What were the conquests of britain before normans

What were the conquests of britain before normans

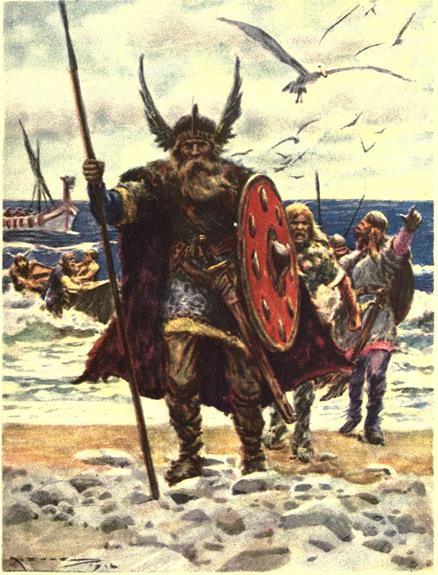

The period of the Scandinavian invasions

Viking invasions and settlements

Small scattered Viking raids began in the last years of the 8th century; in the 9th century large-scale plundering incursions were made in Britain and in the Frankish empire as well. Though Egbert defeated a large Viking force in 838 that had combined with the Britons of Cornwall and Aethelwulf won a great victory in 851 over a Viking army that had stormed Canterbury and London and put the Mercian king to flight, it was difficult to deal with an enemy that could attack anywhere on a long and undefended coastline. Destructive raids are recorded for Northumbria, East Anglia, Kent, and Wessex.

A large Danish army came to East Anglia in the autumn of 865, apparently intent on conquest. By 871, when it first attacked Wessex, it had already captured York, been bought off by Mercia, and had taken possession of East Anglia. Many battles were fought in Wessex, including one that led to a Danish defeat at Ashdown in 871. Alfred the Great, a son of Aethelwulf, succeeded to the throne in the course of the year and made peace; this gave him a respite until 876. Meanwhile the Danes drove out Burgred of Mercia, putting a puppet king in his place, and one of their divisions made a permanent settlement in Northumbria.

Alfred was able to force the Danes to leave Wessex in 877, and they settled northeastern Mercia; but a Viking attack in the winter of 878 came near to conquering Wessex. That it did not succeed is to be attributed to Alfred’s tenacity. He retired to the Somerset marshes, and in the spring he secretly assembled an army that routed the Danes at Edington. Their king, Guthrum, accepted Christianity and took his forces to East Anglia, where they settled.

The importance of Alfred’s victory cannot be exaggerated. It prevented the Danes from becoming masters of the whole of England. Wessex was never again in danger of falling under Danish control, and in the next century the Danish areas were reconquered from Wessex. Alfred’s capture of London in 886 and the resultant acceptance of him by all the English outside the Danish areas was a preliminary to this reconquest. That Wessex stood when the other kingdoms had fallen must be put down to Alfred’s courage and wisdom, to his defensive measures in reorganizing his army, to his building fortresses and ships, and to his diplomacy, which made the Welsh kings his allies. Renewed attacks by Viking hosts in 892–896, supported by the Danes resident in England, caused widespread damage but had no lasting success.

Alfred’s government and his revival of learning

Good internal government contributed to Alfred’s successful resistance to the Danes. He reorganized his finances and the services due from thegns, issued an important code of laws, and scrutinized carefully the exercise of justice. Alfred saw the Viking invasions as a punishment from God, especially because of a neglect of learning, without which men could not know and follow the will of God. He deplored the decay of Latin and enjoined its study by those destined for the church, but he also wished all young freemen of adequate means to learn to read English, and he aimed at supplying men with “the books most necessary for all men to know,” in their own language.

Alfred had acquired an education despite great difficulties, and he translated some books himself with the help of scholars from Mercia, the Continent, and Wales. Among them they made available works of Bede and Orosius, Gregory and Augustine, and the De consolatione philosophiae of Boethius. Compilation of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle began in his reign. The effects of Alfred’s educational reforms can be glimpsed in succeeding reigns, and his works continued to be copied. Only in his attempt to revive monasticism did he achieve little, for the monastic idea had lost its appeal—in England as well as on the Continent—during the Viking Age.

The achievement of political unity

The reconquest of the Danelaw

When Alfred died in 899, his son Edward succeeded him. A large-scale incursion by the Danes of Northumbria ended in their crushing defeat at Tettenhall in 910. Edward completed his father’s plan of building a ring of fortresses around Wessex, and his sister Aethelflaed took similar measures in Mercia. In 912 Edward was ready to begin the series of campaigns by which he relentlessly advanced into the Danelaw (Danish territory in England), securing each advance by a fortress, until he won back Essex, East Anglia, and the east-Midland Danish areas. Aethelflaed moved similarly against the Danish territory of the Five Boroughs (Derby, Leicester, Nottingham, Lincoln, and Stamford). She obtained Derby and Leicester and gained a promise of submission from the Northumbrian Danes before she died in 918. Edward had by then reached Stamford, but he broke off his advance to secure his acceptance by the Mercians at Tamworth and to prevent their setting up an independent kingdom. Then he took Nottingham, and all the Danes in Mercia submitted to him.

Meanwhile another danger had arisen: Norsemen from Ireland had been settling for some time west of the Pennines, and Northumbria was threatened by Raegnald, a Norse leader from Dublin, who made himself king at York in 919. Edward built fortresses at Thelwall and Manchester, and in 920 he received Raegnald’s submission, along with that of the Scots, the Strathclyde Welsh, and all the Northumbrians. Yet Norse kings reigned at York intermittently until 954.

The kingdom of England

Athelstan succeeded his father Edward in 924. He made terms with Raegnald’s successor Sihtric and gave him his sister in marriage. When Sihtric died in 927, Athelstan took possession of Northumbria, thus becoming the first king to have direct rule of all England. He received the submission of the kings of Wales and Scotland and of the English ruler of Northumbria beyond the Tyne.

Immediately after Athelstan’s death in 939 Olaf seized not only Northumbria but also the Five Boroughs. By 944 Athelstan’s successor, his younger brother Edmund, had regained control, and in 945 Edmund conquered Strathclyde and gave it to Malcolm of Scotland. But Edmund’s successor, Eadred, lost control of Northumbria for part of his reign to the Norse kings Erik Bloodax (son of Harald Fairhair) and Olaf Sihtricson. When Erik was killed in 954, Northumbria became a permanent part of the kingdom of England.

By becoming rulers of all England, the West Saxon kings had to administer regions with variant customs, governed under West Saxon, Mercian, or Danish law. In some parts of the area of Danish occupation, especially in northern England and the district of the Five Boroughs, the evidence of place-names, personal names, and dialect seems to indicate dense Danish settlement, but this has been seriously questioned; many “Danish” features are also found in Anglo-Saxon areas, and Danish names do not always prove Danish institutions. Moreover, the older Anglo-Saxon regions, such as Mercia, which often cut across both Danish and English areas, were politically more significant. Money, however, was calculated in marks and ores instead of shillings in Danish areas, and arable land was divided into plowlands and oxgangs instead of hides and virgates in the northern and northeastern parts of the Danelaw. Most important was the presence in some areas of a number of small landholders with a much greater degree of independence than their counterparts elsewhere; many ceorls had so suffered under the Danish ravages that they had bought a lord’s support by sacrificing some of their independence. Excavations (1976–81) have shown 10th-century Jorvik (York), a Danish settlement, to have been a centre of international trade, economic specialization, and town planning; it was on its way to becoming by 1086 (in the Domesday survey) one of Europe’s largest cities, numbering at least 2,000 households.

The kings did not try to eradicate the local peculiarities. King Edgar (reigned 959–975) expressly granted local autonomy to the Danes. But from Athelstan’s time it was decreed that there was to be one coinage for all the king’s dominion, and a measure of uniformity in administrative divisions was gradually achieved. Mercia became divided into shires on the pattern of those of Wessex. It is uncertain how early the smaller divisions of the shires were called “ hundreds,” but they now became universal (except in the northern Danelaw, where an area called a wapentake carried on its fiscal and jurisdictional functions). An ordinance of the mid-10th century laid down that the court in each hundred (called “hundred courts”) must meet every four weeks to handle local legal matters, and Edgar enjoined that the shire courts must meet twice a year and the borough courts three times. This pattern of local government survived the Norman Conquest.

The History of Roman Britain (43 AD — 410 AD). Part 4

From this article you will know about the times when the British Isles were covered with forests and the greater part of them was very misty and cold. The stormy sea roared round them, and few travellers dared to swim asross the sea to explore the far away land.

The History of Roman Britain (in short)

But there was a nation on the shores of the Mediterranean sea who were learned and powerful. That was the Roman nation. In the century just before Christ (B.C.) the great soldier and ruler, Julius Caesar, with his army visited Great Britain two summers running and decribed it to the civilised world.

Contents:

The Invasion of the Romans. Вторжение римлян

Julius Caesar (100BC — 44BC)

In the century BC the Romans were the great nation that succeeded in conquering many countries. First time in 55 BC the Roman emperor Julius Caesar at the head of the army of 10 thousand soldiers went to the British Isles. But they couldn’t conquer Britain and occupy the island. The channel storms and the Celts possessing iron-weapon made them retreat.

Next year Caesar repeated his invasion and succeeded. The 25-thousand army took possession of the probable capital Camulodunum (Colchester — Колчестер), as a result Celtic chiefs promised to pay tributes to the Romans. Soon Caesar left the country and never came back.

In fact Caesar did not conquer Britain and the promised tribute was not paid. The actual conquest took place 90 years later in 43 AD. At that time Britain was no longer a mysterious country as Caesar had written books about his travels and described many particulars about the Britons. Almost a hundred years later the Emperor Claudius (император Клавдий) began to conquer the country of the plains. His 50 thousand warriors landed in Kent (Кент), crossed the Thames and conquered the southeastern territory of the country.

The Celtic Revolts. Восстания кельтов

The Celtic tribal chiefs recognized the Romans as their rulers, which cannot be said about the people. Their discontent caused by endless plunder and heavy taxations grew. The first revolt took place in 51 AD. The wild tribes of the North were headed by Caradoc (Caractacus), who tried to resist the Roman rule. The attempt failed, the Romans defeated the Britons and secured the southern areas.

Another famous revolt was organized by Queen Boadicea. She headed the Celtic tribe of Iceni (inhabitants of contemporary Norfolk) in 61 AD. Boadicea rushed at the invaders in her chariot with her daughters beside her. At first the revolt was very successful. They started it when the current governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus was in the north of Wales leading a campaign against the island of Mona (modern Anglesey). Boadicea with her warriors managed to destroy Londinium (London), Camulodunum (Colchester) and Verulamium (St. Albans). During the revolt about 70 thousand Romans were killed. When this news reached Gaius Suetonius, he hurried back with his army and suppressed the rebellion. Boadicea did not want to become a prisoner, so she took poison together with her daughters. The name of the Queen Boadicea has remained in the history as well as in the people’s memory for her outstanding bravery. Her statue stands on the embankment by the Westminster Bridge in London.

The monument to the Queen Boadicea

Though the revolts failed, they had their result. It was not easy to suppress the revolts and now the Romans decided to think twice before violating Celtic people’s rights so aggressively.

Hadrian’s Wall. Вал Адриана

The Fall of Roman Britain. Падение римской Британии

Between the 3 d and the 4 th centuries the power of the Roman Empire gradually weakened. The end of the 4 th century was the time when the Germanic tribes started to invade the west of the Roman Empire. The safety of Rome itself was in question, and in the year of 407 the Roman legions were recalled from Britain.

The Romans came to Britain not to settle down there, and they did not return to Britain. The Celts were left alone absolutely leadless and defenseless.

During 410 years Britain was one of the remote provinces of the Roman Empire. This military occupation lasted 4 centuries and had a great influence on Britain.

Interesting facts — The Roman Influence on Britain

1. Language

Very few people could read or write in Britain. It was the Romans who brought language, writing and numbers to Britain. Nowadays you can find the marks of Roman influence in the English words of Latin origin, as we know the Romans spoke Latin. Among them are such words as school (schola), street (strata), port (porta), wall – (vallum), village (vicus), word “cheese” and “butter” also have Latin origin.

2. Roads

The Romans built first towns in Britain that were connected by Roman roads. The roads were made of mortal and gravel and were made so well they exist till now. These were long straight roads with milestones marking every mile (1000 paces).

Roman Milestone near Vindolanda (nothern England)

Roman Milestone near Vindolanda (nothern England)

3. Towns

Before the Romans there had been no towns in Britain. The Romans were the first to build towns. In the Roman towns there were market places where merchants sold their goods. There were also temples and public baths in most of the towns. Among the largest towns were London, York, Colchester, St. Albans, Lincoln and about 50 smaller towns.

The houses in Roman towns had central heating and running water: the rich had water pipes in their houses and the poor took water from the public fountains.

4. Roman Baths

The Romans loved baths and they brought this tradition to Britain. Baths were not just places for washing the body; it was a kind of entertainment and besides a luxurious entertainment.

A usual bath had mirrors along the walls and the ceiling was all in glass. The pool was made of rich marble and mosaics covered the floor.

The first Roman baths were built in Bath. In the picture you can see a Roman bath in the city of Bath, in Somerset.

Roman Bath in Sommerset

5. Roman London (AD 43 — AD 410)

In 61 AD the Boadicea with her supporters almost burn London to the ground. It took the Romans about 20 yeas to rebuild Londinium, since then the strong walls were built around London to ensure the safety of the city. This fort was situated where the Barbican centre is now.

Sources:

Ancient Britain

Invasion, Resistance, Settlement and Conquest

PRE CELTIC AND CELTIC PEOPLE. ANGLO-SAXON BRITAIN. INVASIONS OF THE VIKINGS. THE ENGLAND OF ALFRED THE GREAT. EDWARD THE CONFESSOR. THE BATTLE OF HASTINGS.

Key words, terms and concepts:

2. «Beaker» people

3. Celts, Druids, Celtic curves

4. Celtic languages – Gaelic and Brythonic

5. Roman Britain

6. Hadrian’s Wall

7. Scots and Picts

8. Queen Boadicea – (Boudicca)

10. Roman roads – straight as a die

11. Pax Romana, Roman Peace

12. Saxons: Saxon kings and Saxon kingdoms: Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Sussex, Wessex, Essex, Kent

14. Venerable Bede (731)

15. Alfred the Great (849-899)

17. Edward the Confessor (1042-1066)

The very first stages of the existence of people on the British Isles are frequenly described as prehistoric and referred to as unwritten history of Britain.

The geographical position of the land was both a blessing and a problem: on the one hand the insular position protected the country from invasions; and on the other – the lowland facing the continent always invited invasions.

The greatest material monument of the ancient population of the British Isles is Stonehenge on the Salisbury plain,– a monumental stone circle and a memorial of the Stone Age culture.

The first ever inhabitants are believed to be hunters of the Old Stone Age who came from the Continent, to be followed by new waves of imigrants.

By the end of the Stone Age the Beaker people who were called so after the clay mugs or «beakers» they could make,– were farmers and metal was already being used.

The beginning of the Stone Age coincided with the arrival of new invaders, mainly from France. They were the Celts. Reputed to be tall, fair and well built, they had artistic skills and were good craftsmen. Their dialects were imposed on the native population: the Gaelic form was spread in Ireland and Scotland, and the Brythonic in England and Wales. It was the Brythonic tribe of the Celts that gave its name to the whole country.

The culture of Celts in the Iron Age was not altogether barbaric. Their Priests, the Druids, were skillful in teaching and administration.

But the Romans came with a heavy hand,

And bridged and roaded and ruled the land.

wrote R. Kipling

The Roman Emperor Julius Caesar carried out two expeditions in 55 and 54 ВС, neither of which led to immediate Roman settlement in Britain. Caesar’s summer expeditions were a failure. Almost a century later in 43 AD Emperor Claudius sent his legions over the seas to occupy Britain. The occupation was to last more than three centuries and the Romans saw their mission of civilizing the country. The British were not conquered easily. There was a resistance in Wales and the Romans destroyed the Druids, a class of Celtic priests (or witchdoctors) as their rutuals alledgedly involved human sacrifice.

There was a revolt in East Anglia, where Queen Boadicea (Boudicca) and her daughters in their chariots were fighting against Roman soldiers and were defeated. The Roman occupation was spread mainly over England, while Wales, Scotland and Ireland remained unconquered areas of the Celtic fringe – preserving Celtic culture and traditions.

The Romans were in Great Britain for over 350 years, they were both an occupying army and the rulers. They imposed Pax Romana,– Roman peace – which stopped tribal wars, and protected Britain from the attacks of outsiders – Picts in the North, Saxons from overseas.

London is a Celtic name, but many towns that Romans built along their roads – Lancaster, Winchester, Chichester, etc. have the Latin component «castra»– a camp, a fortified town.

London was the centre of Roman Rule in Britain, it was walled, the Thames was bridged; and straight paved roads (Roman Roads,– that are as straight as a die) connected London with garrison towns.

Under the Emperor Hadrian in 120 AD a great wall was built across Britain between the Tyne and the Solway to protect the Romans against the attacks of Scots and Picts.

Hadrian’s wall was a vast engineering project and is a material monument of the Roman times alongside with roads, frescoes and mosaics on the villas and baths (in the city of Bath).

The Romans also brought Christianity to Britain and the British Church became a strong institution.

The native language absorbed many Latin words at that time.

By the fifth century the Roman Empire was beginning to disintegrate and the Roman legions in Britain had to return back to Rome to defend it from the attacks of the new waves of barbaric invaders. Britain was left to defend and rule itself.

Acceding to the writing of Venerable Bede, an English monk, barbaric teutonic tribes of Angles, Saxons and Jutes were making raids against the British throughout the fifth and sixth centuries. The British Celts tried to check the Germanic tribes, and that was the period of the half-legendary King Arthur and his knights of the Round Table who defended Christianity against the heathen Anglo-Saxons.

The Germanic invaders first arrived in small groups throughout the fifth century but managed to settle and oust the British population to the mountainous parts of the Isle of Great Britain.

The Anglo-Saxons controlled the central part of Britain which was described as England while the romanized Celts fled West taking with them their culture, language and Christianity.

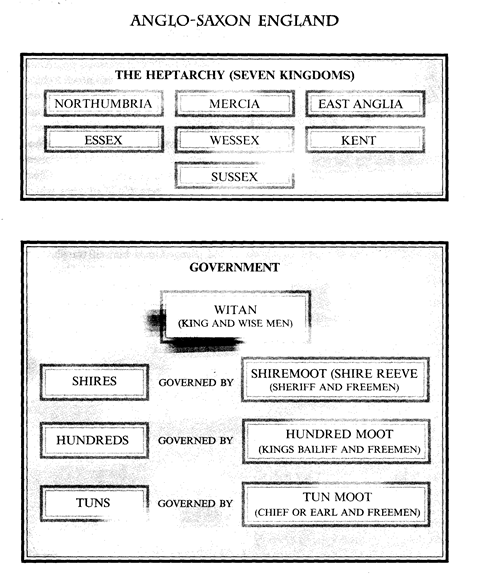

The Anglo-Saxon England was a network of small kingdoms.

The seventh century saw the establishment of seven kingdoms: Essex (East Saxons), Sussex (South Saxons), Wessex (West Saxons), East Anglia (East Angles), Kent, Mersia and Northumbria, and the largest three of them – Northumbria, Mercia and Wessex – dominated the country at different times.

The Anglo-Saxon kings were elected by the members of the Council of Chieftains (the Witan) and they ruled with the advice of the councilors, the great men of the kingdom. In time it became the custom to elect a member of the royal family, and the power of the king grew parallel to the size and the strength of his kingdom. In return for the support of his subjects,– who gave him free labour and military service, paid taxes and duties – the King gave them his protection and granted lands.

By the end of the eighth century the British Isles were subjected to one more invasion by nonChristian people from Scandinavia.

. But the Romans left

And the Danes blew in.

That’s where your history book begins.

Chart 1. Note how Anglo-Saxon England was divided into Seven Kingdoms, known as the Heptarchy. The chart shows how each Kingdom was split up, and how each part had its own moot, or council, to look after its affairs. The Witan was the council for the country.

This precious object in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, bears the words “Alfred had me made”. It is known as the Alfred Jewel and could really have been ordered by Alfred the Great.

They were called Norsemen or Danes, or the Vikings. The Vikings were brilliant sailors, they had the fastest boats in Europe, that were moving powered by sail. They crossed the Atlantic, and founded a colony in North America 500 years before Columbus. They had repeatedly raided the Eastern Coast of England, and by the middle of the ninth century almost all English Kingdoms were defeated by the Danes. In 870 only Wessex was left to resist the barbaric Danes. At that time the West Saxons got a new young King, his name was Alfred, later he was called Alfred the Great. And no other king has earned this title. Alfred forced the Danes to come to terms – to accept Christianity and live within the frontiers of the Danelaw – a large part of Eastern England, while he was master of the South and West of England.

King Alfred was quick to learn from his enemies: he created an efficient army and built a fleet of warships on a Danish pattern, which were known to have defeated Viking invaders at sea more than once. They were forced to go South and settle in Northern France, where their settlement became known as Normandy, the province of the Northmen. The England of King Alfred the Great received a new Code of laws which raised the standards of English society. New churches were built, foreign scholars were brought, schools were founded, King Alfred himself translated a number of books from Latin, including Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica and began the Anglo-Saxon chronicle, a year-by year history of England.

Alfred the Great saved England from the Danish conquest, but in the 10th– 11th centuries the Danes managed to expand their possesion in Great Britain and from 1013 to 1042 the Danish royal power triumphed in England. King al power triumphed in England. King Canut’s empire included Norway, Denmark and England. In 1042 the house of Wessex was restored to power in England, when Edward the Confessor was elected king by the Witan. He was half-Norman, had spent his exile in Normandy, and Wiffiam the Duke of Normandy was his cousin and a close friend.

Edward the Confessor was a religious monarch and devoted his attention to the construction of churches and most of all to the building of Westminster Abbey.

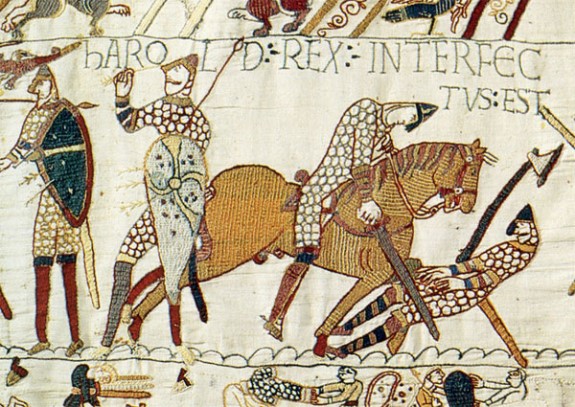

Edward the Confessor died in 1066 without an obvious heir. And the Witan elected Harold, a Saxon nobleman from the family of the Godwine, the king of England. Harold’s right to the English throne was challenged by William the Duke of Normandy who claimed the English Kingdom as his rightfull inherit ance which had been alledgedly promised to him by the late King Edward the Confessor.

1066 was a crucial year for the Saxon King, and for the history of the English.

Harold had to fight against two enemies at the same time. In the South William of Normandy was preparing to land in England, in the North, in Yorkshire, the Danes renewed their attacks against England.

Harold succeded in defeating the Danes and rushed his armies back to the South to meet William who had landed near Hastings. His men were tired, though they had done so well in the battle against the Danish vikings. William’s army was better armed, better organized and he had cavalry.

Had Harold waited and given his army a rest, the outcome of the battle might have been different.

The Bayeux tapestry tells the story of the Norman Conquest in picture and captions, like a comic. It took many hands and many month to make. The word on this piece say «King Harold is killed». It was once thought that the fird figure from the left represented Harold, and that Harold was killed by an arrow in the eye. But probably the fallen man farther right is the king.

But after a hard and long struggle Harold and his brothers were killed in the battle of Hastings and the flower of Saxon nobility lay dead together with them on the battle field.

The Bayeux Tapestry (231 feet long 19 inches wide) tells a complete story of the Norman Conquest of Saxon England in over seventy scenes. In one of the scenes the Latin writing says «Harold the King is dead», and under the inscription stands a man with an arrow in his eye believed to be King Harold.

William captured London and was crowned King of England in Westmister Abbey on Christmas Day, 1066.

The Norman period in English history had begun.

Some historians argue concerning possible ways of English history, had the Anglo-Saxons defeated William. But History doesn’t rely on the Conditional Mood.

All the invasions, raids and conquests were contributing new and new waves of peoples to be integrated into a newly appearing nation of the English, to understand which we must know its historical roots, studying historical facts.

1. What is traditionally said about the geographical position of Britain? What do you think of it?

2. What material monuments of Pre-Celtic population culture still exist on the British territory?

3. Which of the Celtic tribes gave their name to their new home-country?

4. What functions were performed by Celtic Priests? What were they called?

5. Which Roman expeditions were successful in subjugating Britain and when? Was it a peaceful development?

6. What are the well-recognized contributions of Roman civilisation to British culture?

7. Did King Arthur and his Knights of the Round table exist and when if they did?

9. What was the historical role of the Vikings on the British Isles?

10. Which of the Anglo-Saxon kings rightly deserved the title of Great? What were his great accomplishments?

11. In what way was Edward the Confessor responsible for William’s claim to the English crown?

12. What: is the name of the battle which is a historic turning point for England?

Понравилась статья? Поддержите нас донатом. Проект существует на пожертвования и доходы от рекламы

The Impact of the Norman Conquest of England

Article

The Norman conquest of England, led by William the Conqueror (r. 1066-1087 CE) was achieved over a five-year period from 1066 CE to 1071 CE. Hard-fought battles, castle building, land redistribution, and scorched earth tactics ensured that the Normans were here to stay. The conquest saw the Norman elite replace that of the Anglo-Saxons and take over the country’s lands, the Church was restructured, a new architecture was introduced in the form of motte and bailey castles and Romanesque cathedrals, feudalism became much more widespread, and the English language absorbed thousands of new French words, amongst a host of many other lasting changes which all combine to make the Norman invasion a momentous watershed in English history.

Conquest: Hastings to Ely

The conquest of England by the Normans started with the 1066 CE Battle of Hastings when King Harold Godwinson (aka Harold II, r. Jan-Oct 1066 CE) was killed and ended with William the Conqueror’s defeat of Anglo-Saxon rebels at Ely Abbey in East Anglia in 1071 CE. In between, William had to more or less constantly defend his borders with Wales and Scotland, repel two invasions from Ireland by Harold’s sons, and put down three rebellions at York.

Advertisement

The consequences of the Norman conquest were many and varied. Further, some effects were much longer-lasting than others. It is also true that society in England was already developing along its own path of history before William the Conqueror arrived and so it is not always so clear-cut which of the sometimes momentous political, social, and economic changes of the Middle Ages had their roots in the Norman invasion and which may well have developed under a continued Anglo-Saxon regime. Still, the following list summarises what most historians agree on as some of the most important changes the Norman conquest brought in England:

The Ruling Elite

The Norman conquest of England was not a case of one population invading the lands of another but rather the wresting of power from one ruling elite by another. There was no significant population movement of Norman peasants crossing the channel to resettle in England, then a country with a population of 1.5-2 million people. Although, in the other direction, many Anglo-Saxon warriors fled to Scandinavia after Hastings, and some even ended up in the elite Varangian Guard of the Byzantine emperors.

Advertisement

The lack of an influx of tens of thousands of Normans was no consolation for the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy, of course, as 20 years after Hastings there were only two powerful Anglo-Saxon landowners in England. Some 200 Norman nobles and 100 bishops and monasteries were given estates which had been distributed amongst 4,000 Anglo-Saxon landowners prior to 1066 CE. To ensure the Norman nobles did not abuse their power (and so threaten William himself), many of the old Anglo-Saxon tools of governance were kept in place, notably the sheriffs who governed in the king’s name the districts or shires into which England had traditionally been divided. The sheriffs were also replaced with Normans but they did provide a balance to Norman landowners in their jurisdiction.

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

The royal court and government became more centralised, indeed, more so than in any other kingdom in Europe thanks to the holding of land and resources by only a relatively few Norman families. Although William distributed land to loyal supporters, they did not typically receive any political power with their land. In a physical sense, the government was not centralised because William still did not have a permanent residence, preferring to move around his kingdom and regularly visit Normandy. The Treasury did, though, remain at Winchester and it was filled as a result of William imposing heavy taxes throughout his reign.

Motte & Bailey Castles

The Normans were hugely successful warriors and the importance they gave to cavalry and archers would affect English armies thereafter. Perhaps even more significant was the construction of garrisoned forts and castles across England. Castles were not entirely unknown in England prior to the conquest but they were then used only as defensive redoubts rather than a tool to control a geographical area. William embarked on a castle-building spree immediately after Hastings as he well knew that a protected garrison of cavalry could be the most effective method of military and administrative control over his new kingdom. From Cornwall to Northumbria, the Normans would build over 65 major castles and another 500 lesser ones in the decades after Hastings.

Advertisement

The Normans not only introduced a new concept of castle use but also military architecture to the British Isles: the motte and bailey castle. The motte was a raised mound upon which a fortified tower was built and the bailey was a courtyard surrounded by a wooden palisade which occupied an area around part of the base of the mound. The whole structure was further protected by an encircling ditch or moat. These castles were built in both rural and urban settings and, in many cases, would be converted into stone versions in the early 12th century CE. A good surviving example is the Castle Rising in Norfolk, but other, more famous castles still standing today which were originally Norman constructions include the Tower of London, Dover Castle in Kent, and Clifford’s Tower in York. Norman Romanesque cathedrals were also built (for example, at York, Durham, Canterbury, Winchester, and Lincoln), with the white stone of Caen being an especially popular choice of material, one used, too, for the Tower of London.

Domesday, Feudalism & the Peasantry

At the same time, there were new laws to ensure the Normans did not abuse their power, such as the crime of murder being applied to the unjustified killing of non-rebels or for personal gain and the introduction of trial by battle to defend one’s innocence. In essence, citizens were required to swear an oath of loyalty to the king, in return for which they received legal protection if they were wronged. Some of the new laws would be long-lasting, such as the favouring of the firstborn in inheritance claims, while others were deeply unpopular, such as William’s withdrawal of hunting rights in certain areas, notably the New Forest. Poachers were severely dealt with and could expect to be blinded or mutilated if caught. Another important change due to new laws regarded slavery, which was essentially eliminated from England by 1130 CE, just as it had been in Normandy.

Advertisement

Perhaps one area where hatred of all-things Norman was prevalent was the north of England. Following the rebellions against William’s rule there in 1067 and 1068 CE, the king spent the winter of 1069-70 CE ‘harrying’ the entire northern part of his kingdom from the west to east coast. This involved hunting down rebels, murders and mutilations amongst the peasantry, and the burning of crops, livestock, and farming equipment, which resulted in a devastating famine. As Domesday Book (see below) revealed, much of the northern lands were devastated and catalogued as worthless. It would take over a century for the region to recover.

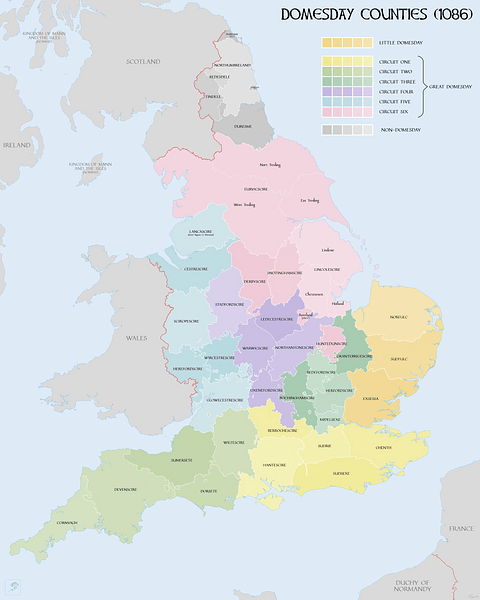

Domesday Book was compiled on William’s orders in 1086-7 CE, probably to find out for tax purposes exactly who owned what in England following the deaths of many Anglo-Saxon nobles over the course of the conquest and the giving out of new estates and titles by the king to his loyal followers. Indeed, Domesday Book reveals William’s total reshaping of land ownership and power in England. It was the most comprehensive survey ever undertaken in any medieval kingdom and is full of juicy statistics for modern historians to study such as the revelation that 90% of the population lived in the countryside and 75% of the people were serfs (unfree labourers).

A consequence of William’s land policies was the development (but not the origin of) feudalism. That is, William, who considered all the land in England his own personal property, gave out parcels of land (fiefs) to nobles (vassals) who in return had to give military service when required, such as during a war or to garrison castles and forts. Not necessarily giving service in person, a noble had to provide a number of knights depending on the size of the fief. The noble could have free peasants or serfs (aka villeins) work his lands, and he kept the proceeds of that labour. If a noble had a large estate, he could rent it out to a lesser noble who, in turn, had peasants work that land for him, thus creating an elaborate hierarchy of land ownership. Under the Normans, ecclesiastical landowners such as monasteries were similarly required to provide knights for military service.

Advertisement

The manorial system developed from its early Anglo-Saxon form under the Normans. Manorialism derives its name from the ‘manor’, the smallest piece of land which could support a single family. For administrative purposes, estates were divided into these units. Naturally, a powerful lord could own many hundreds of manors, either in the same place or in different locations. Each manor had free and/or unfree labour which worked on the land. The profits of that labour went to the landowner while the labourers sustained themselves by also working a small plot of land loaned to them by their lord. Following William’s policy of carving up estates and redistributing them, manorialism became much more widespread in England.

Trade & International Relations

The histories and even the cultures to some extent of France and England became much more intertwined in the decades after the conquest. Even as the King of England, William remained the Duke of Normandy (and so he had to pay homage to the King of France). The royal houses became even more interconnected following the reigns of William’s two sons (William II Rufus, r. 1087-1100 CE and Henry I, r. 1100-1135 CE) and the civil wars which broke out between rivals for the English throne from 1135 CE onwards. A side effect of this close contact was the significant modification over time of the Anglo-Saxon Germanic language, both the syntax and vocabulary being influenced by the French language. That this change occurred even amongst the illiterate peasantry is testimony to the fact that French was commonly heard spoken everywhere.

One specific area of international relations which greatly increased was trade. Before the conquest, England had had limited trade with Scandinavia, but as this region went into decline from the 11th century CE and because the Normans had extensive contacts across Europe (England was not the only place they conquered), then trade with the Continent greatly increased. Traders also relocated from the Continent, notably to places where they were given favourable customs arrangements. Thus places like London, Southampton, and Nottingham attracted many French merchant settlers, and this movement included other groups such as Jewish merchants from Rouen. Goods thus came and went across the English Channel, for example, huge quantities of English wool were exported to Flanders and wine was imported from France (although there is evidence it was not the best wine that country had to offer).

Conclusion

The Norman conquest of England, then, resulted in long-lasting and significant changes for both the conquered and the conquerors. The fate of the two countries of England and France would become inexorably linked over the following centuries as England became a much stronger and united kingdom within the British Isles and an influential participant in European politics and warfare thereafter. Even today, names of people and places throughout England remind of the lasting influence the Normans brought with them from 1066 CE onwards.

By Professor John Hudson

Last updated 2011-06-20

The Normans brought a powerful new aristocracy to Britain, and yet preserved much that was Anglo-Saxon about their new possession. What did they change and what did they leave?

On this page

Page options

Twin invasions

When Edward the Confessor died in 1066, he left a disputed succession. The throne was seized by his leading aristocrat, Harold Godwinson, who was rapidly crowned.

Harold defeated the Norwegian invasion at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in September 1066, but he was defeated and killed shortly afterwards at the Battle of Hastings, on 14 October in the same year.

At William’s death, his lands were divided, with his second son, William Rufus, becoming king of England.

The victorious William, now known as ‘the Conqueror’, brought a new aristocracy to England from Normandy and some other areas of France. He also strengthened aristocratic lordship and moved towards reform of the church.

At the same time, William was careful to preserve the powerful administrative machinery that had distinguished the regime of the late Anglo-Saxon kings.

At William’s death, his lands were divided, with his eldest son Robert taking control of Normandy, and his second son, William Rufus, becoming king of England.

Rufus successfully dealt with rebellions and with the threat of his elder brother (he defeated Robert during an invasion of Normandy), and maintained the powerful kingship of his father.

Following the death of Archbishop Lanfranc of Canterbury, good relations between king and church broke down, and the new archbishop, Anselm, became involved in quarrels with both Rufus and his successor Henry I.

Disputed succession

Rufus died in a hunting accident in the New Forest in 1100, and his younger brother, Henry, swiftly and successfully moved to seize the throne.

He further strengthened the ties of the Norman regime with the Anglo-Saxon past by marrying Edith (also known as Matilda), the great grand-daughter of Edmund Ironside, King of England.

In 1106, Henry succeeded in wresting control of Normandy from his brother, Robert, whom he thereafter kept imprisoned. While there continued to be conflict in Normandy, England experienced a lengthy peace during Henry’s reign.

The powerful royal government that had characterised earlier Norman kingship broke down.

At the same time, royal government continued to develop, notably in the field of royal financial accounting with the emergence of the ‘exchequer’.

Henry’s only legitimate son drowned in a shipwreck in 1120, and when the king died in 1135 the succession was again uncertain. Henry’s nephew, Stephen, count of Boulogne, seized the crown.

Matilda, Henry’s daughter, challenged Stephen’s position. She and her husband Geoffrey, Count of Anjou, enjoyed quite rapid success in Normandy, but in England an extended civil war developed. The powerful royal government that had characterised earlier Norman kingship broke down.

In 1153 it was agreed that Stephen should enjoy the throne for the rest of his life, but that he should be succeeded by Matilda’s son, Henry of Anjou.

The settlement might not have meant to have been observed, but Stephen died late in 1154, and Henry was crowned king. He thus added England to his extensive continental lands, which included Normandy, Anjou, and his wife Eleanor’s inheritance of Aquitaine.

Fresh conquests

The Normans also expanded into Scotland and Wales, although in a very different way from the conquest of England.

In Wales, aggressive Norman expansion was led largely by the aristocracy.

The kings and churchmen also brought the Scottish church more closely into line with that of Christendom further south. Malcolm and his wife Margaret founded the Benedictine monastery of Dunfermline, while David I introduced new monastic orders such the Cistercians and Premonstratensians.

There were significant periods of antagonism between Scottish and English kings, but also periods of peace such as in the time of David I of Scotland and Henry I of England.

Norman expansion into Wales took a different form still. Whereas in England the invasion was led by the duke, and in Scotland Normans were invited in by kings of the native line, in Wales, aggressive Norman expansion was led largely by the aristocracy.

Incursions took place all along the Anglo-Welsh border, but most notably in the north, from the earldom of Chester, and in the south. In the latter region emerged the Marcher lordships such as those of Pembroke and Ceredigion.

The English kings did participate in the process, and Henry I in particular was active in Wales. However, with the accession of Stephen in England there was a major reassertion of independent Welsh power.

Feudalism?

The economy of England had been expanding for at least a century before the Norman conquest, and was characterised by growing markets and sprawling towns.

By the 12th century, one of the ways in which English writers disparaged other peoples, notably the Welsh and Irish, was to depict their economies as primitive, as lacking markets, exchange and towns.

At the same time, kings and lords outside England deliberately sought to stimulate the wealth of their countries, as can be most clearly seen by the introduction of coinage and the establishment of boroughs by David I of Scotland and his successors.

The Domesday Book shows 11 leading members of the aristocracy held a quarter of the realm.

Within such an economy, there was clearly room for men to rise by increasing their wealth. At the same time, it remained a notably hierarchic society, and the process of conquest itself strengthened the role of lordship.

The Domesday Book, the product of William I’s great survey of his realm in 1086, shows that the 11 leading members of the aristocracy held about a quarter of the realm. Another quarter was in the hands of fewer than 200 other aristocrats.

In recent years there has been considerable debate about the problems arising from the use of the term ‘feudal’, a debate wittily foreseen by the great Victorian historian, FW Maitland, who said: ‘Feudalism is a useful word, and will cover a multitude of ignorances.’

Yet it would be wrong to see aristocracy and king, lordship and kingship as necessarily opposed. Kings and lords often regarded one another as natural companions, engaged in a mutually beneficial relationship.

In addition, in England both kings and aristocrats continued to operate in political and judicial arenas other than those defined by lordship. Most notable amongst these were the counties or shires that the Normans inherited from the Anglo-Saxons.

A thousand castles

The Normans had an enormous influence on architectural development in Britain. There had been large-scale fortified settlements, known as burghs, and also fortified houses in Anglo-Saxon England, but the castle was a Norman import.

Numbers are uncertain, but it seems plausible that about 1,000 castles had been built by the reign of Henry I, about four decades after the Norman conquest.

Some were towers on mounds surrounded by larger enclosures, often referred to as ‘motte and bailey castles’. Others were immense, most notably the huge palace-castles William I built at Colchester and London.

A lord might display his wealth, power and devotion through a combination of castle and church in close proximity.

These were the largest secular buildings in stone since the time of the Romans, over six centuries earlier. They were a celebration of William’s triumph, but also a sign of his need to overawe the conquered.

Churches were also built in great numbers, and in great variety, although usually in the Romanesque style with its characteristic round-topped arches.

The vast cathedrals of the late 11th and early 12th centuries, colossal in scale by European standards, emphasised the power of the Normans as well as their reform of the church in the conquered realm.

Buildings such as Durham cathedral suggest the strength and vibrancy of the builders’ culture in rather the same way as the early sky-scrapers of New York.

The Normans also continued the great building of parish churches, which had begun in England in the late Anglo-Saxon period. Such churches appeared too in the rest of the British Isles, and can still be seen, for example at Leuchars in Fife.

A lord might display his wealth, power and devotion through a combination of castle and church in close proximity, again as still spectacularly visible at Durham.

Find out more

Books

Battle of Hastings 1066 by MK Lawson (Tempus, 2003)

William the Conqueror by David Bates (Tempus, 2004)

About the author

John Hudson is Professor of Legal History in the Department of Mediaeval History, University of St Andrews. He is author of Land, Law, and Lordship in Anglo-Norman England (Oxford University Press, 1994) and The Formation of the English Common Law (Longmans, 1996). He has edited and translated a major twelfth-century chronicle, The History of the Church of Abingdon (two volumes, Oxford University Press, 2002, 2007) and is currently working on the volume of The Oxford History of the Laws of England covering the period 870-1220. His media contributions include interviews for Radio 4’s Making History and he is a member of the editorial advisory board for the BBC History Magazine.