What is your attitude to the torture a criminal

What is your attitude to the torture a criminal

Penal Code 206 PC – The Crime of “Torture” in California

California Penal Code 206 PC defines the crime of torture as

The exact language of the code section states that:

206. Every person who, with the intent to cause cruel or extreme pain and suffering for the purpose of revenge, extortion, persuasion, or for any sadistic purpose, inflicts great bodily injury as defined in Section 12022.7 upon the person of another, is guilty of torture.

The crime of torture does not require any proof that the victim suffered pain.

Examples

Defenses

A defendant can raise a legal defense to challenge an allegation under this statute. Some defenses include the accused showing that:

Penalties

A violation of this statute is a felony. This is opposed to a California misdemeanor or an infraction.

The crime is punishable by life in state prison, with the possibility of parole.

Note that 18 U.S.C. 2340 is the federal statute on torture. It is known as the “Torture Act.”

Our California criminal defense attorneys will explain the following in this article:

A person commits torture by inflicting great bodily injury to cause the victim extreme pain or suffering.

1. How does California law define the crime of torture?

The definition of torture under California Penal Code 206 is when:

A person can commit this violent crime by either:

“Great bodily injury” means significant or substantial physical injury, such as broken bones. It is not required, though, that a victim actually suffer pain for a person to be guilty of torture. 3

Note that someone acts for the purpose of extortion if he or she intends to:

Note too that someone acts with a sadistic purpose if he or she intends to:

Unlike murder, this offense does not require that the defendant act with premeditation. 6

2. Are there defenses to Penal Code 206 PC?

Defense lawyers draw on several legal strategies to attack torture charges under these criminal laws. These include showing that:

2.1 No criminal purpose

A defendant cannot be guilty of torture unless he/she acted with the purpose of:

It is a defense, then, for the defendant to show that he/she did not act with any of these goals.

2.2 Insanity

An accused can always assert an insanity defense to torture. The law says a person is insane if:

If successful, the defense results in the accused being admitted to a state facility for treatment.

2.3 Self-defense

A defendant can try to beat a charge by saying that he acted in self-defense.

This defense will work if the accused:

Torture is a felony offense that can lead to life in prison, if convicted.

3. What is the punishment for torture in California?

Torture under California Penal Code section 206 is a felony offense. The crime is punishable by a life sentence in state prison, with the possibility of parole.

Note that the reason for the severe sentencing is:

4. Does this lead to deportation?

A conviction under this statute will have negative immigration consequences.

A violation of PC 206 is both:

These results mean that a non-citizen defendant convicted of the offense can be either:

5. Can a person get a conviction expunged?

A person cannot get an expungement if convicted of this crime.

As a general rule, expungements are not available for convictions resulting in prison terms.

Torture is also a federal offense if committed outside the U.S.

6. Are there federal torture laws?

18 U.S.C. 2340 is the federal statute on torture. It is known as the “Torture Act.”

Under this law, it is a crime if:

Note that acts of torture committed within the U.S. are charged under state laws.

A person convicted under this law can face up to 20 years in prison. If a defendant killed someone in the act of torture, then he/she can be punished with:

7. What is the Convention against Torture?

The “Convention against Torture” is also known as the United Nations Convention against Torture (UNCAT).

UNCAT is an international agreement among countries that seeks to prevent:

The Convention mandates that countries have laws in effect that prevent torture.

8. Are there related offenses?

There are three crimes related to torture. These are:

8.1 Mayhem – PC 203

Penal Code 203 PC is the California statute that defines “mayhem.” This crime is defined as the act of maliciously doing any of the following to another person:

Aggravated mayhem consists of intentionally causing someone:

8.2 Aggravated battery – PC 243d

Penal Code 243d PC is the statute that defines the crime of aggravated battery. This offense is also known as “battery causing serious bodily injury.”

A person commits the crime when he/she:

Prosecutors may file this charge as a misdemeanor or a felony.

8.3 Corporal injury on an intimate partner – PC 273.5

California Penal Code 273.5 PC makes it a crime to inflict “corporal injury” on a spouse or cohabitant.

“Corporal injury” means any physical injury, whether serious or minor.

The crime is also commonly referred to as:

For additional help…

Contact our law firm for a free consultation.

For additional guidance or to discuss your case with a criminal defense lawyer, we invite you to contact us at Shouse Law Group. We are based in Los Angeles County but create attorney-client relationships throughout the state, including San Bernardino County, Pomona, Pasadena, Long Beach, Torrance, Glendale, and more.

Legal References:

California Penal Code Blog Posts:

‘Torture’ in Criminal Law: Legal Norms and Standards of Judicial Review

Source: Roberto Ferrari/Flickr

Intentional excessive suffering which an individual experiences against their will and cannot independently stop…

(a definition of ‘torture’)

The epigraph above does not sound like technical legal language. Some might find it slightly ‘literary’ while others will not immediately understand it to mean torture or cruel and inhuman treatment. This is why it is so important to understand exactly what Russian human rights defenders mean when they refer to a ‘torture colony’ or conditions of detention ‘amounting to torture’.

There are not so many principles in international human rights law which are absolute and therefore cannot and should not be disputed. One of the few principles rarely or never questioned is the prohibition of torture and cruel and inhuman treatment or punishment, in particular by agents of the State. This maxim of law is established in leading paragraphs of all international human rights covenants and conventions and underlies a large part of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR, Court) case-law concerning violations of Art. 3 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights (ECHR) and of the work of specialised committees against torture at the global and European levels.

This may be the reason why human rights defenders and lawyers focus so much on investigating any violations of this absolute prohibition and on preventing the impunity of perpetrators of this ‘modern barbarism,’ committed either on behalf of the State or with its quasi-silent acquiescence. Perhaps there is only one pervasive situation in which the absolute ban on torture and ill-treatment has been questioned—the fight against the new world evil: terrorism (typical examples include Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib prisons), but even in this case, doubts as to possible legitimacy of torture only arise in regard of individuals clearly dangerous in terms of perpetrating massive crimes against humanity.

Going back to legal regulations designed to counteract torture, there is one aspect involved which few people are likely to dispute—at least, it was not challenged by the participants of an expert roundtable meeting on the issue held on 1 September 2017 in Moscow. I am referring to the preliminary conclusion from the meeting, formulated in the following way by Professor Gennady Esakov:

“The problem of torture in Russia is not so much a legal matter as it is a social one. We have an effective instrument in place for prosecuting torture (which can be slightly adjusted if needed), but there is no desire whatsoever to investigate and prosecute torture whether it is perpetrated ‘on behalf of the State’ or by private individuals. This problem is social, administrative and psychological in nature. Its legal aspect is limited.”

It would seem that by accepting this statement, we must agree that a further discussion of the legal aspects of the issue does not make much sense. Also, according to an introduction to the subject made by Kristaps Tamužs, lawyer with the Constitutional Court of Latvia who has extensively worked in Strasbourg, the European Court of Human Rights has adopted an approach to cases under Article 3 of the ECHR which is somewhat different from the treatment of torture in national jurisdictions. Thus, according to the Court, “preventive mechanisms are more important than compensatory, as the former, first, reduce the likelihood of torture and second, serve the entire society and not just the individual victim of torture.”

Apparently, here we could end the introductory part, adding perhaps that practice, once again, seems more important than theory—except that there are numerous problems and uncertainties in the way torture is defined and addressed under different jurisdictions.

Let’s start with its definition in international human rights law. By referring to the core definition of ‘torture’ and related concepts, i.e. different subtypes of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (hereinafter this extended concept of torture is implied, unless otherwise stated), one can see that the way torture is interpreted by UN treaties and mechanisms is somewhat different from the legal position and practice of the ECtHR and certain Council of Europe States Parties.

So what exactly follows from the UN Convention Against Torture and other international legal standards, according, e.g., to the recommendations concerning their application provided in the authoritative resource, Combating Torture: A Manual for Judges and Prosecutors, published in the UK? The book highlights several aspects characterising torture, such as purpose, intent, perpetrator and, most importantly, what constitutes this prohibited form of violence against a person. The essential elements of torture include: (1) severe mental or physical pain or suffering; (2) intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining information or a confession; (3) by or at the instigation of, or with the consent or acquiescence of, a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.

Note an essential reservation made in the cited Manual, published under the auspices of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and written by lawyers of the University of Essex Human Rights Centre, namely that according to the authors, the concept of torture does not include pain or suffering “arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions” (!). It would seems that the cited clarifications and explanations are fairly specific and can assist law enforcers, judges and prosecutors in qualifying acts of violence committed by public officials. But is this approach really comprehensive?

This is what the legal expert mentioned above said regarding European law: “The definition in Article 3 of the ECHR is undoubtedly the broadest compared to relevant provisions of Article 1 of the UN Convention Against Torture and its interpretations mentioned above, and to the wording in the footnote to art. 117 of the Russian Criminal Code (see details below). Thus, Article 3 of the ECHR does not specify that torture can only be used by persons acting in an official capacity, nor does it require that the use of torture should have any purpose (such as forcing testimony). Moreover, the Court’s case law under Article 3 focuses mainly on the victim and the extent of suffering inflicted on them. Indeed, the main advantage of the absence of a precise definition of torture in the ECHR, according to Kristaps Tamužs, is that it enables a dynamic interpretation of the concept of ‘torture’ consistent with the Court’s evolving case law as well as changes in how torture is understood and defined under other international and domestic jurisdictions.

It would be appropriate to note that the moderator of the aforementioned roundtable in Moscow (and the author of this text) focused its agenda on the semantic differences revealed above in the discussion of the legal approaches to torture. In particular, one question proposed for discussion was whether law and enforcement practice should distinguish the following circumstances in which abuse occurs:

Apparently, there is a single answer to these questions: all of the above characteristics of torture are important for investigating incidents of unacceptable and illegitimate violence, but regardless of specific circumstances, the extent of suffering inflicted is at least as important as assigning the acts to certain categories, such as:

The Russian CC has two significant features in this regard.

First, ‘torture’ is part of a broader crime of ‘inflicting physical and mental suffering’ (istyazanye) (Article 117) defined in a footnote to the CC article with reference to the key characteristics of this criminal offence in the spirit of recommendations to the UN Convention.

This suggests that Russia’s criminal law does not prohibit torture per se but only provides for punishment of public officials for illegitimate use of violence while performing their official duties and for any adverse consequences thereof. In other words, this provision is about punishment for ‘excess of the performer’ rather than for breaching the absolute prohibition of torture under any circumstances!

In contrast, Latvia’s post-Soviet criminal law treats torture in an entirely different manner. Apparently, for a number of different reasons, legal and otherwise, the country’s legislation has evolved under a significant influence of the European Court’s case law. As a result, not only does it provide for a dedicated judicial ‘subsystem’ to handle citizens’ complaints against acts of the State and its officials (administrative proceedings), but ensures a thorough and impartial investigation of all torture cases brought against public officials in this jurisdiction. Equally noteworthy is the way Latvia’s effective Criminal Code takes into account the extent of harm and suffering caused to torture victims, as well as the purpose of torture 1 Latvia’s Criminal Code

Section 125(2)(4). Intentional Serious Bodily Injury

For a person who commits intentional infliction of such bodily injury as is dangerous to life or has been the cause of loss of vision, hearing or any other organs or functions of organs, or mental or other health disorder, if it is related to a general ongoing loss of ability to work to the extent of not less than one third, or has resulted in the termination of pregnancy, or has been manifested in irreparable facial disfigurement (serious bodily injury), if they have been in the nature of torment or torture, the applicable punishment is deprivation of liberty for a period of two and up to ten years, with or without probationary supervision for a period up to three years.

Section 126(2)(2). Intentional Moderate Bodily Injury

For a person who commits intentional infliction of such bodily injury as is not dangerous to life and has not resulted in the consequences provided for in Section 125 of this Law but has resulted in continued health disorder or general ongoing loss of ability to work to the extent of less than one third (moderate bodily injury), if they have been in the nature of torment or torture, the applicable punishment is the deprivation of liberty for a period of up to five years or temporary deprivation of liberty, or community service, or a fine, with or without probationary supervision for a period of up to three years.

Section 130(3)(2). Intentional Slight Bodily Injury

For a person who commits intentional infliction of slight bodily injury, if they have been in the nature of torment or torture, the applicable punishment is the deprivation of liberty for a period of up to three years or temporary deprivation of liberty, or community service, or a fine.

Section 130.1 Torture

For a person who commits torture, if such acts have not had the consequences provided for in Section 125, 126 or 130 of this Law, the applicable punishment is the deprivation of liberty for a period of up to one year or temporary deprivation of liberty, or community service, or a fine.

Section 272.1 (3). Compelling of False Explanations, Opinions or Translations at a Parliamentary Investigation Commission

For a person who commits illegal influencing for the purpose of achieving that a person shall give a false explanation, opinion or translation or refuses to give an explanation, opinion or translation to a parliamentary investigation commission, if they are related to torture, the applicable punishment is deprivation of liberty for a period up to eight years.

Section 294(2). Compelling of Testimony

For the compelling of testimony at an interrogation, if such is related to torture and if it has been committed by an official who performs pre-trial criminal proceedings, the applicable punishment is the deprivation of liberty for a period of up to ten years.

Section 301(3). Compelling the Giving of False Testimony, Explanations, Opinions and Translations

For a person who illegally influences, if such acts are related to torture, a witness, victim, person against whom the criminal proceedings have been commenced, detained, suspect, accused, applicant, expert or translator, for the purpose of compelling him or her to give false testimony or to certify on oath a false explanation to a court in an administrative matter, or a false opinion, or to provide a false translation, or to refrain from giving testimony or an opinion, or providing a translation, the applicable punishment is the deprivation of liberty for a period of up to ten years.

Section 317(3). Exceeding Official Authority

For a person who, being a public official, commits intentional acts which manifestly exceed the limits of rights and authority granted to the public official by law or according to his or her assigned duties, if substantial harm has been caused thereby to State authority, administrative order or interests protected by law of a person, and if such acts are related to torture, the applicable punishment is the deprivation of liberty for a period of up to ten years, with the deprivation of the right to take up a specific office for a period of up to five years.

Interestingly, some of the Latvian legal provisions are seemingly similar to the Russian Criminal Code’s reference to acts causing intentional bodily harm and having “the nature of ill-treatment or torture.” Another feature of the Latvian system is that while defining different types of ill-treatment as separate crimes, including those not causing serious physical harm (and involving lighter punishment), Latvian legislation does not provide a definition of ‘torture’ (just like European human rights law, as discussed above).

At the same time, the Latvian Criminal Code contains three articles addressing various types of unlawful pressure combined with torture in a number of situations, e.g. in regard to witnesses, victims and suspects. In addition to this, there is a separate crime of exceeding official powers, of which one component is the use of torture by a public official. Punishment for the said crimes is substantially tougher than for ‘ordinary’ torture and may be up to ten years of prison.

Thus, Latvian law offers a wide range of options for use by law enforcers to make sure that no type of torture-like abuse goes unpunished, with progressively tougher sanctions if the abuser is a public official rather than a private person. Notably, in the case of a public official, an essential test for finding them guilty is the use of torture per se irrespective of the extent of injury to the victim.

Does this mean that the right choice of legal regulation is enough to deal effectively with the problem of torture by minimising if not eliminating it from the life of today’s societies? This would be a very naive and ill-founded conclusion. But finding an appropriate legal solution is essential for placing torture outside the mainstream day-to-day practices of law enforcement agencies. Still, many unresolved issues remain.

Among them is what the above-mentioned expert defined as the ‘horizontal’ use of torture by public officials who know or are supposed to know about the imminent threat of torture by third parties but fail to warn them against it. Such situations are common in circumstances where victims are placed in custody of the State, such as prisons, psychiatric institutions, and others. What criteria should be used in these cases to determine whether or not the officials in charge have responded adequately, and under what circumstances may such officials be exempt from criminal prosecution or at least face lighter punishments? Perhaps the same is true in an even broader range of cases involving the use of violence without danger to life or health or without intent to cause harm to the victim. While we have seen this aspect addressed in European law and in domestic legislation of EU member states (e.g. Latvia), laws and especially practices of other countries do not normally warrant criminal prosecution for causing this type of suffering in this type of situation, particularly against public officials in countries such as Russia which do not make their agents legally liable for acts perceived as ‘harmless’.

There are some other pertinent circumstances to be considered.

For example, sometimes it is not so much the treatment itself that is cruel, inhuman or degrading but the fact that a punishment, while formally legal, is not appropriate given the circumstances or the person involved. Another example is detention in clearly inadequate conditions amounting to torture, if only by virtue of its duration or the degree of isolation from other people. This brings us to the concept of ‘psychological torture’, which is increasingly explored by lawyers and related professions. (Recently, a monograph on the topic was published in Russia, but so far the topic has not been adequately defined or addressed in criminal law).

In another type of situation, it can be difficult to draw a line between different forms of ill-treatment: while each of them separately may not lead to ‘torture-like’ suffering, these forms of treatment or detention conditions can amount to torture taken in sum.

Yet another issue arises in circumstances where the victim feels humiliated but their suffering does not reach a level where it can be defined as ‘amounting to torture’, let alone causing physical pain or mental disturbances. Such situations do not easily lend themselves to legal differentiation and thus to regulation. Indeed, it is not accidental that Latvian criminal law has a separate provision for acts causing suffering but different from torture. This implies that certain intentional acts may cause pain and suffering which are less severe than torture but still merit impartial investigation and possible punishment.

Commentary to judicial and investigative practices in such cases usually highlights the importance of examining the purpose behind the public official’s actions—whether there was none or whether the purpose was to place the victim in conditions known to be worse than their current status, which can be qualified as ill-treatment. Another important aspect is intent: whether it was the official’s intent to cause pain, suffering or humiliation, or whether certain external circumstances, including the victim’s personal characteristics unknown to the law enforcement agent, produced the adverse effect.

As we can see, our discussion of the issue leaves more questions than answers. Perhaps one of the purposes of the roundtable was to initiate further debate on these topics, preferably with reference to their treatment under various European jurisdictions and to relevant social practices, which could be reviewed and shared here in Legal Dialogue.[:]

| ↑ 1 | Latvia’s Criminal Code |

|---|

Section 125(2)(4). Intentional Serious Bodily Injury

For a person who commits intentional infliction of such bodily injury as is dangerous to life or has been the cause of loss of vision, hearing or any other organs or functions of organs, or mental or other health disorder, if it is related to a general ongoing loss of ability to work to the extent of not less than one third, or has resulted in the termination of pregnancy, or has been manifested in irreparable facial disfigurement (serious bodily injury), if they have been in the nature of torment or torture, the applicable punishment is deprivation of liberty for a period of two and up to ten years, with or without probationary supervision for a period up to three years.

Section 126(2)(2). Intentional Moderate Bodily Injury

For a person who commits intentional infliction of such bodily injury as is not dangerous to life and has not resulted in the consequences provided for in Section 125 of this Law but has resulted in continued health disorder or general ongoing loss of ability to work to the extent of less than one third (moderate bodily injury), if they have been in the nature of torment or torture, the applicable punishment is the deprivation of liberty for a period of up to five years or temporary deprivation of liberty, or community service, or a fine, with or without probationary supervision for a period of up to three years.

Section 130(3)(2). Intentional Slight Bodily Injury

For a person who commits intentional infliction of slight bodily injury, if they have been in the nature of torment or torture, the applicable punishment is the deprivation of liberty for a period of up to three years or temporary deprivation of liberty, or community service, or a fine.

Section 130.1 Torture

For a person who commits torture, if such acts have not had the consequences provided for in Section 125, 126 or 130 of this Law, the applicable punishment is the deprivation of liberty for a period of up to one year or temporary deprivation of liberty, or community service, or a fine.

Section 272.1 (3). Compelling of False Explanations, Opinions or Translations at a Parliamentary Investigation Commission

For a person who commits illegal influencing for the purpose of achieving that a person shall give a false explanation, opinion or translation or refuses to give an explanation, opinion or translation to a parliamentary investigation commission, if they are related to torture, the applicable punishment is deprivation of liberty for a period up to eight years.

Section 294(2). Compelling of Testimony

For the compelling of testimony at an interrogation, if such is related to torture and if it has been committed by an official who performs pre-trial criminal proceedings, the applicable punishment is the deprivation of liberty for a period of up to ten years.

Section 301(3). Compelling the Giving of False Testimony, Explanations, Opinions and Translations

For a person who illegally influences, if such acts are related to torture, a witness, victim, person against whom the criminal proceedings have been commenced, detained, suspect, accused, applicant, expert or translator, for the purpose of compelling him or her to give false testimony or to certify on oath a false explanation to a court in an administrative matter, or a false opinion, or to provide a false translation, or to refrain from giving testimony or an opinion, or providing a translation, the applicable punishment is the deprivation of liberty for a period of up to ten years.

Section 317(3). Exceeding Official Authority

For a person who, being a public official, commits intentional acts which manifestly exceed the limits of rights and authority granted to the public official by law or according to his or her assigned duties, if substantial harm has been caused thereby to State authority, administrative order or interests protected by law of a person, and if such acts are related to torture, the applicable punishment is the deprivation of liberty for a period of up to ten years, with the deprivation of the right to take up a specific office for a period of up to five years.

Conditional Sentences (Условные предложения).

В английском языке имеется 3 типа условных предложений.

1. В условных предложениях 1 типа сказуемое обозначает реальное действие или реальный факт действительности.

Главное предложение Придаточное предложение

Simple Future Simple Present

I shall tell this story. If I see an attorney to night

Я расскажу эту историю. Если увижу сегодня адвоката.

2. В условных предложениях 2 типа сказуемое выражает предполагаемое или желаемое действие, которое может относиться либо к настоящему, либо к будущему времени.

Главное предложение Придаточное предложение

Would (should) +infinitive (без to) формы, совпадающие с Simple

Past и Past Continuous

I should tell the real story. Я бы рассказал правду If I saw an attorney to night. если бы я увидел адвоката сегодня

He would give evidence. Он бы дал показания If a lawyer asked him. eсли бы судья попросил его.

3. В условных предложениях 3 типа сказуемое обозначает предполагаемое или воображаемое действие, которое относится к прошлому. Это невыполнимое или невыполненное действие.

Главное предложение Придаточное предложение

Would (should)+perfect infinitive(без to) форма, совпадающая с Past

Perfect

She would have informed you. If I had asked her last night

Она бы проинформировала бы вас. eсли бы я попросил её вчера

The judge would have sentenced earlier If the lawyer had prepared all the papers last week

Судья вынес бы приговор раньше Если бы адвокат подготовил бы.

все документы на прошлой неделе.

4. Условные предложения могут также вводиться союзами if onlyесли бы (только), supposeесли бы, предложим, что (а что если бы); сочетание but forесли бы не может вводить условное выражение.

If only he had checked himself then. Если бы он только сдержался тогда.

Suppose he had missed the train.А что если бы он опоздал на поезд?

.But for you we would not be able to prove his innocence.Если бы не вы, мы бы не смогли доказать его невиновность.

But for his mother he wouldn’t have became a lawyer.Если бы не его мама, он не стал бы адвокатом.

Exercise 1. Read and translate.

1) I would certainly give you the number of the civil case if I had one.

2) What would you do if the policeman stopped and searched your vehicle.

3) If I only had reasonable grounds for suspecting him, I would tell him about it.

4) If you had informed us about his arrest, we would have immideately gone to police station.

5) If my son hadn’t made up his mind to become a lawyer, I would have tried to persuade him.

6) If you had made an appointment with the lawyer last week; it would have been possible to settle the matter.

7) But for ALFA they could not be able to arrest the atrocious murder.

8) If he knew his rights to keep silent he would refuse to answer police questions.

10) Suppose she had recognized the criminal

POLICE AND PUBLIC

In 1829 Sir Richard Mayne, one of the founders of Scotland Yard, wrote: «The primary object of an efficient police is the prevention of crime and detection and punishment of offenders if crime is committed. To these ends all the efforts of police must be directed. The protection of life and property, the preservation of public tranquility, and the absence of crime, will alone prove whether those efforts have been successful and whether the objects for which the police were appointed have been attained.»

In attaining these objects, much depends on the approval and cooperation of the public, and these have always been determined by the degree of esteem and respect in which the police are held. Therefore, every member of the Force must remember that it is his duty to protect and help members of the public, no less than to bring offenders to justice. Consequently, while prompt to prevent crime and arrest criminals, he must look on himself as the servant and guardian of the general public and treat all law-abiding citizens, irrespective of their race, color, creed or social position, with unfailing patience and courtesy.

By the use of tact and good humor the public can normally be induced to comply with directions and thus the necessity for using force is avoided. If. however, persuasion, advice or warning is found to be ineffective, a resort to force may become necessary, as it is imperative that a police officer being required to take action shall act with the firmness necessary to render it effective.

TASK 1. Answer the following questions:

1. What are the objects of the police work according to Sir Richard Mayne?

2. How should the co-operation between the police and the public be achieved?

3. Why is the principle of police-public co-operation so important?

Police Discipline

The police are not above the law and must act within it. A police officer isan agent of the law of the land and maybe sued or prosecuted for any wrongful act committed in the performance of police duties. Officersare also subject to a disciplinary code designed to deal with abuse of police powers andmaintain public confidence in police impartiality. If found guilty of breaching the code, an officer canbe dismissed from the force.

Members of the public have the rightto make complaints against police officers if they feel that they have beentreated unfairly or improperly. In England and Wales theinvestigation and resolution of complaints is scrutinized by the independent Police Complaints Authority. The Authority must supervise any case involving death or serious injury and has discretion to supervise in any other case. In addition, the Authority reviews chief constables’ proposals on whetherdisciplinary charges should be brought against an officer who has beenthe subject of a complaint. If the chief constable doesnot recommend formal disciplinary charges, the Authority may, if it disagrees with the decision, recommend and, if necessary, direct that charges be brought.

The Government aims to ensure that the quality of service provided by police forces in Britaininspires public confidence, and that the police have the activesupport and involvement of the communities which they serve. The police service is taking effective action toimprove performance and standards. All forces in England and Wales have to consult with the communities they serve and develop policing policies to meet community demands. They have to be more open and explicit about their operations and the standards of service that they offer.

Virtually all forces haveliaison departments designed to develop closer contact between the force and the community. These departments consist of representatives from the police, local councilors and community groups.

Particular efforts are made to develop relations with young people through greater contact with schools and their pupils.

The Government has repeatedly stated itscommitment to improve relations between the police andethnic minorities. Central guidance recommends that all police officers should receivea thorough training in community and race relations issues. Home Office and police initiatives are designedto tackle racially motivated crime and to ensure that the issue is seen as a priority by thepolice. Discriminatory behavior by police officers, either to other officers or to members of the public, is an offence under the Police Discipline Code. All police forces recognize the need to recruit women and members of the ethnic minorities in orderto ensure that the police represent the community. Every force has an equal opportunities policy.

Task 3. Answer the following questions:

1. What disciplinary measures are police officers subject to?

2. What authorities supervise police conduct?

3. What helps improve police-public co-operation?

4. What is a liaison department?

5. How are race related issues tackled by the police?

Task 4 Complete the following text with the words and expressions given below:

misconduct; opinion polls; justice; sympathy; b violence; failures; complaints; terrorist offence; to confess

Most people have a positive attitude to the police, and ______ _______ have indicated that there is much public _____________ with men and women who have to deal with ________ _______. There is formal system through which __

_________________ of police behavior may be investigated, but in the late 1990s it was found that these procedures had not prevented some serious ________________ in the system of administering __________. Some Irish people had been convicted of a ___________ ____________ on the basis of confessions which had been improperly extracted from them, and the truth was discovered only after they had spent several year in prison. There were other cases too in which there were grounds for suspecting that the police had persuaded people _______ to crimes which they had not committed/ Some other inquiries revealed more cases of ________ by the police.

Task5 Fill in the gaps with the prepositions given below:

From; to; with; to; of

1. What is your attitude ____ the problem of crime prevention?

2. All the sympathies of the jury were ___ the defendant/

3. Finally the criminal was convicted ___ a violent assault/

4. The detective took pains to extract information ___ the eye-witness.

5. After a long questioning the suspect had to confess ___ committing a robbery.

Torture

Torture is the act of causing physical or mental anguish, pain, and/or harm, sometimes in order to achieve a specific result, such as obtaining information («enhanced interrogation» for the politically correct), or sometimes as revenge or to satisfy the sadistic nature of the torturer. During the Inquisition, torture was specifically and formally approved by Pope Innocent IV with his 1252 law, the papal bull Ad Extirpanda. [2]

In spite of a long history of the use of torture by governments, religions, and individuals, research has shown that information obtained by torture is notoriously unreliable, particularly for three reasons: [3] [4]

Contents

More problems [ edit ]

In addition to those three problems of not getting accurate information, torture hurts your overall policy effectiveness in several ways. This is more applicable for governments than for, say, bank robbers, but all the same:

Current events [ edit ]

Although outlawed by most countries, torture is still practiced by some, particularly dictatorships and other tyrannical or authoritarian governments. The United States has a prohibition against it, but this was all-too-frequently circumvented by outsourcing the dirty work to private contractors, ensuring that no one was actually tortured on U.S. soil, and, as a last resort, redefining the Geneva Conventions to suit. [16] Ain’t obeying the law grand, Republicans? There is increasing evidence that the US, in many cases, directly engaged in torture. They just made sure to do it in gray areas, like Guantanamo. [17] [18] [19]

Effectiveness [ edit ]

The military (and, formerly, the CIA) claimed that torture is a worthless tactic, as the victim will admit anything to stop the torture. For gathering useful intelligence, gaining trust, bribery, or undercover operations are far more useful tactics and don’t result in the physical or mental destruction of anyone.

Terrorist propaganda tool [ edit ]

With regard to terrorism, also, torture can also serve as a catalyst to increase terrorist activity. A terrorist organization needs to play to prejudices or other discontent on the part of its potential recruits; beating, arresting, and especially torturing or killing people gives terrorists propaganda fuel. [20] Treating them like human beings and entering into legitimate, fair political negotiation (even when abstaining from appeasing them) does not.

Most recently, the 2014 Senate report detailing how the US tortured prisoners during the War on Terror was a propaganda goldmine for overseas terrorist groups like Al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and DAESH. [21] The FBI and the Department of Homeland Security released a joint statement saying: «The FBI, DHS, and [National Counterterrorism Center] assess the most likely impact of the report will be attempts by foreign terrorist organizations … and their online supporters to exploit the report’s findings by claiming they confirm the U.S. government’s perceived hypocrisy and oppression of Muslims.» [21] The international intelligence community has also noted that DAESH dresses its Western beheading victims in orange jumpsuits to deliberately evoke similarities to prisoners of Guantanamo Bay. [21]

Tick, tick, bullshit [ edit ]

Those who advocate the use of torture frequently invoke the «ticking bomb» scenario: the need to extract from someone the location of a bomb, usually specified as nuclear, set to go off at an unknown (to the torturers) location at some time in the immediate future. [22] This is stupid because such a scenario has never happened, will never happen, and torture will be used regardless of whether there is a «ticking bomb» or not. [23] [24]

Besides, even if this kind of situation did occur, the person being tortured knows that he is in the position of power and needs only to resist for a finite period of time. In this situation, resistance to torture becomes easier, and delaying tactics such as feigning confusion (if it’s necessary to feign it), easily produced disinformation, or prolonged silence will achieve the aim of running out the clock. It isn’t hard to figure this out. It’s already been observed that torture tends to piss the victim off and make them more fanatical and more determined to either resist or mislead their torturers. [25] Your enemy’s enemy might be your friend, but your torturer certainly isn’t.

Guantanamo [ edit ]

It has been admitted the US military engaged in torture, including waterboarding, at the US Navy base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba (in fact, many of the methods later used at Abu Ghraib apparently came from Guantanamo). [26] ) The detention facility (Camp Delta, formerly Camp X-Ray) is an interesting study into the follies of America’s current policies regarding detainees. Despite the inhumane treatment of detainees, clear violations of the Geneva Convention (and the Vienna Convention on Treaties, which allows the camp to exist in the first place), Camp Delta and X-Ray have gathered little workable intelligence. While some high-ranking al-Qaeda members have been captured or killed, the organization (which is, in reality, more a philosophy than an actual organization) still remains active worldwide. The insurgency in Afghanistan is as strong as ever, and al-Qaeda retains significant influence throughout the Middle East and Africa. Camp Delta is still operational to this day, despite Barack Obama’s promise to close it.

Karl Rove, also known as «Bush’s brain,» said he «was proud we used techniques that broke the will of these terrorists.» [27] Exactly what Imperial Japan said.

Extraordinary rendition [ edit ]

Extraordinary rendition is when the United States, determined to break someone without dirtying its own hands, sends a suspect to a state that engages in the worst kind of torture. For example, despite all the heated rhetoric the US promulgates about Syria, some of the people the US has captured have been sent there to be tortured.

Ashcroft-Gonzales hospital incident [ edit ]

When then-Attorney General John Ashcroft was in the hospital (and under sedation), his deputy found that many of the programs of the Bush administration (possibly including torture) were illegal. Alberto Gonzales, then White House Counsel, went to visit Ashcroft in the hospital to try to get him to sign off on the programs. Ashcroft refused, rightfully understanding that he was in no position to sign off on anything, and told Gonzalez to talk to his deputy, who was currently the acting Attorney General. Then, after getting out of the hospital, Ashcroft signed off anyway. [28]

World public rejects torture, mostly [ edit ]

A June 2008 international survey of public attitudes to torture is rather depressing for the reality-based community: only 53% think that «All torture should be prohibited.» This contrasts with the UK where the figure is 82%. Oddly enough, most of the current techniques used by Americans were developed by the British. [29]

The US falls below states like Ukraine, Poland, and Egypt and 13% think «Torture should generally be allowed.» [30]

History [ edit ]

An historical aside: In ancient Greece and Rome, and possibly elsewhere, the testimony of a slave could only be accepted by an official tribunal or court after the slave had been tortured. Surprisingly, Greece and Rome were considered at the time to be civilized countries. Of course, pretty much all and every society throughout history has considered itself to be the most advanced civilization ever.

Psychiatric and case-study methods

Bentham approach

Neoclassical school

Preventive approach

TREATMENT OF CRIMINALS

(2) The Bentham approach was in part superseded in the late 19 th and early 20 th centuries by a movement known as the neoclassical school. This school, rejecting fixed punishments, proposed that sentences vary with the particular circumstances of a crime, such as the age, intellectual level, and emotional state of the offender; the motives and other conditions that may have incited to crime; and the offender’s past record and chances of rehabilitation. The influence of the neoclassical school led to the development of such concepts as grades of crime and punishment, indeterminate sentences, and the limited responsibility of young or mentally deficient offenders.

(3) At about the same time, the so-called Italian school stressed measures for preventing crime rather than punishing it. Members of this school argued that individuals are shaped by forces beyond their control and therefore cannot be held fully responsible for their crimes.They urged birth control, censorship of pornographic literature, and other actions designed to mitigate the influences contributing to crime. The Italian school has had a lasting influence on the thinking of present-day criminologists.

(4) The modern approach to the treatment of criminals owes most to psychiatric and case-study methods. Much continues to be learned from offenders who have been placed on probation or parole and whose behavior, both in and out of prison, has been studied intensively. The contemporary scientific attitude is that criminals are individual personalities and that their rehabilitation can be brought about only through individual treatment.Increased juvenile crime has aroused public concern and has stimulated study of the emotional disturbances that foster delinquency. This growing understanding of delinquency has contributed to the understanding of criminals of all ages.

(5) During recent years, crime has been under attack from many directions. The treatment and rehabilitation of criminals has improved in many areas. The emotional problems of convicts have been studied and efforts have been made to help such offenders. Much, however, remains to be done. Parole boards have engaged persons trained in psychology and social work to help convicts on parole or probation adjust to society.Various states have agencies with programs of reform and rehabilitation for both adult and juvenile offenders.

Many communities have initiated concerted attacks on the conditions that breed crime. Criminologists recognize that both adult and juvenile crime stem chiefly from the breakdown of traditional social norms and controls, resulting from industrialization, urbanization, increasing physical and social mobility, and the effects of economic crises and wars.Most criminologists believe that effective crime prevention requires community agencies and programs to provide the guidance and control performed, ideally and traditionally, by the family and by the force of social custom. Although the crime rate has not drastically diminished as a result of these efforts, it is hoped that the extension and improvement of all valid approaches to prevention of crime eventually will reduce its incidence.

Exercise 2: Write down the translation of the sentences from the text above given in bold type.

Exercise 3: Find in the text the English equivalents for the following words and expressions:

Exercise 4: Give Russian equivalents for the following general types of punishment. Put them in descending order of severity.

• Disciplinary training in a detention centre

• Fixed penalty fine

Exercise 5: Study the following list of offences. Rate them on a scale from 1 to 10 (1 is a minor offence, 10 is a very serious crime). They are in no particular order. You don’t have to apply your knowledge of existing laws — your own opinion is necessary:

□ driving in excess of the speed limit

□ common assault (e.g. a fight in a disco-club)

□ drinking and driving

□ malicious wounding (e.g. stabbing someone in a fight)

□ murdering a policeman during a robbery

□ murdering a child

□ causing death by dangerous driving

□ selling drugs (such as heroin)

□ stealing £1,000 from a bank by fraud

□ stealing £1,000 worth of goods from someone’s home

□ grievous bodily harm (almost killing someone)

□ stealing £1,000 from a bank by threatening someone with a gun

□ possession of a gun without a licence

Text 2:Translate the following texts:

Manslaughter

In 1981 Marianne Bachmeir, from Lubeck, West Germany, was in court watching the trial of Klaus Grabowski, who had murdered her 7 year-old daughter. Grabowski had a history of attacking children. During the trial, Frau Bachmeir pulled a Beretta 22 pistol from her handbag and fired eight bullets, six of which hit Grabowski, killing him. The defence said she had bought the pistol with the intention of committing suicide, but when she saw Grabowski in court she drew the pistol and pulled the trigger. She was found not guilty of murder, but was given six years imprisonment for manslaughter. West German newspapers reflected the opinion of millions of Germans that she should have been freed, calling her ‘the avenging mother’.

Crime of Passion

Bernard Lewis, a thirty-six-old man, while preparing dinner became involved in an argument with his drunken wife. In a fit of a rage Lewis, using the kitchen knife with which he had been preparing the meal, stabbed and killed his wife. He immediately called for assistance, and readily confessed when the first patrolman appeared on the scene with the ambulance attendant. He pleaded guilty to manslaughter. The probation department’s investigation indicated that Lewis was a rigid individual who never drank, worked regularly, and had no previous criminal record. His thirty-year-old deceased wife, and mother of three children, was a ‘fine girl’ when sober but was frequently drunk and on a number of occasions when intoxicated had left their small children unattended. After due consideration of the background of the offence and especially of the plight of the three motherless youngsters, the judge placed Lewis on probation so that he could work, support and take care of the children. On probation Lewis adjusted well, worked regularly, appeared to be devoted to the children, and a few years later was discharged as ‘improved’ from probation.

Murder

In 1952 two youths in Mitcham, London, decided to rob a dairy. They were Christopher Craig, aged 16, and Derek William Bentley, 19. During the robbery they were disturbed by Sydney Miles, a policeman. Craig produced a gun and killed the policeman. At that time Britain still had the death penalty for certain types of murder, including murder during a robbery. Because Craig was under 18, he was sentenced to life imprisonment. Bently who had never touched the gun, was over 18. He was hanged in 1953. The case was quoted by opponents of capital punishment, which was abolished in 1965.

Assault

In 1976 a drunk walked into a supermarket. When the manager asked him to leave, the drunk assaulted him, knocking out a tooth. A policeman who arrived and tried to stop the fight had his jaw broken. The drunk was fined 10 pounds.

Shop-lifting

In June 1980 Lady Isabel Barnett, a well-known TV personality was convicted of stealing a tin of tuna fish and a carton of cream, total value 87p, from a small shop. The case was given enormous publicity. She was fined 75 pounds and had to pay 200 pounds towards the cost of the case. A few days later she killed herself.

Fraud

This is an example of a civil case rather than a criminal one, A man had taken out an insurance policy of 100,000 pounds on his life. The policy was due to expire at 3 o’clock on a certain day. The man was in serious financial difficulties, and at 2.30 on the expire day he consulted his solicitor. He then went out and called a taxi. He asked the driver to make a note of the time, 2.50. He then shot himself. Suicide used not to cancel an insurance policy automatically. (It does nowadays.) The company refused to pay the man’s wife, and the courts supported them.

UNIT 15. CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

Text 1: Match the following headings with the sections of the text below:

• Effectiveness

• History

• Moral aspect

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT: HISTORY

(1) Capital punishment is a legal infliction of the death penalty, in modern law, corporal punishment in its most severe form. The usual alternative to the death penalty is long-term or life imprisonment.

The earliest historical records contain evidence of capital punishment. It was mentioned in the Code of Hammurabi. The Bible prescribed death as the penalty for more than 30 different crimes, ranging from murder to fornication. The Draconian Code of ancient Greece imposed capital punishment for every offence.

In England, during the reign of William the Conqueror, the death penalty was not used, although the results of interrogation and torture were often fatal. By the end of the 15 th century, English law recognized six major crimes: treason, murder, larceny; burglary, rape, and arson. By 1800, more than 200 capital crimes were recognized, and as a result, 1000 or more persons were sentenced to death each year (although most sentences were commuted by royal pardon). In early American colonies the death penalty was commonly authorized for a wide variety of crimes. Blacks, whether slave or free, were threatened with death for many crimes that were punished less severely when committed by whites.

Efforts to abolish the death penalty did not gather momentum until the end of the 18 th century. In Europe, a short treatise, On Crimes and Punishments, by the Italian jurist Cesare Beccaria, inspired influential thinkers such as the French philosopher Voltaire to oppose torture, flogging, and the death penalty.

The abolition of capital punishment in England in November 1965 was welcomed by most people with humane and progressive ideas. To them it seemed a departure from feudalism, from the cruel pre-Christian spirit of revenge: an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth. Many of these people think differently now. Since the abolition of capital punishment crime — and especially murder — has been on increase throughout Britain. Today, therefore, public opinion in Britain has changed. People who before, also in Parliament, stated that capital punishment was not a deterrent to murder — for there have always been murders in all countries with or without the law of execution — now feel that killing the assassin is the lesser of two evils. Capital punishment, they think, may not be the ideal answer, but it is better than nothing, especially when, as in England, a sentence of life imprisonment only lasts eight or nine years.

(2)The fundamental questions raised by the death penalty are whether it is an effective deterrent to violent crime, and whether it is more effective than the alternative of long-term imprisonment.

DEFENDERS of the death penalty insist that because taking an offender’s life is a more severe punishment than any prison term, it must be the better deterrent. SUPPORTERS also argue that no adequate deterrent in life imprisonment is effective for those already serving a life term who commit murder while being in prison, and for revolutionaries, terrorists, traitors, and spies.

In the U.S. those who argue against the death penalty as a deterrent to crime cite the following: (1) Adjacent states, in which one has a death penalty and the other does not, show no significant differences in the murder rate; (2) states that use the death penalty seem to have a higher number of homicides than states that do not use it; (3) states that abolish and then reintroduce the death penalty do not seem to show any significant change in the murder rate; (4) no change in the rate of homicides in a given city or state seems to occur following an expository execution.

In the early 1970s, some published reports showed that each execution in the U.S. deterred eight or more homicides, but subsequent research has discredited this finding. The current prevailing view among criminologists is that no conclusive evidence exists to show that the death penalty is a more effective deterrent to violent crime than long-term imprisonment.

(3)The classic moral arguments in favor of the death penalty have been biblical and call for retribution. «Whosoever sheds man’s blood, by man shall his blood be shed» has usually been interpreted as a divine warrant for putting the murderer to death. «Let the punishment fit the crime» is its secular counterpart; both statements imply that the murderer deserves to die. DEFENDERS of capital punishment have also claimed that society has the right to kill in defense of its members, just as the individual may kill in self-defense. The analogy to self-defense, however, is somewhat doubtful, as long as the effectiveness of the death penalty as a deterrent to violent crimes has not been proved.

The chief objection to capital punishment has been that it is always used unfairly, in at least three major ways. First, women are rarely sentenced to death and executed, even though 20 per cent of all homicides in recent years have been committed by women. Second, a disproportionate number of non-whites are sentenced to death and executed. Third, poor and friendless defendants, those with inexperienced or court-appointed attorney, are most likely to be sentenced to death and executed. DEFENDERS of the death penalty, however, have insisted that, because none of the laws of capital punishment causes sexist, racist, or class bias in its use, these kinds of discrimination are not a sufficient reason for abolishing the death penalty. OPPONENTS have replied that the death penalty can be the result of a mistake in practice and that it is impossible to administer fairly.

Exercise 1: Find in the text the English equivalents for the following words and expressions related to punishment:

Exercise 2: Translate the following passage into English paying special attention to the words in bold type:

На протяжении веков смертная казнь назначалась засамые разные виды преступлений. В середине века человека могли казнить за хищение имущества, изнасилованиеи даже поджог. Государственная измена была и остается во многих странах преступлением, наказуемым смертной казнью. Существует мнение, что даже долгосрочное или пожизненное тюремное заключение является бессмысленным наказанием для так называемых «идеологических» преступников: предателей, шпионов, террористов. Смертная казнь для такого рода преступников – меньшее из двух зол.

Exercise 3: Continue the table below with the following words and expressions describing polar views. The first few are done for you:

| FOR | AGAINST |

| proponent to argue in favour of amth. | opponent to argue against smth. |

● con ● to consent to smth.

● defender ● to contradict to smth.

● pro ● to accept smth.

● supporter ● to disagree with smth.

● to deny smth. ● to agree to/with smth.

● to admit smth. ● to oppose smth.

● to object to smth. ● to confirm smth.

Exercise 4: Translate the following famous statements:

| AGAINST | FOR |

| 1. “An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth!” – This is a cruel pre-Christian spirit of revenge. We are civilized now – let’s give it up and be humane. | 1. “An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth!” – We should admit this Biblical principle. It’s eternal. |

| 2. “Let the punishment fit the crime”- We can not accept fixed punishments for crimes. Circumstances should be taken into account. | 2. “Let the punishment fit the crime”- Those who steal should be deprived of their property, those who kill should be deprived of their own lives! |

| 3. “It is much more prudent to acquit two persons, though actually guilty, than to pass a sentence oа condemnation on one that is virtuous and innocent.” (Voltaire) | 3. “The pain of the penalty should outweigh only slightly the pleasure of success in crime.” (J. Bentham) |

| 4. “An evil deed is not redeemed by an evil deed of retaliation.” (C.S. King) | 4. “The primary purpose of the punishment which society inflicts is to redress the disorder caused by the offence.” (Pope John Paul II) |

| 5. “Whosoever sheds man’s blood, by man shall his blood be shed.” (The Bible) |

Text 2: CAPITAL PUNISHMENT: FOR AND AGAINST

Perhaps all criminals should be required to carry cards which read: «Fragile: Handle With Care». It will never do, these days, to go around referring to criminals as violent thugs. You must refer to them politely as ‘social misfits’. The professional killer who wouldn’t think twice about using his cosh or crowbar to batter some harmless old lady to death in order to rob her of her meagre life-savings must never be given a dose of his own medicine. He is in need of ‘hospital treatment’. According to his misguided defenders, society is to blame. A wicked society breeds evil — or so the argument goes. When you listen to this kind of talk, it makes you wonder why we aren’t all criminals. We have done away with the absurdly harsh laws of the nineteenth century and this is only right. But surely enough is enough. The most senseless piece of criminal legislation in Britain and a number of other countries has been the suspension of capital punishment.

The violent criminal has become a kind of hero-figure in our time. He is glorified on the screen; he is pursued by the press and paid vast sums of money for his ‘memoirs’. Newspapers which specialize in crime-reporting enjoy enormous circulations and the publishers of trashy cops and robbers stories or ‘murder mysteries’ have never had it so good. When you read about the achievements of the great train robbers, it makes you wonder whether you are reading about some glorious resistance movement. The hardened criminal is cuddled and cosseted by the sociologists on the one hand and adored as a hero by the masses on the other. It’s no wonder he is a privileged person who expects and receives VIP treatment wherever he goes.

Exercise 5: Explain the meaning of the following words and expressions:

• a cold-blooded poisoner • to breed evil

• a desperate villain • to cosset

• a hardened criminal • to cuddle

• a professional killer • to deter criminals

• a social misfit • to do away with

• a train robber • to get away with murder

• a violent criminal • to go on committing offences

• a violent robber • to mow down

• a violent thug • to think twice

• to pull the trigger

Exercise 6: Read the text below and translate it paying special attention to the words and expressions in bold type.

Пришло время отменить смертную казнь. С каждым годом это становится все более очевидным. Опыт всех стран показывает, что смертная казнь приводит к ожесточению в обществе. В ряде стран смертные приговоры применяются в основном к представителям неимущих слоев населениялибо расовыхили этнических меньшинств.

Оправдывая смертную казнь, чаще всего говорят, что она необходима, по крайней мере временно, для блага общества.

Однако имеет ли государство право лишать человека жизни?

Смертная казнь – это предумышленное и хладнокровное убийство человека государством. Само существование этой меры наказания является попранием основных прав человека: международное право запрещает жестокие, негуманные или унижающие человека наказания.

Многовековой опыт применения высшей меры наказания и научные исследования о взаимосвязи смертной казни и уровня преступности не дали убедительных доказательств, что смертная казнь способна эффективно защитить общество от преступности или способствовать правосудию. Ни одна система уголовной юстиции не доказала свою способность последовательно и справедливо решать, кто должен жить и кто – умереть. Некоторым удается избежать смертной казни с помощью квалифицированных защитников; другим – потому что их судят мягкосердечные судьи или присяжные; третьим помогают их политически связи или положение в обществе.

Существует определенный процент судебных ошибок, последствия которых особенно трагичны при приведении смертного приговора в исполнение.

Text 3: Translate the following facts and arguments:

Financial Costs

The death penalty is not now, nor has it ever been, a more economical alternative to life imprisonment. A murder trial normally takes much longer when the death penalty is at issue than when it is not. Litigation costs — including the time of judges, prosecutors, public defenders, and court reporters, and the high costs of briefs — are all borne by the taxpayer.

Inevitability of Error

In 1975, only a year before the Supreme Court affirmed the constitutionality of capital punishment, two African-American men in Florida were released from prison after twelve years awaiting execution for the murder of two white men. Their convictions were the result of coerced confessions, erroneous testimony of an alleged eyewitness, and incompetent defense counsel. Though a white man eventually admitted his guilt, a nine-year legal battle was required before the governor would grant them a pardon. Had their execution not been stayed while the constitutional status of the death penalty was argued in the courts, these two innocent men probably would not be alive today.

Barbarity

Deterrence

Gangland killings, air piracy, drive-by shootings, and kidnapping for ransom are among the graver felonies that continue to be committed because some individuals think they are too clever to get caught. Political terrorism is usually committed in the name of an ideology that honors its martyrs; trying to cope with it by threatening terrorists with death penalty is futile.

Exercise 7: “Pros” and “Cons” for capital punishment

| Cons (against) | Pros (for) |

| It’s useless.Statistics demonstrates that its retention or suppression has no effect on the number of crimes committed. Furthermore, the death of the offender neither benefits anyone nor restores anything. For example, if a 40-year-old man, who has no family, no money and no home kills a 20-year-old student who has parents, who is young, happy and has all his life ahead, would the capital punishment be fair or would it compensate anything? | The murderer is a threat to society and society must protect itself |

| It’s immoral. The criminal may be a pervert, mentally sick or be not adequate in some other ways. Furthermore there’s always the possibility of an error of judgment which is totally uncorrectable. | The death of one offender should be the frightening example for another one. |

| It’s unnecessary.For the defense of society it is enough to shut the offender away. | That very offender who was sentenced will never escape or repeat his offence again. Furthermore, the murderer is able to manipulate other people from inside the prison and make them commit murders or other offences. |

| It’s pessimistic.Death penalty means that we deny all the possibilities of redemption that we refuse to admit that we may change or improve. | Society has the right to kill in defense of its members, just as individual may kill in self-defense. |

| It’s unjust. A competitive and consumer society makes its weak members scapegoats for sins which belong largely to society as a whole. | Because taking an offenders life is a more severe punishment than any prison term, it must be the better deterrent. |

| It’s antichristian. The general orientation of the Bible is clearly in favour of life, forgiveness and hope. And it is to be applied not only to the conduct of the individual but also to the whole society. Revenge and murder are not Christian notions. | No adequate deterrent in life imprisonment is effective for those already serving a life term who commit murder while being in prison, and for revolutionaries, terrorists, traitors, and spies. |

| We shouldn’t be blinded over emotional arguments: glorification of criminal on screen, etc., irrelevant. | |

| Those in favour of capital punishment are motivated only by desire for revenge and retaliation. | |

| Hanging, electric chairs, garroting, etc., are barbaric practices, unworthy of human beings. | |

| Capital punishment creates, it does not solve, problems. Solution lies elsewhere: society is to blame. Overcrowding, slums, poverty, broken homes: these are the factors that lead to crime. Crime can only be drastically reduced by the elimination of social injustices – not by creating so-called “deterrents” when the real problems remain unsolved. |

Text 4: ABOLITION OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

The quantity of countries which submit a plan for abolishing the capital punishment increases quickly. At the end of 1995 capital punishment was abolished in 72 countries (among which are Greece, Italy, the USA, Romania, Hungary, Russia, Spain, the South African Republic) and in 90 countries it is still preserved. At the same time the evolution in this direction is not occurring everywhere. In some countries we can see the opposite tendencies: either to restore capital punishment (as in 2 states of the USA) or to enlarge the sphere it is applied to (Korea, China, Nigeria and some Arabian countries). While examining the question concerning capital punishment, the journalists made inquires and cited statistics (80% are for the implementation of capital punishment, and 12% are for life imprisonment).

The following analysis enables us to differentiate the attitude towards capital punishment among the different social groups. As it turned out the men are more likely to be the defenders of capital punishment, but at the same time 77% of women are usual victims. There are not so many supporters of capital punishment among coloured people (2 times as little as among whites). With the increase of age the quantity of the voters against capital punishment visibly decreases while the great quantity of its supporters is youth. The explanation of such a conformity depends upon the fact that 25% of all the victims are young people at the age of 18-24. The inhabitants of rural districts and suburbs vote for capital punishment.

The most interesting is the statistics which reflects the connection between the attitude to the capital punishment and religious convictions. Among the supporters of capital punishment there are 27% of Christians and 10% of the representatives of Moslems.

The most important reason for the implementation of capital punishment is enormous expenditures on maintenance of the offenders in jails. The second one is insecurity of citizens, disbelief in the legal system.

The reasons against capital punishment are: there is always the fear of the jury error and also the psychologists made the research work and proved that neither the implementation nor the abolishment of capital punishment influence the dynamics of felonies.

There was another point for discussion – for whom the discounts should be made. The world community decided to abate pregnant women, mentally deficient people, juveniles, elderly people. They voted for the change of capital punishment into life imprisonment. In accordance with our legislation capital punishment is not implemented to pregnant women as the lawyers make a discount to their emotional and physical state, but statistics shows that they commit crimes driven to the despair by their husbands for the sake of children. As far as juveniles are concerned, some countries increased the age of implementation up to 20 or 22, but again statistics shows that the most brutal, cruel crimes are committed in adolescence. Every case concerning juveniles is supposed to be examined individually. But here the jury must take into account the juveniles’ emotional state, they just act according to emotions, outbursts while committing crimes.

Тексты для дополнительного чтения и перевода

Содержание:

TEXT 1: A GLIMPSE OF BRITISH POLITICAL HISTORY………………………..141

TEXT 2: THE ENGLISH POLITICAL HERITAGE………………………………….142

TEXT 3: THE IDEAS OF JOHN LOCKE…………………………………………….142

TEXT 4: THE LEGAL HERITAGE OF FRANCE……………………………………143

TEXT 5: THE ROOTS OF AMERICAN GOVERNMENT…………………………. 143

TEXT 6: THE INDIAN SELF-GOVERNMENT IN NORTH AMERICA……………144

TEXT 7: GOVERNMENT IN THE COLONIES……………………………………. 145

TEXT 8: COLONIAL LEGISLATURES……………………………………………. 145

TEXT 9: COLONIAL SELF-GOVERNMENT………………………. 146

TEXT 11: ELEMENTS OF DEMOCRACY…………………………………………. 147

TEXT 12: CHARACTERISTICS OF DEMOCRACY………………………………. 147

TEXT 13: THE SOIL OF DEMOCRACY……………………………………………..148

TEXT 16: THE AMERICAN CIVIL SERVICE……………………………………….150

TEXT 17: THE ORIGINS OF THE CIVIL SERVICE SYSTEM……………………..150

TEXT 18: THE CONCEPT OF BICAMERAL LEGISLATURE……………………..151

TEXT 19: US CONGRESS RULES. ………………………………151

TEXT 20: LAWMAKING IN THE SENATE…………………………………………152

TEXT 21: CONGRESS AND THE PRESIDENT……………………………………..152

TEXT 22: VOTING IN THE USA……………………………………………………..153

TEXT 23: PARTIES AND PARTY SYSTEMS……………………………………….153

TEXT 24: RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES OF AMERICAN CITIZENS………154

TEXT 25: PROTECTING THE RIGHTS OF THE ACCUSED………………………154

TEXT 26: CRUEL AND UNUSUAL PUNISHMENT………………………………..155

TEXT 27: FREEDOM OF THE PRESS……………………………………………….156

TEXT 28: FREE PRESS AND FAIR TRIAL………………………………………….156

TEXT 29: FREEDOM OF SPEECH…………………………………………………. 157

TEXT 30: FREEDOM OF RELIGION………………………………………………. 157

TEXT 31: MASS MEDIA IN A DEMOCRATIC SOCIETY………………………….158

TEXT 32: THE PENTAGON PAPERS………………………………………………..158

TEXT 34: LEGAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS IN BRITAIN…..159

TEXT 35: CHARLES I AND THE CIVIL WAR……………………………………. 160

TEXT 36: THE ROYALISTS AND THE PARLIAMENTARIANS………………….161

TEXT 37: THE END OF THE CIVIL WAR…………………………………………..161

TEXT 38: THE HISTORY OF SPEAKERSHIP IN BRITAIN………………………..162

TEXT 39: THE SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS………. 162

TEXT 40: THE SPEAKER’S DUTIES…………………………………. 163

TEXT 41: DEBATE IN THE HOUSE OF COMMONS………………………………163

TEXT 42: UNPARLIAMENTARY LANGUAGE…………………………………….164

FAMOUS LEGAL DOCUMENTS THROUGHOUT HISTORY (EXTRACTS)

TEXT 1: Hammurabi’s Code of Laws (1758 B.C.)……………………………………..……. 130

TEXT 3: The Magna Carta (1215)………………………………………………………..……132

TEXT 4: The Petition of Rights (1628)………………………………………………..……….135

TEXT 5: The English Bill of Rights (1689)………………………………………..…………..137

TEXT 6: The U.S. Declaration of Independence (1776)……………………………………….141

TEXT 7: The U.S. Bill of Rights (1791)…………………………………..…………………. 142

TEXT 8: European Prison Rules (1990s)………………………………………………..……..143

PHILOSOPHERS OF LAW

TEXT 24: Butch Cassidy, 1866—1910 and the Sundance Kid, d. 1910………………. ……..154

TEXT 25: Mata Hari (born Gertruda Margarete Zelle), 1876—1917 …………………………154

TEXT 26: Captain Alfred Dreyfus, 1859—1935………………………………………………155

TEXT 27: Lizzie Borden, 1860—1927………………………………………………………. 155

TEXT 28: Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen, 1882—1910…………………………. 155

TEXT 29: Bonnie and Clyde (Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow), d. 1934………………..…..156

TEXT 31: Bruno Hauptmann, d. 1936……………………………………………..…………..156

TEXT 32: Hans Van Meegeren, 1889—1947…………………………………. 157

TEXT 33: Alphonse Capone, 1899—1947……………………………………. 157

TEXT 34: ‘Lucky Luciano’, 1897—1962………………………………………………………157

TEXT 35: Frank Costello, 1891—1973………………………………………………………..157

TEXT 36: George Blake, b. 1922………………………………………………………………158

TEXT 37: Lee Harvey Oswald, 1940—1963…………………………………………………..158

TEXT 42: Inspector Jules Maigret……………………………………………………………. 160

THE STUPIDEST CRIMINALS

TEXT 45: MuggersThieves……………………………………………………. 162

TEXT 47: Escape Artists………………………………………………………. 163

TEXT 51: ‘Miscellaneous’ Crooks……………………………………………………………. 165

PART I.

Механическое удерживание земляных масс: Механическое удерживание земляных масс на склоне обеспечивают контрфорсными сооружениями различных конструкций.

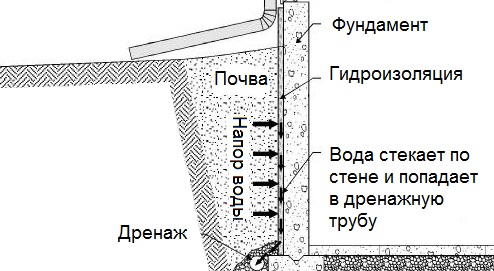

Общие условия выбора системы дренажа: Система дренажа выбирается в зависимости от характера защищаемого.

Организация стока поверхностных вод: Наибольшее количество влаги на земном шаре испаряется с поверхности морей и океанов (88‰).