What is the mammal in the world

What is the mammal in the world

What Is The Largest Land Mammal In The World?

The Largest Animal Ever: The Blue Whale

The blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) is a marine mammal belonging to the suborder of baleen whales.

At 30 metres (98 ft) in length and 180 metric tons (200 short tons) or more in weight, it is the largest known animal to have ever existed.

What is the largest land mammal?

African bush elephant

What is the largest mammal to ever walk the earth?

For over a century, Paraceratherium – a 26-foot-long, 15 ton, hornless rhino – has been cited as the biggest of the big beasts. But, according to a new paper by Asier Larramendi, ancient elephants are in close competition for the title of the largest mammals to ever walk the Earth.

What was the largest carnivorous mammal?

Arctodus doubled a grizzly bear in size: it was 183 cm (6 ft) tall at the shoulder on all four legs, and raised up 3.35 m (11 ft) tall. It weighed up to 900 kg (2,000 pounds). But the largest carnivorous mammal that ever existed was not related to modern Carnivora, but to the hoofed mammals.

What’s the largest creature in the world?

Top 10 Biggest Animals

What is the biggest creature that ever lived?

What is bigger than a blue whale?

Blue whales are the largest animals ever known to exist. Bigger than dinosaurs, bigger than mastodons, a blue whale can reach up to almost 100 feet long and have been weighed at as much as 191 tons.

Is a megalodon bigger than a blue whale?

Monster-size sharks in The Meg reach lengths of 20 to 25 meters (66 to 82 feet). That’s massive, although a tad smaller than the longest known blue whales. Scientists have made estimates of how big C. megalodon got, based on the size of their fossil teeth. Even the largest reached only 18 meters (about 60 feet).

Is a blue whale bigger than dinosaurs?

Now paleontologists have announced a species proposed to be most massive dinosaur ever discovered: an enormous herbivore estimated at over 120 feet long and weighing over 70 tons—or longer than a blue whale and heavier than a dozen African elephants.

Quick Answer: What Is The Largest Mammal In The World?

What is the largest mammal to ever walk the earth?

For over a century, Paraceratherium – a 26-foot-long, 15 ton, hornless rhino – has been cited as the biggest of the big beasts.

But, according to a new paper by Asier Larramendi, ancient elephants are in close competition for the title of the largest mammals to ever walk the Earth.

What is the biggest land mammal in the world?

African bush elephant

What is tallest mammal?

Giraffes are the world’s tallest mammals, thanks to their towering legs and long necks. A giraffe’s legs alone are taller than many humans—about 6 feet (1.8 meters).

What is the second biggest mammal?

Whales (Cetacea) The largest whale (and largest mammal, as well as the largest animal known ever to have existed) is the blue whale, a baleen whale (Mysticeti).

Is a megalodon bigger than a blue whale?

Monster-size sharks in The Meg reach lengths of 20 to 25 meters (66 to 82 feet). That’s massive, although a tad smaller than the longest known blue whales. Scientists have made estimates of how big C. megalodon got, based on the size of their fossil teeth. Even the largest reached only 18 meters (about 60 feet).

What is bigger than a blue whale?

Blue whales are the largest animals ever known to exist. Bigger than dinosaurs, bigger than mastodons, a blue whale can reach up to almost 100 feet long and have been weighed at as much as 191 tons.

What is the deadliest animal in the world?

Here, the ten most dangerous animals in the world.

Is a blue whale bigger than dinosaurs?

Now paleontologists have announced a species proposed to be most massive dinosaur ever discovered: an enormous herbivore estimated at over 120 feet long and weighing over 70 tons—or longer than a blue whale and heavier than a dozen African elephants.

What is the largest order of mammals?

Most mammals, including the six most species-rich orders, belong to the placental group. The three largest orders in numbers of species are Rodentia: mice, rats, porcupines, beavers, capybaras and other gnawing mammals; Chiroptera: bats; and Soricomorpha: shrews, moles and solenodons.

How tall is a blue whale?

What is the fattest animal in the world?

There are plenty of supersized animals out there. But determining which animal is the fattest isn’t as straightforward as it may appear. As the largest animal in the world, the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) also has the most fat.

How long do giraffes sleep a day?

What are the largest whales?

North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) are big, but they’re not the biggest whales. That distinction goes to the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus), the largest animal on Earth. The orca’s (Orcinus orca) size of up to 31 feet (9.4 meters) makes it the largest dolphin.

What is the largest rodent?

What is the world’s largest carnivore?

The largest terrestrial carnivore is the polar bear (Ursus maritimus). Adult males typically weigh 400–600 kg (880–1,320 lb), and have a nose-to-tail length of 2.4–2.6 m (7 ft 10 in–8 ft 6 in).

Could Megalodon still live in the deep ocean?

‘No. It’s definitely not alive in the deep oceans, despite what the Discovery Channel has said in the past,’ notes Emma. ‘If an animal as big as megalodon still lived in the oceans we would know about it.’

What is bigger than a Megalodon?

Megalodon could grow up to 60 feet (18 meters) long and had a bite more powerful than that of a Tyrannosaurus rex. The sea monsters terrorized the oceans from about 16 million to 2 million years ago. A great white shark compared with the much larger megalodon, and a hapless hypothetical human.

Did Megalodon exist?

Megalodon (Carcharocles megalodon), meaning “big tooth”, is an extinct species of shark that lived approximately 23 to 3.6 million years ago (mya), during the Early Miocene to the end of the Pliocene.

How many blue whales are left?

A 2002 report estimated there were 5,000 to 12,000 blue whales worldwide, in at least five populations. The IUCN estimates that there are probably between 10,000 and 25,000 blue whales worldwide today.

Why is it called a sperm whale?

Etymology. The name sperm whale is a truncation of spermaceti whale. Spermaceti, originally mistakenly identified as the whales’ semen, is the semi-liquid, waxy substance found within the whale’s head (see below).

How big is a giant squid?

Giant squid can grow to a tremendous size due to deep-sea gigantism: recent estimates put the maximum size at 13 m (43 ft) for females and 10 m (33 ft) for males from the posterior fins to the tip of the two long tentacles (second only to the colossal squid at an estimated 14 m (46 ft), one of the largest living

What order of mammals do humans belong to?

Is a lion a mammal?

The lion (Panthera leo) is a large mammal of the Felidae (cat) family. Some large males weigh over 250 kg (550 lb). Today, wild lions live in sub-Saharan Africa and in Asia. The lion is now a vulnerable species.

Is a platypus a mammal?

The platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus), sometimes referred to as the duck-billed platypus, is a semiaquatic egg-laying mammal endemic to eastern Australia, including Tasmania.

Has anyone been swallowed by a whale and survived?

James Bartley (1870–1909) is the central figure in a late nineteenth-century story according to which he was swallowed whole by a sperm whale. He was found still living days later in the stomach of the whale, which was dead from constipation.

Who eats whale meat?

The skin and blubber, known as muktuk, taken from the bowhead, beluga, or narwhal is also valued, and is eaten raw or cooked. Mikigaq is the fermented whale meat.

Mammals

Summary

Wild mammal biomass has declined by 85% since the rise of humans, but there is a possible future where they flourish

Travel back 100,000 years and the planet was rich with a wide array of wild mammals. Mammoths roamed across North America; lions across Europe; 200-kilogram wombats in Australasia; and the ground sloth lounged around South America.

They’re now gone. Since the rise of humans, several hundred of the world’s largest mammals have gone extinct.

While we often think of ecological damage as a modern problem our impacts date back millennia to the times in which humans lived as hunter-gatherers. Our history with wild animals has been a zero-sum game: either we hunted them to extinction, or we destroyed their habitats with agricultural land. Without these natural habitats to expand into and produce food on, the rise of humans would have been impossible. Humans could only thrive at the expense of wild mammals.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. This century marks a pivotal moment: for the first time in human history there is the opportunity for us to thrive alongside, rather than compete with, the other mammals that we share this planet with.

In this article I want to take a look at how the world’s mammals have changed in the past, and how we can pave a better way forward.

As we’ll see, our long history with the other mammals is really a story about meat. Humans have always, and continue to have, a strong drive to eat meat. For our hunter-gatherer ancestors life was about plotting a hunt against the giant 200-kilogram wombat. This later became a story of how to produce the equivalent of a giant wombat in the field. Now we’re focused on how we can produce this in the lab.

The decline of wild mammals has a long history

To understand how the richness of the mammal kingdom has changed we need a metric that captures a range of different animals and is comparable over time. We could look at their abundance – the number of individuals we have – but this is not ideal. We would be counting every species equally, from a mouse to an elephant and this metric would therefore an ecosystem taken over by the smallest mammals look much richer than one in which bigger mammals roam: if the world’s mouse populations multiplied and multiplied – maybe even to the detriment of other animals – then this abundance metric might suggest that these ecosystems were thriving.

Instead, ecologists often use the metric biomass. This means that each animal is measured in tonnes of carbon, the fundamental building block of life. 1 Biomass gives us a measure of the total biological productivity of an ecosystem. It also gives more weight to larger animals at higher levels of the ecological ‘pyramid’: these rely on well-functioning bases below them.

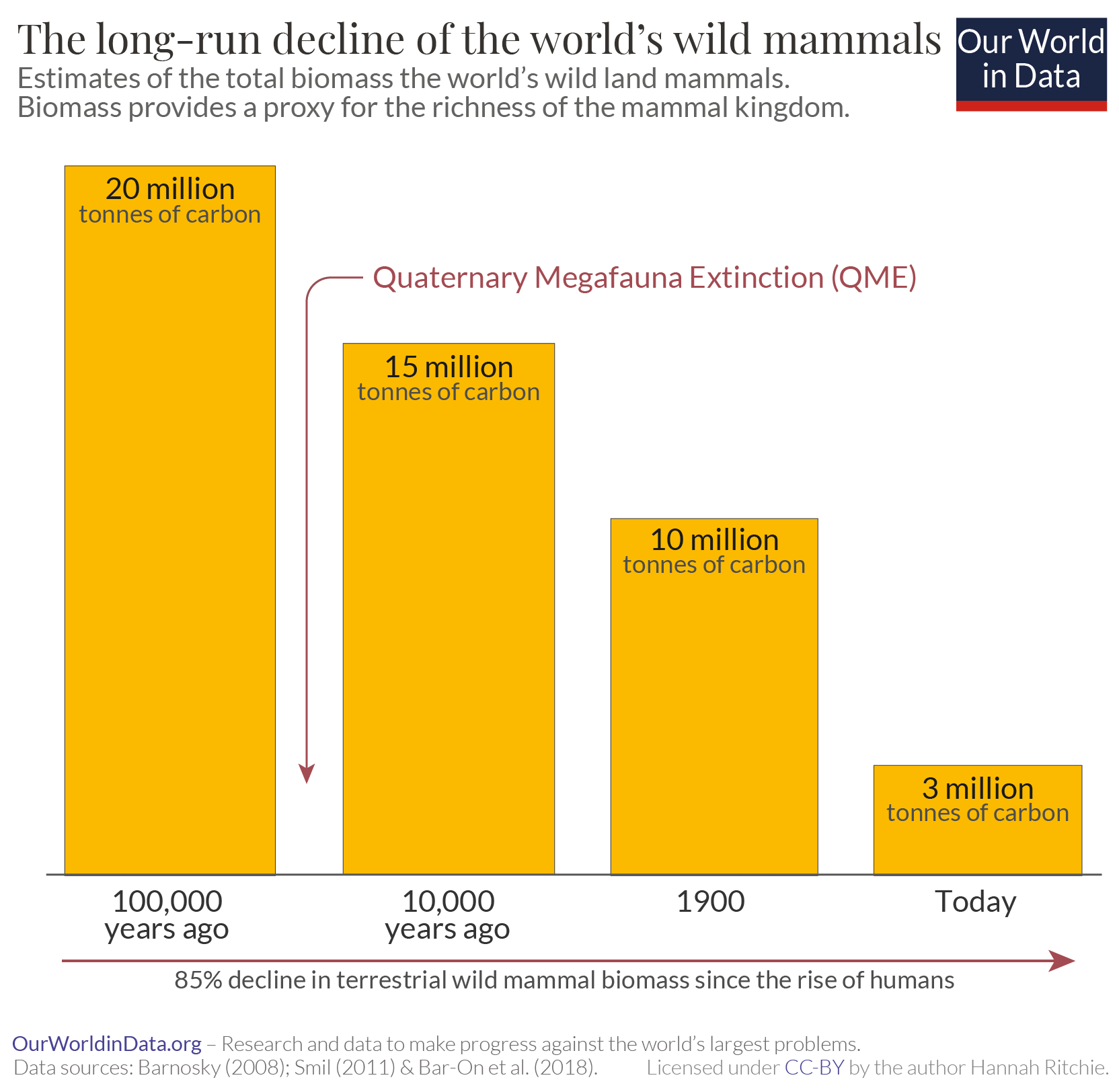

I have reconstructed the long-term estimates of mammal terrestrial biomass from 100,000 BC through to today from various scientific sources. 2 This means biomass from marine mammals – mainly whales – is not included. The story of whaling is an important one that I cover separately here. This change in wild land mammals is shown in the chart. When I say ‘wild mammals’ from this point, I’m talking about our metric of biomass.

If we go back to around 100,000 years ago – a time when there were very few early humans and only in Africa – all of the wild land mammals on Earth summed up to around 20 million tonnes of carbon. This is shown as the first column in the chart. The mammoths, and European lions, and ground sloths were all part of this.

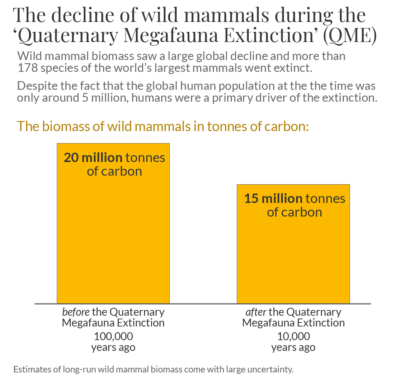

By around 10,000 years ago we see a huge decline of wild mammals. This is shown in the second column. It’s hard to give a precise estimate of the size of these losses millennia ago, but they were large: likely in the range of 25% to 50%. 3

It wasn’t just that we lost a lot of mammals. It was almost exclusively the world’s largest mammals that vanished. This big decline of mammals is referred to as the Quaternary Megafauna Extinction (QME). The QME led to the extinction of more than 178 of the world’s large mammals (‘megafauna’).

Many researchers have grappled with the question of what caused the QME. Most evidence now points towards humans as the primary driver. 4 I look at this evidence in much more detail in a related article. Most of this human impact came through hunting. There might also have been smaller local impacts through fire and other changes to natural landscapes. You can trace the timing of mammal extinctions by following human expansion across the world’s continents. When our ancestors arrived in Europe the European megafauna went extinct; when they arrived in North America the mammoths went extinct; then down to South America, the same.

What’s most shocking is how few humans were responsible for this large-scale destruction of wildlife. There were likely fewer than 5 million people in the world. 5 Around half the population of London today. 6

A global population half the size of London helped drive tens to hundreds of the world’s largest mammals to extinction. The per capita impact of our hunter-gatherer ancestors was huge.

The romantic idea that our hunter-gatherer ancestors lived in harmony with nature is deeply flawed. Humans have never been ‘in balance’ with nature. Trace the footsteps of these tiny populations of the past and you will find extinction after extinction after extinction.

Hunting to farming: how human populations now compete with wild mammals

We’re now going to fast-forward to our more recent past. By the year 1900, wild mammals had seen another large decline.

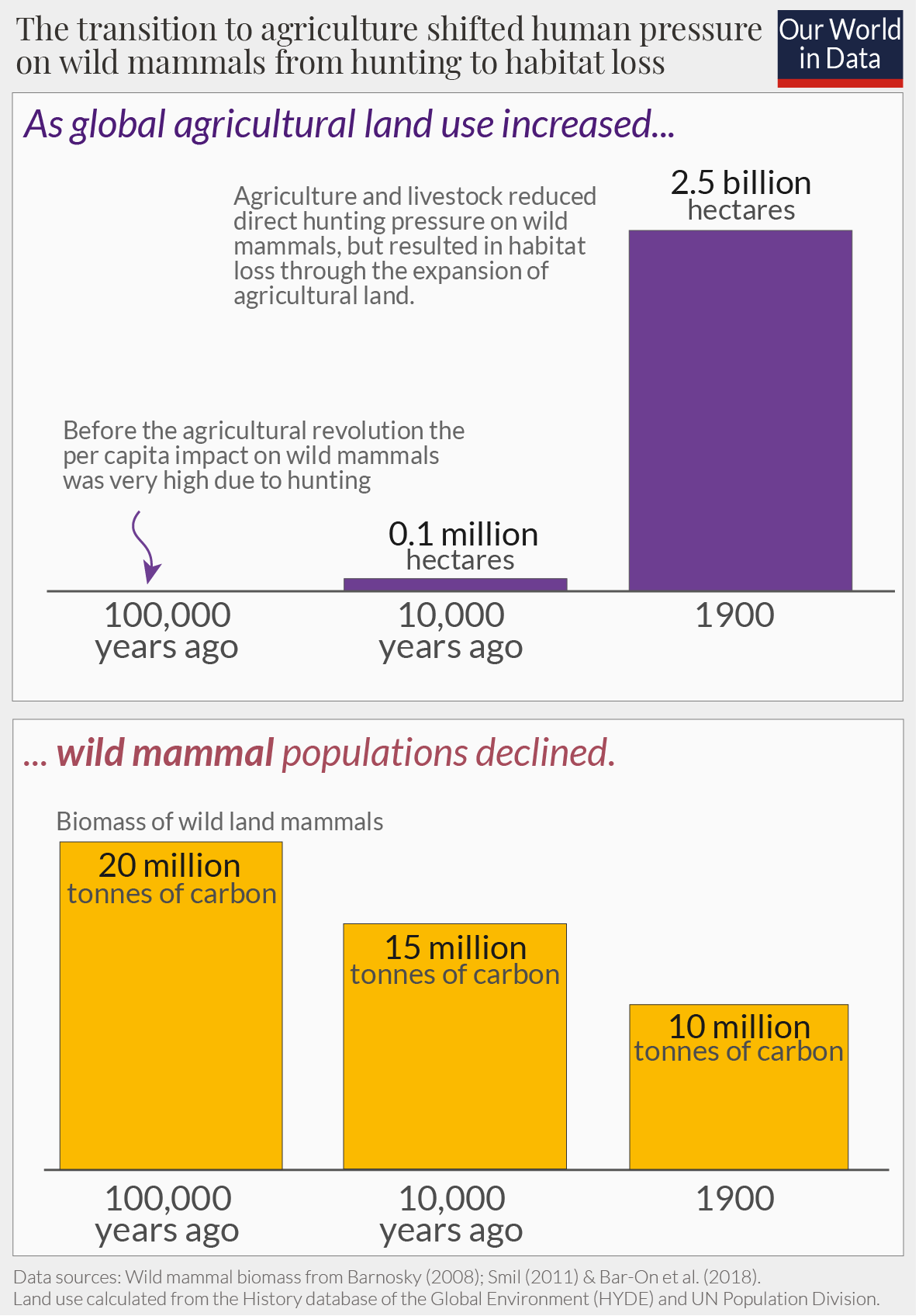

By this point, the pressures on wild mammals had shifted. The human population had increased to 1.7 billion people. But the most important change was the introduction of farming and livestock. We see this in the top panel of the chart. This shows the per capita agricultural land use over these millennia – a reflection of how humans got their food. 7 Before the agricultural revolution around 10,000 years ago, our food came from hunting and gathering. Agricultural land use was minimal although as we’ve already seen, per capita impacts were still high through hunting. We then see a clear transition point, where agricultural land use begins to rise.

The rise of agriculture had both upsides and downsides for wild mammals. On the one hand, it alleviated some of the direct pressure. Rather than hunting wild mammals we raised our own for meat, milk, or textiles. In this way, the rise of livestock saved wildlife. Crop farming also played a large role in this. The more food humans could produce for themselves, the less they needed to rely on wild meat.

But the rise of agriculture also had a massive downside: the need for agricultural land meant the loss of wild habitats.

The expansion of agriculture over millennia has completely reshaped the global landscape from one of wild habitats, to one dominated by farms. Over the last 10,000 years, we’ve lost one-third of the world’s forests and many grasslands and other wild habitats have been lost too. This obviously came at a large ecological cost: rather than competing with wild mammals directly, our ancestors took over the land that they needed to survive.

We see this change clearly in the bottom panel of the chart: there was a first stage of wild mammal loss through hunting; then another decline through the loss of habitats to farmland.

This shift in the distribution has continued through to today. We see this in the final column, which gives the breakdown in 2015. Wild mammals saw another large decline in the last century. At the same time the human population increased, and our livestock even more so. This is because incomes across the world have increased, meaning more people can afford the meat products that were previously unavailable to them. We dig a bit deeper into this distribution of mammals in a related article.

The past was a zero-sum game; the future doesn’t have to be

Since the rise of humans, wild land mammals have declined by 85%.

As we just saw, this history can be divided into two stages. The pre-agriculture phase where our ancestors were in direct competition with wild mammals. They killed them for their meat. And the post-agriculture phase where the biggest impact was indirect: habitat loss through the expansion of farmland. Our past relationship with wild animals has been a zero-sum game: in one way or another, human success has come at the cost of wild animals.

How do we move forward?

Some people suggest a return to wild hunting as an alternative to modern, intensive farming. A return to our primal roots. This might be sustainable for a few local communities. But we only need to do a simple calculation to see how unfeasible this is at any larger scale. In 2018 the world consumed 210 million tonnes of livestock meat from mammals [we’re only looking at mammals here so I’ve excluded chicken, turkey, goose, and duck meat]. In biomass terms, that’s 31 million tonnes of carbon. 8 From our chart above we saw that there are only 3 million tonnes of wild land mammal biomass left in the world. If we relied on this for food, all of the world’s wild mammals would be eaten within a month. 9

We cannot go back to this hunter-gatherer way of living. Even a tiny number of people living this lifestyle had a massive negative impact on wildlife. For a population of almost 8 billion it’s simply not an option.

But the alternative of continued growth in livestock consumption is also not sustainable. In the short term, it is saving some wild mammals from hunting. But its environmental costs are high: the expansion of agricultural land is the leading driver of deforestation, it emits large amounts of greenhouse gases, and needs lots of resource inputs.

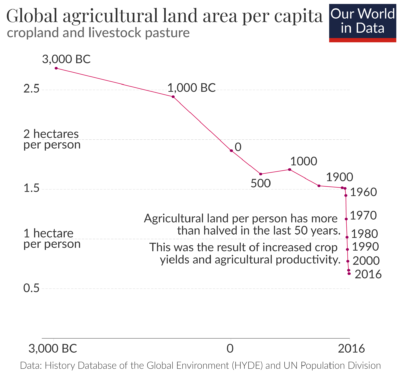

Thankfully we have options to build a better future. If we can reduce agricultural land – and primarily land use for livestock – we can free up land for wild mammals to return. There are already positive signs that this is possible. In the chart we see the change in per capita agricultural land use from 5,000 years ago to today. 10 Land use per person has fallen four-fold. The most dramatic decline has happened in the last 50 years: the amount of agricultural land per person has more than halved since 1960. This was the result of increased crop yields and livestock productivity. Of course, the world population also increased over that time, meaning total agricultural land use continued to grow. But, there might be positive signs: the world may have already passed ‘peak agricultural land’. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization reports a decline in global agricultural land since 2000: falling from 4.9 to 4.8 billion hectares. A very small decline, but signs that we could be at a turning point.

I’ve tried to capture what the future could look like in this final chart. It shows the rise in global agricultural land use over these millennia and the decline in wild biomass that we’ve already seen. But looking to the future, a decline in agricultural land alongside a rise in wild mammals is possible. How can we achieve this?

Some people are in favor of a switch to traditional plant-based diets: cereals, legumes, fruits, and vegetables. Because the land use of plant-based diets is smaller than meat-based diets this is definitely a sustainable option; those who adopt such diets have a low environmental footprint. But many people in the world just really like meat and for those that can afford it, it’s a central part of their diet. For many of those who can’t aspire to be able to do so; we see this when we look at how meat consumption rises with income.

With new technologies it’s possible to enjoy meat or meat-like products without raising or consuming any animals at all. We can have our cake and eat it; or rather, we can have our meat and keep our animals too. Food production is entering a new phase where we can move meat production from the farm to the lab. The prospects for cultured meat are growing. In 2020, Singapore was the first country to bring lab-grown chicken to the market. And it’s not just lab-grown meat that’s on the rise. A range of alternative products using other technologies such as fermentation or plant-based substitutes are moving forward: Beyond Meat, Quorn and Impossible Foods are a few examples.

The biggest barriers – as with all technologies in their infancy – is going to be scale and affordability. If these products are to make a difference at a global scale we need to be able to produce them in large volumes and at low cost. This is especially true if we want to offer an alternative to the standard ‘wild animal to livestock’ transition for lower-income countries. They have to be cheaper than meat.

It’s going to be a challenge. But it’s an incredibly exciting one. For the first time in human history we could decouple human progress from ecological degradation. The game between humans and wild animals no longer needs to be zero-sum. We can reduce poaching and restore old habitats to allow wild mammals to flourish. Doing so does not have to come at the cost of human wellbeing. We can thrive alongside, rather than compete with, the other mammals that we share this planet with.

Quaternary Megafauna Extinctions

Humans have had such a profound impact on the planet’s ecosystems and climate that Earth might be defined by a new geological epoch: the Anthropocene (where “anthro” means “human”). Some think this new epoch should start at the Industrial Revolution, some at the advent of agriculture 10,000 to 15,000 years ago. This feeds into the popular notion that environmental destruction is a recent phenomenon.

The lives of our hunter-gatherer ancestors are instead romanticized. Many think they lived in balance with nature, unlike modern society where we fight against it. But when we look at the evidence of human impacts over millennia, it’s difficult to see how this was true.

Our ancient ancestors drove more than 178 of the world’s largest mammals (‘megafauna’) to extinction. This is known as the ‘Quaternary Megafauna Extinction’ (QME). The extent of these extinctions across continents is shown in the chart. Between 52,000 and 9,000 BC, more than 178 species of the world’s largest mammals (those heavier than 44 kilograms – ranging from mammals the size of sheep to elephants) were killed off. There is strong evidence to suggest that these were primarily driven by humans – we look at this in more detail later.

Africa was the least hard-hit, losing only 21% of its megafauna. Humans evolved in Africa, and hominins had already been interacting with mammals for a long time. The same is also likely to be true across Eurasia, where 35% of megafauna were lost. But Australia, North America and South America were particularly hard-hit; very soon after humans arrived, most large mammals were gone. Australia lost 88%; North America lost 83%; and South America, 72%.

Far from being in balance with ecosystems, very small populations of hunter-gatherers changed them forever. By 8,000 BC – almost at the end of the QME – there were only around 5 million people in the world. A few million killed off hundreds of species that we will never get back.

Did humans cause the Quaternary Megafauna Extinction?

The driver of the QME has been debated for centuries. Debate has been centered around how much was caused by humans and how much by changes in climate. Today the consensus is that most of these extinctions were caused by humans.

There are several reasons why we think our ancestors were responsible.

Extinction timings closely match the timing of human arrival. The timing of megafauna extinctions were not consistent across the world; instead, the timing of their demise coincided closely with the arrival of humans on each continent. The timing of human arrivals and extinction events is shown on the map.

Humans reached Australia somewhere between 65 to 44,000 years ago. 11 Between 50 and 40,000 years ago, 82% of megafauna had been wiped out. It was tens of thousands of years before the extinctions in North and South America occurred. And several more before these occurred in Madagascar and the Caribbean islands. Elephant birds in Madagascar were still present eight millennia after the mammoth and mastodon were killed off in America. Extinction events followed man’s footsteps.

Significant climatic changes tend to be felt globally. If these extinction were solely due to climate we would expect them to occur at a similar time across the continents.

QME selectively impacted large mammals. There have been many extinction events in Earth’s history. There have been five big mass extinction events, and a number of smaller ones. These events don’t usually target specific groups of animals. Large ecological changes tend to impact everything from large to small mammals, reptiles, birds, and fish. During times of high climate variability over the past 66 million years (the ‘Cenozoic period’), neither small nor large mammals were more vulnerable to extinction. 12

The QME was different and unique in the fossil record: it selectively killed off large mammals. This suggests a strong influence from humans since we selectively hunt larger ones. There are several reasons why large mammals in particular have been at greater risk since the arrival of humans.

Islands were more heavily impacted than Africa. As we saw previously, Africa was less-heavily impacted than other continents during this period. We would expect this since hominids had been interacting with mammals for a long time before this. These interactions between species would have impacted mammal populations more gradually and to a lesser extent. They may have already reached some form of equilibrium. When humans arrived on other continents – such as Australia or the Americas – these interactions were new and represented a step-change in the dynamics of the ecosystem. Humans were an efficient new predator.

There has now been many studies focused on the question of whether humans were the key driver of the QME. The consensus is yes. Climatic changes might have exacerbated the pressures on wildlife, but the QME can’t be explained by climate on its own. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors were key to the demise of these megafauna.

Human impact on ecosystems therefore date back tens of thousands of years, despite the Anthropocene paradigm that is this a recent phenomenon. We’ve not only been in direct competition with other mammals, we’ve also reshaped the landscape beyond recognition. Let’s take a look at this transformation.

30 Examples of Mammals (With Pictures)

Animals in the class Mammalia, or mammals are arguably some of the more complex animals in the animal kingdom. Humans are mammals after all! Mammals are different from other types of animals and are warm blooded, fur/hair bearing, milk producing animals. In this article, we will cover several examples of mammals.

But first, let’s learn a little bit more about what it means to be a mammal.

What is a mammal?

Class: Mammalia

A mammal is a warm-blooded vertebrate that breathes air. Most mammals are terrestrial, often have fur or hair, and have more complex brains than other types of animals. Mammals nurse their babies and almost always give birth to live young, but there are some exceptions.

There are an estimated 130 billion mammals throughout the world today. Mammals and birds are the only warm blooded vertebrates on the planet. The largest mammal on earth, the blue whale, is on this list of examples of mammals.

30 examples of mammals

1. Dog

Scientific name: Canis lupus familiarlis

In addition to ourselves, many of us have a mammal or two living in our house! Dogs, descended from wolves, are common house pets in households virtually all over the world. Dogs make great pets due to their affinity for human companionship and intelligence.

2. Raccoon

Scientific name: Procyon lotor

Known for their love of raiding trash cans and dumpsters, Raccoons are also very smart and quick witted mammals. Raccoons are found throughout most of North America. These adorable little furry creatures can have quite the attitude and can make an alarming growling sound when agitated.

3. Virginia Opossum

Scientific name: Didelphis virginiana

The Virginia Opossum more commonly referred to as just opossum can be found throughout most of Eastern America as well as along the Western coast of the US. Virginia Opossums are America’s only marsupial and carry their babies in a pouch. Once the babies grow to be a bit bigger, mother opossums will carry them on their backs- sometimes carrying a half dozen or more!

4. Moose

Scientific name: Alces alces

Moose fall into the same taxonomic superfamily as deer, making them the largest and heaviest species of deer. Despite their large size, these giants are strictly vegetarians and eat both terrestrial and aquatic vegetation. Moose roam the northern hemisphere and can be found in Canada and Northern US, as well as Northern Europe and Asia.

5. Blue Whale

Scientific name: Balaenoptera musculus

Most people associate mammals with being land-dwelling animals, but that is not always the case. The Blue Whale is actually the largest mammal in the world, sometimes growing up to 100 feet long! Blue Whales live in all oceans aside from the Arctic ocean.

6. Flying Fox

Scientific name: Pteropus spp.

Flying isn’t just for birds, but mammals too! There are several species of Flying Fox, which are very large, frugivorous fruit eating bats. Bats are one of the few examples of mammals that can fly. They get their name from the rusty, fox-colored fur on their chest. Flying Foxes are distributed throughout Asia, Australia and East Africa.

7. American black bear

Scientific name: Ursus americanus

The American black bear can be found throughout much of, you guessed it, America as well as almost entirely throughout Canada. Despite these bears being found in similar ranges to Grizzly Bears and Polar Bears, they are actually more closely related to bear species found in Asia.

8. Lion

Scientific name: Panthera leo

The Lion, an iconic animal in the animal kingdom as well as in the Disney franchise, is known for being an apex predator. These giant cats will chase down their prey with ease, however most of the hunting is left to the females. Lions are found scattered throughout Africa outside of the Saharan desert.

9. Hippopotamus

Scientific name: Hippopotamus amphibious

The Hippopotamus, also referred to as the Hippo, is arguably one of the world’s most dangerous animals. They are known to have a fierce temper and little patience when it comes to people getting too close to them. Hippos have been impacted by habitat loss and are found in small, scattered distributions throughout Subsaharan Africa near rivers and water bodies.

10. Coyote

Scientific name: Canis latrans

Coyotes are a close relative to Wolves but are certainly a lot more common than their relatives. They are found virtually all throughout North America and are considered to be niche generalists due to the fact that they can adapt to almost anywhere and they are not picky eaters! Coyotes have even managed to find a home in busy cities.

You may also like:

11. Asian Elephant

Scientific name: Elephas maxima

The Asian Elephant is slightly smaller than it’s African relatives. Asian Elephants are endangered and have sadly been heavily impacted by deforestation and habitat loss. These elephants are native to India and Southeast Asia however their populations are shrinking. Elephants live in herds and are very protective of their families.

12. Harbor Seal

Scientific name: Phoca vitulina

The Harbor Seal, otherwise known as the Common Seal, is a species of pinniped that is widely distributed along coastlines in the Northern Hemisphere. Harbor Seals can be found in the Atlantic, Pacific, Baltic and North Seas. They can often be found in large groups laying out on rocky patches along the coast.

13. North American Beaver

Scientific name: Castor canadensis

The North American Beaver is actually a large semi-aquatic rodent, only somewhat distantly related to other species of rodents like rats and gophers. These Beavers are found in riparian areas all throughout Canada, America and even northern Mexico. They are the state mammal of both Oregon and New York.

14. White-tailed Deer

Scientific name: Odocoileus virginianus

The most common type of deer and more commonly spotted mammals in the United States is the White-tailed deer. However, this species can also be found in central and northern South America and they have also been introduced to New Zealand as well as the Caribbean and parts of Europe. They are well adapted to living in all sorts of habitats and conditions.

15. Koala

Scientific name: Phascolarctos cinereus

The Koala, also known as the Koala Bear is not actually related to bears at all but is instead a marsupial found in Australia. These cute, furry creatures carry their young in a pouch for several months after giving birth. They live a very lazy lifestyle and may sleep up to 20 hours per day! These animals are true herbivores.

16. White Rhinocerous

Scientific name: Ceratotherium simum

The White Rhinoceros or Rhino is the largest species of Rhino. There are actually two sub-species, the Northern White Rhino and Southern White Rhino. The Northern subspecies is incredibly rare and there are very few individuals left due to excessive poaching. White Rhinos are found mostly in the southern tip of Africa.

17. Bottlenose Dolphin

Scientific name: Tursiops truncatus

Bottlenose Dolphins are beloved marine mammals known for their intelligence and social nature. They are found in warm, tropical and temperate waters all around the world. Due to their smarts, the military has managed to train Bottlenose Dolphins to locate underwater mines.

18. Silverback Gorilla

Scientific name: Gorilla gorilla beringei

Gorillas are one of my favorite examples of mammals. These great apes are well-known by animal lovers but are actually the rarest and most endangered species of Gorilla. They inhabit forests and rainforests in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda and Rwanda. Unfortunately, Silverbacks are threatened by poachers and habitat loss.

19. North American Porcupine

Scientific name: Erethizon dorsatum

Only second in size to the North American Beaver, the North American Porcupine is a large rodent found in North America. They are infamous for their large quills or spines that help deter predators. These rodents are most commonly found in mixed or coniferous forests.

20. Prairie Dog

Scientific name: Cynomys spp.

There are actually five species of Prairie Dog, all of which are found in North America. Prairie Dogs are technically a type of Ground Squirrel and live in more arid areas in the Western and Southwestern United States as well as Mexico. They are incredibly social animals and form large colonies.

21. Three-toed Sloth

Scientific name: Bradypus spp.

Three-toed sloths are arboreal mammals found in tropical forests in Central and South America. They are incredibly slow moving, chugging along at a measly 0.15 miles per hour! Despite spending most of their time up in the trees, Three-toed sloths are actually great swimmers.

22. Polar Bear

Scientific name: Ursus maritimus

The Polar Bear is a large species of bear, well-known for surviving the harsh environment of the Arctic circle. Their white fur allows for them to blend in with the ice and snow in the tundra. Climate change is likely at least partially to blame for decreasing populations due to ice loss, meaning the bears have to swim further and further between ice masses.

23. Tiger

Scientific name: Panthera tigris

Tigers, the largest cat species in the world, are fierce predators that roam the forests and jungles of India and Southeast Asia. They are easily recognized by their black stripes on bright, orange fur. Tiger populations are rapidly declining due to habitat loss and poaching. Tigers are considered an apex predator within their ecosystem and play a vital role in maintaining the population of their prey.

24. Platypus

Scientific name: Ornithorhynchus anatinus

When it comes to mammals, Platypuses are certainly the odd ones out. They have a duck shaped beak or bill, they give birth by laying eggs, and they are actually venomous! Male platypus have a spur on their back foot that they can use to envenomate predators. These odd creatures are found near water bodies in Eastern Australia, New Zealand and Tasmania.

25. Chipmunk

Scientific name: Tamias striatus

Chipmunks are adorable, pocket-sized mammals that can be found all throughout the Eastern United States and Southern Canada. They live in wooded areas, but are also able to survive in more suburban or urban areas. They have flexible cheek pouches that allow them to stuff their face full of nuts, seeds, fruits and insects.

26. Snowshoe Hare

Scientific name: Lepus americanus

The Snowshoe Hare is a species of rabbit named after it’s extremely large back legs that act as snowshoes to prevent them from sinking down into deep snow. They are found in in temperate regions in the United States as well as Canada where they prefer boreal forests with plenty of cover on the ground in the form of shrubs and bushes.

27. Red Fox

Scientific name: Vulpes vulpes

The Red Fox is a widely distributed mid-sized omnivore. There are 45 subspecies of Red Fox that are found in Asia, Africa, Europe, North America and they have even been introduced in Australia. These animals are incredibly adaptable and can thrive in a diverse range of habitat types. In fact, Red Foxes are incredibly common in the busy city of London.

28. Ring-tailed Lemur

Scientific name: Lemur catta

If you have seen the popular children’s movie Madagascar, then you are most likely familiar with the Ring-tailed Lemur, aptly named for the black rings down their tail. These primates are incredibly social animals and form groups are large as 30 individuals strong. Like all other Lemurs, they are only found in Madagascar.

29. Reindeer

Scientific name: Rangifer tarandus

The Reindeer, also known as Caribou, is not just a character in Christmas stories but is a real animal found in polar regions of North America, Europe and Asia. They are related to other ungulates like Moose or Deer. Reindeer travel in large herds and often make long migrations each year.

30. Killer Whale

Scientific name: Orcinus orca

Killer Whales, or Orcas are actually more closely related to dolphins than other whales. They are excellent hunters and will work with other individuals to take down prey. Killer Whales have been known to hunt sea birds, other marine mammals like seals, dolphins and other whales, and even terrestrial mammals that venture close to the shore. They are found virtually throughout all oceans and seas.

Related Posts:

About Samantha S.

Samantha is a wildlife biologist with a masters degree in environmental biology. Most of her work has been with reptiles, however she has also worked with birds and marine organisms as well. She enjoys hiking, snorkeling, and looking for wildlife.

English Online

Mammals

A mammal is an animal that feeds its babies with milk when it is young. There are over 4,500 types of mammals. Many of the most popular animals we know are mammals, for example, dogs, cats, horses, cows, but exotic animals like kangaroos, giraffes, elephants and anteaters belong to this group, too. Humans are also mammals.

Mammals live in all regions and climates. They live on the ground, in trees or underground. Polar bears, reindeer and seals are mammals that live in the Arctic regions. Others, like camels or kangaroos prefer the world’s dry areas. Seals and whales are mammals that swim in the oceans; bats are the only mammals that can fly.

Mammals have five features that make them different from other animals:

People have hunted mammals for ages. They ate their food and made clothes out of their skins. Thousands of years ago wild mammals were domesticated and gave human beings milk, wool and other products. Some mammals, like elephants and camels are still used to transport goods. In poorer countries farmers use cows or oxen, to plough fields.

Today some mammals are hunted illegally. Whales are killed because people want their meat and oil, elephants are killed for the ivory of their tusks.

Mammals are often kept as pets. Among them are cats, dogs, rabbits or guinea pigs.

Mammals are useful to people in many other ways. Some help plants grow and eat harmful insects. Others eat weeds and prevent them from spreading too far. The waste of mammals is used as fertilizers that improve the quality of soil.

Types of mammals

Mammals are divided into three groups:

Mammals and their bodies

Skin and hair cover a mammal’s body. Some mammals have horns, claws and hoofs. The hair or fur of a mammal has many functions. The colour often blends in with the world around them and allows them to hide from their enemies. Some mammals produce needles or sharp hair that protects them from attack. But the main function is to keep the body warm.

Mammals have glands that produce substances that the body needs like hormones, sweat and milk.

A mammal’s skeleton is made up of three parts:

Mammals have a four-chambered heart system that pumps blood into all parts of their body. The blood brings oxygen to muscles and tissue. The red blood cells of mammals can carry more oxygen than in many other animals. Because mammals have a high body temperature they must burn a lot of food.

Mammals digest food through their digestive system. After food is eaten through the mouth it goes down the throat into the stomach and passes through the intestines. Mammals that eat plants have a complicated system with long intestines that help break down food. Flesh is easier to digest so meat-eating mammals have a simpler stomach.

Mammals breathe air through their lungs. Most of them have noses or snouts with which they take in air. Dolphins and whales breathe through a hole in the top of their back.

Mammals and their senses

Mammals have five senses that tell them what is happening in their surroundings. Not all senses are developed equally among mammals.

Mammals rely on smell to find food and warn them of their enemies. Many species use smell to communicate with each other. Humans, apes and monkeys have a relatively bad sense of smell.

Taste helps mammals identify the food that they eat. Most mammals have a good sense of hearing. Some mammals use their hearing to detect objects in the dark. Bats, for example, use sounds to navigate and detect tiny insects. Dolphins also use such a system to find their way around.

While higher primates, like humans, apes and monkeys have a highly developed sense of sight other mammals are nearly blind. Most of these mammals, like bats, are active at night.

Mammals have a good sense of touch. They have nerves on all parts of their body that let them feel things. Cats and mice have whiskers with which that they can feel themselves around in the dark.

What mammals eat

Herbivores are mammals that eat plants. They have special teeth that allow them to chew food better. Examples of herbivores are deer, cows and elephants. The giant panda is a plant eater that only eats bamboo.

Carnivores are mammals that eat other animals. Cats, dogs, tigers, lions, wolves belong to this group. They are hunters that tear their prey apart with sharp teeth. They do not chew their food very much.

How mammals move

Most mammals live and move on the ground. They have four legs and walk by lifting one foot at a time or by trotting. Kangaroos hop and use their tail for balancing.

Mammals that live in forests spend a lot of their time in trees. Monkeys can grasp tree branches with claws and can hang on to them with their curved tail. Often mammals spend time hanging upside down in trees.

Dolphins and whales are mammals that live and move around in water. Instead of limbs they have flippers which they use to move forward. Other animals, like the hippopotamus, only spend some time in the water.

Bats are the only flying mammals. Their wings are made of skin stretched over their bones. They can fly by beating their wings up and down.

Gophers and moles are mammals that spend most of their life underground.

How mammals have babies

Mammals reproduce when a male’s sperm gets into contact with a female egg and fertilizes it. A young mammal grows inside the female’s body. Before this can happen mammals mate. Males and females stay together for a certain time.

Unborn mammals live their mother’s body for different periods of time. While hamsters are born after only 16 days, it takes elephants 650 days to give birth. Human pregnancies last about 9 months.

Many new-born mammals, like horses and camels, can walk and run shortly after they are born.

After birth the glands of a female mammals produce milk. Some mammals nurse their babies for only a few weeks. Others, for example elephants, give milk to their babies for a few years.

The duck-billed platypus and echidnas are the only mammals that lay eggs. After the young hatch they drink milk from their mother, just like other mammals do.

Life habits

Many mammals migrate during special times of the year in order to get food and survive. North American bats travel to the south because insects become scarce during the cold winter months. Zebras and other wild animals follow the rainy seasons in Africa to find green grass. Whales migrate to warmer southern waters off the coast of Mexico to give birth to babies because they could not survive in the cold waters of the Arctic Ocean.

Some mammals hibernate because they cannot find enough food to survive. Their body temperature falls, heartbeat and breathing become slower. During this period hibernating mammals do not eat. They live from the fat of their bodies. Bats, squirrels and other rodents hibernate.

Mammals defend themselves from attackers in many ways. Hoofed mammals can run quickly in order to get food or escape. Squirrels rush into trees to hide. Some animals have special features that protect them from enemies. Skunks spray a bad smelling liquid to keep off attackers. The fur of mammals sometimes changes with its surroundings. Arctic foxes, for example, are brown in summer and in the winter their coats turn white.

Squirrel eating a peanut by DAVID ILIFF

History of mammals

Today, some species are in constant danger of becoming extinct because they are hunted by humans. Hunters and poachers earn money by selling fur, tusks and other parts of mammals. Larger wild animals are often brought to zoos where they are protected.