What is the london underground called

What is the london underground called

The London Underground

London’s underground railway network. Article foe senior couples and mature solo travellers joining a small group tour interested in learning about Victorian London and the evolution of the Tube network in the Industrial revolution.

4 Oct 21 В· 8 mins read

The London Underground

Beneath London is another London, a shadowy counterpart still not mapped in its entirety, but in many ways similar to the London above the ground. According to Peter Ackroyd in London Under (Vintage, 2012), “It was said of the Victorian Londoner, wrapped in fog and darkness, that he or she would not know the difference between the two worlds”. Beneath Piccadilly Circus, for example, is an underground station also called Piccadilly Circus, and the roads “that converge…on Islington, have their counterparts beneath the surface” (p.2). London’s extensive subterranean transport system snakes 400 kilometres long beneath the ground, and in this post we will explore its history, and see what’s in store for the world’s oldest underground railway system.

Building the Railways

London is based upon clay formed more than fifty million years ago (Ackroyd, 2012, p.9). In the year 43, it was the Roman settlement of Londinium. The Romans’ bridge over the River Thames turned the city into a major commercial centre in Roman Britain until the 5th century, and the defensive London Wall defined the city borders for centuries.

London’s ancient past continue to appear in the modern metropolis. Though dismantled in the 1700s, sections of the London Wall remain visible, snaking through private and public establishments in the city, and archaeologists continue to find skeletons dating back to Roman times.

Save for a period after the collapse of Roman rule and the era of numerous Viking raids, London has always been a busy, bustling city. Around the 1800s, with the advent of the Industrial Revolution marked by mass migration from the countryside to urban areas, London was already feeling the weight of its increasing population. The city’s population exploded to more than six million people in the 19th century. Roads were congested with horse-drawn omnibuses and carriages (p. 113), and even the Thames became overcrowded, causing damage to merchandise as the transport of goods across the river got delayed.

Charles Pearson, solicitor to the City of London, first proposed the idea of an underground railway system in the 1830s to ease above-ground congestion, envisioning a route that connected King’s Cross with Farringdon Street. The plan was met with derision, driven by fears of the underground turning into a refuge for Fenians (members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood) who might blow up the city (p. 113).

Thames Tunnel

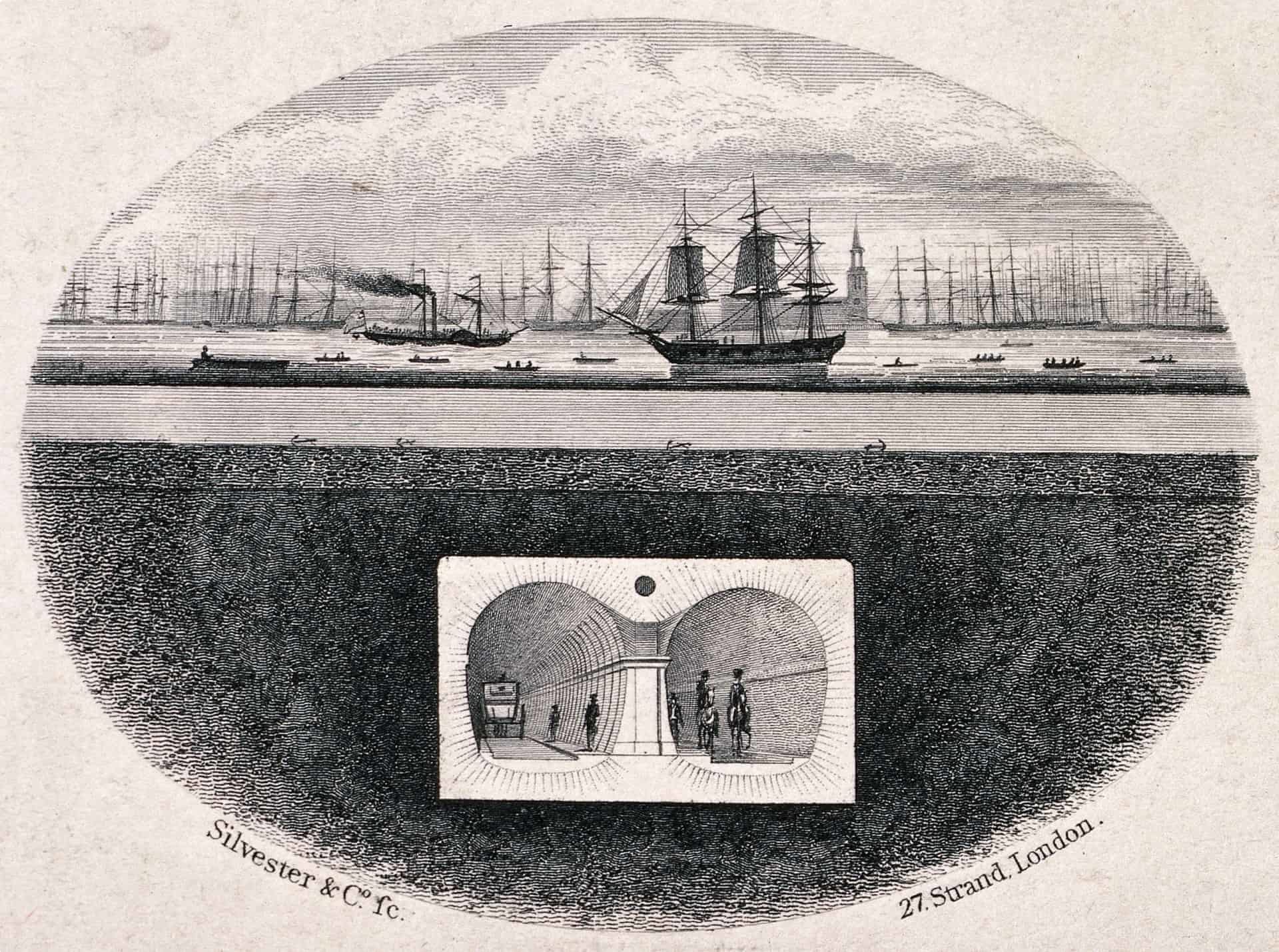

Years before Pearson’s proposal, Marc Isambard Brunel, a French naval officer who settled in England, designed and patented the tunnelling shield, a machine for driving tunnels in soft ground, which could be used to bore tunnels under rivers. Brunel’s invention became an important tool of modern civil engineering.

His most famous achievement was the construction of the Thames Tunnel, built with the help of his son (and later famous English engineer) Isambard Kingdom Brunel. The Thames Tunnel, opened in 1843, was the world’s first tunnel built beneath a river. It was originally planned to convey cargo and ease the congestion on the Thames, but lack of sufficient funding and accidents turned it into a pedestrian attraction, welcoming 50,000 curious visitors on the first day. A successful attraction for sure, but a structure not fulfilling its intended purpose.

According to Matthew Wills, Nathaniel Hawthorne went through the tunnel in 1855 and imagined it “choked up with mud, its precise locality unknown, and nothing…left of it but an obscure tradition.” Pearson’s detractors believed an underground railway would just have the same fate as the Thames Tunnel.

The Met

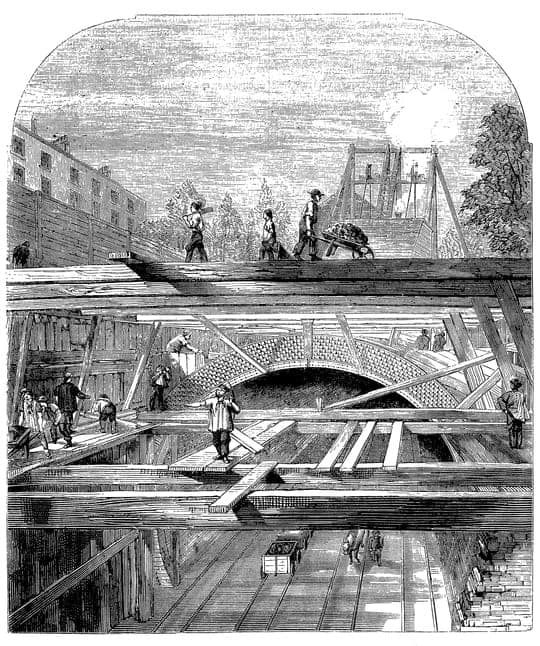

But Pearson persisted, and though work on the railway was delayed by funding concerns and the Crimean War, construction finally began in 1860 using the conventional “cut-and-cover” method–that is, excavating trenches, building the structure, and covering it back up. The resulting Metropolitan Underground Railway (or the Met) opened on January 10, 1863.

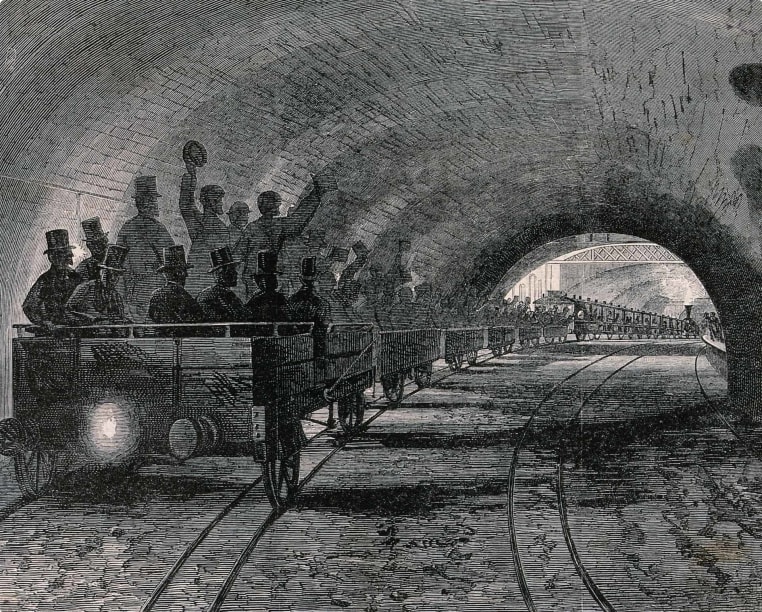

As steam locomotives were used to haul the wooden carriages on the line, the tunnel quickly filled with sulphurous fumes. This, however, did not stop passengers from taking the subterranean trains between Paddington (then called Bishop’s Road) and Farringdon Street, attracted by the spectacle of riding the first-ever underground railway in the world.

The Met carried nearly 10 million passengers in its first year and 12 million in its second year–a roaring success. It would be greatly extended in the following years, branching out to other lines and giving birth to the “Tube”, or the London Underground network.

Deeper Underground

Money from tourists visiting the Thames Tunnel helped continue its development, and in 1869, the first cargo steam train travelled beneath the River Thames, ensuring that Hawthorne’s fears of a forgotten and unused tunnel “choked up with mud” would not come to pass.

The Met’s success led to other railway companies petitioning Parliament for licenses to build new underground railways. The original line was expanded on either end and reached Hammersmith (1864), Richmond (1877), and closed a loop called the Inner Circle line in central London (1884), the Met connecting the rails with a rival company, the District Railway Company. The Inner Circle line became very busy, with over 800 trains running around all or part of the line every day.

The railways made the city feel smaller, with every spot accessible, allowing lower-middle-class professionals to continue living in the safe but relatively inexpensive (at least compared to central London) suburbs and still work in the city. At times, the train itself caused the suburbs to form on its path (nicknamed the “Metroland” suburbs), as what happened in the Middlesex countryside when the Met railway made its way through there from a branch at Baker Street. Train tracks even made it as far as Verney Junction, more than 80 kilometres from central London.

These railways were built using the “cut and cover” method, but a new tunnelling shield developed by J.H. Greathead allowed construction to go deeper. In 1866, the City of London and Southwark Subway Company (later called the City and South London Railway) began work on tunnels deep beneath the earth, which allowed them to work without snarling traffic and interfering with building foundations. The tunnels ran from King William Street to Stockwell in South London (Ackroyd, 2012, p. 120) and became known as the Tube, a nickname used for the first time then and which had been used ever since.

Railways Go Electric

The deep-level line was opened to the public in 1890, and the trains that travelled here were the first to be powered by electricity, hence making the line the first underground electric railway in the world. The full journey from Stockwell to the city took only 18 minutes. As the trains no longer burned coal, there were no noxious fumes emitted, making travel more comfortable. What caused outrage was the fact that the line introduced no demarcation of classes. The older trains had three different classes, with tickets costing three, four and six pence for a single journey. Now on the Stockwell line every carriage looked the same, and tickets were simply charged a uniform fare of twopence. Ackroyd writes that “the Railway Times complained that lords and ladies would now be travelling with Billingsgate fishwives and Smithfield porters.”

In 1900, American railway magnate Charles Tyson Yerkes led the construction of more tubes and the electrification of the old lines. The use of electricity also accelerated development, as there would be no need for vents to let out smoke, and the trains could even travel on top of one another.

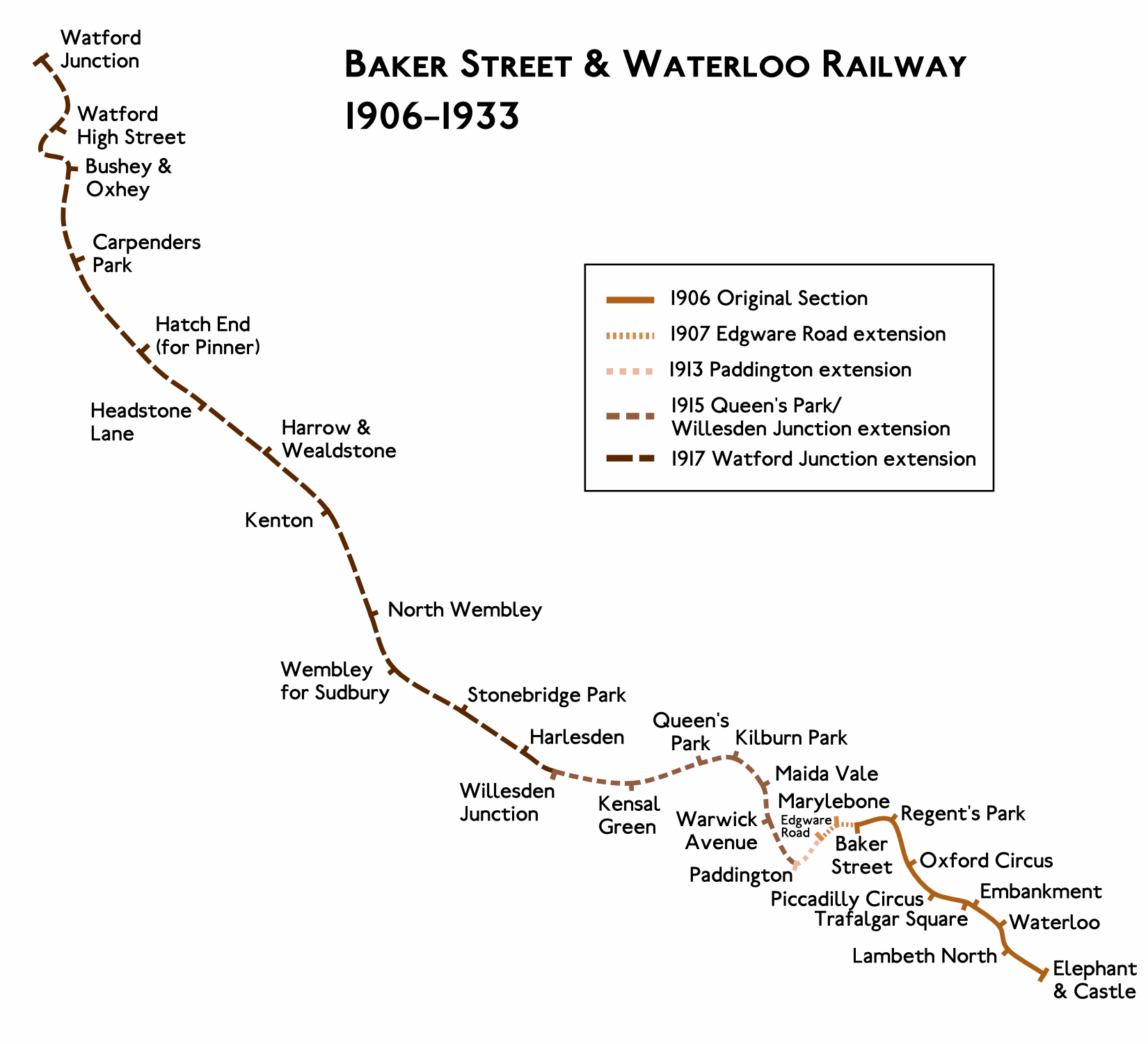

Yerkes formed the Underground Electric Railways Company of London Limited (UERL), which served as the holding company for the three tube lines opened in 1906 and 1907: the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway, the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway, and the Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway. It also served as the parent company of the District Railway, which UERL electrified between 1903 and 1905.

In 1908, the word “Underground” first appeared in Tube stations, accompanied by the now world-famous red-circle logo. Developments continued with the introduction of the first electric ticket machine (1908), first escalators (1911), and with air-operated doors replacing doors operated by hand (1929). During the two world wars, the Underground served as shelters (for both people and valuable items retrieved from the British Museum) from the bombings, and as mini-factories for munitions and war offices.

London’s Abandoned Tunnels

These rapid developments underground were marked by false starts, project pivots, and eventual abandonment and closures of many tube lines. Franklin Jarrier drew a map of these 49 “ghost stations”, including St. Mary’s station, which was bombed in World War II and closed in 1938; the reportedly unnecessary Brompton Road Underground station, closed in 1934; and York Road station, closed in 1932 due to low passenger volumes. Low passenger volumes also led to the closure of Blake Hall on the Central Line in 1981; when it closed it only served 17 passengers per day.

The London Transport Museum offers a guided tour called Hidden London, where experienced guides take interested visitors through London’s disused stations and secret sites. Stops include the abandoned spaces of Charing Cross Underground beneath Trafalgar Square, closed in 1999 and now used as film sets for blockbusters such as Skyfall, and the tunnels of Euston Station, which still had fragments of vintage advertising posters clinging to its walls, a gallery hidden for more than 50 years.

Another interesting stop is Down Street, a working station from 1907 to 1932, before it was converted into the Railway Executive Committee’s headquarters. This was where Prime Minister Winston Churchill took refuge at the height of the Blitz.

Modern Developments

The Underground was funded entirely by private companies until 1933, when the railways, tramways, buses and coaches were integrated into a quasi-public organisation, the London Passenger Transport Board, formed in response to the unregulated small bus operators plying the streets and affecting the profitability of the road transport network.

That same year, a map of the Underground designed by Harry Beck was distributed to the public. Before Beck, the maps of the Tubes were geographical in nature and difficult to read. Beck based his design on an electrical circuit, an elegant diagram that was easy on the eyes and which could be easily followed by passengers. You can see the the newest map of the Tubes here.

In 1948, London Transport was nationalised and placed under the British Transport Commission, and later directly below the Minister of Transport as the London Transport Board in 1962. The Underground saw the addition of a new line for the first time in half a century: the Victoria Line, opened in 1968.

Control of the railways was moved from central to local government in 1970, and the Jubilee Line was opened in 1979, named in honour of Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee. In 2007, the London Underground, with a history of many firsts, reached another landmark: it was the first time that one billion passengers used it within just one year.

Today, the London Underground is run by Transport for London, a local government body, while projects to upgrade the lines are awarded to private companies. The next project to expand the Underground is the construction of the new “Elizabeth Line” (being built by Crossrail Limited), Europe’s biggest (and most expensive) underground construction project. The Elizabeth Line, the Tube’s first new line in 50 years, is envisioned to connect stations such as Paddington to Canary Wharf in only 17 minutes. It is expected to be fully operational by 2020.

If you want to learn more about the London Underground, do refer to Peter Ackroyd’s London Under, particularly the chapters “Darkness Visible” and “The Deep Lines”, which were used as references for this article. Other resources are linked throughout the post.

To know more about the railways of Britain, consider joining Odyssey Traveller’s Exploring Britain through its Canals and Railways tour where we visit the key sites associated with the history of the railway and canal systems. We travel from the midlands of England and North Wales, up the west coast to Scotland, before returning down the east coast to London. Our small group tours include an experienced guide to provide context and access to locations off the beaten track.

Odyssey Traveller also runs a tour focused on Britain and the Industrial Revolution, the Queen Victoria’s Great Britain tour. This 21-day small group program provides participants with talks and short lectures from a group of guides with expertise on Victorian Britain. The tour commences in London and concludes in Glasgow.

For more information on all of Odyssey Traveller’s tours to the British Isles, please click here.

London Underground

London Underground Victoria Line 2009 Stock Observations

London Underground Victoria Line 2009 Stock Observations.

The earlier lines of the present London Underground network, which were built by various private companies, became part of an integrated transport system (which excluded the main line railways) in 1933 with the creation of the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB), more commonly known by its shortened name: «London Transport». The underground network became a single entity when London Underground Limited (LUL) was formed by the UK government in 1985. Since 2003 LUL has been a wholly owned subsidiary of Transport for London (TfL), the statutory corporation responsible for most aspects of the transport system in Greater London, which is run by a board and a commissioner appointed by the Mayor of London.

The Underground has 275 stations and approximately 400 km (250 miles) of track, making it the longest metro system in the world by route length, and one of the most served in terms of stations. In 2007, over one billion passenger journeys were recorded.

Contents

History [ ]

History Of London Underground-0

History Of London Underground. Documentary about the history of the London Underground.

Railway construction in the United Kingdom began in the early 19th century. By 1854 six separate railway terminals had been built just outside the centre of London: London Bridge, Euston, Paddington, King’s Cross, Bishopsgate and Waterloo. At this point, only Fenchurch Street Station was located in the actual City of London. Traffic congestion in the city and the surrounding areas had increased significantly in this period, partly due to the need for rail travellers to complete their journeys into the city centre by road. The idea of building an underground railway to link the City of London with the mainline terminals had first been proposed in the 1830s, but it was not until the 1850s that the idea was taken seriously as a solution to the traffic congestion problems.

The first underground railways [ ]

In 1854 an Act of Parliament was passed approving the construction of an underground railway between Paddington Station and Farringdon Street via King’s Cross which was to be called the Metropolitan Railway. The Great Western Railway (GWR) gave financial backing to the project when it was agreed that a junction would be built linking the underground railway with their mainline terminus at Paddington. GWR also agreed to design special trains for the new subterranean railway.

Construction was delayed for several years due to a shortage of funds. The fact that this project got under way at all was largely due to the lobbying of Charles Pearson, who was Solicitor to the City of London Corporation at the time. Pearson had supported the idea of an underground railway in London for several years. He advocated plans for the demolition of the unhygienic slums which would be replaced by new accommodation for their inhabitants in the suburbs, with the new railway providing transportation to their places of work in the city centre. Although he was never directly involved in the running of the Metropolitan Railway, he is widely credited as being one of the first true visionaries behind the concept of underground railways. And in 1859 it was Pearson who persuaded the City of London Corporation to help fund the scheme. Work finally began in February 1860, under the guidance of chief engineer John Fowler. Pearson died before the work was completed.

The Metropolitan Railway opened on 10 January 1863. Within a few months of opening it was carrying over 26,000 passengers a day. The Hammersmith and City Railway was opened on 13 June 1864 between Hammersmith and Paddington. Services were initially operated by GWR between Hammersmith and Farringdon Street. By April 1865 the Metropolitan had taken over the service. On 23 December 1865 the Metropolitan’s eastern extension to Moorgate Street opened. Later in the decade other branches were opened to Swiss Cottage, South Kensington and Addison Road, Kensington (now known as Kensington Olympia). The railway had initially been dual gauge, allowing for the use of GWR’s signature broad gauge rolling stock and the more widely used standard gauge stock. Disagreements with GWR had forced the Metropolitan to switch to standard gauge in 1863 after GWR withdrew all its stock from the railway. These differences were later patched up, however broad gauge was totally withdrawn from the railway in March 1869.

On 24 December 1868, the Metropolitan District Railway began operating services between South Kensington and Westminster using Metropolitan Railway trains and carriages. The company, which soon became known as «the District», was first incorporated in 1864 to complete an Inner Circle railway around London in conjunction with the Metropolitan. This was part of a plan to build both an Inner Circle line and Outer Circle line around London.

The Metropolitan and the District were initially friendly to each other. They shared four directors and the two companies were widely expected to merge once the Inner Circle was completed. However a fierce rivalry soon developed when the independent directors on the District board became dissatisfied with the performance of the Metropolitan service providers. On 3 January 1870 the Metropolitan informed the District that operating agreements would cease in 18 months. The four Metropolitan directors serving on the District board subsequently resigned. This severely delayed the completion of the Inner Circle project as the two companies competed to build far more financially lucrative railways in the suburbs of London. The London and North Western Railway (LNWR) began running their Outer Circle service from Broad Street via Willesden Junction, Addison Road and Earl’s Court to Mansion House in 1872. The Inner Circle was not completed until 1884, with the Metropolitan and the District jointly running services. In the meantime, the District had finished its route between West Brompton and Blackfriars in 1870, with an interchange with the Metropolitan at South Kensington. In 1877, it began running its own services from Hammersmith to Richmond, on a line which had originally opened by the London & South Western Railway (LSWR) in 1869. The District then opened a new line from Turnham Green to Ealing in 1879 and extended its West Brompton branch to Fulham in 1880. Over the same decade the Metropolitan was extended to Harrow in the north-west.

The early tunnels were dug mainly using cut-and-cover construction methods. This caused widespread disruption and required the demolition of several properties on the surface. The first trains were steam-hauled, which required effective ventilation to the surface. Ventilation shafts at various points on the route allowed the engines to expel steam and bring fresh air into the tunnels. One such vent is at Leinster Gardens, W2. In order to preserve the visual characteristics in what is still a well-to-do street, a five-foot-thick (1.5 m) concrete façade was constructed to resemble a genuine house frontage.

On 7 December 1869 the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LB&SCR) started operating a service between Wapping and New Cross Gate on the East London Railway (ELR) using the Thames Tunnel designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel. This had opened in 1843 as a pedestrian tunnel, but in 1865 it was purchased by the ELR (a consortium of six railway companies: the Great Eastern Railway (GER); London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LB&SCR); London, Chatham and Dover Railway (LCDR); South Eastern Railway (SER); Metropolitan Railway; and the Metropolitan District Railway) and converted into a railway tunnel. In 1884 the District and the Metropolitan began to operate services on the line.

By the end of the 1880s, underground railways reached Chesham on the Metropolitan, Hounslow, Wimbledon and Whitechapel on the District and New Cross on the East London Railway. By the end of the 19th century, the Metropolitan had extended its lines far outside of London to Aylesbury, Verney Junction and Brill, creating new suburbs along the route—later publicised by the company as Metro-land. Right up until the 1930s the company maintained ambitions to be considered as a main line rather than an urban railway.

The first tube lines [ ]

Geographic route map of the Baker Street & Waterloo Railway (1906-1933).

The first underground railways, excluding the ELR, had been just 10 feet deep. Following advances in the use of tunnelling shields, electric traction and deep-level tunnel designs, later railways were built even further underground. This caused much less disruption at ground level and it was therefore cheaper and preferable to the cut-and-cover construction method.

The City & South London Railway (C&SLR, now part of the Northern Line) opened in 1890, between Stockwell and the now closed original terminus at King William Street. It was the first «deep-level» electrically operated railway in the world. By 1900 it had been extended at both ends, to Clapham Common in the south and Moorgate Street (via a diversion) in the north. The second such railway, the Waterloo and City Railway, opened in 1898. It was built and run by the London and South Western Railway.

On 30 July 1900 the Central London Railway (now known as the Central Line) was opened, operating services from Bank to Shepherd’s Bush. It was nicknamed the «Twopenny Tube» for its flat fare and cylindrical tunnels; the «tube» nickname was eventually transferred to the Underground system as a whole. An interchange with the C&SLR was provided at Bank. Construction had also begun in August 1898 on the Baker Street & Waterloo Railway. However work on this railway came to a halt 18 months after it began when funds ran out.

Integration [ ]

In the early 20th century the presence of six independent operators running different Underground lines caused passengers substantial inconvenience; in many places passengers had to walk some distance above ground to change between lines. The costs associated with running such a system were also heavy, and as a result many companies looked to financiers who could give them the money they needed to expand into the lucrative suburbs as well as electrify the earlier steam operated lines. The most prominent of these was Charles Yerkes, an American tycoon who secured the right to build the Charing Cross, Euston & Hampstead Railway (CCE&HR) on 1 October 1900. In March 1901 he effectively took control of the District and this enabled him to form the Metropolitan District Electric Traction Company (MDET) on 15 July. Through this he acquired the Great Northern & Strand Railway and the Brompton & Piccadilly Circus Railway in September 1901, the construction of which had already been authorised by Parliament, together with the moribund Baker Street & Waterloo Railway in March 1902. On 9 April the MDET evolved into the Underground Electric Railways of London Company Ltd (UERL). The UERL also owned three tramway companies and went on to buy the London General Omnibus Company, creating an organisation colloquially known as «the Combine» which went on to dominate underground railway construction in London until the 1930s.

Independent ventures did continue in the early part of the 20th century. The independent Great Northern & City Railway opened in 1904 between Finsbury Park and Moorgate. It was the only tube line of sufficient diameter to be capable of handling main line stock, and it was originally intended to be part of a main line railway. However money soon ran out and the route remained separate from the main line network until the 1970s. The C&SLR was also extended northwards to Euston by 1907.

In early 1908, in an effort to increase passenger numbers, the underground railway operators agreed to promote their services jointly as «the Underground», publishing new adverts and creating a free publicity map of the network for the purpose. The map featured a key labelling the Bakerloo Railway, the Central London Railway, the City & South London Railway, the District Railway, the Great Northern & City Railway, the Hampstead Railway (the shortened name of the CCE&HR), the Metropolitan Railway and the Piccadilly Railway. Some other railways appeared on the map but with less prominence than the aforementioned lines. These included part of the ELR (although the map wasn’t big enough to fit in the whole line) and the Waterloo and City Railway. As the latter was owned by a main line railway company it wasn’t included in this early phase of integration. As part of the process, «The Underground» name appeared on stations for the first time and electric ticket-issuing machines were also introduced. This was followed in 1913 by the first appearance of the famous circle and horizontal bar symbol, known as «the roundel», designed by Edward Johnston.

On 1 January 1913 the UERL absorbed two other independent tube lines, the C&SLR and the Central London Railway. As the Combine expanded, only the Metropolitan stayed away from this process of integration, retaining its ambition to be considered as a main line railway. Proposals were put forward for a merger between the two companies in 1913 but the plan was rejected by the Metropolitan. In the same year the company asserted its independence by buying out the cash strapped Great Northern and City Railway. It also sought a character of its own. The Metropolitan Surplus Lands Committee had been formed in 1887 to develop accommodation alongside the railway and in 1919 Metropolitan Railway Country Estates Ltd. was founded to capitalise on the post-World War One demand for housing. This ensured that the Metropolitan would retain an independent image until the creation of London Transport in 1933.

The Metropolitan also sought to electrify its lines. The District and the Metropolitan had agreed to use the low voltage dc system for the Inner Circle, comprising two electric rails to power the trains, back in 1901. At the start of 1905 electric trains began to work the Uxbridge branch and from 1 November 1906 electric locomotives took trains as far as Wembley Park where steam trains took over. This changeover point was moved to Harrow on 19 July 1908. The Hammersmith & City branch had also been upgraded to electric working on 5 November 1906. The electrification of the ELR followed on 31 March 1913, the same year as the opening of its extension to Whitechapel and Shoreditch. Following the Grouping Act of 1921, which merged all the cash strapped main line railways into four companies (thus obliterating the original consortium that had built the ELR), the Metropolitan agreed to run passenger services on the line.

The Bakerloo line extension to Queen’s Park was completed in 1915, and the service extended to Watford Junction via the London and North Western Railway tracks in 1917. The extension of the Central line to Ealing Broadway was delayed by the war until 1920.

The major development of the 1920s was the integration of the CCE&HR and the C&SLR and extensions to form what was to become the Northern line. This necessitated enlargement of the older parts of the C&SLR, which had been built on a modest scale. The integration required temporary closures during 1922—24. The Golders Green branch was extended to Edgware in 1924, and the southern end was extended to Morden in 1926.

The Watford branch of the Metropolitan opened in 1925 and in the same year electrification was extended to Rickmansworth. The last major work completed by the Metropolitan was the branch to Stanmore which opened in 1932.

By 1933 the Combine had completed the Cockfosters branch of the Piccadilly Line, with through services running (via realigned tracks between Hammersmith and Acton Town) to Hounslow West and Uxbridge.

London Transport [ ]

In 1933 the Combine, the Metropolitan and all the municipal and independent bus and tram undertakings were merged into the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB), a self-supporting and unsubsidised public corporation which came into being on 1 July 1933. The LPTB soon became known as «London Transport» (LT).

Shortly after it was created, LT began the process of integrating the underground railways of London into one network. All the separate railways were given new names in order to become lines within it. A free map of these lines, designed by Harry Beck, was issued in 1933. It featured the District Line, the Bakerloo Line, the Piccadilly Line, the Edgware, Highgate and Morden Line, the Metropolitan Line, the Great Northern & City Line, the East London Line and the Central London Line. Commonly regarded as a design classic, an updated version of this map is still in use today. The Waterloo & City line was not included in this map as it was still owned by a main line railway (the Southern Railway since 1923) and not LT.

LT announced a scheme for the expansion and modernisation of the network entitled the New Works Programme, which had followed the announcement of improvement proposals for the Metropolitan Line. This consisted of plans to extend some lines, to take over the operation of others from main-line railway companies, and to electrify the entire network. During the 1930s and 1940s, several sections of main-line railways were converted into surface lines of the Underground system. The oldest part of today’s Underground network is the Central line between Leyton and Loughton, which opened as a railway seven years before the Underground itself.

LT also sought to abandon routes which made a significant financial loss. Soon after the LPTB started operating, services to Verney Junction and Brill on the Metropolitan Railway were stopped. The renamed «Metropolitan Line» terminus was moved to Aylesbury.

The outbreak of World War II delayed all the expansion schemes. From mid-1940, the Blitz led to the use of many Underground stations as shelters during air raids and overnight. The authorities initially tried to discourage and prevent this, but later supplied bunks, latrines, and catering facilities. Later in the war, eight London deep-level shelters were constructed under stations, ostensibly to be used as shelters (each deep-level shelter could hold 8,000 people) though plans were in place to convert them for a new express line parallel to the Northern line after the war. Some stations (now mostly disused) were converted into government offices: for example, Down Street was used for the headquarters of the Railway Executive Committee and was also used for meetings of the War Cabinet before the Cabinet War Rooms were completed; Brompton Road was used as a control room for anti-aircraft guns and the remains of the surface building are still used by London’s University Royal Naval Unit (URNU) and University London Air Squadron (ULAS).

After the war one of the last acts of the LPTB was to give the go-ahead for the completion of the postponed Central Line extensions. The western extension to West Ruislip was completed in 1948, and the eastern extension to Epping in 1949; the single-line branch from Epping to Ongar was taken over and electrified in 1957.

Nationalisation [ ]

On 1 January 1948 London Transport was nationalised by the incumbent Labour government, together with the four remaining main line railway companies, and incorporated into the operations of the British Transport Commission (BTC). The LPTB was replaced by the London Transport Executive (LTE). This brought the Underground under the remit of central government for the first time in its history.

The implementation of nationalised railways was a move of necessity as well as ideology. The main line railways had struggled to cope with a war economy in the First World War and by the end of World War Two the four remaining companies were on the verge of bankruptcy. Nationalisation was the easiest way to save the railways in the short term and provide money to fix war time damage. However the BTC prioritised the reconstruction of its main line railways over the maintenance of the Underground network. The unfinished parts of the New Works Programme were gradually shelved or postponed.

However the BTC did authorise the completion of the electrification of the network, seeking to replace steam locomotives on the parts of the system where they still operated. This phase of the programme was completed when the Metropolitan Line was electrified to Chesham in 1960. Steam locomotives were fully withdrawn from London Underground passenger services on 9 September 1961, when British Railways took over the operations of the Metropolitan line between Amersham and Aylesbury. The last steam shunting and freight locomotive was withdrawn from service in 1971.

In 1963 the LTE was replaced by the London Transport Board, directly accountable to the Ministry of Transport. On 1 January 1970, the Greater London Council (GLC) took over responsibility for London Transport.

The first real post-war investment in the network came with the carefully planned Victoria Line, which was built on a diagonal northeast-southwest alignment beneath Central London, incorporating centralised signalling control and automatically driven trains, and opened in stages between 1968 and 1971. The Piccadilly line was extended to Heathrow Airport in 1977, and the Jubilee line was opened in 1979, taking over part of the Bakerloo line, with new tunnels between Baker Street and Charing Cross.

In 1994, with the privatisation of British Rail, LRT took control of the Waterloo and City line, incorporating it into the Underground network for the first time. This year also saw the end of services on the little used Epping-Ongar branch of the Central Line and the Aldwych branch of the Piccadilly Line after it was agreed that necessary maintenance and upgrade work would not be cost effective.

In 1999 the Jubilee line extension to Stratford in London’s East End was completed. This plan included the opening of a completely refurbished interchange station at Westminster. The Jubilee line’s old terminal platforms at Charing Cross were closed but maintained operable for emergencies.

Public Private Partnership [ ]

The route of the District line through the London Boroughs (2013).

Transport for London (TfL) replaced LRT in 2000, a development that coincided with the creation of a directly-elected Mayor of London and the Greater London Assembly.

In January 2003 the Underground began operating as a Public-Private Partnership (PPP), whereby the infrastructure and rolling stock were maintained by two private companies (Metronet and Tube Lines) under 30-year contracts, whilst London Underground Limited remained publicly owned and operated by TfL.

There was much controversy over the implementation of the PPP. Supporters of the change claimed that the private sector would eliminate the inefficiencies of public sector enterprises and take on the risks associated with running the network, while opponents said that the need to make profits would reduce the investment and public service aspects of the Underground. There has since been criticism of the performance of the private companies; for example the January 2007 edition of The Londoner, a newsletter published periodically by the Greater London Authority, listed Metronet’s mistakes of 2006 under the headline Metronet guilty of ‘inexcusable failures’.

Metronet was placed into administration on 18 July 2007.TfL has since taken over Metronet’s outstanding commitments.

The UK government has made concerted efforts to find another private firm to fill the vacuum left by the liquidation of Metronet. However so far only TfL has expressed a plausible interest in taking over Metronet’s responsibilities. Even though Tube Lines appears to be stable, this has put the long-term future of the PPP scheme in doubt. The case for PPP was also weakened in 2008 when it was revealed that the demise of Metronet had cost the UK government £2 billion. The five private companies that made up the Metronet alliance had to pay £70m each towards paying off the debts acquired by the consortium. But under a deal struck with the government in 2003, when the PPP scheme began operating, the companies were protected from any further liability. The UK taxpayer therefore had to foot the rest of the bill. This undermined the argument that the PPP would place the risks involved in running the network into the hands of the private sector.

Northern Line extension [ ]

In 2021, the Northern Line was extended with a branch running from Kennington to two new stations at Nine Elms and Battersea Power Station. This connects to the Charing Cross branch only, so passengers for the Bank branch have to change at Kennington. There are longer term proposals to extend the new line to Clapham Junction, but this most likely won’t happen until Crossrail 2 opens, as trains would likely become so full at Clapham Junction that passengers at the other two stations would be unable to board. Unlike the Jubilee Extension, the new stations don’t have platform edge doors, but they have been designed so they can be retrofitted with them.

Transport for London [ ]

Transport for London (TfL) was created in 2000 as the integrated body responsible for London’s transport system. It replaced London Regional Transport. It assumed control of London Underground Limited in July 2003.

TfL is part of the Greater London Authority and is constituted as a statutory corporation regulated under local government finance rules.[20] It has three subsidiaries: London Transport Insurance (Guernsey) Ltd., the TfL Pension Fund Trustee Co. Ltd. and Transport Trading Ltd (TTL). TTL has six wholly-owned subsidiaries, one of which is London Underground Limited.

The TfL Board is appointed by the Mayor of London. The Mayor also sets the structure and level of public transport fares in London. However the day-to-day running of the corporation is left to the Commissioner of Transport for London. The current Commissioner is Peter Hendy.

The Mayor is responsible for producing an integrated transport strategy for London and for consulting the GLA, TfL, local councils and others on the strategy. The Mayor is also responsible for setting TfL’s budget. The GLA is consulted on the Mayor’s transport strategy, and inspects and approves the Mayor’s budget. It is able to summon the Mayor and senior staff to account for TfL’s performance. London TravelWatch, a body appointed by and reporting to the Assembly, deals with complaints about transport in London.

Infrastructure [ ]

London Underground Battery locos 25 54 on Engineers Train 674 @ Rayners Lane 30 12 13

London Underground Battery locos 25+54 on Engineers Train 674 @ Rayners Lane 30/12/13.

See the Wikipedia page [1].

Stations and lines [ ]

Route map of London Underground, London Overground, Docklands Light Railway and Crossrail, including most green-lighted proposals. Author- User: Sameboat.

The London Underground’s 11 lines are the Bakerloo Line, Central Line, Circle line, District Line, Hammersmith & City Line, Jubilee Line, Metropolitan Line, Northern Line, Piccadilly Line, Victoria Line, and Waterloo & City Line. Until 2007 there was a twelfth line, the East London Line, but this closed for conversion work and was transferred to the London Overground when it reopened in 2010.

Prior to its transfer to the London Underground in 1994, the Waterloo and City line was operated by British Rail and its mainline predecessors. The line fist began appearing on most tube maps, from the mid-1930s.

| Name | Map colour | First operated | First section opened * | Name dates from | Type | Length /km | Length /miles | Stations | Journeys per annum (000s) | Average journeys per mile (000s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bakerloo Line | Brown | 1906 | 1906 | 1906 | Deep level | 23.2 | 14.5 | 25 | 95,947 | 6,617 |

| Central Line | Red | 1900 | 1856 | 1900 | Deep level | 74 | 46 | 49 | 183,582 | 3,990 |

| Circle Line | Yellow | 1884 | 1863 | 1949 | Subsurface | 22.5 | 14 | 27 | 68,485 | 4,892 |

| District Line | Green | 1868 | 1858 | 1868-1905 | Subsurface | 64 | 40 | 60 | 172,879 | 4,322 |

| Hammersmith & City Line | Pink | 1863 | 1858 | 1988 | Subsurface | 26.5 | 16.5 | 28 | 45,845 | 2,778 |

| Jubilee Line | Grey | 1979 | 1879 | 1979 | Deep level | 36.2 | 22.5 | 27 | 127,584 | 5,670 |

| Metropolitan Line | Corporate Magenta | 1863 | 1863 | 1863 | Subsurface | 66.7 | 41.5 | 34 | 53,697 | 1,294 |

| Northern Line | Black | 1890 | 1867 | 1937 | Deep level | 58 | 36 | 50 | 206,987 | 5,743 |

| Piccadilly Line | Dark Blue | 1906 | 1869 | 1906 | Deep level | 71 | 44.3 | 52 | 176,177 | 3,977 |

| Victoria Line | Light Blue | 1968 | 1968 | 1968 | Deep level | 21 | 13.25 | 16 | 161,319 | 12,175 |

| Waterloo & City Line | Teal | 1898 | 1898 | 1898 | Deep level | 2.5 | 1.5 | 2 | 9,616 | 6,410 |

| Tramlink | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | Deep level | 1.3 | 2.1 | 6 | 10,166 | 2,322 | |

| * Where a year is shown that is earlier than that shown for First operated, this indicates that the line operates over a route first operated by another Underground line or by another railway company. | ||||||||||

Lines on the Underground can be classified into two types: subsurface and deep-level. The subsurface lines were dug by the cut-and-cover method, with the tracks running about 5 m (16 ft 5 in) below the surface. The deep-level or tube lines, bored using a tunnelling shield, run about 20 m (65 ft 7 in) below the surface (although this varies considerably), with each track in a separate tunnel. These tunnels can have a diameter as small as 3.56 m (11 ft 8 in) and the loading gauge is thus considerably smaller than on the subsurface lines. Lines of both types usually emerge onto the surface outside the central area.

While the tube lines are for the most part self-contained, the subsurface lines are part of an interconnected network: each shares track with at least two other lines. The subsurface arrangement is similar to the New York City Subway, which also runs separate «lines» over shared tracks.

Rolling stock and electrification [ ]

P stock in red with R Stock at Upminster. CP (red) and R (white) stock District Line trains at Upminster Station. Photographed by SPSmiler.

The Underground uses rolling stock built between 1960 and 2005. Stock on subsurface lines is identified by a letter (such as A Stock, used on the Metropolitan line), while tube stock is identified by the year in which it was designed (for example, 1996 Stock, used on the Jubilee line). All lines are worked by a single type of stock except the District line, which uses both C and D Stock. Two types of stock are currently being developed — 2009 Stock for the Victoria line and S stock for the subsurface lines, with the Metropolitan line A Stock being replaced first. Rollout of both is expected to begin about 2009. In addition to the Electric Multiple Units described above, there is engineering stock, such as ballast trains and brake vans, identified by a 1-3 letter prefix then a number.

The Deep Tube Programme, is investigating into replacing the trains for the Bakerloo and Piccadilly lines. It is also looking for trains with better energy conservation and regenerative braking.

Of all the stations on the network, 135 of them are below street/ground level, this equates to 50% of the 270 stations.

The number of below ground stations will rise from 135 to 138 once new stations are built at Nine Elms, Battersea Park and Watford High Street (which is already on the London Overground).

The number of overground stations will rise from 135 to 137 with the opening of the Cassiobridge, Watford JCN and Watford Vicarage Road stations along with the closure of the little used current Watford tube station.

By line these are the sections below ground that contain stations, small tunnels/cuttings that contain no stations are not included.

Bakerloo Line: Between Queens Park and the terminus at Elephant and Castle.

Central Line: Between East Acton and Stratford and another section containing the Wanstead, Redbridge and Gants Hill stations. North Acton station is in a cutting.

Circle Line: All of the line apart from the Hammersmith Branch beyond Paddington.

District Line: Between Ravenscourt Park and Bromley By Bow, with Fulham Broadway in it’s own tunnelled section.

Hammersmith and City Line: Between Royal Oak and Bromley By Bow.

Jubilee Line: Between West Hampstead and Canning Town.

Metropolitan Line: Between Wembley Park and the Terminus at Aldgate, Harrow on the Hill is in a cutting.

Northern Line: Morden (which is in a cutting) to East Finchley/Golders Green.

Piccadilly Line: Between Turnham Green and Arnos Grove with another tunnelled section between Hounslow West and the Terminus at Heathrow Terminal 5. Southgate station is in it’s own short tunnelled section.

Victoria Line: Entirely Underground.

Waterloo and City Line: Entirely Underground

Cooling [ ]

In summer, temperatures on parts of the London Underground can become very uncomfortable due to its deep and poorly ventilated tube tunnels: temperatures as high as 47 °C (117 °F) were reported in the 2006 European heat wave. Posters may be observed on the Underground network advising that passengers carry a bottle of water to help keep cool.

Planned improvements and expansions [ ]

There are many planned improvements to the London Underground. A new station opened on the Piccadilly line at Heathrow Airport Terminal 5 on 27 March 2008 and is the first extension of the London Underground since 1999. Each line is being upgraded to improve capacity and reliability, with new computerised signalling, automatic train operation (ATO), track replacement and station refurbishment, and, where needed, new rolling stock. A trial programme for a groundwater cooling system in Victoria station took place in 2006 and 2007; it aimed to determine whether such a system would be feasible and effective if in widespread use. A trial of mobile phone coverage on the Waterloo & City line aims to determine whether coverage can be extended across the rest of the Underground network. Although not part of London Underground, the Crossrail scheme will provide a new route across central London integrated with the tube network.

The long proposed Chelsea-Hackney line, which is planned to begin operation in 2025, may be part of the London Underground, which would mean it would give the network a new Northeast to South cross London line to provide more interchanges with other lines and relieve overcrowding on other lines. However it is still on the drawing board. It was first proposed in 1901 and has been in planning since then. In 2007 the line was passed over to Cross London Rail Ltd, the current developers of Crossrail. Therefore, the line may be either part of the London Underground network or the National Rail network. There are advantages and disadvantages for both.

The Croxley Rail Link proposal envisages diverting the Metropolitan line Watford branch to Watford Junction station along a disused railway track. The project awaits funding from Hertfordshire County Council and the Department for Transport, and remains at the proposal stage.

Travelling [ ]

Ticketing [ ]

The Underground uses TfL’s Travelcard zones to calculate fares. Greater London is divided into 6 zones; Zone 1 is the most central, with a boundary just beyond the Circle line, and Zone 6 is the outermost and includes London Heathrow Airport. Stations on the Metropolitan line outside Greater London are in Zones 7-9.

Travelcard zones 7-9 also apply on the Euston-Watford Junction line (part of the London Overground) as far as Watford High Street. Watford Junction is outside these zones and special fares apply.

There are staffed ticket offices, some open for limited periods only, and ticket machines usable at any time. Some machines that sell a limited range of tickets accept coins only, other touch-screen machines accept coins and banknotes, and usually give change. These machines also accept major credit and debit cards: some newer machines accept cards only.

More recently, TfL has introduced the Oyster card, a smartcard with an embedded contactless RFID chip, that travellers can obtain, charge with credit, and use to pay for travel. Like Travelcards they can be used on the Underground, buses, trams and the Docklands Light Railway. The Oyster card is cheaper to operate than cash ticketing or the older-style magnetic-strip-based Travelcards, and the Underground is encouraging passengers to use Oyster cards instead of Travelcards and cash (on buses) by implementing significant price differences. Oyster-based Travelcards can be used on National Rail throughout London. Pay as you go is available on a restricted, but increasing, number of routes.

For tourists or other non-residents, not needing to travel in the morning peak period, the all day travelcard is the best ticketing option available. These are available from any underground station. These cost around £5.50 and allow unlimited travel on the network from 9:30am onward for the rest of the day. This provides excellent value for money and a huge saving considering one single journey on the network can cost close to £5. Travel cards for multiple days are also available.

Penalty fares and fare evasion [ ]

In addition to automatic and staffed ticket gates, the Underground is patrolled by both uniformed and plain-clothes ticket inspectors with hand-held Oyster card readers. Passengers travelling without a ticket valid for their entire journey are required to pay at least a £20 penalty fare and can be prosecuted for fare evasion under the Regulation of Railways Act 1889 under which they are subject to a fine of up to £1,000, or three months’ imprisonment. Oyster pre-pay users who have failed to touch in at the start of their journey are charged the maximum cash fare (£4, or £5 at some National Rail stations) upon touching out. In addition, an Oyster card user who has failed to touch in at the start of their journey and who is detected mid-journey (i.e. on a train) by an Inspector is now liable to a penalty fare of £20. No £4 maximum charge will be applied at their destination as the inspector will apply an ‘exit token’ to their card.

While the Conditions of Carriage require period Travelcard holders to touch in and touch out at the start and end of their journey, any Oystercard user who has a valid period Travelcard covering their entire journey is not liable to pay a Penalty fare where they have not touched in. Neither the Conditions of Carriage or Schedule 17 of the Greater London Authority Act 1999, which shows how and when Penalty fares can be issued, would allow the issuing of a Penalty fare to a traveler who had already paid the correct fare for their journey.

Delays [ ]

According to statistics obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, the average commuter on the Metropolitan line wasted three days, 10 hours and 25 minutes in 2006 due to delays (not including missed connections). Between 17 September 2006 and 14 October 2006, figures show that 211 train services were delayed by more than 15 minutes. Passengers are entitled to a refund if their journey is delayed by 15 minutes or more due to circumstances within the control of TfL.

Hours of operation [ ]

Accessibility [ ]

Accessibility by people with mobility issues was not considered when most of the system was built, and most older stations are inaccessible to disabled people. More recent stations were designed for accessibility, but retrofitting accessibility features to old stations is at best prohibitively expensive and technically extremely difficult, and often impossible. Even when there are already escalators or lifts, there are often steps between the lift or escalator landings and the platforms.

Most stations on the surface have at least a short flight of stairs to gain access from street level, and the great majority of below-ground stations require use of stairs or some of the system’s 410 escalators (each going at a speed of 145 ft (44 m) per minute, approximately 1.65 mph (3 km/h)). There are also some lengthy walks and further flights of steps required to gain access to platforms. The emergency stairs at Covent Garden station have 193 steps (the equivalent climbing a 15-storey building) to reach the exit, so passengers are advised to use the lifts as climbing the steps can be dangerous.

The escalators in Underground stations include some of the longest in Europe, and all are custom-built. The longest escalator is at Angel station, 60 m (197 ft) long, with a vertical rise of 27.5 m (90 ft). They run 20 hours a day, 364 days a year, with 95% of them operational at any one time, and can cope with 13,000 passengers per hour. Convention and signage stipulate that people using escalators on the Underground stand on the right-hand side so as not to obstruct those who walk past them on the left.

TfL produces a map indicating which stations are accessible, and since 2004 line maps indicate with a wheelchair symbol those stations that provide step-free access from street level. Step height from platform to train is up to 300 mm (11.8 in), and there can be a large gap between the train and curved platforms. Only the Jubilee Line Extension is completely accessible.

TfL plans that by 2020 there should be a network of over 100 fully accessible stations, consists of those recently built or rebuilt, and a handful of suburban stations that happen to have level access, along with selected ‘key stations’, which will be rebuilt. These key stations have been chosen due to high usage, interchange potential, and geographic spread, so that up to 75% of journeys will be achievable step-free.

Overcrowding [ ]

Overcrowding on the Underground has been of concern for years and is very much the norm for most commuters especially during the morning and evening rush hours. Stations which particularly have a problem include Camden Town station and Covent Garden, which have access restrictions at certain times. Restrictions are introduced at other stations when necessary. Several stations have been rebuilt to deal with overcrowding issues, with Clapham Common and Clapham North on the Northern line being the last remaining stations with a single narrow platform with tracks on both sides. At particularly busy occasions, such as football matches, British Transport Police may be present to help with overcrowding. On 24 September 2007 King’s Cross underground station was totally closed due to «overcrowding». According to a 2003 House of Commons report, commuters face a «daily trauma» and are forced to travel in «intolerable conditions».

Safety [ ]

39-tonne train out of control dangerously through central London-0

A 39-tonne maintenance train out of control dangerously through central London.

Seconds From Disaster King’s Cross Fire

Seconds From Disaster King’s Cross Fire.

Wooden escalators at Greenford tube station in 2006, similar to those that caught fire at King’s Cross. The escalator was eventually decommissioned on 10 March 2014 to give the station step-free access.

Accidents on the Underground network, which carries around a billion passengers a year, are rare. There is one fatal accident for every 300 million journeys. There are several safety warnings given to passengers, such as the ‘mind the gap’ announcement and the regular announcements for passengers to keep behind the yellow line. Relatively few accidents are caused by overcrowding on the platforms, and staff monitor platforms and passageways at busy times prevent people entering the system if they become overcrowded.

Most fatalities on the network are suicides. Most platforms at deep tube stations have pits beneath the track, originally constructed to aid drainage of water from the platforms, but they also help prevent death or serious injury when a passenger falls or jumps in front of a train.

The King’s Cross fire broke out on November 18th, 1987, at approximately 19:30 at King’s Cross St. On an escalator serving the Piccadilly line at King’s Cross/Pancras tube station, a major interchange on the London Underground.

The subsequent public inquiry determined that the fire had started due to a lit match being dropped onto the escalator a 48 year old wooden escalator serving the Piccadilly line and 15 minutes after being reported, as the first members of the London Fire Brigade were investigating, the fire flashed over, filling the underground ticket office with heat and smoke. It had suddenly increased in intensity over those 15 minuets due to a previously unknown trench effect.

All wooden escalators were replaced in the years following the King’s Cross fire in 1987 and smoking was banned by 2006.

Sadly, the fire killed 31 people and injured 100 people.

Image [ ]

TfL’s Tube map and «roundel» logo are instantly recognisable by any Londoner, almost any Briton, and many people around the world. The original maps were often street maps with the lines superimposed, and the stylised Tube map evolved from a design by electrical engineer Harry Beck in 1931. Virtually every major urban rail system in the world now has a map in a similar stylised layout and many bus companies have also adopted the concept. TfL licences the sale of clothing and other accessories featuring its graphic elements and it takes legal action against unauthorised use of its trademarks and of the Tube map. Nevertheless, unauthorised copies of the logo continue to crop up worldwide. The announcement «mind the gap», heard when trains stop at certain platforms, has also become a well known catchphrase.

The roundel [ ]

The origins of the roundel, in earlier years known as the ‘bulls-eye’ or ‘target’, are obscure. While the first use of a roundel in a London transport context was the 19th-century symbol of the London General Omnibus Company — a wheel with a bar across the centre bearing the word GENERAL — its usage on the Underground stems from the decision in 1908 to find a more obvious way of highlighting station names on platforms. The red circle with blue name bar was quickly adopted, with the word «UNDERGROUND» across the bar, as an early corporate identity. The logo was modified by Edward Johnston in 1919.

Each station displays the Underground roundel, often containing the station’s name in the central bar, at entrances and repeatedly along the platform, so that the name can easily be seen by passengers on arriving trains.

The roundel has been used for buses and the tube for many years, and since TfL took control it has been applied to other transport types (taxi, tram, DLR, etc.) in different colour pairs. The roundel has to some extent become a symbol for London itself.

Typography [ ]

Edward Johnston designed TfL’s distinctive sans-serif typeface, in 1916. «New Johnston», modified to include lower case, is still in use. It is noted for the curl at the bottom of the minuscule l, which other sans-serif typefaces have discarded, and for the diamond-shaped tittle on the minuscule i and j, whose shape also appears in the full stop, and is the origin of other punctuation marks in the face. TfL owns the copyright to and exercises control over the New Johnston typeface, but a close approximation of the face exists in the TrueType computer font Paddington, and the Gill Sans typeface also takes inspiration from Johnston.

Contribution to arts [ ]

Its artistic legacy includes the employment since the 1920s of many well-known graphic designers, illustrators and artists for its own publicity posters. Designers who produced work for the Underground in the 1920s and 1930s include Man Ray, Edward McKnight Kauffer and Fougasse. In recent years the Underground has commissioned work from leading artists including R. B. Kitaj, John Bellany and Howard Hodgkin.

In architecture, Leslie Green established a house style for the new stations built in the first decade of the 20th century for the Bakerloo, Piccadilly and Northern lines which included individual Edwardian tile patterns on platform walls. In the 1920s and 1930s, Charles Holden designed a series of modernist and art-deco stations for which the Underground remains famous. Holden’s design for the Underground’s headquarters building at 55 Broadway included avant-garde sculptures by Jacob Epstein, Eric Gill and Henry Moore (his first public commission). Misha Black was appointed design consultant for the 1960s Victoria Line, contributing to the line’s uniform look, while the 1990s extension of the Jubilee line featured stations designed by leading architects such as Norman Foster, Michael Hopkins and Will Alsop.

Many stations also feature unique interior designs to help passenger identification. Often these have themes of local significance. Tiling at Baker Street incorporates repetitions of Sherlock Holmes’s silhouette. Tottenham Court Road features semi-abstract mosaics by Eduardo Paolozzi representing the local music industry at Denmark Street. Northern line platforms at Charing Cross feature murals by David Gentleman of the construction of Charing Cross itself.

In popular culture [ ]

The Underground has been featured in many movies and television shows, including Sliding Doors, Tube Tales and Neverwhere. The London Underground Film Office handles over 100 requests per month. The Underground has also featured in music such as The Jam’s «Down in the Tube Station at Midnight» and in literature such as the graphic novel V for Vendetta. Popular legends about the Underground being haunted persist to this day.

After placing a number of spoof announcements on her web page, the London Underground’s voiceover artiste Emma Clarke had further contracts cancelled in 2007.

Videos [ ]

London Underground 2012

London Underground 2012, a video-mix of London Underground trains around the whole network.

London Underground 2012 HD

London Underground 2012[HD]. You can see the different rolling stocks and stations and short rides for example A60 Stock.

London Underground History

The beginning of the first urban train: the tube.

To explain the origin of the London Underground we have to travel back in time to place ourselves in the Industrial Revolution. When the rural population began their exodus to the cities in search of better working conditions, they began to experience super population phenomena. London became one of the most populated cities in the world. This led to real problems of logistics, communication and congestion in London and between London and its suburbs. In mid-nineteenth century using the occassion of some city works the idea of underground access to the city center was taken into account.

Charles Pearson, a councilor at the time, already had a rather futuristic vision subtarráneos network trains. His network design consisted of a sort of atmospheric cabs driven by compressed air.

The history of London Underground begins with the celebration of the Great Exhibition in 1851 when the project with the construction of the first line, known as the North Metropolitan Railway materializes. The advancement of technology, specifically the passage of steam locomotives to electric trains, was the final push to meet The Tube, as we know it today. In 1905 the vast majority of the tracks were electrified. This technological advancement, along with new techniques for building tunnels, are facts that mark the history of the London Underground.

Today the London Underground is the largest network of subways in the world. The total length of its lines is 408 kilometers, 181 of which are underground. There is also a light rail, the Docklands Light Railway, which adds 26 kms to this network. The London Underground has 275 stations and it’s used by more than 3 million users every day.

London Underground: A very changing history.

The London Underground, also known as underground or tube is the oldest underground network and also the most used in the planet. Its history has been characterized by rapidly changing. Along its route we find abandoned, renamed, relocated stations and even stations merged with other stations.

Examples of this can be found in the path of Tottenham Court Road Holborn in Central line,. We find a station without passengers since 1932 (it used to be the British Museum station).

Also in the Piccadilly Line between Green Park and Hyde Park Corner changes are observed in the construction of the wall of the tunnel. This used to be a station, Down Street, closed the same year than the British Museum. These stations are known as ghost stations.

Many stations have changed the name they were originally baptized. Normally the area where the metro station was located was renamed. In other cases the name was changed to join two stations. And even for competitive reasons as there are lines managed by different companies, usually competitors, which are close and their interest is clearly distinguished lines.

There are about 40 stations abandoned or relocated in the London underground network along its 408 km of tracks. Some have disappeared without a trace, while others are almost intact, leaving as snapshots of the time when they were closed.

Construction of the London Underground

The development of the network of underground railways in the City has been linked to the advancement of technology. Cut and cover tunnels and deep underground tunnels: Two types of techniques have two types of tunnels underground network led.

What are cut and cover tunnels?

Cut and cover is the most obvious technology in the construction of underground tunnels, and first level deep were built with this technic. It is simply dig the route and then cover the tunnel with steel beams or some other sturdy material.

It was first used in the construction of the London Underground journey between Paddington and King’s Cross, led by Charles Pearson.

Tunnels deep underground.

In the nineteenth century there wasn’t an efficient technology to build tunnels as trains were mainly steam based. The depth at which they could dig the tunnels was limited by having to devise channels to ventilate and evacuate fumes and gases from the steam. Furthermore trains size needed that the diameter of the tunnels was much higher.

The first tunnel built under the River Thames was Brunell tunnel used by east line and it was a very expensive work. When traction machines could be replaced by electricity, this scenario changed. The construction of the tunnels was simplified to be able to make smaller tunnels (being smaller trains) and then ignore all the smoke evacuation system and residues. Moreover James Henry Greathead devised a method for tunneling using compressed air which allowed dig very quickly and deeper.

Defining tube line.

The London Underground is often incorrectly called Tube. Should refer only to certain parts of the London Underground with this name.

A metro line to be considered a line of tube must have certain characteristics: they must move underground on circular tunnels, each path must travel through a separate tunnel except at intersections and other stations. These tunnels are usually deeper relative to the level of the normal lines.

This differentiation can see in the first maps of the network. The 1929 map below distinguish between tube lines (the lines moving at a deeper level), and other major lines.

Esta entrada también está disponible en: Spanish French

English Online

The London Underground

The London Underground, or the Tube as it is often called, is the oldest underground train network in the world. Opened in 1863 there are a total of eleven lines, 270 stations and over 400 km of track, making it the third longest subway system in the world. The London Underground carries over a billion passengers a year, or about 3 million every day. The deepest stations are over 60 metres below the surface, however 55% of the tracks run above it.

In the 1830s London’s authorities had the idea of linking the centre of London with the large train stations which were located farther away. In 1863 the first underground railway, the Metropolitan Line, opened. Wooden carriages were powered by steam locomotives. The system of tracks gradually expanded. By the end of the 19th century most lines used electricity to power the trains. During World War II many tube stations were air-raid shelters where people sought protection during the German bombing of the city.

Over the course of history, the size of the tunnels changed, so that today, two different types of trains travel across the city. Modern escalators bring passengers to the deep level stations of the tube. The Jubilee Line is the last line to be built. It was opened in 1979 in honour of Queen Elizabeth’s 25th anniversary as monarch. In the 1990s it was extended eastwards to the Docklands.

The London Underground normally operates daily between 5 a.m. and midnight. Some lines stay open throughout the night on special occasions, like New Year’s Eve. London Underground stations can get very crowded during the weekday rush hours. Even though the system is so large, trains usually run on time. Over the decades underground stations have been modernized. In the past years many have been equipped with Wi-Fi access to make journeys as comfortable as possible. The well-known symbol of the London Underground, a red circle with a blue bar, was developed at the beginning of the 20th century and has not changed much since then.

Some of London’s Underground stations are buildings which have a special architectural value. Many original stations have been restored and look similar to the way they did over a century ago.

Although so many people use the underground every day, the safety record of the system is very good. Most deaths occur as suicides.

The London Underground also faces environmental problems.В Because the water level of the Thames is constantly on the rise, thousands of cubic metres of water must be pumped out of some of the underground stations every day.

London Underground: the Tube

The London Underground network is divided into nine zones. Central London is covered by zone 1.

The Tube network has 11 lines.

The Tube fare depends on how far you travel, the time of day, and whether you use a single fare paper ticket or a payment card.

Oyster cards or contactless payments are the cheapest ways to pay for Tube journeys.

Tube services usually run from 5am until midnight, with Night Tube services on some lines on Friday and Saturday evenings.

Content contains affiliate links – marked with asterisks. If you click through and make a purchase, Visit London receives a commission which is put back into our work promoting London.

Greater London is served by 11 Tube lines, along with the Docklands Light Railway (DLR), the London Overground, the Elizabeth line and National Rail services.

London Underground trains generally run between 5am and midnight Monday to Saturday. Operating hours are slightly reduced on Sunday. Night Tube trains run on some lines throughout the night on Fridays and Saturdays.

For more detailed travel information on which stations to use and suggestions for the best route to reach your destination, use Transport for London’s Journey Planner.

What are the London Underground zones?

London’s public transport network is divided into nine travel zones. Zone 1 is in central London and zones 6 to 9 are on the outskirts of the city.

The Elizabeth line

Hop onboard London’s Elizabeth line, which connects Heathrow airport and Reading to Shenfield and Abbey Wood via major central London Underground and Rail stations including Paddington, Liverpool Street and Canary Wharf stations.

From October 2022, the Elizabeth line from Heathrow airport will connect with the central tunnels of the line, making the journey from Heathrow to central London in 15 minutes.

What are the London Tube prices?

Buy a Visitor Oyster card*, Oyster card, Travelcard or use a contactless payment card to get the best value. Paying cash for a single paper ticket is the most expensive way to travel. Check out this guide to cheap travel for more money-saving tips when travelling in London.

An adult cash fare on the London Underground for a single journey in zone 1 is £6.30. The same Tube fare with a Visitor Oyster card, Oyster card or contactless payment card is £2.50. For more details about London Tube prices, see the Transport for London website.

If your contactless payment card was issued outside the UK, check with your bank before you travel to see whether you’ll incur additional transaction fees or charges.

Find out more information about London Oyster cards with these frequently asked questions.

If you plan on travelling around London to do some sightseeing and visit some of London’s best attractions, a London Pass* could save you money.

Buy a Visitor Oyster Card*

Is there a London Tube map?

Devised in 1933 by Harry Beck, the London Underground map is a 20th-century design classic. It’s useful and clearly indicates the general directions taken by the trains (north, south, east or westbound), with all interchanges clearly shown.

Download free London travel maps of the London Underground and other public transport routes.

Are free London Tube maps and guides available?

Transport for London (TfL) produces free maps and guides to help you get around. You can pick up a London Underground map upon arrival at any London Tube station. London Travel information centres sell tickets and provide free maps, and you’ll find centres at Victoria, Piccadilly Circus and King’s Cross & St Pancras stations, as well as at Tourist Information Centres.

Download a handy free Tube map, as well as maps for other modes of public transport.

What are useful tips for Tube travellers?

Here are some useful tips for travelling on the Tube to make your journey more enjoyable and efficient.

What are the London Underground opening and closing times?

London Underground opening times vary slightly from line to line, but the first Tube trains normally start running around 5am from Monday to Saturday, with reduced operating hours on Sunday.

The London Underground normally runs until around midnight. Check signage or with staff at the particular Tube station you plan on using to find out exactly when the last train is.

A 24-hour Night Tube service operates on some lines on Fridays and Saturdays.

How accessible is the London Underground?

Access to most Tube stations is via staircases or escalators, but some London Underground stations have step-free access. When boarding London Underground trains, be aware that you might have to step up to eight inches (20cm) up or down between the platform and the train.

All 41 stations along the Elizabeth line are set to be accessible with step-free access from platform to street level.

Download a free London Tube map to see which stations are step-free or find guides on accessible travel from Transport for London.