What is science fiction

What is science fiction

Science Fiction

I. What is Science Fiction?

Science fiction, often called “sci-fi,” is a genre of fiction literature whose content is imaginative, but based in science. It relies heavily on scientific facts, theories, and principles as support for its settings, characters, themes, and plot-lines, which is what makes it different from fantasy.

So, while the storylines and elements of science fiction stories are imaginary, they are usually possible according to science—or at least plausible.

Although examples of science fiction can be found as far back as the Middle Ages, its presence in literature was not particularly significant until the late 1800s. Its true popularity for both writers and audiences came with the rise of technology over the past 150 years, with developments such as electricity, space exploration, medical advances, industrial growth, and so on. As science and technology progress, so does the genre of science fiction.

II. Example of Science Fiction

Read the following short passage:

As the young girl opened her window, she could see the moons Europa and Callipso rising in the distance. A comet flashed by, followed by a trail of stardust, illuminating the dark, endless space that surrounded the spacecraft; the only place she had ever known as home. As she gazed at Jupiter, she dreamed of a life where she wasn’t stuck orbiting a planet, but living on one. She envisioned stepping onto land, real land, like in the stories of Earth her father had told her about. She tried to imagine the taste of fresh air, the feel of a cool, salty ocean, and the sound of wind rustling through a tree’s green leaves. But these were only fantasies, not memories. She had been born on the ship, and if they didn’t find a new inhabitable planet soon, she would surely die there too.

The example above has several prime characteristics that are common in science fiction. First, it is set in the future, when humans no longer live on Earth. Second, it takes place on a spacecraft that is orbiting Jupiter. Third, it features real scientific information—Europa and Callipso are two of Jupiter’s moons, and as Jupiter is a planet made of gas, it would not be possible for humans to live there, explaining why the ship is currently orbiting the planet rather than landing on it.

III. Types of Science Fiction

Science fiction is usually distinguished as either “hard” or “soft.”

Hard science fiction

Hard science fiction strictly follows scientific facts and principles. It is strongly focused on natural sciences like physics, astronomy, chemistry, astrophysics, etc. Interestingly, hard science fiction is often written by real scientists, and has been known for making both accurate and inaccurate predictions of future events. For example, the recent film Gravity, the story of an astronaut whose spacecraft is damaged while she repairs a satellite, was renowned for its scientific accuracy in terms of what would actually happen in space.

Soft science fiction

Soft science fiction is characterized by a focus on social sciences, like anthropology, sociology, psychology, politics—in other words, sciences involving human behavior. So, soft sci-fi stories mainly address the possible scientific consequences of human behavior. For example, the Disney animated film Wall-E is an apocalyptic science fiction story about the end of life on Earth as a result of man’s disregard for nature.

In truth, most works use a combination of both hard and soft science fiction. Soft sci-fi allows audiences to connect on an emotional level, and hard sci-fi adds real scientific evidence so that they can imagine the action actually happening. So, combining the two is a better storytelling technique, because it lets audiences connect with the story on two levels. Science fiction also has a seemingly endless number of subgenres, including but not limited to time travel, apocalyptic, utopian/dystopian, alternate history, space opera, and military science fiction.

IV. Importance of Science Fiction

Many times, science fiction turns real scientific theories into full stories about what is possible and/or imaginable. Many stories use hard facts and truths of sciences to:

Historically it has been a popular form for not only authors, but scientists as well. In the past 150 years, science fiction has become a huge genre, with a particularly large presence in film and television—in fact, the TV network “SciFi” is completely devoted to science fiction media. It is a particularly fascinating and mind-bending genre for audiences because of its connection to reality.

V. Examples of Science Fiction in Literature

Example 1

A genre-defining piece of science fiction literature is H.G. Wells’ 1898 novel The War of the Worlds, which tells the story of an alien invasion in the United Kingdom that threatens to destroy mankind. The following is a selection from the novel’s introduction:

No one would have believed in the last years of the nineteenth century that this world was being watched keenly and closely by intelligences greater than man’s and yet as mortal as his own; that as men busied themselves about their various concerns they were scrutinized and studied, perhaps almost as narrowly as a man with a microscope might scrutinize the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water. With infinite complacency men went to and fro over this globe about their little affairs, serene in their assurance of their empire over matter…No one gave a thought to the older worlds of space as sources of human danger.

Here, the narrator describes a time when mankind was naive. He is setting up for the story of when Earth was unexpectedly attacked by an alien race, and how they were completely unprepared and too proud to believe that any other force in the universe could threaten them. Though only a story, War of the Worlds addressed a scientific concern and possibility that is a mystery for mankind.

Example 2

Published in 1949, George Orwell’s 1984 shows the future of mankind in a dystopian state. It is set in what is now the United Kingdom, and shows society under tyrannical rule of a government that has their population under constant surveillance and threat of imprisonment for having wrong thoughts. Throughout the novel is the constant theme that “Big Brother” is watching.

Outside, even through the shut window-pane, the world looked cold. Down in

the street little eddies of wind were whirling dust and torn paper into

spirals, and though the sun was shining and the sky a harsh blue, there

seemed to be no color in anything, except the posters that were plastered

everywhere. The black-moustachio’d face gazed down from every commanding

corner. There was one on the house-front immediately opposite. BIG BROTHER

IS WATCHING YOU, the caption said, while the dark eyes looked deep into

Winston’s own.

This passage describes the story’s setting—dull, colorless, and monitored—and hints at society’s status. At the beginning, Winston is a citizen who wants to fight the system, but by the end, he falls victim to the government’s control tactics.

VI. Examples of Science Fiction in Pop Culture

Example 1

Perhaps the most popular and well-known examples of science fiction in popular culture—specifically “space opera” science fiction—are George Lucas’s legendary Star Wars films. Star Wars has perhaps one of the largest (if not the largest) fan-followings of all time; and its status in the science fiction world is absolutely epic. This renowned science fiction series is particularly unique because it actually starts in the middle of the story, with “Episode IV.” In fact, Episodes I, II, and III weren’t produced until almost 40 years after the first film’s debut. The following clip captures the well-known opening of the first film, Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope, which is now referred to as the “Star Wars Opening Crawl.” It also features the iconic “Star Wars Theme Song,” which is instantly recognizable by fans and non-fans alike.

Science Fiction

Science fiction (also, sf, SF, or sci-fi) is a broad genre of fiction that often involves speculations based on current or future science or technology. Science fiction is found in media as diverse as, but not limited to, literature, art, comic books, radio, television, movies, video games, board games, roleplaying games, and theater.

Science fiction is part of, and in organizational or marketing contexts can be synonymous with, the broader definition of speculative fiction. Speculative fiction is a category encompassing creative works incorporating imaginative elements not found in contemporary reality; this includes science fiction, fantasy, horror, and related genres. [1]

Science fiction often involves one or more of the following elements:

Contents

Exploring the consequences of such differences is the traditional purpose of science fiction, making it a «literature of ideas.» [2]

What is science fiction?

Science fiction is difficult to define as it includes a wide range of subgenres and themes. Author and editor Damon Knight summed up the difficulty by stating that, «science fiction is what we point to when we say it.» [3] Vladimir Nabokov argued that were people rigorous with their definitions, Shakespeare’s play The Tempest would have to be termed science fiction. [4]

According to SF writer Robert A. Heinlein, «a handy short definition of almost all science fiction might read: realistic speculation about possible future events, based solidly on adequate knowledge of the real world, past and present, and on a thorough understanding of the nature and significance of the scientific method.» [5] Rod Serling’s stated definition is «fantasy is the impossible made probable. Science Fiction is the improbable made possible.» [6]

Forrest J. Ackerman publicly used the term «sci-fi» at UCLA in 1954, [7] though Robert A. Heinlein had used it in private correspondence six years earlier. [8] As science fiction entered popular culture, writers and fans active in the field came to associate the term with low-budget, low-tech «B-movies» and with low-quality pulp fiction science fiction. [9] [10] [11] By the 1970s, critics within the field such as Terry Carr and Damon Knight were using «sci-fi» to distinguish hack-work from serious science fiction, [12] and around 1978, Susan Wood and others introduced the pronunciation «skiffy.» Peter Nicholls writes that «SF» (or «sf») is «the preferred abbreviation within the community of sf writers and readers.» [13] David Langford’s monthly fanzine Ansible includes a regular section «As Others See Us» which offers numerous examples of «sci-fi» being used in a pejorative sense by people outside the genre. [14]

Related genres and subgenres

Authors and filmmakers draw on a wide spectrum of ideas, but marketing departments and literary critics tend to separate such literary and cinematic works into different categories, or «genres,» and sub-genres. [15] These are not simple pigeonholes; works can overlap into two or more commonly-defined genres, while others are beyond the generic boundaries, either outside or between categories, and the categories and genres used by mass markets and literary criticism differ considerably.

Speculative fiction, fantasy, and horror

The broader category of speculative fiction [16] includes science fiction, fantasy, alternate histories (which may have no particular scientific or futuristic component), and even literary stories that contain fantastic elements, such as the work of Jorge Luis Borges or John Barth. For some editors, magic realism is considered to be within the broad definition of speculative fiction. [17]

Fantasy is closely associated with science fiction, and many writers, including Robert A. Heinlein, Poul Anderson, Larry Niven, C. J. Cherryh, Jack Vance, and Lois McMaster Bujold have worked in both genres, while writers such as Anne McCaffrey and Marion Zimmer Bradley have written works that appear to blur the boundary between the two related genres. [18] The authors’ professional organization SFWA is the «Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America». [19] SF conventions routinely have programming on fantasy topics, [20] [21] and fantasy authors such as J. K. Rowling and J. R. R. Tolkien (in film adaptation) have won the highest honor within the science fiction field, the Hugo Award. [22] Some works show how difficult it is to draw clear boundaries between sub-genres, for example Larry Niven’s The Magic Goes Away stories treat magic as just another force of nature and subject to natural laws which resemble and partially overlap those of physics.

However, most authors and readers make a distinction between fantasy and SF. In general, science fiction is the literature of things that might someday be possible, and fantasy is the literature of things that are inherently impossible. [6] Magic and mythology are popular themes in fantasy. [23]

It is common to see narratives described as essentially science fiction but «with fantasy elements.» The term «science fantasy» is sometimes used to describe such material. [24]

Horror fiction is the literature of the unnatural and supernatural, with the aim of unsettling or frightening the reader, sometimes with graphic violence. Historically it has also been known as «weird fiction.» It commonly deals with the nature of evil, psychological, technological, and fantastic. Undead and supernatural creatures like vampires and zombies are popular horror motifs. Classic works like Frankenstein and Dracula and the works of Edgar Allan Poe helped define the genre, [25] and today it is one of the most popular categories of movies. [26] Horror interlaps with both fantasy («Dark Fantasy») and science fiction, the latter notably seeing its genesis with the weird fiction of H.P. Lovecraft.

Related genres

Works in which science and technology are a dominant theme, but based on current reality, may be considered mainstream fiction. Much of the thriller genre would be included, such as the novels of Tom Clancy or Michael Crichton, or the James Bond films. [27]

Modernist works from writers like Kurt Vonnegut, Philip K. Dick, and Stanisław Lem have focused on speculative or existential perspectives on contemporary reality and are on the borderline between SF and the mainstream. [28]

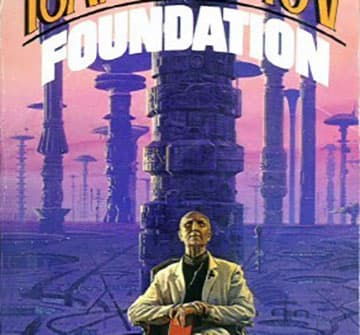

According to Robert J. Sawyer, «Science fiction and mystery have a great deal in common. Both prize the intellectual process of puzzle solving, and both require stories to be plausible and hinge on the way things really do work.» [29] Isaac Asimov, Anthony Boucher, Walter Mosely, and other writers incorporate mystery elements in their science fiction, and vice versa.

Subgenres

Hard SF

Hard science fiction, or «hard SF,» is characterized by rigorous attention to accurate detail in quantitative sciences, especially physics, astrophysics, and chemistry. Many accurate predictions of the future come from the Hard science fiction subgenre, but inaccurate predictions have also come from this category: Arthur C. Clarke accurately predicted geosynchronous communications satellites, [30] but erred in his prediction of deep layers of moondust in lunar craters. [31] Some hard SF authors have distinguished themselves as working scientists, including Robert Forward, Gregory Benford, Charles Sheffield, and Vernor Vinge. [32] Noteworthy hard SF authors, in addition to those mentioned, include Hal Clement, Joe Haldeman, Larry Niven, Jerry Pournelle and Stephen Baxter. In general, the distinction between «Hard» and «Soft» sci-fi is somewhat antiquated nowadays, with division by subgenre (for instance, cyberpunk or science fantasy) serving as a more common organization of science fiction.

Soft SF

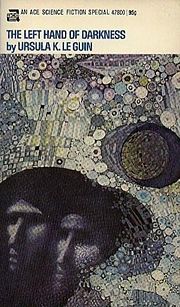

«Soft» science fiction is the antithesis of hard science fiction. It may describe works based on social sciences such as psychology, economics, political science, sociology, and anthropology. Noteworthy writers in this category include Ursula K. Le Guin, Robert A. Heinlein, and Philip K. Dick. [33] The term can describe stories focused primarily on character and emotion; SFWA Grand Master Ray Bradbury is an acknowledged master of this art. Some writers blur the boundary between hard and soft science fiction; for example Mack Reynolds’s work focuses on politics but anticipated many developments in computers, including cyber-terrorism.

Space Opera

Space Opera is a subgenre of speculative fiction or science fiction that emphasizes romantic adventure, and larger-than-life characters often set against vast exotic futuristic settings. «Space opera» was originally a derogatory term, a variant of «horse opera» and «soap opera,» coined in 1941 by Wilson Tucker to describe what he called «the hacky, grinding, stinking, outworn space-ship yarn»–i.e., substandard science fiction.[1] «Space opera» is still sometimes used with a pejorative sense. Space opera in its most familiar form was a product of the pulp magazines for the 1920s–1940s. Science fiction in general borrowed a great deal from the established adventure and pulp fiction genres, notably frontier stories of the American West and stories with exotic settings such as Africa or the orient, and space opera was no exception. There were often parallels between sailing ships and spaceships, between African explorers and space explorers, between oceanic pirates and space pirates. Related and similar is the ‘Space Western’, a genre playing with the conventions of the Western genre in a sci-fi setting, popularized lately by the Joss Whedon’s television show Firefly.

Despite the antiquated and pejorative origins of the term, space opera is still what many people think of when they think of science fiction in pop culture, from Buck Rogers to «Star Trek» and Star Wars.

Utopian and Dystopian Literature

Another branch of speculative fiction is the utopian or dystopian story. Satirical novels with fantastic settings and political motives may be considered speculative fiction; Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, Evgeny Zamyatin’s We and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World are examples.

Cyberpunk

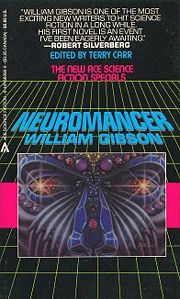

The Cyberpunk genre emerged in the early 1980s; the name is a portmanteau of «cybernetics» and «punk,» and was first coined by author Bruce Bethke in his 1980 short story «Cyberpunk». [34]

The genre was really launched by William Gibson’s book, Neuromancer which is credited for envisioning cyberspace, predicting the internet years before such a thing existed, and establishing cybyerpunk as one of the new facets of science fiction.

The time frame of cyberpunk literature is usually near-future and the settings are often dystopian. Common themes in cyberpunk include advances in information technology and especially the Internet (visually abstracted as cyberspace), (possibly malevolent) artificial intelligence, enhancements of mind and body using bionic prosthetics and direct brain-computer interfaces called cyberware, and post-democratic societal control where corporations have more influence than governments. Nihilism, post-modernism, and film noir techniques are common elements, and the protagonists may be disaffected or reluctant anti-heroes. Noteworthy authors in this genre are William Gibson, Bruce Sterling, Pat Cadigan, and Rudy Rucker. The 1982 film Blade Runner is commonly accepted as a definitive example of the cyberpunk visual style. [35]

Interestingly enough, the name of the sub-genre of cyberpunk gave rise to several related sub-genres, each denoted by the addition of the ‘punk’ suffix to a technology or theme to form a portmanteau denoting the union of that genre with the dark, edgy, authority-defiant attitude of the punk movement. For instance, steampunk adds punk sensibilities to Victorian technologies in works like William Gibson and Bruce Sterling’s novel The Difference Engine, the animation of Hayao Miyazaki, and Alan Moore’s comic League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. Other examples of these sub-sub-genres include biopunk including Frank Herbert’s The Eyes of Heisenberg and the Deus Ex computer games, or spacepunk including the Systems Malfunction roleplaying game and the anime Cowboy Bebop, also in part a Space Western.

Time Travel

Time travel stories have antecedents in the 18th and 19th centuries, and this subgenre was popularized by H. G. Wells’s novel The Time Machine. Time travel stories are complicated by logical problems such as the grandfather paradox. [36] Time travel stories are popular in novels, television series (such as Dr. Who), and as individual episodes within more general science fiction series (for example, «The City on the Edge of Forever» in Star Trek, «Babylon Squared» in Babylon 5, and «The Banks of the Lethe» in Andromeda.

Alternate History

Alternate history stories are based on the premise that historical events might have turned out differently. These stories may use time travel to change the past, or may simply set a story in a universe with a different history from our own. Classics in the genre include Bring the Jubilee by Ward Moore, in which the South wins the American Civil War and The Man in a High Castle, by Philip K. Dick, in which Germany and Japan win World War II. The Sidewise Award acknowledges the best works in this subgenre; the name is taken from Murray Leinster’s story «Sidewise in Time.»

Millitary

Military science fiction is set in the context of conflict between national, interplanetary, or interstellar armed forces; the primary viewpoint characters are usually soldiers. Stories include detail about military technology, procedure, ritual, and history; military stories may use parallels with historical conflicts. Heinlein’s Starship Troopers is an early example, along with the Dorsai novels of Gordon Dickson. Prominent military SF authors include David Drake, David Weber, Jerry Pournelle, S. M. Stirling, and Lois McMaster Bujold. Joe Haldeman’s The Forever War is a critique of the genre, a Vietnam-era response to the World War II-style stories of earlier authors. [37] Baen Books is known for cultivating military science fiction authors. [38] Television series within this sub-genre include Battlestar Galactica, Stargate SG-1 and Space: Above and Beyond.

History

As a means of understanding the world through speculation and storytelling, science fiction has antecedents as far back as ancient mythology, though precursors to science fiction as literature began to emerge during the Age of Reason with the development of science itself. [39] Following the eighteenth century development of the novel as a literary form, in the early nineteenth century, Mary Shelley’s books Frankenstein and The Last Man helped define the form of the science fiction novel; [40] later Edgar Allan Poe wrote a story about a flight to the moon. More examples appeared throughout the nineteenth century. Then with the dawn of new technologies such as electricity, the telegraph, and new forms of powered transportation, writers like Jules Verne and H. G. Wells created a body of work that became popular across broad cross-sections of society. [41] In the late nineteenth century the term «scientific romance» was used in Britain to describe much of this fiction.

In the early twentieth century, pulp magazines helped develop a new generation of mainly American SF writers, influenced by Hugo Gernsback, the founder of Amazing Stories magazine. [33] In the late 1930s, John W. Campbell became editor of Astounding Science Fiction, and a critical mass of new writers emerged in New York City in a group called the Futurians, including Isaac Asimov, Damon Knight, Donald A. Wollheim, Frederik Pohl, James Blish, Judith Merril, and others. [42] Other important writers during this period included Robert A. Heinlein, Arthur C. Clarke, and A. E. Van Vogt. Campbell’s tenure at Astounding is considered to be the beginning of the Golden Age of science fiction, characterized by hard SF stories celebrating scientific achievement and progress. [33] This lasted until postwar technological advances, new magazines like Galaxy under Pohl as editor, and a new generation of writers began writing stories outside the Campbell mode.

In the 1950s, the Beat generation included speculative writers like William S. Burroughs. In the 1960s and early 1970s, writers like Frank Herbert, Samuel R. Delany, Roger Zelazny, and Harlan Ellison explored new trends, ideas, and writing styles, while a group of writers, mainly in Britain, became known as the New Wave. [39] In the 1970s, writers like Larry Niven and Poul Anderson began to redefine hard SF. [43] Ursula K. Le Guin and others pioneered soft science fiction. [44]

In the 1980s, cyberpunk authors like William Gibson turned away from the traditional optimism and support for progress of traditional science fiction. [45] Star Wars helped spark a new interest in space opera, [46] focusing more on story and character than on scientific accuracy. C. J. Cherryh’s detailed explorations of alien life and complex scientific challenges influenced a generation of writers. [47] [48]

Emerging themes in the 1990s included environmental issues, the implications of the global Internet and the expanding information universe, questions about biotechnology and nanotechnology, as well as a post-Cold War interest in post-scarcity societies; Neal Stephenson’s The Diamond Age comprehensively explores these themes. Lois McMaster Bujold’s Vorkosigan novels brought the character-driven story back into prominence. [49] The television series Star Trek: The Next Generation began a torrent of new SF shows, [50] of which Babylon 5 was among the most highly acclaimed in the decade. [51] [52] A general concern about the rapid pace of technological change crystallized around the concept of the technological singularity, popularized by Vernor Vinge’s novel Marooned in Realtime and then taken up by other authors. Television shows like Buffy the Vampire Slayer and movies like The Lord of the Rings created new interest in all the speculative genres in films, television, computer games, and books.

Innovation

While SF has provided criticism of developing and future technologies, it also produces innovation and new technology. The discussion of this topic has occurred more in literary and sociological rather than in scientific forums.

Cinema and media theorist Vivian Sobchack examines the dialogue between science fiction film and the technological imagination. Technology does impact how artists portray their fictionalized subjects, but the fictional world gives back to science by broadening imagination. While more prevalent in the beginning years of science fiction with writers like Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, and Frank Walker, new authors like Michael Crichton still find ways to make the currently impossible technologies seem so close to being realized. [53]

This has also been notably documented in the field of nanotechnology with University of Ottawa Professor José Lopez’s article «Bridging the Gaps: Science Fiction in Nanotechnology.» Lopez links both theoretical premises of science fiction worlds and the operation of nanotechnologies. [54]

Ideas

This is a short list of common themes in science fiction.

Media and culture

As special effects, visual effects, computer-generated imagery, and other technologies make it possible to visually realize the imaginary worlds of science fiction, SF dominates the audiovisual media, including films, television, and computer games.

Films and Television

Most of the best-selling films of all time have been in the genres of science fiction, fantasy, and horror.

Examples of early silent SF films include Georges Méliès’s Le Voyage dans la Lune / A Trip to the Moon in 1902 and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis in 1927. Many of the movie serials of the 1940s and 1950s were science fiction, and led into early science-fiction television programming. Following the success of Star Wars in 1977, there was an explosion of new SF films. [55] Science-fiction films also explore more serious topics and can aim for high artistic standards, especially following Stanley Kubrick’s influential 2001: A Space Odyssey in 1968 and A Clockwork Orange in 1971, as well as Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner in 1982, and Scott’s other influential SF hit, Alien in 1979. Contemporary filmmakers have found science fiction to be a useful genre for exploring political, moral and philosophical issues, for example Gattaca on the question of genetic engineering, Starship Troopers as a satire of militarism and fascism and Minority Report on the questions of civil liberties and free will.

Science-fiction television dates from at least 1938, when the BBC staged a live performance of the science-fiction play R.U.R. [56] The first regularly scheduled science-fiction series to achieve a degree of popularity was Captain Video] and his Video Rangers in 1949. [57] The Twilight Zone, originally broadcast in the United States from 1959-1964, was the first successful speculative fiction series intended primarily for adults. [58] The TV serial Doctor Who first aired on BBC in 1963 and continues through to the present (with a hiatus from 1989 to 2004). Star Trek aired from 1966 to 1969, creating a new explosion of fan interest. Popular shows including Star Trek, Doctor Who, [59] and Stargate SG-1 have spun off related series, while Battlestar Galactica has inspired a «re-imagining». [60] A number of shows have later become the basis for films, among them Doctor Who, Star Trek, and Firefly. Television science fiction has exploited a variety of SF and fantasy traditions; Quantum Leap and Doctor Who are examples of time travel, Buffy the Vampire Slayer is one of the best-known horror or dark fantasy series, and Mystery Science Theater 3000 is one of the few comedy SF series. With the growing popularity of SF on television, dedicated channels have emerged to meet audience demand, such as Sci-Fi in the United States and Space: The Imagination Station in Canada.

Anime

Science fiction is a particularly popular genre of anime. Astro Boy, one of the first works of anime, is science fiction, and Hayao Miyazaki’s films are often either SF or alternate histories.

The Mecha subgenre is devoted specifically to stories involving giant robots and/or combat exoskeleton suits, like Macross. Classic science fiction anime works include Space Battleship Yamato, Akira, and the definitive cyberpunk anime Ghost in the Shell. Sentai refers to anime based on teams of superheroes. Other speculative genres, including fantasy and horror, are popular in anime. Emphasis on female characters and relationships, a common theme in anime generally, are found in SF anime like Bubblegum Crisis and Dirty Pair. Music is a very important component in anime such as Cowboy Bebop, a science fiction spacepunk/space western/film noir/crime drama with an emphasis on American music, especially jazz. (Cowboy Bebop refers to itself as «The work which has become a genre unto itself.»)

Science fiction has a long history of visual art. Artwork depicting a particular scene, setting, or character is known as illustration, which is used on book and magazine covers, movie posters, web sites, and other media, as well as inside books, comics, and games. WSFS has recognized science fiction art since the 1940s.

A short list of the most prominent SF artists includes:

Games

Beginning in the 1970s, the earliest role-playing games (or «RPGs»), such as Dungeons & Dragons and especially Traveler, had science fiction and fantasy settings, [61] and speculative settings continue to form the basis for the majority of RPGs up to the present. [62] There is significant crossover of interests between the fans of RPGs and science fiction. Popular science fiction role-playing games include the Star Wars RPG, several GURPS variants, Cyberpunk 2020, based on the works of William Gibson and the sci-fi/fantasy RPG Shadowrun.

In the 1980s, computer and video games adopted speculative settings and themes, either from original works or based on existing works. The virtual-reality nature of computer games, allowing game algorithms to simulate behavior impossible in reality lend themselves to science fiction characters and technological options within the game world. [63] The list of science fiction video and computer games is far, far too long to list. A truly huge portion of games have science fiction elements.

Comics

SF motifs and story lines have long been prominent in comic strips, comic books, and graphic novels. Buck Rogers first appeared in 1929, followed by Flash Gordon in 1935 and Superman in 1938. Since then, the superhero genre, in which an individual or team of characters with enhanced or superhuman abilities deals with challenges beyond the capability of ordinary people, has played a large role in the comics field.

Other Media

Early radio serials adapted Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers stories to radio, followed by other serials and radio magazine shows. Orson Welles’s famous dramatization of The War of the Worlds in 1938 panicked American listeners who believed the story was real. [64] The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is a famous BBC radio serial that was later adapted to television and film. There have been radio adaptations of the original Star Wars trilogy and The Lord of the Rings.

Science fiction and fantasy has been performed as live theater since the 1930s; a live musical version of The Lord of the Rings appeared in Toronto in 2006 and will soon be performed in London. [65] Vinyl albums have recorded science fiction performances, [66] and audiobooks on compact disc are growing in popularity, [67] available now in most bookstores. There have been SF ViewMaster reels, notably Sam Sawyer’s Trip to the Moon.

Some contemporary music explores science fiction themes and tell science fiction stories via concept albums, including the bands Muse and Coheed & Cambria.

Fandom and Community

Science fiction fandom is the «community of the literature of ideas… the culture in which new ideas emerge and grow before being released into society at large.» [68] Members of this community, fans, are in contact with each other at conventions or clubs, through print or online fanzines, or on the Internet using web sites, mailing lists, and other resources. Science fiction fandom is one of the oldest fandoms, and its antiquated terms and culture closely predicted the trends of later, more internet-based fandoms, and made up an interesting chapter in «geek» history.

SF fandom emerged from the letters column in Amazing Stories magazine. Soon fans began writing letters to each other, and then grouping their comments together in informal publications that became known as fanzines. [69] Once they were in regular contact, fans wanted to meet each other, and they organized local clubs. In the 1930s, the first science fiction conventions gathered fans from a wider area. [70] Conventions, clubs, and fanzines were the dominant form of fan activity, or «fanac,» for decades, until the Internet facilitated communication among a much larger population of interested people.

Awards

Among the most respected awards for science fiction are the Hugo Award, presented by the World Science Fiction Society at Worldcon, and the Nebula Award, presented by SFWA and voted on by the community of authors.

There are national awards, like Canada’s Aurora Award, regional awards, like the Endeavour Award presented at Orycon for works from the Pacific Northwest, special interest or subgenre awards like the Chesley Award for art or the World Fantasy Award for fantasy. Magazines may organize reader polls, notably the Locus Award.

Conventions, Clubs, and Organizations

Conventions (in fandom, shortened as «cons»), are held in cities around the world, catering to a local, regional, national, or international membership. General-interest conventions cover all aspects of science fiction, while others focus on a particular interest. Most are organized by volunteers in non-profit groups, though most media-oriented events are organized by commercial promoters. The convention’s activities are called the «program,» which may include panel discussions, readings, autograph sessions, costume masquerades, and other events. Activities that occur throughout the convention are not part of the program; these commonly include a dealer’s room, art show, and hospitality lounge (or «con suites»). [71] Conventions may host award ceremonies; Worldcons present the Hugo Awards each year. SF societies, referred to as «clubs» except in formal contexts, form a year-round base of activities for science fiction fans. They may be associated with an ongoing science fiction convention, or have regular club meetings, or both. Most groups meet in libraries, schools and universities, community centers, pubs or restaurants, or the homes of individual members. Long-established groups like the New England Science Fiction Association and the Los Angeles Science Fiction Society have clubhouses for meetings and storage of convention supplies and research materials.

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA) was founded by Damon Knight in 1965 as a non-profit organization to serve the community of professional science fiction authors. [19]

Fanzines and Online Fandom

The first science fiction fanzine, «The Comet,» was published in 1930. [72] Fanzine printing methods have changed over the decades, from the hectograph, the mimeograph, and the ditto machine, to modern photocopying. Subscription volumes rarely justify the cost of commercial printing. Modern fanzines are printed on computer printers or at local copy shops, or they may only be sent as email.

The best known fanzine (or «‘zine») today is Ansible, edited by David Langford, winner of numerous Hugo awards. Other fanzines to win awards in recent years include File 770, Mimosa, and Plotka. [73]

Artists working for fanzines have risen to prominence in the field, including Brad W. Foster, Teddy Harvia, and the late Joe Mayhew; the Hugos include a category for Best Fan Artists. [73]

The earliest organized fandom online was the SF Lovers community, originally a mailing list in the late 1970s with a text archive file that was updated regularly. [74] In the 1980s, Usenet groups greatly expanded the circle of fans online. In the 1990s, the development of the World-Wide Web exploded the community of online fandom by orders of magnitude, with thousands and then literally millions of web sites devoted to science fiction and related genres for all media. Most such sites are small, ephemeral, and/or very narrowly focused, though sites like SF Site offer a broad range of references and reviews about science fiction.

Fan Fiction

Fan fiction, known to aficionados as «fanfic,» is non-commercial fiction created by fans in the setting of an established book, movie, or television series. [75]

Such work may be in violation of copyright laws, [76] but some authors and media producers, if they are aware of it at all, choose to ignore its existence, provided that the fan authors derive no income from the work and that publication volumes are minimal. [77]

Fan fiction is written in a range of lengths and formats, from the 100-word «drabble» to multi-chapter epics where chapters may be released serially to readers before the next chapter is completed. [78] Fan videos appear on YouTube and other places; George Lucas even offers awards for best Star Wars fan videos. [79]

The plot, setting, and character content of the commercial works is known as «canon.» Much fan fiction creates small or large deviations from canon for various stories. The antonym of «canon» is «fanon». [80]

Notes

References

External links

All links retrieved November 2, 2019.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Science Fiction

Нау́чная фанта́стика (НФ) (от греч. phantastike — искусство воображать) — жанр в литературе и кино, где события происходят в мире, отличающемся от современной или исторической реальности по крайней мере в одном значимом отношении. Отличие может быть технологическим, физическим, историческим, социологическим и т. д., но не магическим (см. Фэнтези).

Автором термина «научно-фантастическая» является Яков Перельман

Содержание

История фантастики

Появление фантастики было вызвано промышленной революцией в XIX веке. Первоначально научная фантастика была жанром литературы, описывающим достижения науки и техники, перспективы их развития и т. д. Часто описывался (как правило, в виде утопии) мир будущего. Классическим примером такого типа фантастики являются произведения Жюля Верна.

Позднее развитие техники стало рассматриваться в негативном свете (антиутопия). Пример: «Машина времени» Герберта Уэллса. Антиутопия, кроме изменения техники в будущем, описывает негативные тенденции развития общества — так называемая социальная фантастика, появившаяся в XX веке. Самые известные примеры антиутопии: «Мы» Евгения Замятина, «Железная Пята» Джека Лондона, «Дивный Новый Мир» Олдоса Хаксли, «1984» Джорджа Оруэлла, «451 градус по Фаренгейту» Рэя Брэдбери.

В 1980-х годах начал набирать популярность антиутопический поджанр киберпанк. В нём высокие технологии соседствуют с тотальным социальным контролем и властью всемогущих корпораций. В произведениях этого жанра основой сюжета выступает жизнь маргинальных борцов с олигархическим Режимом, как правило, в условиях тотальной кибернетизации общества и социального упадка. Известные примеры: «Нейромант» Уильяма Гибсона, «Лабиринт отражений» Сергея Лукьяненко.

Сложился стереотип, что научная фантастика — развлекательный жанр. Нередко писатели пытаются его разрушить, превращая свои книги в серьёзные произведения, нагружая их скрытым философским смыслом. Примерами могут служить романы Хроники Дюны (Фрэнк Герберт), Основание (Айзек Азимов), Город (Клиффорд Саймак).

Фантастика в Советском Союзе

В 1934 во время всесоюзного съезда писателей известный детский писатель Самуил Яковлевич Маршак фактически раздавил своим авторитетом зарождающуюся советскую фантастику, полностью загнав её в прокрустово ложе детской литературы, определённое им самим лично. [1]

Жанры фантастики

От жанра научной фантастики в 20—30-х гг. XX столетия отпочковался жанр фэнтези, или «волшебной сказки для взрослых». Разделение этих жанров литературы относительно несложно в их крайних проявлениях: «твёрдой» научной фантастики и героической фэнтези, но между ними располагается целый спектр произведений, в середине которого отнесение книг сугубо к одному из жанров становится проблематичным (примером может служить цикл «Драконы Перна» Энн Маккефри).

Стимпанк

Жанр, созданный с одной стороны в подражание таким классикам фантастики как Жюль Верн и Альбер Робида, а с другой являющийся разновидностью пост-киберпанка. Иногда из него отдельно выделяют дизельпанк, соответствующий фантастике первой половине XX века.

Утопии, дистопии и антиутопии

Что характерно, дистопия и антиутопия характеризуются как сбывшиеся утопии. Начало жанра было положено ещё трудами античных философов, посвящённых созданию идеального государства. Самым известным из которых является «Государство» Платона, в котором он описывает идеальное (с точки зрения рабовладельцев) государство, построенное по образу и подобию Спарты, с отсутствием таких недостатков присущих Спарте, как повальная коррупция (а взятки в Спарте брали даже цари и эфоры), постоянная угроза восстания рабов, постоянный дефицит граждан и т. п. С концом античности, когда бывшую Римскую Империю заполонили варвары, а священники твердили о близком конце света, жанр утратил свою популярность — все жили одним днём в ожидании близкого конца света. А когда варвары христианизировались, то уже было не кому и не для кого писать утопии. Жанр пережил возрождение в Эпоху Возрождения, связанное с именем Томаса Мора, написавшего «Утопию». После чего начался расцвет жанра утопии с активным участием социал-утопистов. Позднее, с началом промышленной революции, начали появляться отдельные произведения в жанре антиутопии, изначально посвящённые критике сложившегося порядка. Ещё позднее появились произведения в жанре дистопии посвящённые критике утопий.

Апокалиптика и постапокалиптика

Космоопера

Классический жанр, прошедший длительную эволюцию от первых, строго научных произведений, написанных ещё учёными (например, Циолковский написал несколько НФ-произведений). В годы великой депрессии превратившийся в дешёвое развлечение, к которому термин «научная» часто неприменим. С наступлением эры космических полётов данный жанр снова стал научным, а с выходом «Звёздных войн» приобрёл некоторые черты, присущие фэнтэзи, в сочетании с эпичностью. Современные произведения могут сочетать общую научность с некоторыми фэнтезийными или мистическими элементами.

Киберпанк

Жанр, рассматривающий эволюцию общества под воздействием новых технологий, особое место среди которых уделено телекоммуникационным, компьютерным, биологическим, и, не в последнюю очередь, социальным. Фоном в произведениях жанра нередко выступают киборги, андроиды, суперкомпьютер, служащие технократичным, коррумпированным и аморальным органазациям/режимам. Для произведений жанра очень характерно присутствие мессии, нередко с сомнительным прошлым, одержимого идеей изменения мира путем убийства определённых ключевых персонажей или уничтожения организаций. В киберпанке, как в молодом, неокончательно сформированном, но очень многогранном жанре, можно заметить элементы других, более устоявшихся направлений фантастики. Киберпанк довольно депрессивен и мрачен, его дух может быть описан как «технократическая неоготика».

Пост-киберпанк

Пост-киберпанк делится на два крупных потока: нанопанк и биопанк. Некоторые относят к пост-киберпанку так же и стимпанк.

Критики и писатели о фантастике

«Научная фантастика — это прежде всего мысленный эксперимент. В текст вводится одно или несколько фантастических допущений. Во всем остальном действие развивается в соответствии с законами логики, физики и здравого смысла.

Фэнтези — это литература поступка. Исследуются моральные и этические аспекты поступков главных героев. Чтоб не затенять главное, требования к логичности и достоверности мира снижаются до необходимого минимума. Картина мира также часто дается упрощенной или сказочной.

Определения НФ и фэнтези не антагонистичны. Они лежат как бы в разных плоскостях. Что дает возможность создавать промежуточные и смешанные формы»

Интересные факты

Запущенный с Земли в августе 2007 года и совершивший в мае 2008 посадку на Марс в районе его северного полюса зонд Феникс привёз на Красную планету цифровую библиотеку научной фантастики. [2]

What is science fiction?

Among the works on the Greatest Literature of All Time list are several dozen titles that may be counted as science fiction, sci-fi, speculative fiction or SF.

But the separate Greatest Science Fiction list consists of much more than a subset of titles already appearing on the Greatest Literature list.

It actually comprises more than two hundred works that stand as the greatest in that genre, whatever you call it.

Where did all those extra titles come from? Like the larger literary list, the science fiction list is an amalgam of the assessments of many, many readers, writers, critics and scholars. I’ve read many of the works on the list myself, but I’ve consulted countless other references to judge how others have assessed the field.

For the overall approach to selecting works, you can consult the article «Creating the Greatest Literature of All Time list». The biases and the varying meanings of «great» discussed in that article, for example, also apply to this science fiction list.

I’m going to take this space, however, to discuss the specific questions and challenges that concern putting together a science fiction list. Namely, let’s deal with the tricky question of defining science fiction.

So what is SF anyway?

Hard definitions

Defining anything—especially anything embedded in our artistic or cultural practice— is tricky.

Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein didn’t like hard and fast definitions. He preferred something he called «family resemblances». When we use words to refer to things, we are really grouping them together by rough similarities that appeal to us in various contexts. For example, we use the word «family» all the time, but just try to define exactly what a family is, how to determine the members of a family. You’ll find every possible definition leaves out some members you would consider part of a family in some contexts and may include some you wouldn’t include in other.

This certainly applies to categories of literature—and especially to the SF genre. Let’s start with some standard definitions of «science fiction»:

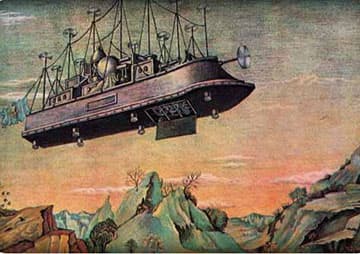

• Jules Verne, often considered the father of the field, never used the term, though roman de la science (scientific romance), which he used to describe his innovative tales of flying contraptions, submersible vehicles, and cannons to the moon, comes close. Despite his works being scientifically credible, he claimed not to predict future developments in his nineteenth-century fiction.

in which the revealed truths of Science may be given, interwoven with a pleasing story which may itself be poetical and true—thus circulating the knowledge of the Poetry of Science, clothed in a garb of the Poetry of Life.

That’s so pretty, we wish it were still true. But much of what we call science fiction today does not reveal «truths of Science». And many a pleasing story could be written to reveal such truths without being called science fiction.

• Nonetheless, this view of science fiction as edifying literature caught on after American pulp-magazine editor Hugo Gernsback revived the term in 1929. He discarded his own term, «scientifiction», as being too awkward and he promoted science fiction as

a factor in making the world a better place to live in, through educating the public to the possibilities of science and the influence of science on life. Science fiction would make people happier, give them a broader understanding of the world, make them more tolerant.

A noble dream, which still persists as a strain in SF.

But many stories of what we call science fiction are rather pessimistic about science or about the future of humankind, and some can be downright intolerant. Wilson’s and Gernsback’s «definitions» appear to be prescriptions for what science fiction could be, rather than descriptions of what it was—or is.

• The harder-nosed John W. Campbell, prominent editor and writer during science fiction’s «Golden Age» of the late 1930s to early 1950s, saw science fiction as running parallel to science fact:

Scientific methodology involves the proposition that a well-constructed theory will not only explain away known phenomena, but will also predict new and still undiscovered phenomena. Science fiction tries to do much the same—and writes up, in story form, what the results look like when applied not only to machines, but to human society as well.

This may be considered the definition of what became known as «hard science fiction», especially in the United States. (Incidentally, Campbell’s own early stories were really more about invention, with his youthful characters constantly creating new earth-shaking and space-shattering devices, giving rise to the thought that maybe it should have been called «tech fiction».)

• Campbell’s protйgй Isaac Asimov, who became one of the leading science fiction writers in the world, softened the definition while keeping the basis in science:

Science fiction is that branch of literature that deals with human responses to changes in the level of science and technology.

This seemed a handier definition, though developments in the SF field during the second half of the twentieth century would soon force a rethinking.

Fuzzy definitions

Much science fiction still adheres to the «hard science» methodology. But we’ve had an equal load of creative, artistic and even fanciful science fiction that does not. British and European work have especially deviated wildly from the hard-science prescription, and even much American SF since the 1960s would be unrecognizable as such to Campbell.

• Following Asimov, other definitions have retained a modified connection with science: science fiction is the literature responding to an increasingly scientific and technological society—dealing with our hopes and fears in this kind of world. Russian-born (like Asimov) writer Reginald Bretnor, for example, referred to fiction

in which the author. takes into effect in his stories the effect and possible future effects on human beings of scientific methods and scientific fact.

Problem with this: a lot of modern literature does this without being known as science fiction. And a lot of what we do call science fiction uses science or technology—space ships, time machines, drugs, etc.—essentially as plot devices without having much to say about how these toys are affecting our psyches or societies.

• So maybe science fiction is about the future then? Usually a technologically advanced future? This is the description of the field you often hear: science fiction as prophecy. Science fiction great Robert Heinlein, known for his «future histories», said a short definition of «almost all science fiction» might be:

realistic speculation about possible future events, based on adequate knowledge of the real world, past and present, and on a thorough understanding of the scientific method.

However, many science fiction plots take place in the past or present, or in parts of the universe with no time relation to ourselves. The proportion of science fiction that seriously purports to predict our future, or to warn us against a possible future if we don’t change our ways, is actually quite limited.

• No wonder, Heinlein added: «To make the definition cover all science fiction (instead of ‘almost all’) it is necessary only to strike out the word ‘future’.» Science fiction and fantasy writer Barry N. Malzberg came up with a summarizing definition of science fiction as

That branch of fiction that deals with the possible effects of an altered technology or social system on mankind in an imagined future, an altered present, or an alternative past.

• So maybe it’s not just about future times but about other situations in space and time, in other dimensions, in other realities. The term «speculative fiction» became popular as an alternative to «science fiction». Canadian writer Judith Merril defined speculative fiction as

stories whose objective is to explore, to discover, to learn, by means of projection, extrapolation, analogue, hypothesis-and-paper-experimentation, something about the nature of the universe, of man, of ‘reality’.

But we have our old problem here: if we make our definition broad enough to include all SF, it comes to include almost all literature, not just science fiction. It’s hard to think of any novel that does not involve something imagined by the author.

Isaac Asimov had such an objection to this phrase:

To me. «speculative» seems a weak word. It is four syllables long and is not too easy to pronounce quickly. Besides, almost anything can be speculative fiction. A historical romance can be speculative; a true-crime story can be speculative. «Speculative fiction» is not a precise description of our field and I don’t think it will work. In fact, I think «speculative fiction» has been introduced only to get rid of «science» but to keep «s.f.»

The SF family

• A most sophisticated, insightful and difficult definition of science fiction comes from former Yugoslavian—now Canadian—poet and professor Darko Suvin, who has written at least three books trying to pin down the field. At one point he declares:

SF is distinguished by the narrative dominance or hegemony of a fictional «novum» (novelty, innovation) validated by cognitive logic.

Suvin is putting forward a variation on the what-if definition. In every SF story there is one modification to current reality («novum») on which the story hinges. Most importantly, it is followed through with logical consistency—to become part of our store of knowledge about things. This definition is more practical than most because having an innovation to current reality at the centre of the story separates SF from general literature while, at the other end of the SF spectrum, cognitive validation separates it from wildly fantastic stories.

However, now we have the problem of being too exclusive. Strictly applied, this definition would exclude some of the more imaginative literature that the world considers science fiction. Some writers—the names Brian Aldiss, Harlan Ellison, J.G. Ballard, and Philip K. Dick come to mind—seem not to care whether their plots hold together cognitively, as long as they work viscerally. That is, they want readers to go with the flow, however credible the scientific or logical underpinnings are.

• The winner: We could go on and on with definitions of SF and their failings, but I think it’s time to settle for the final infallible definition: science fiction is [drum roll]

whatever we call science fiction.

Others have put it differently: «anything published as science fiction» (Normal Spinrad) or «a label applied to a publishing category. subject to the whims of editors and publishers» (John Clute and Peter Nicholls).

But stop groaning. This is not as tautological or downright wimpy as it may at first seem. It’s an acceptance of the family resemblances approach mentioned earlier. It’s saying we amorphously group together literature that has bits of all the above definitions into one family, but members of the family don’t necessarily meet all the criteria, and a few individuals that do meet one or two of the criteria still aren’t considered members.

Yet, somehow, despite holding this fuzziest of fuzzy definitions of science fiction, when we look for a novel in a book store, we usually have a pretty good idea whether we should be looking in the Science Fiction section or elsewhere. And in most cases most of us would agree on where to look. Mostly.

True, several genre-busting books are hard to place, because they could fall into several categories. Lord of the Rings? Nineteen Eighty-Four? Utopia? Dracula? The Handmaid’s Tale? And over time, the borders of the categories may shift.

But for most books at any given time, we can walk directly to the appropriate section. We have an idea of what science fiction is—derived from all the references to «science fiction» we’ve heard in our lives. We have a sort of social consensus about how we use that term «science fiction» in everyday language.

That consensus, which I’ve learned to identify through my own life experience among language speakers, is what I use to determine what is science fiction for the Greatest Science Fiction list.

Of course, the consensus is not complete nor final. Never will be. So let’s look at some of the more contentious border disputes, which paradoxically can help us clarify what we mean by «science fiction».

Border disputes

Several other literary genres are sometimes lumped in with science fiction, but are not included in the list of The Greatest Science Fiction of All Time. On the whole they are not included because most science fiction readers would not consider them science fiction—as far as I can tell from my own experience among language speakers using the words «science fiction» or analogous terms.

But here are a few rationales for their exclusion:

• Horror: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is often considered one of the first science fiction novels as well as a great work of horror, while Bram Stoker’s Dracula is usually left in only the latter category. Why the difference? Possibly because in the novels Shelley’s monster was created by science while Stoker’s was supernaturally invoked. If we accepted Dracula as SF, then we might also have to accept every ghost story, Greek myth and fairy tale, not to mention many religious texts such as the Bible. Moreover, Frankenstein is often seen as a response to technological advances and a warning about scientific pride.

However, it may be noted Europeans are more likely than North Americans to count Dracula and other horror tales among sci-fi’s progenitors, sometimes citing the supposedly psychological science exploited in that novel.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde may be seen as situated halfway between Frankenstein and Dracula on the science fiction-horror spectrum. Scientific means are adduced for the creation of a monster in that story but those means are somewhat irrelevant to the point of the story. The cause of Doctor Jekyll’s transformation could have been a magical spell and the essential horror of the tale would remain. A similar point could be made concerning some of Edgar Allen Poe’s works. I’ve included Jekyll and Hyde and at least one Poe story on the Greatest Science Fiction list—to be as inclusive as possible, without being ridiculously liberal.

• Fantasy: This is a genre as difficult to define as science fiction. Some publications and book stores put them together as «science fiction and fantasy» (or in the opposite order). The fact that both names are used, however, is a hint they are not identical, although the dividing line is somewhat blurred.

The difference is sometimes spelled out along these lines: science fiction looks at possibilities given our known natural laws, while fantasy looks at possibilities that break our known natural laws. So machines flying to the moon are science fiction, while dragons flying on earth are fantasy. Advanced technology is SF, while magic spells are fantastic.

You might ask: what about SF that has spaceships flying faster than the speed of light or other devices that break known natural laws? Two answers: 1) It may be bad science fiction. 2) The author is supposing that scientific means of circumventing limitations such as the speed of light have been found, which is different from having a wizard mutter a few magic words to whisk people across the universe, which would be the supernatural fantasy approach.

On the borderline may be the Dragonflight books of Anne McCaffrey, in which the beasts fly and other psychic phenomena occur, but are given scientific underpinnings, however flimsy. Somehow though, the consensus seems to be that her books feel more like fantasy than sci-fi.

And then there’s the fantastic (in all senses) World of Tiers series by Philip Josй Farmer, which I never have been able to categorize. But it is a little closer to SF and so is included on the science fiction list, along with his more straightforwardly SF series, Riverworld.

More fabulous anomalies

• Fabulation and Slipstream: Fabulation is a latter twentieth-century trend in literature in which some elements of the story are clearly fantastic while others are natural. Some critics would put fabulists like Jorge Luis Borges and Thomas Pynchon, and a whole host of Latin American magic realists, in the SF category. For the most part, however, this has been considered a separate genre of fiction or a part of the mainstream literary tradition.

Related is the slipstream, a take-off on «mainstream», as fans have taken to calling stories that involve some science fiction elements but aren’t really about those elements, focusing more on traditional literary issues. It’s often considered a derogatory term, implying mainstream writers are just throwing in some sci-fi bits to spice up their stories.

However, many accepted science fiction works, such as by Philip K. Dick and Kurt Vonnegut, might also be considered slipstream by a strict definition. Their stories can include science fiction devices such as space flight, time travel or alternative social structures, yet concentrate entirely on questions of morality or relationships causally unrelated to those devices. It’s a judgment call whether to include them in the science fiction category, but my tendency is to do so, at least for established SF authors.

• Progenitors of SF: Claims have been made for stories going back to ancient literature—if not as science fiction, at least as forerunners of science fiction. Thus mythology such as Gilgamesh and the Iliad are claimed as proto-science fiction. Mainly for their fantasy elements.

However, without any connection with science or technology, these just don’t feel like science fiction, even in the genre’s infancy. The earliest works on the Greatest Science Fiction list tend to involve using science or technology to either fly to the moon (a common dream once we became astronomically sophisticated) or build human-like creatures (a common dread, it seems, once we began to think of the human body as a machine). It seems to take a certain materialistic, post-mythological understanding of the world for the emergence of a literature we can call science fiction.

• Utopian and Dystopia Literature: This is a tough one. Extraordinary voyages make up a lot of what we call science fiction and often the voyages purport to lead to the discovery of other civilizations, typically depicted either as ideally organized or as nightmares to be avoided. Often this is the author’s point: he is taking us to another land to give himself an opportunity to pontificate upon the best or worst social systems we may adopt ourselves. Or he’s using the comparison of the imagined world with our current society to highlight aspects of our own we wouldn’t have otherwise noticed.

Generally, the more politically or philosophically inclined of these works, like Thomas More’s Utopia and Samuel Butler’s Erewhon, are not considered science fiction. Others in which the science or technology are more central seem to fall more comfortably into the science fiction camp. This does not mean however that science fiction cannot be politically or philosophically interesting; works such as Ursula Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed are both of those, and are considered solidly SF.

At some point in the early twentieth century, fictional utopias and dystopias stopped being discovered elsewhere on Earth during our own time and moved into future or futuristic settings. It’s been suggested that this is when fantastic voyages became science fiction. Indeed the two most famous utopian/dystopian novels around that time—Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four—have futuristic elements and are included on the science fiction list. A more recent example is Margaret Atwood’s A Handmaid’s Tale.

Meanwhile B.F. Skinner’s Walden Two, which was written in that period also and talks a lot about science but takes place contemporarily rather than in the future, is not considered science fiction. Rather, its didactic format leaves it considered a work of psychology or philosophy, like Plato’s Republic.

New words for an old world

In trying to settle these boundary disputes, one cannot always be a hundred percent certain why particular works are considered to fall on either side of the line. The boundary is blurry and the decisions are inconsistent. For the Greatest Science fiction list, decisions try to follow the consensus of language users, however erratic that may be.

But even the consensus is unclear at times. It could be said that here, as in other social affairs, we are always seeking a consensus as to what the consensus is.

That’s as definitive as I—or anyone—can get.

I’ll leave you with one more philosophical quote, this from Ludwig Feuerbach:

We people the other planets, not that we may place there different beings from ourselves, but more beings of our own or of a similar nature.

This was written in 1841, before the term «science fiction» was known, and Feuerbach’s target was not literature but religion. But the insight stands today in regard to SF. Whatever our definition—whether we think it’s about science, about the future or about other realities—science fiction is, like all art, about us here and now.

You see, science fiction is not really so different from any other fiction in its essentials. What it says to us is not so different.

Science fiction

The concept of science fiction covers various genres of literature and film featuring some fictitious element based on real or hypothetical science and technology. Generally, science fiction is set in the future, but some works take place in the modern day (or even in the past) but still prominently feature science and technology as a theme.

Contents

Overview [ edit ]

Science fiction may take place in a futuristic setting, alternate universe (including a novel planet, culture, society, etc.) or involve a plot-driving idea somehow related to science, or an extrapolation thereof. It took off in pulp magazines in the early 20th century, after a few 19th century precursors (H.G. Wells and Jules Verne, for example). Interestingly, a book from 2nd century Roman Greece entitled «True History», which features among other things, aliens and space travel, has been cited as the earliest known work that could be categorized as «science fiction». [1]

In the popular perspective, «sci-fi» is blended with, and even assumed to be part of, the «fantasy» genre, within the umbrella of speculative fiction. Science fiction is typically divided into two schools: hard science fiction and soft science fiction, however what defines either is very vague. It is generally accepted that there is a «sliding scale» of hardness rather than something just being simply «hard» or «soft,» although sometimes the terms hard or soft science fiction means whatever people want them to mean, and you’ll rarely see much consensus except in obvious cases such as Star Wars (‘»soft») and 2001: A Space Odyssey («hard»). Science fiction is also often distinguished by setting, such as alternate reality, cyberpunk, military science fiction, etc. Many fans of science fiction literature (and certain authors) don’t like using the term «sci-fi» to refer to serious works in the genre, preferring instead «SF.»

Hard or soft? [ edit ]

Science fiction is typically divided into two over-arching genres: hard and soft. Neither term is considered pejorative in the general sense, just a demarcation of the two general styles (think 2001: A Space Odyssey vs. Star Wars). Hard science fiction generally explores ideas generated from actual real («hard,» or serious) science, theoretical or not, and how people might deal with such situations. The «big three» of science fiction – Heinlein, Asimov, and Clarke – often tried to write stories that did nothing more than project or extrapolate real science, usually into a hypothetical future. This is the definition that some fans use when praising scientifically interesting works and says nothing about presence or lack of «literary» quality or the existence of themes other than science. Another definition of hard science fiction has also been used as a somewhat derogatory term [2] [3] to define science fiction that focuses more on accurate scientific data than on literary devices such as character development. Indeed, some hard science fiction fans consider focus on characters and their relationships and personal experiences to be of little use to the story. In this definition, scientific accuracy alone is not enough for a work be lumped into the hard science fiction genre, and focus on technical scientific details over everything else is a must. This definition refers to works where instead of science being a means to an end, the science is the end. Less commonly, the term may be used to define any work that has a hard focus on scientific detail, even if the science is not completely within the realms of possibility. An even less common definition is «science fiction based on hard sciences (physics, chemistry, etc).» Utopian and dystopian stories may use the extrapolation of academic social sciences and real world politics, but they are typically not considered hard science fiction without additional STEM focused elements.

Soft science fiction is even less rigorously defined, and its definition is the subject of much debate and controversy within the community. When taken to simply mean «science fiction that’s not hard,» it is the most common form of science fiction seen in all forms of media. Soft science fiction include works that either have little or no focus on the science aspect of the story, instead focusing on plot, character and/or action and adventure, or works that do focus on the science, but science that is mostly fictional. Devices such as faster-than-light travel, instant teleportation and time travel are often used. Adventure/exploration tropes and themes such as «good versus evil» are relatively common. There may also be considerable overlap with fantasy (in such cases it is generally regarded as «science fantasy»). Star Wars (arguably science fantasy), Dr. Who, and Back to the Future are examples of works that fall into the softer end of science fiction. Rarely, the term soft science fiction may also sometimes be used pejoratively to purely mean works that are all style and no substance, with focus on little more but spectacle and entertainment, no matter how realistic the actual scientific devices are. Some of the more «literary» science fiction writers generally dabble into the softer areas of science fiction, focusing on the issues presented by the new technology, and how the characters are affected by it, rather than just using them simply as plot devices. Some of the more popular authors of the kind include Philip K. Dick, Gene Wolfe, Jack Vance, and Ursula K. Guin. More satirical/humorous works (The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Futurama, Red Dwarf, Fallout, etc.) also tend to fall into soft science fiction. Science fiction video games also tend to lean soft, since a video game is usually judged on immersiveness and presentation, neither of which requires strict scientific rigor.

Some science fiction writers try to synthesize hard and soft science fiction if they want to include «soft» elements while writing an overall «hard» story by introducing plot elements that present-day scientific understanding either does not allow or allows in only theory, but trying to explain said elements in a rigorous, internally consistent way that does not explicitly contradict present-day science, and keeping the rest of the story as hard as possible. FTL travel (usually explained either via wormholes as in Interstellar, or through applications of as-yet-undiscovered exotic matter as in Mass Effect) and truly sentient artificial intelligence (as seen in Ex Machina) are two common features of stories like this.

Examples [ edit ]

Science fiction as commentary on social reality [ edit ]

Much of science fiction has a social message. George Orwell’s 1984 was primarily intended as a satire, but was dressed up as science fiction. Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 played with information control techniques as had been tried with varying degrees of success in totalitarian regimes. And then there’s Philip K. Dick, who experimented with every kind of society in his fiction. Ursula K. LeGuin also wrote science fiction novels with social themes, including feminist themes. Modern near-future science fiction (William Gibson, e.g.) often depicts corporations ruling the world, whether overtly or covertly, whereas far-future science fiction is often virtually anarchistic, using the assumption of ultra-cheap power and total information availability (Iain M. Banks, e.g.) as justification. The precious spice in Dune, which is found only on Arrakis and mined amid terrorist attacks from the vaguely Islamic Fremen, stands in for petroleum here on Earth. H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds was written as a deconstruction of British Imperialism through the perspective of the natives; depicting the United Kingdom as being overwhelmed by the technologically superior Martians, who were defeated not by spears and arrows machine guns and cannons but from malaria, sleeping sickness the common cold. Interestingly, The Island of Doctor Moreau has a similar theme, but one in which the British Empire Doctor is forcibly uplifting the local Africans beasts through mass torture and «education» mass torture and «education». Once the British leave Doctor dies, the Africans beasts quickly revert back to their original nature. It’s pretty blatant that Wells was extremely racist, but at least his view was «leave the people alone».

Even with the works focused more on the adventure and spectacle, many science fiction aficionados disagree on how serious a particular work should be taken. For example, the various Star Trek series could be formulaic, but did regularly explore themes of philosophy and morality, as well as some ideas from real science. Star Wars, for all its cliched romance, [note 1] nodded at themes such as genocide, racism, fascism, the importance of teamwork, fire-forged friendships, and how people will give up everything for the illusion of safety even if it means their own liberty. The Matrix was primarily a blockbuster action film, but did explore thought-provoking themes of simulated reality. The sequels, less so.

The best science fiction, whether soft or hard, will often have important themes, science related or otherwise, and contrary to popular belief, can be just as literary as mainstream fiction.

Fundies don’t like science fiction:

Sci-fi arose in the late 19th and early 20th century as a product of an evolutionary worldview that denies the Almighty Creator. In fact, evolution IS the pre-eminent science fiction. Beware! [4]

Notable sub-genres [ edit ]

Notable authors [ edit ]

Movies and television [ edit ]