What s so funny ielts reading answers

What s so funny ielts reading answers

What s so funny ielts reading answers

IELTS Reading-What’s so funny?

The joke comes over the headphones: ‘ Which side of a dog has the most hair? The left.’ No, not funny. Try again. ‘ Which side of a dog has the most hair? The outside.’ Hah! The punchline is silly yet fitting, tempting a smile, even a laugh. Laughter has always struck people as deeply mysterious, perhaps pointless. The writer Arthur Koestler dubbed it the luxury reflex: ‘unique in that it serves no apparent biological purpose’.

Theories about humour have an ancient pedigree. Plato expressed the idea that humour is simply a delighted feeling of superiority over others. Kant and Freud felt that joke-telling relies on building up a psychic tension which is safely punctured by the ludicrousness of the punchline. But most modern humour theorists have settled on some version of Aristotle’s belief that jokes are based on a reaction to or resolution of incongruity, when the punchline is either a nonsense or, though appearing silly, has a clever second meaning.

Graeme Ritchie, a computational linguist in Edinburgh, studies the linguistic structure of jokes in order to understand not only humour but language understanding and reasoning in machines. He says that while there is no single format for jokes, many revolve around a sudden and surprising conceptual shift. A comedian will present a situation followed by an unexpected interpretation that is also apt.

So even if a punchline sounds silly, the listener can see there is a clever semantic fit and that sudden mental ‘Aha!’ is the buzz that makes us laugh. Viewed from this angle, humour is just a form of creative insight, a sudden leap to a new perspective.

However, there is another type of laughter, the laughter of social appeasement and it is important to understand this too. Play is a crucial part of development in most young mammals. Rats produce ultrasonic squeaks to prevent their scuffles turning nasty. Chimpanzees have a ‘play-face’ – a gaping expression accompanied by a panting ‘ah, ah’ noise. In humans, these signals have mutated into smiles and laughs. Researchers believe social situations, rather than cognitive events such as jokes, trigger these instinctual markers of play or appeasement. People laugh on fairground rides or when tickled to flag a play situation, whether they feel amused or not.

Both social and cognitive types of laughter tap into the same expressive machinery in our brains, the emotion and motor circuits that produce smiles and excited vocalisations. However, if cognitive laughter is the product of more general thought processes, it should result from more expansive brain activity.

Psychologist Vinod Goel investigated humour using the new technique of ‘single event’ functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRl). An MRI scanner uses magnetic fields and radio waves to track the changes in oxygenated blood that accompany mental activity. Until recently, MRI scanners needed several minutes of activity and so could not be used to track rapid thought processes such as comprehending a joke. New developments now allow half-second ‘snapshots’ of all sorts of reasoning and problem-solving activities.

Making a rapid emotional assessment of the events of the moment is an extremely demanding job for the brain, animal or human. Energy and arousal levels may need, to be retuned in the blink of an eye. These abrupt changes will produce either positive or negative feelings. The orbital cortex, the region that becomes active in Goel’s experiment, seems the best candidate for the site that feeds such feelings into higher-level thought processes, with its close connections to the brain’s sub-cortical arousal apparatus and centres of metabolic control.

All warm-blooded animals make constant tiny adjustments in arousal in response to external events, but humans, who have developed a much more complicated internal life as a result of language, respond emotionally not only to their surroundings, but to their own thoughts. Whenever a sought-for answer snaps into place, there is a shudder of pleased recognition. Creative discovery being pleasurable, humans have learned to find ways of milking this natural response. The fact that jokes tap into our general evaluative machinery explains why the line between funny and disgusting, or funny and frightening, can be so fine. Whether a joke gives pleasure or pain depends on a person’s outlook.

Humour may be a luxury, but the mechanism behind it is no evolutionary accident. As Peter Derks, a psychologist at William and Mary College in Virginia, says: ‘I like to think of humour as the distorted mirror of the mind. It’s creative, perceptual, analytical and lingual. If we can figure out how the mind processes humour, then we’ll have a pretty good handle on how it works in general.

What’s so funny? IELTS Reading Passage with Answers

What’s so funny? IELTS Reading Passage

Reading Passage 2

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 14-20, which are based on the IELTSXpress Academic IELTS Reading Passage What’s so funny?

What’s so funny?

John McCrone reviews recent research on humour

The joke comes over the headphones: ‘Which side of a dog has the most hair? The left.’ No, not funny. Try again. ‘Which side of a dog has the most hair? The outside.’ Hah! The punchline is silly yet fitting, tempting a smile, even a laugh. Laughter has always struck people as deeply mysterious, perhaps pointless. The writer Arthur Koestler dubbed it the luxury reflex: ‘unique in that it serves no apparent biological purpose’.

Theories about humour have an ancient pedigree. Plato expressed the idea that humour is simply a delighted feeling of superiority over others. Kant and Freud felt that joke-telling relies on building up a psychic tension which is safely punctured by the ludicrousness of the punchline. But most modern humour theorists have settled on some version of Aristotle’s belief that jokes are based on a reaction to or resolution of incongruity, when the punchline is either nonsense or, though appearing silly, has a clever second meaning.

Graeme Ritchie, a computational linguist in Edinburgh, studies the linguistic structure of jokes in order to understand not only humour but language understanding and reasoning in machines. He says that while there is no single format for jokes, many revolve around a sudden and surprising conceptual shift. A comedian will present a situation followed by an unexpected interpretation that is also apt.

So even if a punchline sounds silly, the listener can see there is a clever semantic fit and that sudden mental ‘Aha!’ is the buzz that makes us laugh. Viewed from this angle, humour is just a form of creative insight, a sudden leap to a new perspective.

However, there is another type of laughter, the laughter of social appeasement and it is important to understand this too. Play is a crucial part of development in most young mammals. Rats produce ultrasonic squeaks to prevent their scuffles turning nasty. Chimpanzees have a ‘play-face’ – a gaping expression accompanied by a panting ‘ah, ah’ noise. In humans, these signals have mutated into smiles and laughs. Researchers believe social situations, rather than cognitive events such as jokes, trigger these instinctual markers of play or appeasement.

Both social and cognitive types of laughter tap into the same expressive machinery in our brains, the emotion and motor circuits that produce smiles and excited vocalisations. However, if cognitive laughter is the product of more general thought processes, it should result from more expansive brain activity.

Psychologist Vinod Goel investigated humour using the new technique of ‘single event’ functional magnetic resonance imaging (FMRI). An MRI scanner uses magnetic fields and radio waves to track the changes in oxygenated blood that accompany mental activity. Until recently, MRI scanners needed several minutes of activity and so could not be used to track rapid thought processes such as comprehending a joke. New developments now allow half-second ‘snapshots’ of all sorts of reasoning and problem-solving activities.

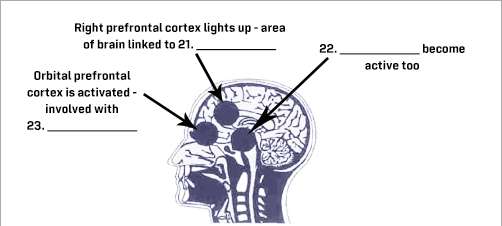

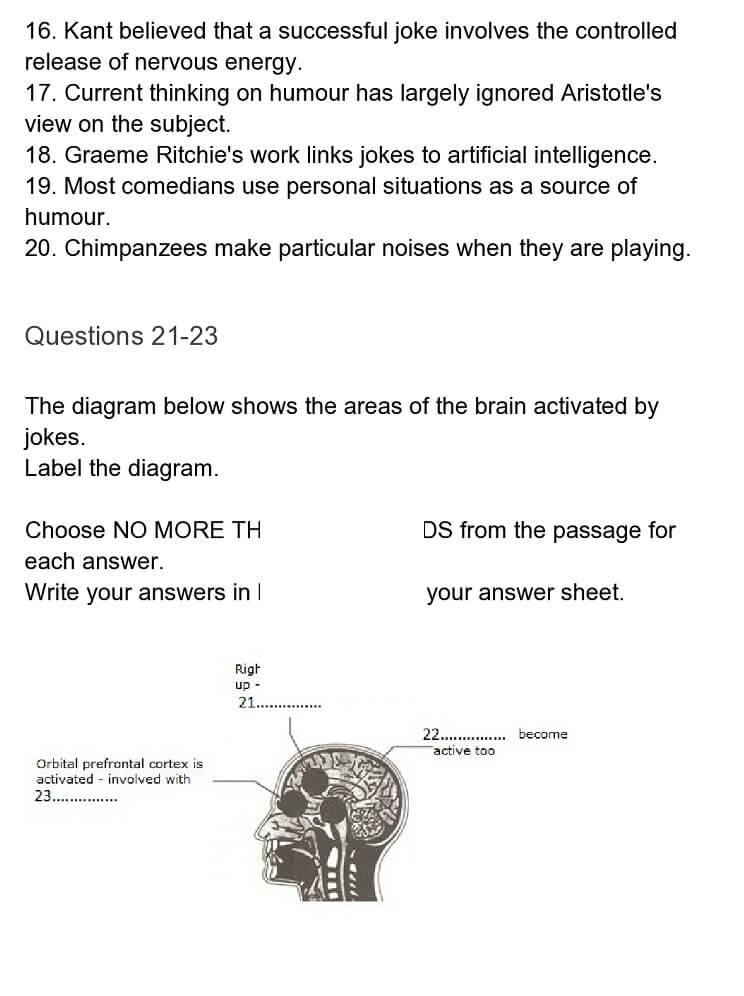

Although Goel felt being inside a brain scanner was hardly the ideal place for appreciating a joke, he found evidence that understanding a joke involves a widespread mental shift. His scans showed that at the beginning of a joke the listener’s prefrontal cortex lit up, particularly the right prefrontal believed to be critical for problem solving. But there was also activity in the temporal lobes at the side of the head (consistent with attempts to rouse stored knowledge) and in many other brain areas. Then when the punchline arrived, a new area sprang to life – the orbital prefrontal cortex. This patch of brain tucked behind the orbits of the eyes is associated with evaluating information.

Making a rapid emotional assessment of the events of the moment is an extremely demanding job for the brain, animal or human. Energy and arousal levels may need to be retuned in the blink of an eye. These abrupt changes will produce either positive or negative feelings. The orbital cortex, the region that becomes active in Goel’s experiment, seems the best candidate for the site that feeds such feelings into higher-level thought processes, with its close connections to the brain’s sub-cortical arousal apparatus and centres of metabolic control.

All warm-blooded animals make constant tiny adjustments in arousal in response to external events, but humans, who have developed a much more complicated internal life as a result of language, respond emotionally not only to their surroundings, but to their own thoughts. Whenever a sought-for answer snaps into place, there is a shudder of pleased recognition. Creative discovery being pleasurable, humans have learned to find ways of milking this natural response. The fact that jokes tap into our general evaluative machinery explains why the line between funny and disgusting, or funny and frightening, can be so fine. Whether a joke gives pleasure or pain depends on a person’s outlook.

Humour may be a luxury, but the mechanism behind it is no evolutionary accident. As Peter Derks, a psychologist at William and Mary College in Virginia, says: ‘I like to think of humour as the distorted mirror of the mind. It’s creative, perceptual, analytical and lingual. If we can figure out how the mind processes humour, then we’ll have a pretty good handle on how it works in general.

Questions 14-20

Do the following statements agree with the information given in IELTSXpress Reading Passage 2?

For questions 14-20, write

TRUE if the statement is True

FALSE if the statement is false

NOT GIVEN If the information is not given in the passage

14 Arthur Koestler considered laughter biologically important in several ways.

15 Plato believed humour to be a sign of above-average intelligence.

16 Kant believed that a successful joke involves the controlled release of nervous energy.

17 Current thinking on humour has largely ignored Aristotle’s view on the subject.

18 Graeme Ritchie’s work links jokes to artificial intelligence.

19 Most comedians use personal situations as a source of humour.

20 Chimpanzees make particular noises when they are playing.

Questions 21-23

The diagram below shows the areas of the brain activated by jokes.

Label the diagram.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Questions 24-27

Complete each sentence with the correct ending A-G below.

Write the correct letter A-G next to questions 24-27.

24 One of the brain’s most difficult tasks is to

25 Because of the language they have developed, humans

26 Individual responses to humour

27 Peter Derks believes that humour

A react to their own thoughts.

B helped create language in humans.

C respond instantly to whatever is happening.

D may provide valuable information about the operation of the brain.

E cope with difficult situations.

F relate to a person’s subjective views.

G led our ancestors to smile and then laugh.

What’s so Funny IELTS Reading Passage Answers

14. FALSE

15. NOT GIVEN

16. TRUE

17. FALSE

18. TRUE

19. NOT GIVEN

20. TRUE

21. problem solving

22. temporal lobes

23. evaluating information

24. C

25. A

26. F

27. D

What’s so Funny IELTS Reading Passage Answers Explanation

14. Arthur koestler considered laughter biologically important in several ways

Keywords: Arthur Koestler, biologically, important

Paragraph 1 states that “The writer Arthur Koestler dubbed it the luxury reflex: „unique in that it serves no apparent biological purpose”

Answer: FALSE

15. Plato believed humour to be a sign of above-average intelligence

Keywords: Plato,above-average, intelligence

In paragraph 2, the writer says that:” Plato expressed the idea that humour is simply a delighted feeling of superiority over others”. Thus, it is only a feeling of superiority, but the passage does not mention superiority in intelligence.

Answer: NOT GIVEN

16. Kant believed that a successful joke involves the controlled release of nervous energy

Keywords: Kant, release, nervous energy

In paragraph 2, we find: “Kant and Freud felt that joke-telling relies on building up apsychic tension which is safely punctured by the ludicrousness of the punchline”.

Answer: TRUE

17. Current thinking on humour has largely ignored aristotle”S view on the subject

Keywords: current, largely, ignored, Aristotle

At the end of paragraph 2, the writer says that: “But most modern humour theorists have settled on some version of Aristotle”s belief that jokes are based on a reaction to or resolution of incongruity, when the punchline is either a nonsense or, though appearing silly, has a clever second meaning.”

Answer: FALSE

18. Graeme ritchie”S work links jokes to artificial intelligence

Keywords: Graeme Ritchie, artificial, intelligence

In paragraph 3, the writer says that “Graeme Ritchie, a computational linguist in Edinburgh, studies the linguistic structure of jokes in order to understand not only humour but language understanding and reasoning in machines”, and “Viewed from this angle, humour is just a form of creative insight,a sudden leap to a new perspective”. Artificial intelligence: the intelligence of machines, computers which are created/programmed by humans.

Answer: TRUE

19. Most comedians use personal situations as a source of humour.

Keywords: comedians, personal situations, source of humour

In paragraph 3, the writer reports that:” He says that while there is no single format for jokes, many revolve around a sudden and surprising conceptual shift. A comedian will present a situation followed by an unexpected interpretation that is also apt”. This means there are a lot of different ways to tell a joke, for example, using a sudden, surprising/unexpected situation. He does not mention if comedians use personal situations to create humour.

Answer: NOT GIVEN

20. Chimpanzees make particular noises when they are playing.

Keywords: chimpanzees, noises, playing

Paragraph 5 indicates that: “Chimpanzees have a „play-face” – a gaping expression accompanied by a panting „ah,ah” noise. accompanied by: together with.

Answer: TRUE

21. Right prefrontal cortex lights up – area of brain linked to ……

Keywords: right prefrontal cortex, light up

In paragraph 8, the writer says that “His scans showed that at the beginning of a joke the listener’s prefrontal cortex lit up, particularly the right prefrontal believed to be critical for problem solving”

Answer: problem solving

22. ….Become active too

Keywords: active, too

In paragraph 8, the writer says that: “But there was also activity in the temporal lobes at the side of the head (consistent with attempts to rouse stored knowledge) and in many other brain areas.”

Answer: temporal lobes

23. Orbital prefrontal cortex is activated – involved with …

Keywords: orbital prefrontal cortex, activated, involved

Paragraph 8 says that: “Then when the punchline arrived, a new area sprang to life – the orbital prefrontal cortex. This patch of brain tucked behind the orbits of the eyes is associated with evaluating information”

Answer: evaluating information

24. One of the brain’s most difficult tasks is to…..

Keywords; brain, most difficult task

In paragraph 9, the writer states that: “Making a rapid emotional assessment of the events of the moment is an extremely demanding job for the brain, animal or human” C. respond instantly to whatever is happening = making a rapid emotional assessment of the events of the moment.

Answer: C

25. Because of the language they have developed, humans…

Keywords: language, developed, humans

In paragraph 10, the writer states that: “All warm-blooded animals make constant tiny adjustments in arousal in response to external events, but humans, who have developed a much more complicated internal life as a result of language respond emotionally not only to their surroundings but to their own thoughts.” A. react to their own thoughts.

Answer: A

26. Individual responses to humour….

Keywords: individual, responses, humour

The last sentence of paragraph 10 states that: “Whether a joke gives pleasure or pain depends on a person”s outlook”. This means that what a person feels about a joke depends on his personal ideas and beliefs, his own views.

F. relate to a person”s subjective views

Answer: F

27. Peter derks believes that humour ….

Keywords: Peter Derks, believes, humour

The last sentence of paragraph 11 explains that: “If we can figure out how the mind processes humour, then we”ll have a pretty good handle on how it works in general”. Peter Derks believes that if we know how the mind/brain processes humour, we can know how the brain works in general. D. may provide valuable information about the operation of the brain.

What’s so funny? : Reading Answers

IELTS Academic Test – Passage 05: What’s so funny? reading answers with pdf summary. This reading paragraph has been taken from our huge collection of Academic & General Training (GT) Reading practice test PDF’s.

Check out What’s so funny? reading answers below with explanation and location given in the text:

IELTS reading module focuses on evaluating a candidate’s comprehension skills and ability to understand English. This is done by testing the reading proficiency through questions based on different structures and paragraphs (500-950 words each). There are 40 questions in total and hence it becomes extremely important to practice each and every question structure before actually sitting for the exam.

This reading passage mainly consists of following types of questions:

We are going to read about the science behind laughter and the idea of humour. You must read the passage carefully and try to answer all questions correctly.

What’s so funny?

John McCrone reviews recent research on humour…..

The joke comes over the headphones: ‘ Which side of a dog has the most hair? The left.’ No, not funny. Try again. ‘ Which side of a dog has the most hair? The outside.’ Hah! The punchline is silly yet fitting, tempting a smile, even a laugh. Laughter has always struck people as deeply mysterious, perhaps pointless. The writer Arthur Koestler dubbed it the luxury reflex: ‘unique in that it serves no apparent biological purpose’.

Theories about humour have an ancient pedigree. Plato expressed the idea that humour is simply a delighted feeling of superiority over others. Kant and Freud felt that joke-telling relies on building up a psychic tension which is safely punctured by the ludicrousness of the punchline. But most modern humour theorists have settled on some version of Aristotle’s belief that jokes are based on a reaction to or resolution of incongruity, when the punchline is either a nonsense or, though appearing silly, has a clever second meaning.

Graeme Ritchie, a computational linguist in Edinburgh, studies the linguistic structure of jokes in order to understand not only humour but language understanding and reasoning in machines. He says that while there is no single format for jokes, many revolve around a sudden and surprising conceptual shift. A comedian will present a situation followed by an unexpected interpretation that is also apt.

So even if a punchline sounds silly, the listener can see there is a clever semantic fit and that sudden mental ‘Aha!’ is the buzz that makes us laugh. Viewed from this angle, humour is just a form of creative insight, a sudden leap to a new perspective.

However, there is another type of laughter, the laughter of social appeasement and it is important to understand this too. Play is a crucial part of development in most young mammals. Rats produce ultrasonic squeaks to prevent their scuffles turning nasty. Chimpanzees have a ‘play-face’ – a gaping expression accompanied by a panting ‘ah, ah’ noise. In humans, these signals have mutated into smiles and laughs. Researchers believe social situations, rather than cognitive events such as jokes, trigger these instinctual markers of play or appeasement. People laugh on fairground rides or when tickled to flag a play situation, whether they feel amused or not.

Both social and cognitive types of laughter tap into the same expressive machinery in our brains, the emotion and motor circuits that produce smiles and excited vocalisations. However, if cognitive laughter is the product of more general thought processes, it should result from more expansive brain activity.

Psychologist Vinod Goel investigated humour using the new technique of ‘single event’ functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRl). An MRI scanner uses magnetic fields and radio waves to track the changes in oxygenated blood that accompany mental activity. Until recently, MRI scanners needed several minutes of activity and so could not be used to track rapid thought processes such as comprehending a joke. New developments now allow half-second ‘snapshots’ of all sorts of reasoning and problem-solving activities.

Making a rapid emotional assessment of the events of the moment is an extremely demanding job for the brain, animal or human. Energy and arousal levels may need, to be retuned in the blink of an eye. These abrupt changes will produce either positive or negative feelings. The orbital cortex, the region that becomes active in Goel’s experiment, seems the best candidate for the site that feeds such feelings into higher-level thought processes, with its close connections to the brain’s sub-cortical arousal apparatus and centres of metabolic control.

All warm-blooded animals make constant tiny adjustments in arousal in response to external events, but humans, who have developed a much more complicated internal life as a result of language, respond emotionally not only to their surroundings, but to their own thoughts. Whenever a sought-for answer snaps into place, there is a shudder of pleased recognition. Creative discovery being pleasurable, humans have learned to find ways of milking this natural response. The fact that jokes tap into our general evaluative machinery explains why the line between funny and disgusting, or funny and frightening, can be so fine. Whether a joke gives pleasure or pain depends on a person’s outlook.

Humour may be a luxury, but the mechanism behind it is no evolutionary accident. As Peter Derks, a psychologist at William and Mary College in Virginia, says: ‘I like to think of humour as the distorted mirror of the mind. It’s creative, perceptual, analytical and lingual. If we can figure out how the mind processes humour, then we’ll have a pretty good handle on how it works in general.

Questions 14-20

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 5?

In boxes 14-20 on your answer sheet, write:

TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

14. Arthur Koestler considered laughter biologically important in several ways.

15. Plato believed humour to be a sign of above-average intelligence.

16. Kant believed that a successful joke involves the controlled release of nervous energy.

17. Current thinking on humour has largely ignored Aristotle’s view on the subject.

18. Graeme Ritchie’s work links jokes to artificial intelligence.

19. Most comedians use personal situations as a source of humour.

20. Chimpanzees make particular noises when they are playing.

What’s so Funny? – IELTS Reading Answers

Updated On Mar 02, 2022

The Academic passage ‘What’s so Funny?’ is a reading passage that appeared in an IELTS Test.

It contains some of the IELTS reading question types. If you are interested in familiarising yourself with all the question types, don’t hesitate to take an IELTS reading practice test.

The question types found in this passage are:

True/False/Not Given Questions

True/False/Not Given questions are very tricky. This question consists of several statements – If the statement is present in the article as it is then you need to mark it as true. If the statement is found to be the opposite of the sentence which is there then it should be marked as false. If the statement given in the question is not at all present in the article then it should be marked as not given. Do not spend a lot of time finding the sentence which is not there.

Diagram Completion

In this Diagram completion questions, you’re given a descriptive text and a diagram or plan, which you have to label according to the text. Your diagram may be a technical drawing, a description of something from the natural world, a process or a plan of something.

Matching Sentence endings

In the Matching Sentence ending question, you will be given a list of unfinished sentences with no endings and a list of alternative endings for this question. Your task is to identify the correct endings to the incomplete sentences based on the reading text.

Read the passage below and answer questions 14-27. Beyond the questions, you will find the answers along with the location of the answers in the passage and the keywords that prove the answers.

What’s so Funny?

Answers

Signup/Login and get access to the answers

14 Answer: FALSE

Question Type: True/False and Not Given Questions

Answer location: Paragraph 1, line 6

Answer explanation: Paragraph 1 informs us that the writer ‘Arthur Koestler’ dubbed it (laughter) as the ‘luxury reflex’: ‘unique in that it serves ‘no apparent biological purpose‘’. As the statement contradicts the information, the answer is false.

15 Answer: NOT GIVEN

Question Type: True/False and Not Given Questions

Answer location: Paragraph 2, line 2

Answer explanation: Paragraph 2 expresses ‘Plato’s idea’ that humour is ‘simply a delighted feeling of superiority’ over others. There is no reference to above-average intelligence. Hence, the answer is not given

Question Type: True/False and Not Given Questions

Answer location: Paragraph 2, line 3

Answer explanation: Paragraph 2 mentions that ‘Kant’ and Freud felt that ‘joke-telling’ relies on building up a ‘psychic tension’ (nervous energy) which is ‘safely punctured’ (controlled release) by the ‘ludicrousness of the punchline’ (successful). As the statement agrees with the information, the answer is true.

17 Answer: FALSE

Question Type: True/False and Not Given Questions

Answer location: Paragraph 2, line 4

Answer explanation: Paragraph 2 informs us how ‘most modern humour theorists’ (current thinking on humour) have ‘settled on’ some version of ‘Aristotle’s belief’ (view) that ‘jokes are based on a reaction to or resolution of incongruity when the punchline is either nonsense or, though appearing silly’. As the statement contradicts the information, the answer is false.

18 Answer: TRUE

Question Type: True/False and Not Given Questions

Answer location: Paragraph 3, line 1

Answer explanation: Paragraph 3 cites ‘Graeme Ritchie’, a computational linguist in Edinburgh, and mentions that he studied the ‘linguistic structure of jokes’ in order to understand not only ‘humour’( jokes) but ‘language understanding’ and ‘reasoning in machines’ (artificial intelligence). As the statement agrees with the information, the answer is true.

19 Answer: NOT GIVEN

Question Type: True/False and Not Given Questions

Answer location: Paragraph 3, line 3

Answer explanation: In paragraph 3, it is given that ‘a comedian’ will ‘present a situation’ followed by ‘an unexpected interpretation that is also apt’. As there is no reference to personal situations as a source of humour, the answer is not given.

20 Answer: TRUE

Question Type: True/False and Not Given Questions

Answer location: Paragraph 5, line 4

Answer explanation: Paragraph 5 makes a reference to ‘chimpanzees’ having a ‘play-face’ (playing) – a gaping expression accompanied by a ‘panting ‘ah, ah’ noise’ (particular noises). As the statement agrees with the information, the answer is true.

21 Answer: Problem solving

Question Type: Diagram Completion

Answer location: Paragraph 8, line 2

Answer explanation: In Paragraph 8 Goel used a brain scanner and his scans showed that ‘at the beginning of a joke’ the listener’s ‘prefrontal cortex lit up’, particularly ‘the right prefrontal’ believed to be ‘critical for problem-solving’. Hence, the answer is ‘problem solving’.

22 Answer: temporal lobes

Question Type: Diagram Completion

Answer location: Paragraph 8, line 3

Answer explanation: Paragraph 8 points out that there was also ‘activity in the temporal lobes’ at the side of the head and in many other brain areas when there were consistent attempts to reuse stored knowledge. Hence, the answer is ‘temporal lobes’.

23 Answer: evaluating information

Question Type: Diagram Completion

Answer location: Paragraph 8, line 5

24 Answer: C

Question Type: Matching Sentence ending

Answer location: Paragraph 9, line 1

Answer explanation: Paragraph 9 mentions that making a ‘rapid emotional assessment of the events of the moment’ (respond instantly to whatever is happening) is an ‘extremely demanding job’ (one of the most difficult tasks) for ‘the brain’, animal or human. Hence, the answer is C (respond instantly to whatever is happening).

25 Answer: A

Question Type: Matching Sentence ending

Answer location: Paragraph 10, line 2

Answer explanation: In paragraph 10, the writer says that as ‘humans’ have ‘developed’ ‘language’, they ‘respond’ (react) emotionally not only to their surroundings but ‘to their own thoughts’. Hence, the answer is A (react to their own thoughts).

26 Answer: F

Question Type: Matching Sentence ending

Answer location: Paragraph 10, last line

Answer explanation: Paragraph 10 states that whether ‘a joke’ gives ‘pleasure or pain’ (individual responses) depends on a person’s outlook (subjective views). Hence, the answer is F (relate to a person’s subjective views).

27 Answer: D

Question Type: Matching Sentence ending

Answer location: Paragraph 11, line 2

Answer explanation: In the last paragraph, the writer mentions the belief of ‘Peter Derks’, a psychologist at William and Mary College in Virginia, that ‘humour’ can help to ‘figure out’ (provide) how the ‘mind’ (brain) processes humour. It will help to have a ‘pretty good handle’ (valuable information) on how ‘it’ (brain) ‘works in general’. Hence, the answer is D (may provide valuable information about the operation of the brain).

The joke comes over the headphones: ‘Which side of a dog has the most hair? The left.’ No, not funny. Try again. ‘Which side of a dog has the most hair? The outside.’ Hah! The punchline is silly yet fitting, tempting a smile, even a laugh. Laughter has always struck people as deeply mysterious, perhaps pointless. The writer Arthur Koestler dubbed it the luxury reflex: ‘unique in that it serves no apparent biological purpose’.

Theories about humour have an ancient pedigree. Plato expressed the idea that humour is simply a delighted feeling of superiority over others. Kant and Freud felt that joke-telling relies on building up a psychic tension which is safely punctured by the ludicrousness of the punchline. But most modern humour theorists have settled on some version of Aristotle’s belief that jokes are based on a reaction to or resolution of incongruity, when the punchline is either a nonsense or, though appearing silly, has a clever second meaning.

Graeme Ritchie, a computational linguist in Edinburgh, studies the linguistic structure of jokes in order to understand not only humour but language understanding and reasoning in machines. He says that while there is no single format for jokes, many revolve around a sudden and surprising conceptual shift. A comedian will present a situation followed by an unexpected interpretation that is also apt.

So even if a punchline sounds silly, the listener can see there is a clever semantic fit and that sudden mental ‘Aha!’ is the buzz that makes us laugh. Viewed from this angle, humour is just a form of creative insight, a sudden leap to a new perspective.

Both social and cognitive types of laughter tap into the same expressive machinery in our brains, the emotion and motor circuits that produce smiles and excited vocalisations. However, if cognitive laughter is the product of more general thought processes, it should result from more expansive brain activity.

Psychologist Vinod Goel investigated humour using the new technique of ‘single event’ functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRl). An MRI scanner uses magnetic fields and radio waves to track the changes in oxygenated blood that accompany mental activity. Until recently, MRI scanners needed several minutes of activity and so could not be used to track rapid thought processes such as comprehending a joke. New developments now allow half-second ‘snapshots’ of all sorts of reasoning and problem-solving activities.

Making a rapid emotional assessment of the events of the moment is an extremely demanding job for the brain, animal or human. Energy and arousal levels may need, to be retuned in the blink of an eye. These abrupt changes will produce either positive or negative feelings. The orbital cortex, the region that becomes active in Goel’s experiment, seems the best candidate for the site that feeds such feelings into higher-level thought processes, with its close connections to the brain’s sub-cortical arousal apparatus and centres of metabolic control.

All warm-blooded animals make constant tiny adjustments in arousal in response to external events, but humans, who have developed a much more complicated internal life as a result of language, respond emotionally not only to their surroundings, but to their own thoughts. Whenever a sought-for answer snaps into place, there is a shudder of pleased recognition. Creative discovery being pleasurable, humans have learned to find ways of milking this natural response. The fact that jokes tap into our general evaluative machinery explains why the line between funny and disgusting, or funny and frightening, can be so fine. Whether a joke gives pleasure or pain depends on a person’s outlook.

Humour may be a luxury, but the mechanism behind it is no evolutionary accident. As Peter Derks, a psychologist at William and Mary College in Virginia, says: ‘I like to think of humour as the distorted mirror of the mind. It’s creative, perceptual, analytical and lingual. If we can figure out how the mind processes humour, then we’ll have a pretty good handle on how it works in general.