes do sometimes occur. In a few states and in the federal criminal code, the so-called penal, or criminal, codes are simply collections of individual provisions with little effort made to relate the parts to the whole or to define or implement any theory of control by penal measures.

In western Europe the criminal law of modern times has emerged from various codifications. By far the most important were the two Napoleonic codes, the Code d’instruction criminelle of 1808 and the Code pénal of 1810. The latter constituted the leading model for European criminal legislation throughout the first half of the 19th century, after which, although its influence in Europe waned, it continued to play an important role in the legislation of certain Latin American and Middle Eastern countries. The German codes of 1871 (penal code) and 1877 (procedure) provided the models for other European countries and have had significant influence in Japan and South Korea, although after World War II the U.S. laws of criminal procedure were the predominant influence in the latter countries. The Italian codes of 1930 represent one of the most technically developed legislative efforts in the modern period. English criminal law has strongly influenced the law of Israel and that of the English-speaking African states. French criminal law has predominated in the French-speaking African states. Italian criminal law and theory have been influential in Latin America.

Since the mid-20th century the movement for codification and law reform has made considerable progress everywhere. The American Law Institute’s Model Penal Code stimulated a thorough reexamination of both federal and state criminal law, and new codes were enacted in most of the states. England enacted several important reform laws (including those on theft, sexual offenses, and homicide), as well as modern legislation on imprisonment, probation, suspended sentences, and community service. Sweden enacted a new, strongly progressive penal code in 1962. In Germany a criminal code was adopted in 1998 following the reunification of East and West Germany. In 1975 a new criminal code came into force in Austria. New criminal codes were also published in Portugal (1982) and Brazil (1984). France enacted important reform laws in 1958, 1970, 1975, and 1982, as did Italy in 1981 and Spain in 1983. Other reforms have been under way in Finland, the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland, and Japan. The republics formerly under the control of the Soviet Union also have actively revised their criminal codes, including Hungary (1961), Bulgaria (1968), Uzbekistan (1994), Russia (1996), Poland (1997), Kazakhstan (1997), Ukraine (2001), and Romania (2004).

Comparisons between the systems of penal law developed in the western European countries, and those having their historical origins in the English common law must be stated cautiously. Substantial variations exist even among the nations that adhere generally to the Anglo-American system or to the law derived from the French, Italian, and German codes. In many respects, however, the similarities of the criminal law in all states are more important than the differences. Certain forms of behaviour are everywhere condemned by law. In matters of mitigation and justification, the continental law tends to be more explicit and articulate than the Anglo-American law, although modern legislation in countries adhering to the latter has reduced these differences. Contrasts can be drawn between the procedures of the two systems, yet even here there is a common effort to provide fair proceedings for the accused and protection for basic social interests.

Criminal Law

The term “criminal law” refers to the actual laws, statutes, and rules that define acts and conduct as crimes, and establishes punishments for each type of crime. Criminal acts are generally those seen by the government to threaten public welfare or safety, the severity of which categorizes various crimes as either misdemeanor or felony. To explore this concept, consider the following criminal law definition.

Definition of Criminal Law

Origin

Late 16th century

Criminal Law vs. Civil Law

While civil law cases involve disputes between individuals or entities in which the parties seek a resolution to a contractual or other civil issue, criminal law cases involve the prosecution of an individual for a criminal act. In a civil case, the lawsuit is brought by an individual or entity seeking monetary or other remuneration from another individual or entity. A criminal law case is initiated by a prosecutor. An individual or entity found legally accountable in a civil lawsuit may be ordered to pay money, give up property, or perform certain contractual obligations, but are not subject to imprisonment. A person convicted of a criminal offense, however, may be ordered to pay a fine, and may be incarcerated.

What is a Crime

A crime is defined as any act or omission that violates a law. While most criminal acts in the U.S. are defined in written statutes, which vary significantly from state to state, some common law crimes do exist. No act may be considered or prosecuted as a crime if it has not already been established as a crime by statute, or by common law.

While common law is sometimes used in reference to laws and ideals brought forward through time, often from colonial England, it more currently refers to the edicts and decisions made by judges in court proceedings, which set a standard by which to judge future similar cases.

Crime of Omission

Individuals are seen as owing two types of duty towards others. First, they are bound to act according to the law, not violating current statute or the laws of the time. Second, people have a moral duty to act in certain circumstances, such actions described by moral values and traditions, referred to as a “moral duty.”

An example of moral duty might occur when Sam sees that Brian is drowning in shallow water. There is no specific law or statute that requires Sam to jump in and save Brian, but a moral duty would certainly require Sam to do whatever he could to save Brian. Common law and certain modern statutes apply objective consideration to whether or not an individual would risk injury to his health or well-being by proactively intervening to prevent injury to another. In the event an individual or entity failed to act, with the knowledge that his failure to act would contribute to or cause injury to another, he could be found guilty of a crime of omission.

In the drowning example above, if Brian was drowning in water only a foot deep, or there was no floatation device that Sam could toss to Brian, or if Sam had his cell phone in his pocket that could be used to call 9-1-1, yet Sam took no action to aid Brian, he could be found liable for a crime of omission. On the other hand, there is absolutely no requirement that a person put himself in harm’s way to provide aid, so if Brian was drowning in raging flood waters, Sam would not be held liable for not jumping in.

Elements of a Criminal Act

To find someone guilty of a criminal act, the prosecution must generally prove two different elements of the particular situation: (1) that the act occurred, and (2) that the act was purposeful, or that the accused had a conscious intent to act.

An “overt act” is something a person does on purpose, knowingly, or recklessly that is against the law. An act is “purposeful” when the person has a conscious intent to engage in the act, or to bring about a certain result. A purposeful act is deliberate and voluntary, not the result of a mistake, or an act coerced by another person. An action is “reckless” when the perpetrator knows it carries an uncalled-for risk for harm to another, yet consciously disregards that risk.

The “intent” to commit a criminal act must take place before the act itself, though the two may occur as instantly as simultaneous thoughts. The courts may assume criminal intent from certain facts of the case which would lead any reasonable person to make the same assumption. For example, the intent to commit armed robbery may be assumed by the defendant’s possession of a mask and gun, as long as the items coincide in some way with the robbery or attempted robbery.

Additionally, criminal intent may be assumed by the fact that the person committed the crime. In other words, it may be assumed a person intended that the “natural and probable consequences” of his voluntary or purposeful act would lead to the actual result. For example, it may be assumed that the person intended to commit murder by the fact that he purposefully pointed a gun at the victim and pulled the trigger.

Criminal Law Procedure

Criminal law procedure refers to the process of charging, prosecuting, and assigning punishment for criminal offenses. The actual procedures for dealing with criminal matters vary by jurisdiction, and written procedures exist for local, state, and federal jurisdictions, all of which generally begin with formal criminal charges, and end with the acquittal or conviction, and sentencing if appropriate, of a defendant.

In all U.S. jurisdictions, criminal law procedure places the burden of proof squarely on the prosecution, requiring the prosecution to prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the defendant is guilty. This relieves the defendant of having to prove his innocence, and any doubt as to the defendant’s guilt on any charge is resolved in his favor. This concept is known as “the presumption of innocence.”

Criminal Law in Action

The world is filled with people committing acts considered criminal offenses. From writing checks on a closed bank account, to murder and mayhem, the variety of ways people seek to thwart the law and cause harm to others is astounding. Throughout the years, many criminal law cases have been so astonishing as to make headlines.

The Leopold and Loeb Trial

The 1924 kidnapping and murder of a 14-year old boy by Nathan Leopold, Jr. and Richard Loeb, both sons of wealthy families and students of the University of Chicago, shocked the nation.

Leopold and Loeb, described as having a strangely intense relationship, engaged in a fantasy-turned-reality of committing the perfect crime. After much plotting and planning, the duo kidnapped 14-year old Bobby Franks as he walked home from school one day, killing him by striking him in the head with a chisel. They then drove to a nearby marshland, poured hydrochloric acid over Franks’ naked body, then stuffed it in a drainage culvert.

Leopold and Loeb’s now-famous attorney, Thomas Darrow, plead the boys guilty, then a month-long hearing ensued on the issue of whether they should face the death penalty. On August 22, 1924, Darrow presented a more than 12-hour argument in a jam-packed courtroom, attempting to convince the judge that he should take into consideration the boys’ youth, surging sexual urges, and even genetics that may have led to the commission of such a heinous crime.

Darrow’s efforts were met with derision as the prosecutor attacked his attempt to blame the crime on anything other than the defendants’ choice and intent. The judge, when announcing his decision, called the murder of Bobby Franks “a crime of singular atrocity,” for which “judgment cannot be affected” by the potential influences over the boys’ decisions. The judge’s sentence did, however, reflect consideration for the defendants’ young age, as well as the potential benefits to society and the science of criminology in the study of these two individuals. As a result, Leopold and Loeb were sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

The Trial of Bernhard Goetz

As the incident was publicized, frightened citizens quickly hailed Goetz as a hero, dubbing him the “subway vigilante.” Goetz was eventually indicted by a grand jury on three charges of illegal possession of a weapon, though the grand jury initially refused to indict him on charges of attempted murder or reckless endangerment. The prosecutor took the matter to a second grand jury, eventually securing the desired attempted murder charges.

During the trial, the prosecutor attempted to paint Goetz as a racist man with a “twisted and self-righteous sense of right and wrong.” He stated Goetz had shot one of the teens in the back while he was running away, and shot another point blank while he was sitting down on a subway seat, severing the youth’s spinal cord. The jury didn’t buy that the teens were “doing absolutely nothing to threaten or menace” Goetz, and were innocent victims.

Goetz’s attorney, Barry Slotnick, pointed out that Goetz was not “Rambo,” but rather a person surrounded by young men threatening him, who took the appropriate action to defend himself from “hoodlums” and “thugs.” Slotnick pointed out that the young men took on an assumption of risk that a citizen whom they were threatening, and who had no avenue of escape in an enclosed subway car, would take the lawful and justifiable action of firing a weapon in self defense.

The jury decided immediately to find Goetz guilty of illegally possessing a loaded firearm, as there was no question he possessed the gun on the subway and had no license to carry it. From there deliberations turned to the issue of intent. In the end, the jurors acquitted Goetz on the four charges of attempted murder, stating that, while he clearly desired to end the threat, whether it was real or imagined, he had no motivation to kill the teens. One of the jurors was quoted as saying that, whether Goetz’s feeling of being trapped was reasonable or not, “he didn’t go out hunting.”

Criminal Law Attorney

Criminal law

|

| Law Articles |

|---|

| Jurisprudence |

| Law and legal systems |

| Legal profession |

| Types of Law |

| Administrative law |

| Antitrust law |

| Aviation law |

| Blue law |

| Business law |

| Civil law |

| Common law |

| Comparative law |

| Conflict of laws |

| Constitutional law |

| Contract law |

| Criminal law |

| Environmental law |

| Family law |

| Intellectual property law |

| International criminal law |

| International law |

| Labor law |

| Maritime law |

| Military law |

| Obscenity law |

| Procedural law |

| Property law |

| Tax law |

| Tort law |

| Trust law |

The term criminal law, sometimes called penal law, refers to any of various bodies of rules in different jurisdictions whose common characteristic is the potential for unique and often severe impositions as punishment for failure to comply. Criminal law typically is enforced by the government, unlike the civil law, which may be enforced by private parties.

Contents

Criminal punishment, depending on the offense and jurisdiction, may include execution, loss of liberty, government supervision (parole or probation), or fines. There are some archetypal crimes, like murder, that feature in all such bodies of law, but the acts that are forbidden are not wholly consistent between different criminal codes, and even within a particular code lines may be blurred as civil infractions may give rise also to criminal consequences. Criminal law generally, thus, may be considered the rules that apply when an offense is committed against the public, society in general. In this sense, criminal law is of the utmost importance in maintaining and developing societies of peace and harmony, wherein all members contribute to the common good or must face the consequences.

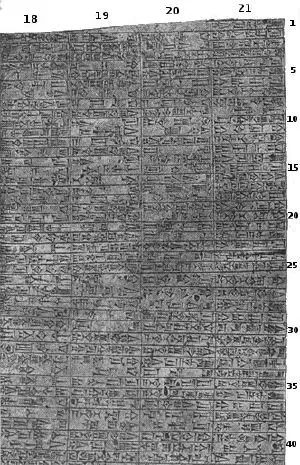

Criminal law history

The first civilizations generally did not distinguish between civil and criminal law. The first known written codes of law were produced by the Sumerians. In the twenty-first century B.C.E., King Ur-Nammu acted as the first legislator and created a formal system in 32 articles: the Code of Ur-Nammu. [1] Another important ancient code was the Code of Hammurabi, which formed the core of Babylonian law. Neither set of laws separated penal codes and civil laws.

The similarly significant Commentaries of Gaius on the Twelve Tables also conflated the civil and criminal aspects, treating theft or furtum as a tort. Assault and violent robbery were analogized to trespass as to property. Breach of such laws created an obligation of law or vinculum juris discharged by payment of monetary compensation or damages.

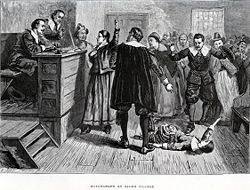

The first signs of the modern distinction between crimes and civil matters emerged during the Norman Invasion of England. [2] The special notion of criminal penalty, at least concerning Europe, arose in Spanish Late Scholasticism (see Alfonso de Castro, when the theological notion of God’s penalty (poena aeterna) that was inflicted solely for a guilty mind, became transfused into canon law first and, finally, to secular criminal law. [3] The development of the state dispensing justice in a court clearly emerged in the eighteenth century when European countries began maintaining police services. From this point, criminal law had formal the mechanisms for enforcement, which allowed for its development as a discernible entity.

Criminal law sanctions

Criminal law is distinctive for the uniquely serious potential consequences of failure to abide by its rules. Capital punishment may be imposed in some jurisdictions for the most serious crimes. Physical or corporal punishment may be imposed such as whipping or caning, although these punishments are prohibited in much of the world. Individuals may be incarcerated in prison or jail in a variety of conditions depending on the jurisdiction. Confinement may be solitary. Length of incarceration may vary from a day to life. Government supervision may be imposed, including house arrest, and convicts may be required to conform to particularized guidelines as part of a parole or probation regimen. Fines also may be imposed, seizing money or property from a person convicted of a crime.

Five objectives are widely accepted for enforcement of the criminal law by punishments: retribution, deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation and restitution. Jurisdictions differ on the value to be placed on each.

Criminal law jurisdictions

World except the United States, Yemen, Libya, and Iraq

Public international law deals extensively and increasingly with criminal conduct, that is heinous and ghastly enough to affect entire societies and regions. The formative source of modern international criminal law was the Nuremberg trials following the Second World War in which the leaders of Nazism were prosecuted for their part in genocide and atrocities across Europe. In 1998 an International criminal court was established in the Hague under what is known as the Rome Statute. This is specifically to try heads and members of governments who have taken part in crimes against humanity. Not all countries have agreed to take part, including Yemen, Libya, Iraq and the United States.

United States

In the United States, criminal prosecutions typically are initiated by complaint issued by a judge or by indictment issued by a grand jury. As to felonies in Federal court, the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution requires indictment. The Federal requirement does not apply to the states, which have a diversity of practices. Three states (Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Washington) and the District of Columbia do not use grand jury indictments at all. The Sixth Amendment guarantees a criminal defendant the right to a speedy and public trial, in both state and Federal courts, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime was committed, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of Counsel for his defense. The interests of the state are represented by a prosecuting attorney. The defendant may defend himself pro se, and may act as his own attorney, if desired.

In most U.S. law schools, the basic course in criminal law is based upon the Model Penal Code and examination of Anglo-American common law. Crimes in the U.S. which are outlawed nearly universally, such as murder and rape are occasionally referred to as malum in se, while other crimes reflecting society’s social attitudes and morality, such as laws prohibiting use of marijuana are referred to as malum prohibitum.

United Kingdom

Criminal law in the United Kingdom derives from a number of diverse sources. The definitions of the different acts that constitute criminal offenses can be found in the common law (murder, manslaughter, conspiracy to defraud) as well as in thousands of independent and disparate statutes and more recently from supranational legal regimes such as the European Union. As the law lacks the criminal codes that have been instituted in the United States and civil law jurisdictions, there is no unifying thread to how crimes are defined, although there have been calls from the Law Commission for the situation to be remedied. Criminal trials are administered hierarchically, from magistrates’ courts, through the Crown Courts and up to the High Court. Appeals are then made to the Court of Appeal and finally the House of Lords on matters of law.

Procedurally, offenses are classified as indictable and summary offenses; summary offenses may be tried before a magistrate without a jury, while indictable offenses are tried in a crown court before a jury. The distinction between the two is broadly between that of minor and serious offenses. At common law crimes are classified as either treason, felony or misdemeanor.

The way in which the criminal law is defined and understood in the United Kingdom is less exact than in the United States as there have been few official articulations on the subject. The body of criminal law is considerably more disorganized, thus finding any common thread to the law is very difficult. A consolidated English Criminal Code was drafted by the Law Commission in 1989 but, though codification has been debated since 1818, as of 2007 had not been implemented.

Selected Criminal Laws

Many laws are enforced by threat of criminal punishment, and their particulars may vary widely from place to place. The entire universe of criminal law is too vast to intelligently catalog. Nevertheless, the following are some of the more known aspects of the criminal law.

Elements

The criminal law generally prohibits undesirable acts. Thus, proof of a crime requires proof of some act. Scholars label this the requirement of an actus reus or guilty act. Some crimes — particularly modern regulatory offenses — require no more, and they are known as strict liability offenses. Nevertheless, because of the potentially severe consequences of criminal conviction, judges at common law also sought proof of an intent to do some bad thing, the mens rea or guilty mind. As to crimes of which both actus reus and mens rea are requirements, judges have concluded that the elements must be present at precisely the same moment and it is not enough that they occurred sequentially at different times. [4]

Actus reus

Actus reus is Latin for «guilty act» and is the physical element of committing a crime. It may be accomplished by an action, by threat of action, or exceptionally, by an omission to act. For example, the act of A striking B might suffice, or a parent’s failure to give food to a young child also may provide the actus reus for a crime.

Where the actus reus is a failure to act, there must be a duty. A duty can arise through contract, [5] a voluntary undertaking, [6] a blood relation with whom one lives, [7] and occasionally through one’s official position. [8] Duty also can arise from one’s own creation of a dangerous situation. [9] Occasional sources of duties for bystanders to accidents in Europe and North America are good samaritan laws, which can criminalize failure to help someone in distress (such as a drowning child).

An actus reus may be nullified by an absence of causation. For example, a crime involves harm to a person, the person’s action must be the but for cause and proximate cause of the harm. [10] If more than one cause exists (such as harm comes at the hands of more than one culprit) the act must have «more than a slight or trifling link» to the harm. [11]

Causation is not broken simply because a victim is particularly vulnerable. This is known as the thin skull rule. [12] However, it may be broken by an intervening act (novus actus interveniens) of a third party, the victim’s own conduct, [13] or another unpredictable event. A mistake in medical treatment typically will not sever the chain, unless the mistakes are in themselves «so potent in causing death.» [14]

Mens rea

Mens rea is the Latin phrase meaning «guilty mind.» A guilty mind means an intention to commit some wrongful act. Intention under criminal law is separate from a person’s motive. If Robin Hood robs from rich Sheriff Nottingham because his motive is to give the money to poor Maid Marion, his «good intentions» do not change his criminal intention to commit robbery. [15]

A lower threshold of mens rea is satisfied when a defendant recognises an act is dangerous but decides to commit it anyway. This is recklessness. For instance, if C tears a gas meter from a wall to get the money inside, and knows this will let flammable gas escape into a neighbor’s house, he could be liable for poisoning. Courts often consider whether the actor did recognize the danger, or alternatively ought to have recognized a risk. [16] Of course, a requirement only that one ought to have recognized a danger (though he did not) is tantamount to erasing intent as a requirement. In this way, the importance of mens rea has been reduced in some areas of the criminal law.

Wrongfulness of intent also may vary the seriousness of an offense. A killing committed with specific intent to kill or with conscious recognition that death or serious bodily harm will result, would be murder, whereas a killing effected by reckless acts lacking such a consciousness could be manslaughter. [17] On the other hand, it matters not who is actually harmed through a defendant’s actions. The doctrine of transferred malice means, for instance, that if a man intends to strike a person with his belt, but the belt bounces off and hits another, mens rea is transferred from the intended target to the person who actually was struck. [18] ; though for an entirely different offense, such as breaking a window, one cannot transfer malice. [19]

Strict liability

Not all crimes require bad intent, and alternatively, the threshold of culpability required may be reduced. For example, it might be sufficient to show that a defendant acted negligently, rather than intentionally or recklessly. In offenses of absolute liability, other than the prohibited act, it may not be necessary to show anything at all, even if the defendant would not normally be perceived to be at fault. Most strict liability offenses are created by statute, and often they are the result of ambiguous drafting unless legislation explicitly names an offense as one of strict liability.

Fatal offenses

A murder, defined broadly, is an unlawful killing or homicide. Unlawful killing is probably the act most frequently targeted by the criminal law. In many jurisdictions, the crime of murder is divided into various gradations of severity, such as murder in the first degree, based on intent. Malice is a required element of murder. Manslaughter is a lesser variety of killing committed in the absence of malice, brought about by reasonable provocation, or diminished capacity. Involuntary manslaughter, where it is recognized, is a killing that lacks all but the most attenuated guilty intent, recklessness.

Personal offenses

Many criminal codes protect the physical integrity of the body. The crime of battery is traditionally understood as an unlawful touching, although this does not include everyday knocks and jolts to which people silently consent as the result of presence in a crowd. Creating a fear of imminent battery is an assault, and also may give rise to criminal liability. Non-consensual intercourse, or rape, is a particularly egregious form of battery.

Property offenses

Property often is protected by the criminal law. Trespassing is unlawful entry onto the real property of another. Many criminal codes provide penalties for conversion, embezzlement, theft, all of which involve deprivations of the value of property. Robbery is a theft by force.

Participatory offenses

Some criminal codes criminalize association with a criminal venture or involvement in criminality that does not actually come to fruition. Some examples are aiding, abetting, conspiracy, and attempt.

Defenses

There are a variety of conditions that will tend to negate elements of a crime (particularly the intent element) that are known as defenses. The label may be apt in jurisdictions where the accused may be assigned some burden before a tribunal. However, in many jurisdictions, the entire burden to prove a crime is on the government, which also must prove the absence of these defenses, where implicated. In other words, in many jurisdictions the absence of these so-called defenses is treated as an element of the crime. So-called defenses may provide partial or total refuge from punishment.

Insanity

Insanity or mental disorder (Australia and Canada), may negate the intent of any crime, although it pertains only to those crimes having an intent element. A variety of rules have been advanced to define what, precisely, constitutes criminal insanity. The most common definitions involve either an actor’s lack of understanding of the wrongfulness of the offending conduct, or the actor’s inability to conform conduct to the law. [20] If one succeeds in being declared «not guilty by reason of insanity,» then the result frequently is treatment mental hospital, although some jurisdictions provide the sentencing authority with flexibility. [21]

Automatism

Automatism is a state where the muscles act without any control by the mind, or with a lack of consciousness. [22] One may suddenly fall ill, into a dream like state as a result of post traumatic stress, [23] or even be «attacked by a swarm of bees» and go into an automatic spell. [24] However to be classed as an «automaton» means there must have been a total destruction of voluntary control, which does not include a partial loss of consciousness as the result of driving for too long. [25] Where the onset of loss of bodily control was blameworthy, for example the result of voluntary drug use, it may be a defense only to specific intent crimes.

Intoxication

In some jurisdictions, intoxication may negate specific intent, a particular kind of mens rea applicable only to some crimes. For example, lack of specific intent might reduce murder to manslaughter. Voluntary intoxication nevertheless often will provide basic intent, for example the intent required for manslaughter. [26] On the other hand, involuntary intoxication, for example when another put alcohol in what the person believed to be a non-alcoholic drink, without their knowledge, may give rise to no inference of basic intent.

Mistake

«I made a mistake» is a defense in some jurisdictions if the mistake is about a fact and is genuine. For example, a charge of battery on a police officer may be negated by genuine (and perhaps reasonable) mistake of fact that the person battered was a criminal and not an officer. [27]

Self defense

Self-defense is, in general, some reasonable action taken in protection of self. An act taken in self-defense often is not a crime at all; no punishment will be imposed. To qualify, any defensive force must be proportionate to the threat. Use of a firearm in response to a non-lethal threat is a typical example of disproportionate force.

Duress

One who is «under duress» is forced into an unlawful act. Duress can be a defense in many jurisdictions, although not for the most serious crimes of murder, attempted murder, being an accessory to murder [28] and in many countries, treason. [29] The duress must involve the threat of imminent peril of death or serious injury, operating on the defendant’s mind and overbearing his will. Threats to third persons may qualify. [30] The defendant must reasonably believe the threat, [31] and there is no defense if «a sober person of reasonable firmness, sharing the characteristics of the accused» would have responded differently. [32] Age, pregnancy, physical disability, mental illness, sexuality have been considered, although basic intelligence has been rejected as a criterion. [33]

The accused must not have foregone some safe avenue of escape. [34] The duress must have been an order to do something specific, so that one cannot be threatened with harm to repay money and then choose to rob a bank to repay it. [35] If one puts himself in a position where he could be threatened, duress may not be a viable defense.

Criminal law and society

Criminal law distinguishes crimes from civil wrongs such as tort or breach of contract. Criminal law has been seen as a system of regulating the behavior of individuals and groups in relation to societal norms, whereas civil law is aimed primarily at the relationship between private individuals and their rights and obligations under the law.

However, many ancient legal systems did not clearly define a distinction between criminal and civil law, and in England there was little difference until the codification of criminal law occurred in the late nineteenth century. In most U.S. law schools, the basic course in criminal law is based upon the English common criminal law of 1750 (with some minor American modifications like the clarification of mens rea in the Model Penal Code).

Notes

References

External links

All links retrieved April 30, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Criminal Law

What Is Criminal Law?

In the United States, there are two types of laws meant to punish wrongdoing or compensate victims of bad acts. These are known as civil law and criminal law. Civil law is meant to deal with behavior that causes some sort of injury to an individual or other private party through lawsuits. The repercussions for any parties found liable for these acts are usually monetary, but can also include court-ordered remedies like injunctions or restraining orders.

Criminal law, on the other hand, is designed to deal with behavior that is considered an offense against society, the state, or public, even if the victim is an individual person. Not only can someone convicted of a crime be forced to pay fines, but they can also lose their freedom by being sentenced to jail or prison time.

But no matter if someone is being charged with a serious crime or a minor, the accused person still has the right to a trial, as well as certain other legal protections. Here is a short guide to how the criminal law system functions.

What Is Criminal Procedure?

Criminal procedure refers to the overall legal process of adjudicating claims for a person who is accused of violating criminal laws. The main idea behind all criminal procedures is known as the “presumption of innocence,” meaning that a suspect is innocent until proven guilty.

Criminal procedure includes matters such as:

There are numerous criminal justice careers an individual can choose to engage in, including:

How Does Criminal Law Procedure Work?

There are only two bodies that can bring a criminal case against someone, the federal government or a state government. This is why you see cases stylized as US v. Someone or State v. Someone. Whether the accused is charged in federal court or in a state court depends on what crime they are being charged with and where the alleged offense occurred. Every state has their own set of criminal laws, but there are certain Constitutional rights that apply to every defendant, no matter what that crime is or where it happened.

These include:

If an individual believes their rights have been violated due to police misconduct, they should contact a lawyer as soon as possible.

What Happens During a Criminal Trial?

Because every jurisdiction has their own procedural rules, the steps and timing of a criminal trial vary widely. But all trials are generally broken into two phases: the guilt phase and the sentencing phase. During the guilt phase, the prosecutor and the defense present elements to prove that the defendant’s behavior has or has not met all the elements of that particular criminal charge.

The prosecutor must show beyond a reasonable doubt (the highest burden of proof in American law) that the person committed the actus reus (criminal activity) with the proper mens rea (mental state or intent required by the charge). If the jury/judge finds that all these elements have been met, they can then declare the defendant guilty.

The next phase is known as the sentencing phase. As the name suggests, during the sentencing phase the judge/jury looks at state or federal law dictating the punishment range for the crime or crimes the defendant was convicted of. They look at many different factors like previous criminal history, aggravating and mitigating factors, and other pertinent facts to determine the person’s punishment. Only once both phases are completed will a convicted individual officially receive their punishment, such as fines, prison time, or both.

What Kinds of Crimes Can Someone Be Convicted Of?

Criminal acts are classified from less serious petty offenses like simple theft to the most serious offenses like drug trafficking and murder. Every jurisdiction and the federal courts have different ways to classify these crimes, from misdemeanors and disorderly conduct charges to felonies.

The term misdemeanor may include a very wide range of criminal offenses and violations, including:

The following is a general list of felony crimes:

It is also important to note that there are certain offenses which may be charged as felonies or misdemeanors, depending on the laws of the state as well as the circumstances of the offense. These may include:

Some of these offenses may be eligible for expungement, or removal from an individual’s criminal record. The requirements and processes for expungement vary by jurisdiction, so it may be helpful to consult with an attorney for advice regarding how to have a conviction expunged.

There are also certain offenses, such as speeding and moving violations that are considered infractions. These violations only affect an individual’s driving record, not their criminal record.

There is also a separate category for juvenile crimes, which are crimes that are committed by minors. These crimes are adjudicated in a separate system, the juvenile justice system.

The type of crime someone can be charged with depends on where the crime occurred. There can be some confusion, though, over whether the offense will be charged under state law or federal law. The best way to understand the difference is to seek the help of a criminal defense attorney in your area that specializes in both state and federal criminal law.

Criminal laws can vary widely by state. For instance, criminal laws in South Dakota or North Dakota can actually differ drastically from those in other regions like Montana.

Metropolitan areas such as those in Los Angeles, Atlanta, or Northern New Jersey may have a mix of criminal activity occurring. Other states may have unique criminal statutes which may seem unusual to us. For example, Massachusetts criminal law outlaws dueling and has two types of assault and battery with one relating to general assault and battery and one that is due to debt collecting.

These laws are rather specific and may not be found in other parts of the country, so it is important to check your local laws to find out if your criminal actions fall under a specific statute.

Do I Need an Attorney for a Criminal Law Issue?

All areas of the law can be complicated, but when someone is facing criminal charges the situation can quickly become confusing. Depending on the charges, receiving a criminal conviction can carry very serious consequences for the accused, including a permanent criminal record and loss of freedom.

An experienced criminal defense attorney’s job is to make sure you know all your rights, that they are being protected, and will know the best strategies to help you get the best outcome possible in your case. Remember, with criminal charges, access to a criminal defense attorney is your right.

Criminal law is designed to address and punish behavior that is considered to be an offense against society, the state, or public. This remains true even if the victim is an individual person. If a person is convicted of a crime, they may be forced to pay fines and may…

What is Criminal Law?

Criminal law is the area of law that relates to prohibited conduct in society. When government leaders take steps to ban certain actions, they create crimes. Criminal law is the area of law that involves enforcing criminal law as well as defending against allegations of violations of criminal law.

The purpose of outlawing conduct is to protect society. Law makers typically pass a law with the belief that it’s for the public good. Criminal laws must be applied evenly to everyone. Lawmakers can’t make a law that targets only one person. The purposes of punishing criminal offenders include retribution, deterring certain behaviors, preventing additional offenses and rehabilitation of offenders.

What makes a law a crime?

An act isn’t a crime just because government officials prohibit the behavior. Instead, a behavior is a crime because of the penalties that are attached to a violation. In the case of a crime, a person’s freedom is usually on the line.

Each crime carries a maximum penalty. That penalty is the most amount of time that a person can spend in jail if they’re convicted of the offense. A criminal offense often has other penalties such as a fine, probation and placing a record of the offense on a person’s public, criminal history. However, the distinguishing characteristic of criminal law is that a person who commits a criminal offense might spend time in jail or prison.

Felony and misdemeanor offenses

Crimes are classified as felony offenses and misdemeanor offenses. Typically, a crime is a felony if the maximum possible penalty is more than one year in jail. A felony usually brings the possibility of going to a state prison rather than a local jail. A misdemeanor is a crime that carries a maximum penalty of less than one year in jail.

Some states have low-level misdemeanors that don’t carry the possibility of jail time. For example, in Michigan, a minor who drives with a blood alcohol content is guilty of a misdemeanor that’s punishable by only a fine and community service. Each state may have unique classifications for a few types of offenses. For example, for certain felony offenses in Texas, offenders face only the possibility of confinement in a state jail for not less than 180 days or more than two years.

Federal, state and local crimes

In the United States, all levels of government can create crimes. The federal government, state governments and even local authorities can create crimes. It’s also up to the unit of government that creates the law to enforce it. If you’re charged with a federal crime, you answer to it in federal court. If a local unit of government charges someone with a crime, they have to file the paperwork in the appropriate court and bring their own attorney to pursue prosecution of the offense.

A smaller unit of government can’t invalidate a higher unit’s law

A state or local law can be more restrictive than a federal law, but a state or local government cannot invalidate a federal law. For example, if the state government makes it illegal to possess marijuana, a city government can’t come along and invalidate that law. While the city can make a policy that says their law enforcement officers aren’t going to enforce the law, they can’t nullify a state or federal law.

Stages in a criminal law case

A criminal case starts with an arrest or the filing of formal charges. Ultimately, it’s up to an attorney for the government to decide to charge a person with a crime. While the police can make an initial arrest, a person doesn’t formally face charges until the state’s attorney files them.

An arraignment is the first court appearance. A judge or magistrate formally reads the accused person the details of the charges they’re facing. They set a bond amount and conditions of bond. In rare and serious cases, they may order law enforcement to hold the person without bond until resolution of the case.

The defense has time and power to gather information about the case. The defense can serve a discovery demand that requires the state’s attorney to produce evidence about the case. The state’s attorney always has an ethical obligation to provide the defense with evidence that might be favorable to their defense.

If the parties reach a resolution, the case may not go to trial. The state might agree to dismiss the charges, they might agree to dismiss the charges with conditions, or they might reach a plea resolution. If the parties can’t resolve the case, a judge or jury may hear the evidence at a formal trial. If the jury finds the defendant not guilty, the case ends. If they find the defendant guilty, the case proceeds to sentencing.

What does a criminal lawyer do?

Advises clients about the potential consequences of a course of action

A criminal lawyer helps their client understand criminal laws. They also help the client understand how their actions may or may not violate a criminal law. A defense attorney might help their client understand whether a proposed course of action is a crime. An attorney for the state might help law enforcement officers understand best practices for enforcing the law.

Helps their client present their case or present a defense

A prosecutor or district attorney presents evidence and pursues prosecution of cases on behalf of the unit of government that they represent. They make decisions about whether to extend a plea offer. They present the evidence on behalf of the state at trial.

A defense attorney helps their client present a defense. A defense attorney gathers evidence for their client. They evaluate the case in order to determine viable defenses. If they need to file pretrial motions, they make sure they file the motions in the right way.

Protects their client’s constitutional rights

Citizens have constitutional rights. No unit of government can pass a law that violates a person’s right to be free from an unreasonable search and seizure. Law enforcement also can’t keep a person in jail for an indefinite period of time. Criminal attorneys must know how the constitution and criminal law intersect. They must be aware of constitutional implications of law as they go about their work and advocate for their clients as necessary in order to protect and defend their constitutional rights.

Why practice criminal law

A criminal law practice requires diverse skills and a capacity for memorization. It’s also exciting. For lawyers who like frequent court appearances and the occasional appearance on television, criminal law is a good fit. Criminal lawyers must be comfortable in high pressure situations. They also must be able to think on their feet. There often isn’t time to look something up or seek a second opinion when they must act in a matter of seconds to move to admit evidence or make an objection.

Criminal law is a good fit for lawyers who don’t like to sit still. Lawyers who choose to focus on state laws in a small geographic region can expect to have multiple court hearings a week. They can expect to conduct trials and other contested hearings.

Lawyers who focus on crime also have the academic challenge of building a case. They review police reports and interview witnesses. They examine possible defenses and determine whether or not they apply to the case. Being an effective criminal lawyer requires a well rounded mix of academic skills and oral advocacy. Criminal lawyers also benefit from having a high capacity for rote memorization.

Writing and speaking

Criminal lawyers can’t rely on speaking or writing alone. A criminal lawyer must write clearly in order to properly file motions and help the court understand nuanced issues of law. They must also have the trial advocacy skills to conduct complex trials. Whether a lawyer advocates on behalf of the state or for an accused, they must also have the interpersonal skills to interact with the other side and the jury.

Why Become a Criminal Lawyer – Making crime into a career

Crime and punishment is serious business. Society depends on state prosecutors and district attorneys to advocate for the safety of the public. At the same time, defendants rely on their attorneys to protect their rights and advocate on their behalf. That makes criminal law a high stakes affair.

For attorneys who enjoy writing and the courtroom, criminal law is an option to explore. Criminal attorneys spend time investigating and using logic to evaluate their case and prepare a defense. They file motions and other paperwork and argue cases in court. For attorneys who love thinking on their feet, criminal law is a worthy career choice.