What is the 1951 convention about

What is the 1951 convention about

What is the 1951 Refugee Convention—and How Does It Support Human Rights?

The UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees—also known as “The 1951 Refugee Convention”— was formally adopted 70 years ago on July 28, 1951. The agreement is considered the “centrepiece of international refugee protection” and legally binds country signees to recognize and protect people who flee their countries of nationality because of persecution or conflict.

While the Convention is no longer the only international protection regime for refugees, it established an important moral and legal precedent in global refugee response. It also continues to serve as a reference point for refugee rights agreements around the world.

At the time of its creation, the 1951 Refugee Convention was the most comprehensive codification of the international rights of refugees.

Prior to the 1951 Refugee Convention, non-governmental organizations, like the Red Cross, were the primary actors in refugee response, administering ad hoc emergency relief. After 1921, the League of Nations established and protected a legal status for refugees, but limited its scope to specific refugee groups on a case-by-case basis. The 1951 Refugee Convention was created after World War II and legally recognized–for the first time–refugees in the region based on their experience of displacement, rather than their country of origin. However, the Convention was originally limited in scope to persons fleeing persecution in Europe.

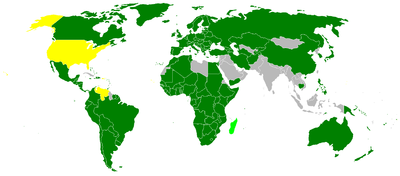

The 1951 Refugee Convention has since grown to govern a majority of the global refugee rights system. The 1967 Protocol removed the Convention’s geographic and temporal limitations so that it applied universally. While only twenty-six states participated in the original Convention, 145 states have since ratified it, which means they have officially approved the Convention and intend to comply with its rules. Initially a temporary regional agreement, the 1951 Refugee Convention is now an enduring global institution

The 1951 Refugee Convention defined a new category of protected persons and specified what it means to respect refugees’ human rights.

The 1951 Refugee Convention provided lasting contributions to the international legal system on refugee rights, including a single universal definition of the term “refugee” as well as the core principles of non-discrimination, non-penalization and non-refoulement. The Convention defines a refugee as someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of nationality “owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.” And, through the principle of non-refoulement, the agreement holds that no state can expel or return (“refoul”) a refugee to a territory where their life or freedom would be threatened. Signees of the 1951 Refugee Convention are held to its definitions and principles, and many state parties, such as the US, have implemented all or parts of the Convention into their national refugee policies.

The 1951 Refugee Convention is influential beyond official state parties to the Convention as well. For example, the principle of non-refoulement applies to all migrants at all times, irrespective of migration status, and is fortified by multiple international human rights agreements. Additionally, while about one quarter of UN member states have not ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention, many states are still influenced by norms established by the Convention and a desire to engage diplomatically with UNHCR and the Convention’s state parties. This means that even non-party states have incentive to recognize refugee rights and follow the Convention’s core principles. In essence, the 70-year-old Convention provides guidance that remains relevant almost everywhere in the world today.

A lot has changed since 1951, and new displacement contexts call for new approaches to refugee rights.

Despite the 1951 Refugee Convention’s historical contributions to global refugee protection, a growing movement of governments, scholars and NGOs has called into question the appropriateness of a Euro-centric, World War II-era convention for today’s new and changing displacement situations. And there are a number of reasons for rethinking and expanding upon the existing agreement. For example, the Convention’s definition of the term “refugee” does not accommodate a growing population of people who have experienced displacement, including those displaced due to climate change, food insecurity or non-state terrorism or those who are displaced internally. The agreement also lacks guidance on long-term (or “protracted”) displacement, of which a growing proportion of displacement experiences are.

Importantly, a number of other regional agreements already exist that supplement the 1951 Refugee Convention to better accommodate their modern contexts, including the 1984 Cartagena Declaration (among Central American states, Mexico and Panama) and the 1969 OAU Convention (among African states). Agreements like these expanded refugees’ access to rights and have provided new models for what refugee rights agreements can look like going forward. While regional agreements do not guarantee state participation, they are often widely integrated into national refugee laws and policies, providing greater leverage for legal and advocacy efforts in support of refugee rights.

The 1951 Refugee Convention has served as a critical guidepost for many countries over the last several decades. However, much more must be done to ensure people of forced displacement can meaningfully rebuild their lives wherever they find themselves. Asylum Access advocates for a response to forced displacement that recognizes, restores and amplifies the power of those who have been forced from their home countries. Learn more about our work here.

What is the 1951 convention about

Convention relating to the Status of Refugees

Geneva, 28 July 1951

Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees

New York, 31 January 1967

The 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, with just one “amending” and updating Protocol adopted in 1967 (on which, see further below), is the central feature in today’s international regime of refugee protection, and some 144 States (out of a total United Nations membership of 192) have now ratified either one or both of these instruments (as of August 2008). The Convention, which entered into force in 1954, is by far the most widely ratified refugee treaty, and remains central also to the protection activities of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

The historical context also helps to explain both the nature of the Convention and some of its apparent limitations. Just six years before its conclusion, the Charter of the United Nations had identified the principles of sovereignty, independence, and non-interference within the reserved domain of domestic jurisdiction as fundamental to the success of the Organization (Article 2 of the Charter of the United Nations). In December 1948, the General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, article 14, paragraph 1, of which recognizes that, “Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution”, but the individual was only then beginning to be seen as the beneficiary of human rights in international law. These factors are important to an understanding of both the manner in which the 1951 Convention is drafted (that is, initially and primarily as an agreement between States as to how they will treat refugees), and the essentially reactive nature of the international regime of refugee protection (that is, the system is triggered by a cross-border movement, so that neither prevention, nor the protection of internally displaced persons come within its range).

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the 1951 Convention

After extensive discussions in its Third Committee, the General Assembly moved to replace the IRO with a subsidiary organ (under Article 22 of the Charter of the United Nations), and by resolution 428 (V) of 14 December 1950, it decided to set up the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees with effect from 1 January 1951. Initially set up for three years, the High Commissioner’s mandate was regularly renewed thereafter for five-year periods until 2003, when the General Assembly decided “to continue the Office until the refugee problem is solved” (resolution 58/153 of 22 December 2003, paragraph 9).

The High Commissioner’s primary responsibility, set out in paragraph 1 of the Statute annexed to resolution 428 (V), is to provide “international protection” to refugees and, by assisting Governments, to seek “permanent solutions for the problem of refugees”. Its protection functions specifically include “promoting the conclusion and ratification of international conventions for the protection of refugees, supervising their application and proposing amendments thereto” (paragraph 8 (a) of the Statute).

A year earlier, in 1949, the United Nations Economic and Social Council appointed an Ad Hoc Committee to “consider the desirability of preparing a revised and consolidated convention relating to the international status of refugees and stateless persons and, if they consider such a course desirable, draft the text of such a convention”.

The Ad Hoc Committee decided to focus on the refugee (stateless persons were eventually included in a second convention, the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons), and duly produced a draft convention. Its provisional draft drew on IRO practice under its Constitution, identified a number of categories of refugees, such as the victims of the Nazi or Falangist regimes and those recognized under previous international agreements, and also adopted the general criteria of well-founded fear of persecution and lack of protection (See United Nations doc. E/AC.32/L.6, 23 January 1950).

The Conference met in Geneva from 2 to 25 July 1951 and took as its basis for discussion the draft which had been prepared by the Ad Hoc Committee on Refugees and Stateless Persons, save that the Preamble was that adopted by the Economic and Social Council, while article 1 (definition) was as recommended by the General Assembly and annexed to resolution 429 (V). On adopting the final text, the Conference also unanimously adopted a Final Act, including five recommendations covering travel documents, family unity, non-governmental organizations, asylum, and application of the Convention beyond its contractual scope.

Notwithstanding the intended complementarity between the responsibilities of the  UNHCR and the scope of the new Convention, a marked difference already existed: the mandate of the UNHCR was universal and general, unconstrained by geographical or temporal limitations, while the definition forwarded to the Conference by the General Assembly, reflecting the reluctance of States to sign a “blank cheque” for unknown numbers of future refugees, was restricted to those who became refugees by reason of events occurring before 1 January 1951 (and the Conference was to add a further option, allowing States to limit their obligations to refugees resulting from events occurring in Europe before the critical date).

The Convention Refugee Definition

Article 1A, paragraph 1, of the 1951 Convention applies the term “refugee”, first, to any person considered a refugee under earlier international arrangements. Article 1A, paragraph 2, read now together with the 1967 Protocol and without the time limit, then offers a general definition of the refugee as including any person who is outside their country of origin and unable or unwilling to return there or to avail themselves of its protection, on account of a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular group, or political opinion. Stateless persons may also be refugees in this sense, where country of origin (citizenship) is understood as “country of former habitual residence”. Those who possess more than one nationality will only be considered as refugees within the Convention if such other nationality or nationalities are ineffective (that is, do not provide protection).

The refugee must be “outside” his or her country of origin, and the fact of having fled, of having crossed an international frontier, is an intrinsic part of the quality of refugee, understood in its ordinary sense. However, it is not necessary to have fled by reason of fear of persecution, or even actually to have been persecuted. The fear of persecution looks to the future, and can also emerge during an individual’s absence from their home country, for example, as a result of intervening political change.

Persecution and the Reasons for Persecution

Although the risk of persecution is central to the refugee definition, “persecution” itself is not defined in the 1951 Convention. Articles 31 and 33 refer to those whose life or freedom “was” or “would be” threatened, so clearly it includes the threat of death, or the threat of torture, or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. A comprehensive analysis today will require the general notion to be related to developments within the broad field of human rights (cf. 1984 Convention against Torture, article 7; 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, article 3; 1950 European Convention on Human Rights, article 6; 1969 American Convention on Human Rights, article 5; 1981 African Charter of Human and Peoples’ Rights).

At the same time, fear of persecution and lack of protection are themselves interrelated elements. The persecuted clearly do not enjoy the protection of their country of origin, while evidence of the lack of protection on either the internal or external level may create a presumption as to the likelihood of persecution and to the well-foundedness of any fear. However, there is no necessary linkage between persecution and Government authority. A Convention refugee, by definition, must be unable or unwilling to avail him- or herself of the protection of the State or Government, and the notion of inability to secure the protection of the State is broad enough to include a situation where the authorities cannot or will not provide protection, for example, against the persecution of non-State actors.

The Convention requires that the persecution feared be for reasons of “race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group (added at the 1951 Conference), or political opinion”. This language, which recalls the language of non-discrimination in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and subsequent human rights instruments, gives an insight into the characteristics of individuals and groups which are considered relevant to refugee protection. Persecution for the stated reasons implies a violation of human rights of particular gravity; it may be the result of cumulative events or systemic mistreatment, but equally it could comprise a single act of torture.

Persecution under the Convention is thus a complex of reasons, interests, and measures. The measures affect or are directed against groups or individuals for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion. These reasons in turn show that the groups or individuals are identified by reference to a classification which ought to be irrelevant to the enjoyment of fundamental human rights.

The Convention does not just say who is a refugee, however. It goes further and sets out when refugee status comes to an end (article 1C; for example, in the case of voluntary return, acquisition of a new, effective nationality, or change of circumstances in the country of origin). For particular, political reasons, the Convention also puts Palestinian refugees outside its scope (at least while they continue to receive protection or assistance from other United Nations agencies (article 1D)), and excludes persons who are treated as nationals in their State of refuge (article 1E). Finally, the Convention definition categorically excludes from the benefits of refugee status anyone whom there are serious reasons to believe has committed a war crime, a serious non-political offence prior to admission, or acts contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations (article 1F). From the very beginning, therefore, the 1951 Convention has contained clauses sufficient to ensure that the serious criminal and the terrorist do not benefit from international protection.

Non-refoulement

Besides identifying the essential characteristics of the refugee, States party to the Convention also accept a number of specific obligations which are crucial to achieving the goal of protection, and thereafter an appropriate solution.

Foremost among these is the principle of non-refoulement. As set out in the Convention, this prescribes broadly that no refugee should be returned in any manner whatsoever to any country where he or she would be at risk of persecution (see also article 3, 1984 Convention against Torture, which extends the same protection where there are substantial grounds for believing that a person to be returned would be in danger of being tortured).

The word non-refoulement derives from the French refouler, which means to drive back or to repel. The idea that a State ought not to return persons to other States in certain circumstances is first referred to in article 3 of the 1933 Convention relating to the International Status of Refugees, under which the contracting parties undertook not to remove resident refugees or keep them from their territory, “by application of police measures, such as expulsions or non-admittance at the frontier (refoulement)”, unless dictated by national security or public order. Each State undertook, “in any case not to refuse entry to refugees at the frontiers of their countries of origin”.

The 1933 Convention was not widely ratified, but a new era began with the General Assembly’s 1946 endorsement of the principle that refugees with valid objections should not be compelled to return to their country of origin (see above, resolution 8 (I)). The Ad Hoc Committee on Statelessness and Related Problems initially proposed an absolute prohibition on refoulement, with no exceptions (United Nations Economic and Social Council, Summary Record of the twentieth meeting, Ad Hoc Committee on Statelessness and Related Problems, First Session, United Nations doc. E/AC.32/SR.20, (1950), 11-12, paras. 54 to 55). The 1951 Conference of Plenipotentiaries qualified the principle, however, by adding a paragraph to deny the benefit of non-refoulement to the refugee whom there are “reasonable grounds for regarding as a danger to the security of the country. or who, having been convicted by a final judgment of a particularly serious crime, constitutes a danger to the community of that country.” Apart from such limited situations of exception, however, the drafters of the 1951 Convention made it clear that refugees should not be returned, either to their country of origin or to other countries in which they would be at risk.

The Convention Standards of Treatment

States have also agreed to provide certain facilities to refugees, including administrative assistance (article 25); identity papers (article 27), and travel documents (article 28); the grant of permission to transfer assets (article 30); and the facilitation of naturalization (article 34).

Given the further objective of a solution (assimilation or integration), the Convention concept of refugee status thus offers a point of departure in considering the appropriate standard of treatment of refugees within the territory of Contracting States. It is at this point, where the Convention focuses on matters such as social security, rationing, access to employment and the liberal professions, that it betrays its essentially European origin; it is here, in the articles dealing with social and economic rights, that one still finds the greatest number of reservations, particularly among developing States.

The Convention proposes, as a minimum standard, that refugees should receive at least the treatment which is accorded to aliens generally. Most-favoured-nation treatment is called for in respect of the right of association (article 15), and the right to engage in wage-earning employment (article 17, paragraph 1). The latter is of major importance to the refugee in search of an effective solution, but it is also the provision which has attracted most reservations. Many States have emphasized that the reference to most-favoured-nation shall not be interpreted as entitling refugees to the benefit of special or regional customs, or economic or political agreements. Other States have expressly rejected most-favoured-nation treatment, limiting their obligation to accord only that standard applicable to aliens generally, while some view article 17 merely as a recommendation, or agree to apply it “so far as the law allows”.

“National treatment”, that is, treatment no different from that accorded to citizens, is to be granted in respect of a wide variety of matters, including the freedom to practice religion and as regards the religious education of children (article 4); the protection of artistic rights and industrial property (article 14); access to courts, legal assistance, and exemption from the requirement to give security for costs in court proceedings (article 16); rationing (article 20); elementary education (article 22, paragraph 1); public relief (article 23); labour legislation and social security (article 24, paragraph 1); and fiscal charges (article 29).

Article 26 of the Convention prescribes such freedom of movement for refugees as is accorded to aliens generally in the same circumstances. Eleven States have made reservations, eight of which expressly retain the right to designate places of residence, either generally, or on grounds of national security, public order (ordre public) or the public interest.

Reservations

While reservations are generally permitted under both the Convention and the Protocol, the integrity of certain articles is absolutely protected, including articles 1 (definition); 3 (non-discrimination); 4 (religion); 16, paragraph 1 (access to courts); and 33 (non-refoulement). Under the Convention, reservations are further prohibited with respect to articles 36 to 46, which include a provision entitling any party to a dispute to refer the matter to the International Court of Justice (article 38). The corresponding provision of the 1967 Protocol (article IV) may be the subject of reservation, and some have been made; to date (August 2008), however, no State has sought to make use of the dispute settlement procedure.

Cooperation with UNHCR

The General Assembly identified a protection role for the High Commissioner in relation, in particular, to international agreements on refugees. States party to the 1951 Convention/1967 Protocol have accepted specific obligations in this regard, agreeing to cooperate with the Office and in particular to “facilitate its duty of supervising the application of the provisions” of the Convention and Protocol (article 35 of the Convention; article II of the Protocol).

Treaty oversight mechanisms, such as those established under the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the 1984 United Nations Convention against Torture and the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child, have distinct roles, which may include both the review of national reports and the determination of individual or inter-State complaints. UNHCR does not possess these functions, and the precise nature of the obligation of States is not always clear, although together with the statutory role entrusted to UNHCR by the General Assembly, it is enough to give the Office a sufficient legal interest (locus standi) in relation to States’ implementation of their obligations under the Convention and Protocol. States generally do not appear to accept that UNHCR has the authority to lay down binding interpretations of these instruments, but it is arguable that the position of the UNHCR generally on the law or specifically on particular refugee problems requires to be considered in good faith.

In practice, States commonly associate UNHCR with their refugee decision-making, and UNHCR provides regular guidance on issues of interpretation. Its Handbook on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status, published in 1979 at the request of States members of the UNHCR Executive Committee, is regularly relied on as authoritative, if not binding, and more recent guidelines are also increasingly cited in refugee determination procedures.

The 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees

The origins of the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees, which reflected recognition by UNHCR and the States members of its Executive Committee that there was a disjuncture between the universal, unlimited UNHCR Statute and the scope of the 1951 Convention, were quite different from those of the latter. Instead of an international conference under the auspices of the United Nations, the issues were addressed at a colloquium of some thirteen legal experts which met in Bellagio, Italy, from 21 to 28 April 1965. The Colloquium did not favour a complete revision of the 1951 Convention, but opted instead for a Protocol by way of which States parties would agree to apply the relevant provisions of the Convention, but without necessarily becoming party to that treaty. The approach was approved by the UNHCR Executive Committee and the draft Protocol was referred to the Economic and Social Council for transmission to the General Assembly. The General Assembly took note of the Protocol (the General Assembly commonly “takes note” of, rather than adopts or approves, instruments drafted outside the United Nations system), and requested the Secretary-General to transmit the text to States with a view to enabling them to accede (resolution 2198 (XXI) of 16 December 1966). The Protocol required just six ratifications and it duly entered into force on 4 October 1967.

The Protocol is often referred to as “amending” the 1951 Convention, but in fact, and as noted above, it does no such thing. The Protocol is an independent instrument, not a revision within the meaning of article 45 of the Convention. States parties to the Protocol, which can be ratified or acceded to by a State without becoming a party to the Convention, simply agree to apply articles 2 to 34 of the Convention to refugees defined in article 1 thereof, as if the dateline were omitted (article I of the Protocol). As of August 2008, Cape Verde, Swaziland, the United States of America and Venezuela have acceded only to the Protocol, while Madagascar, Monaco, Namibia and St. Vincent & the Grenadines are party only to the Convention (and the Congo, Madagascar, Monaco, and Turkey have retained the geographical limitation).

Article II on the cooperation of national authorities with the United Nations is equivalent to article 35 of the Convention, while the few remaining articles (just eleven in all) add no substantive obligations to the Convention regime.

Evaluation

The Convention is sometimes portrayed today as a relic of the cold war and as inadequate in the face of “new” refugees from ethnic violence and gender-based persecution. It is also said to be insensitive to security concerns, particularly terrorism and organized crime, and even redundant, given the protection now due in principle to everyone under international human rights law.

The Convention does not deal with the question of admission, and neither does it oblige a State of refuge to accord asylum as such, or provide for the sharing of responsibilities (for example, by prescribing which State should deal with a claim to refugee status). The Convention also does not address the question of “causes” of flight, or make provision for prevention; its scope does not include internally displaced persons, and it is not concerned with the better management of international migration. At the regional level, and notwithstanding the 1967 Protocol, refugee movements have necessitated more focused responses, such as the 1969 OAU/AU Convention on the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa and the 1984 Cartagena Declaration; while in Europe, the development of protection doctrine under the 1950 European Convention on Human Rights has led to the adoption of provisions on “subsidiary” or “complementary” protection within the legal system of the European Union.

Nevertheless, within the context of the international refugee regime, which brings together States, UNHCR and other international organizations, the UNHCR Executive Committee, and non-governmental organizations, among others, the Convention continues to play an important part in the protection of refugees, in the promotion and provision of solutions for refugees, in ensuring the security of States, sharing responsibility, and generally promoting human rights. A Ministerial Meeting of States Parties, convened in Geneva in December 2001 by the Government of Switzerland to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the Convention, expressly acknowledged, “the continuing relevance and resilience of this international regime of rights and principles. ”.

In many States, judicial and administrative procedures for the determination of refugee status have established the necessary legal link between refugee status and protection, contributed to a broader and deeper understanding of key elements in the Convention refugee definition, and helped to consolidate the fundamental principle of non-refoulement. While initially concluded as an agreement between States on the treatment of refugees, the 1951 Convention has inspired both doctrine and practice in which the language of refugee rights is entirely appropriate.

It was no failure in 1951 not to have known precisely how the world would evolve; on the contrary, it may be counted a success that the drafters of the 1951 Convention were in fact able to identify, in the concept of a well-founded fear of persecution, the enduring, indeed universal, characteristics of the refugee, and to single out the essential, though never exclusive, reason for flight. That certainly has not changed, even if the scope and extent of the refugee definition have matured under the influence of human rights, and even as there is now increasing recognition of the need to enhance and ensure the protection of individuals still within their own country.

Related Materials

A.В Legal Instruments

Convention relating to the International Status of Refugees, Geneva, 28 October 1933,В League of Nations, В Treaty Series, vol. 159, p. 200.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, General Assembly resolution 217 (III) of 10 December 1948.

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, New York, 16 December 1966, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 999, p. 171.

African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, Nairobi, 27 June 1981, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1520, p. 217.

Cartagena Declaration on Refugees, Adopted by the Colloquium on the International Protection of Refugees in Central America, Mexico and Panama, Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, 22 November 1984.

Convention on the Rights of the Child, New York, 20 November 1989, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1577, p. 3.

B.В Documents

Report of the Ad Hoc Committee on Statelessness and Related Problems, Provisional draft of parts of the definition article of the preliminary draft convention relating to the status of refugees, prepared by the Working Group on this article (E/AC.32/L.6 and Corr. 1 and Rev.1, 23 January 1950).

Ad Hoc Committee on Statelessness and Related Problems, First Session, E/AC.32/SR.20, (1950), 11-12, paras. 54-55.

Handbook on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status under the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees HCR/IP/4/Eng/REV.1Reedited, Geneva, January 1992, UNHCR 1979.(See also the website of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees for other handbooks and guidelines: http://www.unhcr.org.)

Convention relating to the Status of Refugees

By resolution 248 B (IX) of 8 August 1949, the Economic and Social Council established the Ad Hoc Committee on Statelessness and Related Problems to consider the desirability of preparing a revised and consolidated convention relating to the international status of refugees and stateless persons and consider means of eliminating the problem. The Ad Hoc Committee, consisting of representatives of thirteen Governments, met from 16 January to 16 February 1950 and adopted a report containing the text of a draft Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and a Protocol thereto relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, with commentaries (E/1618 (E/AC.32/5) and Corr. 1).

By a note of 10 March 1950, the Secretary-General transmitted the report of the Ad Hoc Committee to Governments and invited their comments thereon, in order that these, together with the report, could be submitted to the eleventh session of the Economic and Social Council. (These comments are contained in documents E/1703 and Add. 1 to 7, and E/1704 and Corr.1 and 2.) В

The report of the Ad Hoc Committee and the comments received thereon were considered by the Social Committee of the Economic and Social Council from 31 July to 3 August and from 5 to 10 August 1950, and by the Council on 2 and 11 August 1950 (E/SR.399 and A/SR.406-407). The Social Committee discussed in detail the definition of the term “refugee” in the draft Convention, and considered and amended the draft Preamble. The draft definition and Preamble, as amended, were adopted by the Economic and Social Council on 11 August 1950. On the same date, the Council adopted resolution 319 B (XI), in which it took note of the report of the Ad Hoc Committee, of the draft agreements contained therein and of the comments received from Governments. It requested that the Secretary-General reconvene the Ad Hoc Committee to prepare revised drafts of the two instruments, taking into account the comments of Governments and of specialized agencies, and of discussions and decisions of the Economic and Social Council at its eleventh session, including the definition of the term “refugee” and the Preamble as approved by the Council.

On 14 December 1950, the General Assembly, considering the report of the Third Committee, adopted resolution 429 (V), by which it decided to convene a conference of plenipotentiaries in Geneva to complete the drafting of the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and the Protocol relating to the Status of Stateless Persons. The Assembly further recommended that the Governments participating in the conference take into consideration the draft Convention submitted by the Economic and Social Council and, in particular, the text of the definition of the term “refugees”, as contained in an annex to resolution 429 (V), which had been further amended by the Assembly prior to adopting the resolution (A/PV.325). The United Nations Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Status of Refugees and Stateless Persons met from 2 to 25 July 1951 and, on 25 July 1951, adopted the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (A/CONF.2/108/Rev.1).  The Convention entered into force on 22 April 1954, in accordance with its article 43, following the deposit of the sixth instrument of ratification.

Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees

In his annual report to the General Assembly at its twentieth session, in 1965, the High Commissioner for Refugees referred to a Colloquium on Legal Aspects of Refugee Problems, organized by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, during which the limitation of the personal scope of the Convention on the Status of Refugees had been discussed, including possible measures whereby the Convention might be extended to cover new refugee situations (A/6011/Rev.1, paras. 33 and 34). In 1966, the High Commissioner referred again to the question of a possible extension of the scope of the Convention (A/6311/Rev.1, para. 40) and, following consultations with States parties to the Convention and with members of the Executive Committee of the High Commissioner’s Programme, submitted the text of a draft Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees, removing the date limitation in the Convention and thereby extending its scope, to the Executive Committee at its sixteenth session (A/AC.96/346).

The Executive Committee took note of the draft Protocol and made certain modifications to the text. On the Committee’s recommendation, the High Commissioner submitted the draft Protocol, as modified, to the General Assembly of the United Nations, through the Economic and Social Council, as an addendum to his annual report (A/6311/Rev.1/Add.1).

The Economic and Social Council, in its resolution 1186 (XLI) of 18 November 1966, took note with approval of the draft Protocol (A/6303/Add.1) and transmitted the High Commissioner’s report to the General Assembly, which referred it to its Third (Social, Humanitarian and Cultural) Committee for consideration.

The Third Committee considered the draft Protocol, under the agenda entitled “Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees”, from 5 to 7 December 1966. On 7 December 1966, it adopted a draft resolution providing for approval of the Protocol (A/6586, draft resolution II).

The General Assembly considered the corresponding report of the Third Committee on 16 December 1966 and, by its resolution 2198 (XXI) of the same date, took note of the Protocol and requested the Secretary-General to transmit the text of the Protocol to the States mentioned in article V thereof, with a view to enabling them to accede to it (A/PV.1495). The authentic text of the Protocol was signed by the President of the General Assembly and the Secretary-General in New York on 31 January 1967, and transmitted to Governments. The Protocol entered into force on 4 October 1967, in accordance with its article VIII, on the day of deposit of the sixth instrument of accession.

Selected preparatory documents

(in chronological order)

Report of the Ad Hoc Committee on Statelessness and Related Problems containing the text of the draft Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and the Protocol thereto relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, including commentaries, 16 January to 16 February 1950 (E/1618 (E/AC.32/5) and Corr. 1)

Comments of Governments and Specialized Agencies on the report of the Ad Hoc Committee on Statelessness and Related Problems (E/1703 and Add. 1 to 7, and E/1704 and Corr.1 and 2)

Compilation of Comments of Governments and Specialized Agencies on the report of the Ad Hoc Committee on Statelessness and Related Problems, prepared by the Secretary-General (E/AC.32/L.40, 10 August 1950)

Economic and Social Council, Summary records of meeting Nos. 399 and 406 to 407, held, respectively, on 2 and 11 August 1950 (E/SR.399, 406-407)

Report of the Ad Hoc Committee on Refugees and Stateless Persons containing a revised draft Convention relating to the status of refugees and a draft Protocol relating to the status of stateless persons, 14 to 25 August 1950 (E/1850 and annex (E/AC.32/8 and annex))

Third Committee of the General Assembly, Summary records of meetings Nos. 324 to 330, 332, 334, 337 and 338, held, respectively, from 22 to 27 November, 29 to 30 November, and on 1, 4 and 6 December 1950 (A/C.3/SR.324-330, 332,334, 337, 338)

Third Committee of the General Assembly, Joint “compromise” amendments by the Informal Working Group relating to the definition of the term “refugee” (A/C.3/L.131/Rev.1)

Report of the Third Committee to the General Assembly (A/1682 and annex, 12 December 1950)

General Assembly, Verbatim records of plenary meeting No. 325, held on 14 December 1950 (A/PV.325)

General Assembly resolution 429 (V) of 14 December 1950 (Draft Convention relating to the Status of Refugees)

Final Act of the United Nations Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Status of Refugees and Stateless Persons, and Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, Geneva, 2 to 25 July 1951 (A/CONF.2/108/Rev.1)

For other records from the United Nations Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Status of Refugees and Stateless Persons and Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, see the official website of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees:

http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/refworld/rwmain.

Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees

Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to the General Assembly 1964/1965 (Official Records of the General Assembly, Twentieth Session, Supplement No. 11 (A/6011/Rev.1))

Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to the General Assembly 1965/1966 (Official Records of the General Assembly, Twenty-first Session, Supplement No. 11 (A/6311/Rev.1))

Text of the draft Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees prepared by the High Commissioner for Refugees, submitted to the Executive Committee on the High Commissioner’s Programme (A/AC.96/346, annex II)

Addendum to the report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to the General Assembly (1965/1966), containing the text of the draft Protocol (Official Records of the General Assembly, Twenty-first Session, Supplement No. 11A (A6311/Rev.1/Add.1))

Report of the Economic and Social Council to the General Assembly relating to its consideration of the draft Protocol (Official Records of the General Assembly, Twenty-first Session, Supplement No. 3A (A/6303/Add.1, chapter VI))

Economic and Social Council resolution 1186 (XLI) of 18 November 1966 (Annual report of the High Commissioner for Refugees: measures to extend the personal scope of the Convention of 28 July 1951 relating to the status of refugees) taking note of the draft Protocol and transmitting the report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to the General Assembly

Third (social, humanitarian and cultural) Committee, Summary records of meetings Nos. 1447 to 1450 held from 5 to 7 December 1966 (A/C.3/SR.1447-1450)

Report of the Third (social, humanitarian and cultural) Committee to the General Assembly (A/6586, 13 December 1966)

General Assembly, Verbatim records of plenary meeting No. 1495 held on 16 December 1966 (A/PV.1495)

The Convention relating to the Status of Refugees entered into force on 22 April 1954. For the current participation status of the Convention, as well as information and relevant texts of related treaty actions, such as reservations, declarations, objections, denunciations and notifications, see:

The Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees entered into force on 4 October 1967. For the current participation status of the Protocol, as well as information and relevant texts of related treaty actions, such as reservations, declarations, objections, denunciations and notifications, see:

| Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees | ||

| Economic and Social Council, 1453rd Meeting, 18 November 1966: Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees on measures to extend the personal scope of the Convention of 28 July 1951 relating to the status of refugees. Audio (22 minutes, Full version) | ||

| Statement by the President of the Economic and Social Council, Mr. Tewfik Bouattoura (Algeria) Introduction of the agenda item Audio (1 minute, Français) | ||

| Statement by Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Audio (5 minutes, English) | ||

| Statement by Mr. Donald MacDonald (Canada) Audio (1 minute, English) | ||

| Statement by Sir Edward Warner (United Kingdom) Audio (2 minutes, English) | ||

| Statement by Mr. Rahnema (Iran) Audio (1 minute, Français) | ||

| Statement by Mr. Djoudi (Algeria) Audio (1 minute, Français) | ||

| Statement by Mr. Le Diraison (France) Audio (1 minute, Français) | ||

| Statement by Mr. Ahmed (Pakistan) Audio (30 seconds, English) | ||

| Statement by Mr. Waldron-Ramsey (United Republic of Tanzania) Audio (6 minutes, English) | ||

| Statement by the President of the Economic and Social Council, Mr. Tewfik Bouattoura (Algeria) Decision to submit the report of the High Commissioner for Refugees to the General Assembly Audio (1 minute, Français) | ||

| Statement by Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Audio (1 minute, English) | ||

|  |  |  |

| 6 December 1966 Twenty-first Session of the General Assembly, meeting of the Third Committee on the Report of the High Commissioner for Refugees, United Nations Headquarters, New York [Read more] |

Twenty-first Session of the General Assembly, meeting of the Third Committee on the Report of the High Commissioner for Refugees,

United Nations Headquarters,

New York

[Read more]

Twenty-first Session of the General Assembly, meeting of the Third Committee on the Report of the High Commissioner for Refugees,

United Nations Headquarters,

New York

[Read more]

Twenty-first Session of the General Assembly, meeting of the Third Committee on the Report of the High Commissioner for Refugees,

United Nations Headquarters,

New York

[Read more]

Twenty-first Session of the General Assembly, meeting of the Third Committee on the Report of the High Commissioner for Refugees,

United Nations Headquarters,

New York

[Read more]

Twenty-first Session of the General Assembly, meeting of the Third Committee on the Report of the High Commissioner for Refugees,

United Nations Headquarters,

New York

[Read more]

Twenty-first Session of the General Assembly, meeting of the Third Committee on the Report of the High Commissioner for Refugees,

United Nations Headquarters,

New York

[Read more]

Twenty-first Session of the General Assembly, meeting of the Third Committee on the Report of the High Commissioner for Refugees,

United Nations Headquarters,

New York

[Read more]

Twenty-first Session of the General Assembly, meeting of the Third Committee on the Report of the High Commissioner for Refugees,

United Nations Headquarters,

New York

[Read more]

Twenty-first Session of the General Assembly, meeting of the Third Committee on the Report of the High Commissioner for Refugees,

United Nations Headquarters,

New York

[Read more]

Accession of Norway to the Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees,

United Nations Headquarters,

New York

[Read more]

Accession of Argentina to the Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees, United Nations Headquarters,

New York

[Read more]

Accession of the United States of America to the Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees, United Nations Headquarters,

New York

[Read more]

Accession of Ireland to the Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees,

United Nations Headquarters,

New York

[Read more]

Accession of Botswana to the Convention and Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees, United Nations Headquarters,

New York

[Read more]

Accession of the People’s Republic of the Congo to the Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees, United Nations Headquarters,

New York

[Read more]

Accession of Sudan to the Convention and Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees, United Nations Headquarters,

New York

[Read more]

Accession of Panama to the Convention and Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees, United Nations Headquarters,

New York

[Read more]

Accession of Colombia to the Convention and Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees, United Nations Headquarters,

New York

[Read more]

Accession of Bolivia to the Convention and Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees, United Nations Headquarters,

New York

[Read more]

Accession of the Philippines to the Convention and Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees, United Nations Headquarters,

New York

[Read more]

28 April 1983

Accession of El Salvador to the Convention and Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees, United Nations Headquarters,

New York

[Read more]

Codification Division, Office of Legal Affairs

Copyright В© United Nations, 2022. All Rights Reserved.

Terms and Conditions of Use.

Женевская конвенция о статусе беженцев

Женевская конвенция о статусе беженцев — конвенция (международный договор), принятая 28 июля 1951 года в Женеве конференцией полномочных представителей, созванной в соответствии с резолюцией 429 (V) Генеральной Ассамблеи ООН от 14 декабря 1950 года. Вступила в силу 22 апреля 1954 года.

Конвенция даёт определения понятия «беженец» и устанавливает общие основания, на которых должен быть предоставлен статус беженца. Конвенция запрещает какую-либо дискриминацию в отношении беженцев. Частью прав беженцы пользуются наравне с гражданами, частью — на тех же условиях, что и иностранцы. Конвенция допускает высылку беженца в интересах государственной безопасности.

Содержание

История

Предыстория

После падения Российской империи в 1917 году и развала Османской империи в 1923 году, Западную Европу заполонили беженцы из России и Турции.

30 сентября 1930 года Лига Наций создала Международную организацию по делам беженцев (Офис Нансена), которая не только продолжила работу Верховного Комиссара по делам русских и армянских беженцев, но также взяла на себя гуманитарную работу для беженцев, выполнявшуюся в 1924-1929 года Международной Организацией Труда.

В 1933 году был назначен Верховный Комиссар по делам беженцев из Германии. Так как Германия возражала против создания такого учреждения в рамках Лиги Наций, этот орган был создан заинтересованными государствами вне Лиги Наций. Только когда в 1936 году Германия покинула Лигу Наций, функции Верховного Комиссара по делам беженцев из Германии были интегрированы в Офис Нансена.

В июле 1938 года для того, чтобы справиться с возрастающим потоком беженцев из Германии, заинтересованные государства создали Межправительственный Комитет по Делам Беженцев. Этот Комитет работал вне Лиги Наций и занимался делами беженцев из Австрии и Испании. Комитет занимался защитой лишь нескольких групп беженцев: русских, армян, немцев, бежавших в Австрию, и людей, бежавших из Испании. Для этих групп были разработаны различные системы защиты. Понятия «определение статуса» тогда ещё не существовало.

В 1944 году в тесном сотрудничестве с Верховным Командованием Союзных Экспедиционных Сил было создано первое агентство ООН — Администрация ООН по оказанию помощи и реабилитации (UNRRA)

UNRRA была предшественницей УВКБ ООН. На тот момент в Европе насчитывалось 6 млн. человек, нуждающихся в помощи. По окончании войны 1 млн. человек из этих 6 отказались вернуться домой. Перед международным сообществом возникла ещё одна проблема.

В тесном сотрудничестве с Верховным Командованием Союзных Экспедиционных Сил работало первое агентство ООН, а именно Администрация ООН по оказанию Помощи и Реабилитации (UNRRA). Это агентство ООН было создано 9 ноября 1943 года, почти за два года до создания Организации Объединенных Наций17.

В 1945 году была создана ООН. 24 октября пятью постоянными членами Совета Безопасности и большинством других подписавших его государств был ратифицирован и вступил в силу Устав ООН. В нём много внимания уделялось правам человека и их защите.

Представители правительств в 1945-1946 гг. много говорили о проблеме беженцев, о том, что их нельзя возвращать домой против их воли. Проблема была признана международной.

10 декабря 1948 года была принята Всеобщая декларация прав человека. В ней среди прочего говорилось о праве на убежище. Однако Советский Союз и страны советского блока голосовали против принятия декларации, поскольку, по советской концепции, беженцы из стран Восточной Европы трактовались как предатели и их следовало возвращать на родину и судить. В то время в мире было 3 млн. беженцев.

В 1951 году в Женеве была принята ‘конвенция о статусе беженцев. Конвенция дала определения понятия «беженец» и устанавила общие основания, на которых должен быть предоставлен статус беженца. В документе была обозначена предельная дата действия — беженцем признавался человек, ставший таковым в результате событий, происшедших до 1 января 1951 года.

После 1951 года

31 января 1967 года Конвенция была дополнена принятым в Нью-Йорке Протоколом, касающимся статуса беженцев. Протокол подтвердил определение беженца, данное в Конвенции, за исключением слов «в результате событий, произошедших до 1 января 1951 года» и слов «в результате подобных событий». Протокол обязал государства-участников сотрудничать с Управлением Верховного комиссара ООН по делам беженцев.

Fact Sheet: International Refugee Protection System

What are the main international agreements requiring countries to protect refugees?

The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol. Together with other regional treaties and declarations, the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (1951 Convention) and its 1967 Protocol are the basis of the international protection system, addressing the rights of refugees.

The 1951 Convention, which was drafted after World War II, is the foundation of international refugee law that defined “refugee,” set principles preventing forced return of refugees to places where their lives or freedom would be threatened, and established the refugees’ and signing countries’ rights and responsibilities.

However, the 1951 Convention was originally focused on addressing refugee problems stemming from World War II. It defined a refugee as a person who faced persecution due to circumstances occurring before January 1, 1951, and allowed countries to limit the definition to circumstances that occurred only in Europe. With newly emerging refugee crises in the 1950s and early 1960s, countries adopted the 1967 Protocol, which is an independent but integrally-related document to the 1951 Convention that removed its time and geographic limits, applying the refugee definition to all eligible persons.

The 1951 Convention and 1967 Protocol also ensure protection of refugees against refoulement, or forcible return to a country where they face persecution, and provide them and their families with access to civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights similar to those enjoyed by nationals.

Which countries adopted the 1951 Convention and its 1967 Protocol?

76 percent of all countries. As of April 2015, 148 countries adopted both the 1951 Convention and its 1967 Protocol or just the 1967 Protocol. The United States adopted the 1967 Protocol on November 1, 1968, and after the Vietnam War, developed its own law, the Refugee Act of 1980, that included these documents’ refugee definition. There are 43 UN members that have not adopted the international laws, some of which host large refugee populations, such as Libya, Saudi Arabia, and India.

What are countries required to do under the 1951 Convention and 1967 Protocol?

Establish and maintain a national asylum system. While the signing countries to one or both of the documents agree to protect refugees, the laws require them to create or authorize competent national authorities to establish a framework for refugee protection in their countries. The authorities must decide on key national concepts and legal principles, determine which institutions will be responsible for refugee processing, monitor implementation of the national laws and gather relevant data to review impacts of their programs.

Who is a refugee under the 1951 Convention and its 1967 Protocol?

A person fleeing his or her home due to persecution, violence or war. International law defines refugee as an individual, who fears persecution, or has a well-founded fear or persecution, based on his or her race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. While the signing countries must adopt the definition of a refugee as stated in 1951 Convention and 1967 Protocol, individual countries may decide to further clarify the definition. For example, Australia’s law specifies kinds of persecution that qualify an applicant as a refugee.

Do the signing countries have special responsibilities towards certain categories of refugees?

Specifically, signing countries should protect:

Has the United States been criticized for failing to meet all its international commitments to protect refugees and asylum seekers?

Who organizes global refugee resettlement?

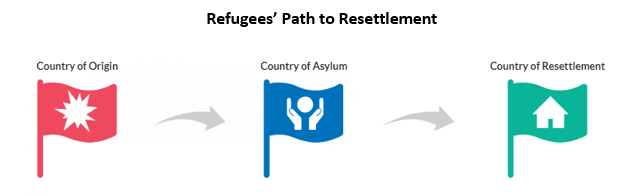

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and other international agencies. The UNHCR, which is a subsidiary organ of the United Nations General Assembly, oversees refugee resettlement, including selection and transfer of refugees from countries where they have sought protection (countries of asylum) to countries that have agreed to admit and provide them with permanent residency and eventually citizenship (countries of resettlement). UNHCR resettles only refugees who are outside of their home country or are stateless.

Source: https://rsq.unhcr.org/#_ga=2.252785801.1879793950.1552921343-2076042101.1546961494

The UNHCR conducts an initial screening and makes a Refugee Status Determination that an individual meets the definition of a refugee. These refugees are then referred to resettlement countries. Each country then conducts its own screenings based on its standards to decide which and how many refugees it will resettle.

UNHCR was established in in 1951 as an international organization providing protection to refugees together with other countries’ governments. Its Statute, which established UNHCR’s mandate and was adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1950, states that the organization shall be entirely non-political, humanitarian and social in character.

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) is another United Nation’s agency that provides assistance and protection specifically to Palestinian refugees, who are excluded from the 1951 Convention and its 1967 Protocol.

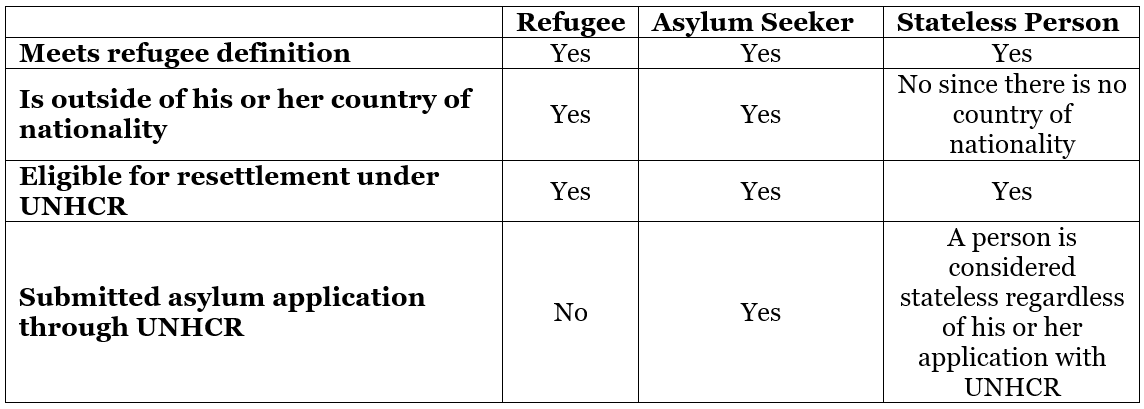

Who is eligible for resettlement by UNHCR?

Refugees, asylum seekers, and stateless persons. There are three group of people that UNHCR can assist:

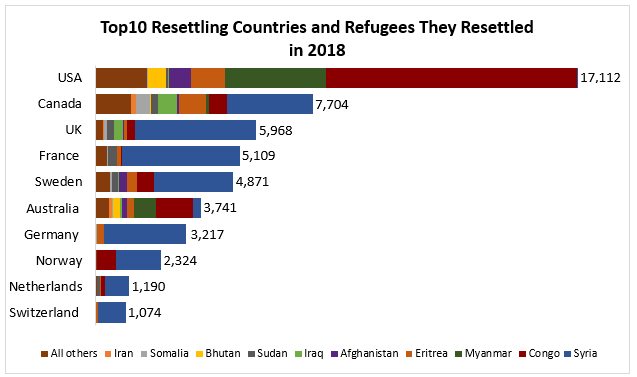

29 out of 46 resettlement countries in 2018. While 148 countries signed the 1951 Convention and/or 1967 Protocol, pledging to accept and protect refugees as they await their asylum application decisions, only 46 countries have agreed to resettle refugees, providing them with permanent status. The number of resettling countries worldwide has increased from 14 in 2005 to 46 in 2018, out of which just 29 actually resettled refugees.

How many refugees are resettled by UNHCR each year?

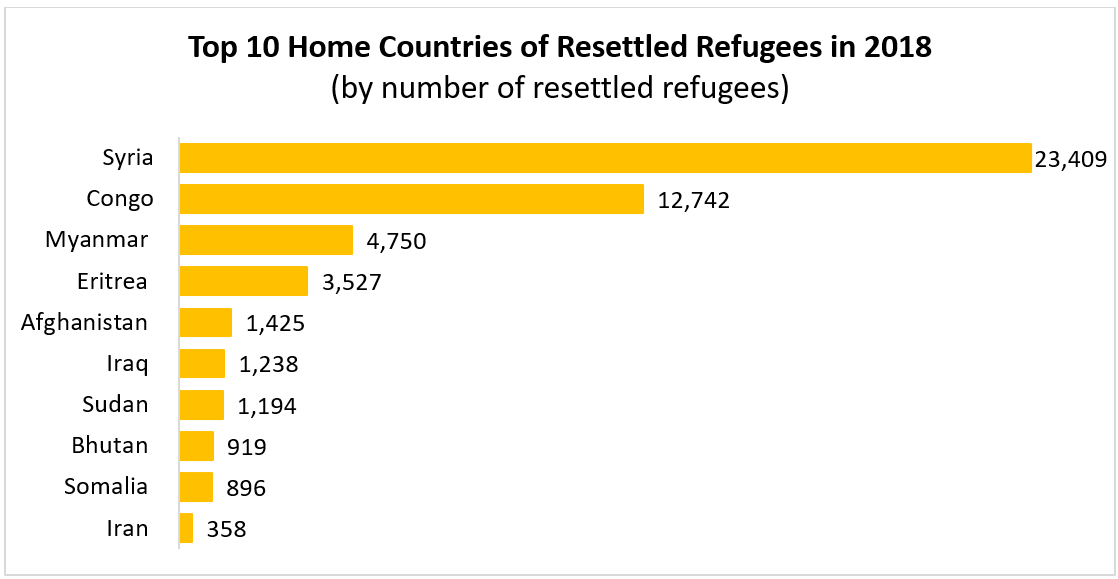

About 76,000 annually. Between 2009 and 2018, the resettling countries admitted an average of 76,000 refugees each year, with a peak of 126,000 in 2016 followed by a drop to a 10-year low of 55,700 in 2018. Even at the peak in 2016, the number of resettled refugees still accounted for less than one percent of the total refugee population worldwide. UNHCR mostly resettled refugees from Syria, Congo and Myanmar in 2018.

Source: https://rsq.unhcr.org/en/#oF8j

Source: https://rsq.unhcr.org/en/#coF2

How many refugees and asylum seekers exist?

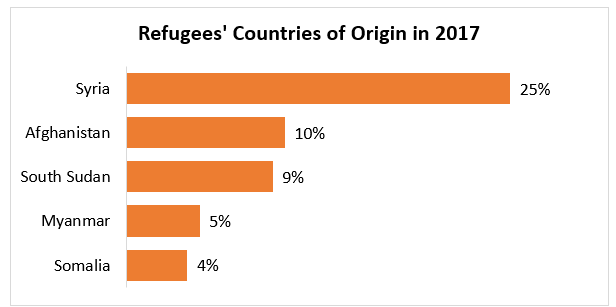

Over 25 million refugees and 3 million asylum seekers existed worldwide in 2017. In 2017, there were 25.4 million refugees worldwide and 3.1 million asylum seekers. That number of refugees is a 2.9-million increase from 2016, which is the biggest increase UNHCR has ever recorded in a single year. Overall, a record 68.5 million people were forcibly displaced around the world by the end of 2017.

Where do refugees come from?

Mostly from Syria, Afghanistan, South Sudan. In 2017, more than a half of all refugees worldwide were from five countries:

Source: https://www.unhcr.org/globaltrends2017/Source: https://www.unhcr.org/globaltrends2017/

Which asylum countries currently host the largest number of refugees?

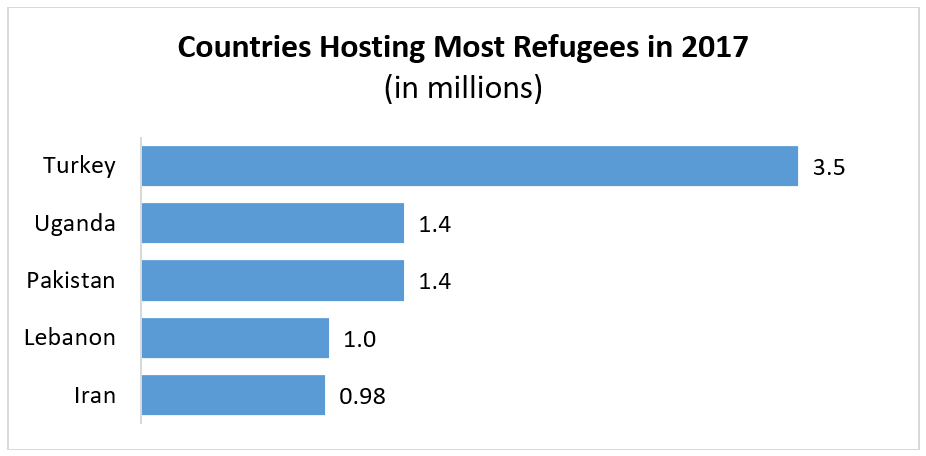

Mostly Turkey, Uganda and Pakistan. In 2017, the top asylum countries worldwide that hosted refugees were:

Who are internally displaced people?

Individuals, who left their homes but are still in their home country. Internally Displaced People (IDPs) are individuals, who left their homes but did not cross the border and seek safety in other towns, communities, camps, forests, and etc. in their country. IDPs account for the largest share of all forcibly displaced people worldwide, about 40 million people in total. IDPs are not protected by the international protection laws because they are still protected by their governments. Colombia, Syria, Somalia and Democratic Republic of Congo have some largest numbers of IDPs in the world.