In the first two jaws film what was the police chieds name

In the first two jaws film what was the police chieds name

Tropedia

Contents

Martin Brody

«You’re gonna need a bigger boat.»

Amity’s police chief who moved to the island with his family to get away from the dangers of living in New York. He hates water, and to his dismay he has to deal with one of its toothier inhabitants up-close-and-personal. twice.

Played by: Roy Scheider

Matt Hooper

«Mr. Vaughn, what we are dealing with here is a perfect engine, an eating machine.»

Shark-fascinated marine biologist who was called to Amity island to help with the shark problem. He starts of as a white-collared college kid foil to Quint’s blue collar gruffiness, but they come to an understanding with each other.

Played by: Richard Dreyfuss

Sam Quint

«Farewell and adieu to you fair Spanish ladies

Seaman with a bone to pick with all sharks, due to traumatizing events in World War II. He is hired to hunt down the shark with Brody and Hooper giving him assistance.

Played by: Robert Shaw

Ellen Brody

«I just want to know one thing; when do I get to become an islander?»

Martin’s loving wife, who offers emotional support to him when things are looking down. After he died, she was forced to deal with a killer shark that was specifiaclly targeting members of her family in the fourth film.

Played by: Lorraine Gary

Michael Brody

«White sharks are dangerous. I know ’em. My father, my brother, myself. They’re murderers.»

Oldest son in Brody family. Becomes the main focus of third and fourth film.

Played by: Chris Rebello (first film), Mrak Gruner (2), Dennis Quaid (3) and Lance Guest (The Revenge)

Sean Brody

Michael’s younger brother. He spends most of the time following his brother and is ultimately killed in the first minutes of The Revenge.

Played by: Jay Mello (first film), Marc Gilpin (2), John Putch (3) and Mitchell Anderson (The Revenge)

Mrs. Kintner

Alex Kintner

Chrissie

The shark’s first victim.

Vaughn

Amityville’s mayor who covers up the shark attaccks to keep the tourists coming.

The Sharks

The ones with the eponymous jaws. After the first shark swam into the waters of Amity Island, all members of the Brody family have found themselves confronting them in increasingly convoluted ways.

triviacountry.com

Popular Pages

More Info

Movie Trivia Quiz Questions And Answers

What famous role did both Cary Grant and Noel Coward reject?

A: James Bond

Tracey and Hepburn’s first film in 1942 was titled what?

A: Woman of the Year

What actor was known as Singing Sandy early in his career?

A: John Wayne

In «The Left Handed Gun» Paul Newman played who?

A: Billy the Kid

What car did Caractacus Potts drive?

A: Chitty Chitty Bang Bang

What was the name of James Bonds secretary?

A: Loelia Ponsonby

Mary Catherine Collins scored acting success as who?

A: Bo Derek

In the movie Star Wars, what is the Emperors last name?

A: Palpatine

What film was the last sequel to win a best picture award?

A: Silence of the Lambs

Who was the director of Four Weddings and a Funeral?

A: Mike Newell

In 1908, A’Ecu d’Or became the world’s first what?

A: Pornographic movie

What actress in the film Goldfinger was painted gold?

A: Shirley Eaton

Who was it who once said «I have had a talent for irritating women since I was 14»?

A: Marilyn Monroe

What was Clint Eastwoods first film, made in 1955?

A: Francis in the Navy

Which director directed the movie of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451?

A: Francois Trufeau

William Hurt won the best actor Oscar for what 1985 movie?

A: The Kiss of the Spiderwoman

Raquel Welch once had a job as a what?

A: Weathergirl

In the first two Jaws film, what was the police chiefs name?

A: Martin Brody

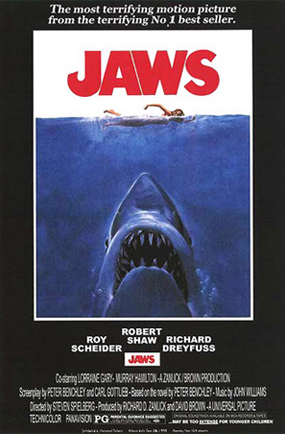

Jaws (Film)

Directed by:

Produced by:

Screenplay by:

Based on:

Starring:

Robert Shaw

Richard Dreyfuss

Lorraine Gary

Murray Hamilton

Music by:

Cinematography by:

Edited by:

Production company:

Distribution by:

Release date:

Running time:

Country:

Language:

Budget:

Box Office:

Shot mostly on location on Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts, the film had a troubled production, going over budget and past schedule. As the art department’s mechanical sharks suffered many malfunctions, Spielberg decided to mostly suggest the animal’s presence, employing an ominous, minimalistic theme created by composer John Williams to indicate the shark’s impending appearances. Spielberg and others have compared this suggestive approach to that of classic thriller director Alfred Hitchcock. Universal Pictures gave the film what was then an exceptionally wide release for a major studiopicture, over 450 screens, accompanied by an extensive marketing campaign with a heavy emphasis on television spots and tie-in merchandise.

Now considered one of the greatest films ever made, Jaws was the prototypical summer blockbuster, with its release regarded as a watershed moment in motion picture history. Jaws became the highest-grossing film of all time until the release of Star Wars (1977). It won several awards for its soundtrack and editing. Along with Star Wars, Jaws was pivotal in establishing the modern Hollywood business model, which revolves around high box-office returns from action and adventure pictures with simple «high-concept» premises that are released during the summer in thousands of theaters and supported by heavy advertising. It was followed by three sequels, none with the participation of Spielberg or Benchley, and many imitative thrillers. In 2001, Jaws was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the United States National Film Registry, being deemed «culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant».

Contents

Plot Synopsis [ ]

When local fishermen catch a large tiger shark, the mayor proclaims the beaches safe. Hooper disputes it being the same predator, confirming this after no human remains are found inside it. Hooper and Brody find a half-sunken vessel belonging to local fisherman Ben Gardner while searching the night waters in Hooper’s boat. Underwater, the investigating Hooper retrieves a sizable great white shark’s tooth embedded in the submerged hull. He drops it after finding Gardner’s partial corpse. Vaughn discounts Brody and Hooper’s claims that a huge great white shark is responsible and refuses to close the beaches, allowing only added safety precautions. On the Fourth of July weekend, tourists pack the beaches. Following a juvenile prank, the real shark enters a nearby estuary, killing a boater and causing Brody’s son, Michael, to go into shock. Brody finally convinces a devastated Vaughn to hire Quint.

Quint, Brody, and Hooper set out on Quint’s boat, the Orca, to hunt the shark. While Brody lays down a chum line, Quint waits for an opportunity to hook the shark. Without warning, it appears behind the boat. Quint estimates the shark to be 25 feet (7.6 m) long weighing 3 tons and then harpoons a barrel into it, but it drags the barrel underwater and disappears.

At nightfall, as the three swap stories, the great white returns unexpectedly, ramming the boat’s hull and killing the power. The men work through the night repairing the engine. In the morning, Brody attempts to call the Coast Guard, but Quint smashes the radio, enraging Brody. After a long chase, Quint harpoons another barrel into the shark. The line is tied to the stern, but the shark drags the boat backwards, swamping the deck and flooding the engine compartment, forcing Quint to sever the line to prevent the transom from being pulled out. He then heads toward shore, intending to lure the shark to shallower waters and suffocate it, but the overtaxed engine quits.

With the Orca slowly sinking, the trio attempt a riskier approach: Hooper dons scuba gear and enters the water in a shark-proof cage, intending to lethally inject the shark with strychnine using a hypodermic spear. The shark demolishes the cage before Hooper can inject it, but he manages to escape to the seabed. The shark then attacks the boat directly, killing Quint. Trapped on the sinking vessel, Brody stuffs a pressurized scuba tank into the shark’s mouth, and, climbing the mast, shoots the tank with Quint’s rifle, destroying it. The resulting explosion obliterates the shark. Hooper resurfaces, and he and Brody paddle to Amity Island clinging to boat wreckage.

Production [ ]

Development [ ]

To direct, Zanuck and Brown first considered veteran filmmaker John Sturges—whose résumé included another maritime adventure, The Old Man and the Sea —before offering the job to Dick Richards, whose directorial debut, The Culpepper Cattle Co. had come out the previous year. However, they grew irritated by Richards’s habit of describing the shark as a whale and soon dropped him from the project. Meanwhile, Steven Spielberg very much wanted the job. The 26-year-old had just directed his first theatrical film, The Sugarland Express, for Zanuck and Brown. At the end of a meeting in their office, Spielberg noticed their copy of the still-unpublished Benchley novel, and after reading it was immediately captivated. He later observed that it was similar to his 1971 television film Duel in that both deal with «these leviathans targeting everymen». After Richards’s departure, the producers signed Spielberg to direct in June 1973, before the release of The Sugarland Express.

Writing [ ]

For the screen adaptation, Spielberg wanted to stay with the novel’s basic plot, while omitting Benchley’s many subplots, such as the mayor having connections to the mafia. He declared that his favorite part of the book was the shark hunt on the last 120 pages, and told Zanuck when he accepted the job, «I’d like to do the picture if I could change the first two acts and base the first two acts on original screenplay material, and then be very true to the book for the last third.» When the producers purchased the rights to his novel, they promised Benchley that he could write the first draft of the screenplay. The intent was to make sure a script could be done despite an impending threat of a Writer’s Guild strike, given Benchley was not unionized. Overall, he wrote three drafts before the script was turned over to other writers; delivering his final version to Spielberg, he declared, «I’m written out on this, and that’s the best I can do.» Benchley would later describe his contribution to the finished film as «the storyline and the ocean stuff – basically, the mechanics», given he «didn’t know how to put the character texture into a screenplay.» One of his changes was to remove the novel’s adulterous affair between Ellen Brody and Matt Hooper, at the suggestion of Spielberg, who feared it would compromise the camaraderie between the men on the Orca. During the film’s production, Benchley agreed to return and play a small onscreen role as a reporter.

Spielberg, who felt that the characters in Benchley’s script were still unlikable, invited the young screenwriter John Byrum to do a rewrite, but he declined the offer. Columbo creators William Link and Richard Levinson also declined Spielberg’s invitation. Tony and Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright Howard Sackler was in Los Angeles when the filmmakers began looking for another writer and offered to do an uncredited rewrite; since the producers and Spielberg were unhappy with Benchley’s drafts, they quickly agreed. At the suggestion of Spielberg, Brody’s characterization made him afraid of water, «coming from an urban jungle to find something more terrifying off this placid island near Massachusetts.»

Spielberg wanted «some levity» in Jaws, humor that would avoid making it «a dark sea hunt», so he turned to his friend Carl Gottlieb, a comedy writer-actor then working on the sitcom The Odd Couple. Spielberg sent Gottlieb a script, asking what the writer would change and if there was a role he would be interested in performing. Gottlieb sent Spielberg three pages of notes, and picked the part of Meadows, the politically connected editor of the local paper. He passed the audition one week before Spielberg took him to meet the producers regarding a writing job.

While the deal was initially for a «one-week dialogue polish», Gottlieb eventually became the primary screenwriter, rewriting the entire script during a nine-week period of principal photography. The script for each scene was typically finished the night before it was shot, after Gottlieb had dinner with Spielberg and members of the cast and crew to decide what would go into the film. Many pieces of dialogue originated from the actors’ improvisations during these meals; a few were created on set, most notably Roy Scheider’s ad-lib of the line «You’re gonna need a bigger boat.» John Milius contributed dialogue polishes, and Sugarland Express writers Matthew Robbins and Hal Barwood also made uncredited contributions. Spielberg has claimed that he prepared his own draft, although it is unclear to what degree the other screenwriters drew on his material. One specific alteration he called for in the story was to change the cause of the shark’s death from extensive wounds to a scuba tank explosion, as he felt audiences would respond better to a «big rousing ending». The director estimated the final script had a total of 27 scenes that were not in the book.

Benchley had written Jaws after reading about sport fisherman Frank Mundus’s capture of an enormous shark in 1964. According to Gottlieb, Quint was loosely based on Mundus, whose book Sportfishing for Sharks he read for research. Sackler came up with the backstory of Quint as a survivor of the World War II USS Indianapolisdisaster. The question of who deserves the most credit for writing Quint’s monologue about the Indianapolis has caused substantial controversy. Spielberg described it as a collaboration between Sackler, Milius, and actor Robert Shaw, who was also a playwright. According to the director, Milius turned Sackler’s «three-quarters of a page» speech into a monologue, and that was then rewritten by Shaw. Gottlieb gives primary credit to Shaw, downplaying Milius’s contribution.

The role of Brody was offered to Robert Duvall, but the actor was interested only in portraying Quint. Charlton Heston expressed a desire for the role, but Spielberg felt that Heston would bring a screen persona too grand for the part of a police chief of a modest community. Roy Scheider became interested in the project after overhearing Spielberg at a party talk with a screenwriter about having the shark jump up onto a boat. Spielberg was initially apprehensive about hiring Scheider, fearing he would portray a «tough guy», similar to his role in The French Connection.

Nine days before the start of production, neither Quint nor Hooper had been cast. The role of Quint was originally offered to actors Lee Marvin and Sterling Hayden, both of whom passed. Zanuck and Brown had just finished working with Robert Shaw on The Sting, and suggested him to Spielberg. Shaw was reluctant to take the role since he did not like the book, but decided to accept at the urging of both his wife, actress Mary Ure, and his secretary—»The last time they were that enthusiastic was From Russia with Love. And they were right.» Shaw based his performance on fellow cast member Craig Kingsbury, a local fisherman, farmer, and legendary eccentric, who was playing fisherman Ben Gardner. Spielberg described Kingsbury as «the purest version of who, in my mind, Quint was», and some of his offscreen utterances were incorporated into the script as lines of Gardner and Quint. Another source for some of Quint’s dialogue and mannerisms, especially in the third act at sea, was Vineyard mechanic and boat-owner Lynn Murphy.

For the role of Hooper, Spielberg initially wanted Jon Voight. Timothy Bottoms, Joel Grey, and Jeff Bridges were also considered for the part. Spielberg’s friend George Lucas suggested Richard Dreyfuss, whom he had directed in American Graffiti. The actor initially passed, but changed his decision after he attended a pre-release screening of The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, which he had just completed. Disappointed in his performance and fearing that no one would want to hire him once Kravitz was released, he immediately called Spielberg and accepted the role in Jaws. Because the film the director envisioned was so dissimilar to Benchley’s novel, Spielberg asked Dreyfuss not to read it. As a result of the casting, Hooper was rewritten to better suit the actor, as well as to be more representative of Spielberg, who came to view Dreyfuss as his «alter ego».

Filming [ ]

Principal photography began May 2, 1974, on the island of Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, selected after consideration was given to eastern Long Island. Brown explained later that the production «needed a vacation area that was lower middle class enough so that an appearance of a shark would destroy the tourist business.» [41] Martha’s Vineyard was also chosen because the surrounding ocean had a sandy bottom that never dropped below 35 feet (11 m) for 12 miles (19 km) out from shore, which allowed the mechanical sharks to operate while also beyond sight of land. As Spielberg wanted to film the aquatic sequences relatively close-up to resemble what people see while swimming, cinematographer Bill Butler devised new equipment to facilitate marine and underwater shooting, including a rig to keep the camera stable regardless of tide and a sealed submersible camera box. Spielberg asked the art department to avoid red in both scenery and wardrobe, so that the blood from the attacks would be the only red element and cause a bigger shock.

Shooting at sea led to many delays: unwanted sailboats drifted into frame, cameras got soaked, and the Orca once began to sink with the actors on board. The prop sharks frequently malfunctioned owing to a series of problems including bad weather, pneumatic hoses taking on salt water, frames fracturing due to water resistance, corroding skin, and electrolysis. From the first water test onward, the «non-absorbent» neoprene foam that made up the sharks’ skin soaked up liquid, causing the sharks to balloon, and the sea-sled model frequently got entangled among forests of seaweed. Spielberg later calculated that during the 12-hour daily work schedule, on average only four hours were actually spent filming. Gottlieb was nearly decapitated by the boat’s propellers, and Dreyfuss was almost imprisoned in the steel cage. The actors were frequently seasick. Shaw also fled to Canada whenever he could due to tax problems, engaged in binge drinking, and developed a grudge against Dreyfuss, who was getting rave reviews for his performance in Duddy Kravitz. Editor Verna Fields rarely had material to work with during principal photography, as according to Spielberg «we would shoot five scenes in a good day, three in an average day, and none in a bad day.»

The mechanical shark, attached to the tower

The delays proved beneficial in some regards. The script was refined during production, and the unreliable mechanical sharks forced Spielberg to shoot many scenes so that the shark was only hinted at. For example, for much of the shark hunt, its location is indicated by the floating yellow barrels. The opening had the shark devouring Chrissie, but it was rewritten so that it would be shot with Backlinie being dragged and yanked by cables to simulate an attack. Spielberg also included multiple shots of just the dorsal fin. This forced restraint is widely thought to have added to the film’s suspense. As Spielberg put it years later, «The film went from a Japanese Saturday matinee horror flick to more of a Hitchcock, the less-you-see-the-more-you-get thriller.» In another interview, he similarly declared, «The shark not working was a godsend. It made me become more like Alfred Hitchcock than like Ray Harryhausen.» The acting became crucial for making audiences believe in such a big shark: «The more fake the shark looked in the water, the more my anxiety told me to heighten the naturalism of the performances.»

Footage of real sharks was shot by Ron and Valerie Taylor in the waters off Dangerous Reef in South Australia, with a short actor in a miniature shark cage to create the illusion that the sharks were enormous. During the Taylors’ shoot, a great white attacked the boat and cage. The footage of the cage attack was so stunning that Spielberg was eager to incorporate it in the film. No one had been in the cage at the time, however, and the script, following the novel, originally had the shark killing Hooper in it. The storyline was consequently altered to have Hooper escape from the cage, which allowed the footage to be used. As production executive Bill Gilmore put it, «The shark down in Australia rewrote the script and saved Dreyfuss’s character.»

Music [ ]

John Williams composed the film’s score, which earned him an Academy Award and was later ranked the sixth-greatest score by the American Film Institute. The main «shark» theme, a simple alternating pattern of two notes— variously identified as «E and F» [70] or «F and F sharp» — became a classic piece of suspense music, synonymous with approaching danger (see leading-tone). Williams described the theme as «grinding away at you, just as a shark would do, instinctual, relentless, unstoppable.» The piece was performed by tuba player Tommy Johnson. When asked by Johnson why the melody was written in such a high register and not played by the more appropriate French horn, Williams responded that he wanted it to sound «a little more threatening». When Williams first demonstrated his idea to Spielberg, playing just the two notes on a piano, Spielberg was said to have laughed, thinking that it was a joke. As Williams saw similarities between Jaws and pirate movies, at other points in the score he evoked «pirate music», which he called «primal, but fun and entertaining». Calling for rapid, percussive string playing, the score contains echoes of La mer by Claude Debussy as well of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring.

There are various interpretations of the meaning and effectiveness of the primary music theme, which is widely described as one of the most recognizable cinematic themes of all time. Music scholar Joseph Cancellaro proposes that the two-note expression mimics the shark’s heartbeat. According to Alexandre Tylski, like themes Bernard Herrmann wrote for Taxi Driver, North by Northwest, and particularly Mysterious Island, it suggests human respiration. He further argues that the score’s strongest motif is actually «the split, the rupture»—when it dramatically cuts off, as after Chrissie’s death. The relationship between sound and silence is also taken advantage of in the way the audience is conditioned to associate the shark with its theme, which is exploited toward the film’s climax when the shark suddenly appears with no musical introduction.

Spielberg later said that without Williams’s score the film would have been only half as successful, and according to Williams it jumpstarted his career. He had previously scored Spielberg’s debut feature, The Sugarland Express, and went on to collaborate with the director on almost all of his films. The original soundtrack for Jaws was released by MCA Records on LP in 1975, and as a CD in 1992, including roughly a half hour of music that Williams redid for the album. In 2000, two versions of the score were released: Decca/Universal reissued the soundtrack album to coincide with the release of the 25th-anniversary DVD, featuring the entire 51 minutes of the original score, and Varèse Sarabande put out a rerecording of the score performed by the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, conducted by Joel McNeely.

Inspiration and Themes [ ]

The underwater scenes shot from the shark’s point of view have been compared with passages in two 1950s horror films, Creature from the Black Lagoon and The Monster That Challenged the World. Gottlieb named two science fiction productions from the same era as influences on how the shark was depicted, or not: The Thing from Another World, which Gottlieb described as «a great horror film where you only see the monster in the last reel»; and It Came From Outer Space, where «the suspense was built up because the creature was always off-camera». Those precedents helped Spielberg and Gottlieb to «concentrate on showing the ‘effects’ of the shark rather than the shark itself». Scholars such as Thomas Schatz described how Jaws melds various genres while essentially being an action film and a thriller. Most is taken from horror, with the core of a nature-based monster movie while adding elements of a slasher film. The second half provides a buddy film in the interaction between the crew of the Orca, and a supernatural horror based on the shark’s depiction of a nearly Satanic menace.

Critics such as Neil Sinyard have described similarities to Henrik Ibsen’s play An Enemy of the People. Gottlieb himself said he and Spielberg referred to Jaws as «Moby-Dick meets Enemy of the People«. The Ibsen work features a doctor who discovers that a seaside town’s medicinal hot springs, a major tourist attraction and revenue source, are contaminated. When the doctor attempts to convince the townspeople of the danger, he loses his job and is shunned. This plotline is paralleled in Jaws by Brody’s conflict with Mayor Vaughn, who refuses to acknowledge the presence of a shark that may dissuade summer beachgoers from coming to Amity. Brody is vindicated when more shark attacks occur at the crowded beach in broad daylight. Sinyard calls the film a «deft combination of Watergate and Ibsen’s play».

Scholarly criticism [ ]

Jaws has received attention from academic critics. Stephen Heath relates the film’s ideological meanings to the then-recent Watergate scandal. He argues that Brody represents the «white male middle class—[there is] not a single black and, very quickly, not a single woman in the film», who restores public order «with an ordinary-guy kind of heroism born of fear-and-decency». Yet Heath moves beyond ideological content analysis to examine Jaws as a signal example of the film as «industrial product» that sells on the basis of «the pleasure of cinema, thus yielding the perpetuation of the industry (which is why part of the meaning of Jaws is to be the most profitable movie)».

Andrew Britton contrasts the film to the novel’s post-Watergate cynicism, suggesting that its narrative alterations from the book (Hooper’s survival, the shark’s explosive death) help make it «a communal exorcism, a ceremony for the restoration of ideological confidence.» He suggests that the experience of the film is «inconceivable» without the mass audience’s jubilation when the shark is annihilated, signifying the obliteration of evil itself. In his view, Brody serves to demonstrate that «individual action by the one just man is still a viable source for social change». Peter Biskind argues that the film does maintain post-Watergate cynicism concerning politics and politicians insofar as the sole villain beside the shark is the town’s venal mayor. Yet he observes that, far from the narrative formulas so often employed by New Hollywoodfilmmakers of the era—involving Us vs. Them, hip counterculture figures vs. «The Man»—the overarching conflict in Jaws does not pit the heroes against authority figures, but against a menace that targets everyone regardless of socioeconomic position.

Neal Gabler analyzed the film as showing three different approaches to solving an obstacle: science (represented by Hooper), spiritualism (represented by Quint), and the common man (represented by Brody). The last of the three is the one which succeeds and is in that way endorsed by the film.

Release [ ]

Promotion [ ]

More merchandise was created to take advantage of the film’s release. In 1999, Graeme Turner wrote that Jaws was accompanied by what was still «probably the most elaborate array of tie-ins» of any film to date: «This included a sound-track album, T-shirts, plastic tumblers, a book about the making of the movie, the book the movie was based on, beach towels, blankets, shark costumes, toy sharks, hobby kits, iron-transfers, games, posters, shark’s tooth necklaces, sleepwear, water pistols, and more.» The Ideal Toy Company, for instance, produced a game in which the player had to use a hook to fish out items from the shark’s mouth before the jaws closed.

Theatrical run [ ]

The glowing audience response to a rough cut of the film at two test screenings in Dallas on March 26, 1975, and one in Long Beach, on March 28, along with the success of Benchley’s novel and the early stages of Universal’s marketing campaign, generated great interest among theater owners, facilitating the studio’s plan to debut Jaws at hundreds of cinemas simultaneously. A third and final preview screening, of a cut incorporating changes inspired by the previous presentations, was held in Hollywood on April 24. After Universal chairman Lew Wasserman attended one of the screenings, he ordered the film’s initial release—planned for a massive total of as many as 900 theaters—to be cut down, declaring, «I want this picture to run all summer long. I don’t want people in Palm Springs to see the picture in Palm Springs. I want them to have to get in their cars and drive to see it in Hollywood.» Nonetheless, the several hundred theaters that were still booked for the opening represented what was then an unusually wide release. At the time, wide openings were associated with movies of doubtful quality; not uncommon on the exploitation side of the industry, they were customarily employed to diminish the effect of negative reviews and word of mouth. There had been some recent exceptions, including the rerelease of Billy Jack and the original release of its sequel The Trial of Billy Jack, the Dirty Harry sequel Magnum Force, and the latest installments in the James Bond series. Still, the typical major studio film release at the time involved opening at a few big-city theaters, which allowed for a series of premieres. Distributors would then slowly forward prints to additional locales across the country, capitalizing on any positive critical or audience response. The outsized success of The Godfather in 1972 had sparked a trend toward wider releases, but even that film had debuted in just five theaters, before going wide in its second weekend.

On June 20, Jaws opened across North America on 464 screens—409 in the United States, the remainder in Canada. The coupling of this broad distribution pattern with the movie’s then even rarer national television marketing campaign yielded a release method virtually unheard-of at the time. (A month earlier, Columbia Pictureshad done something similar with a Charles Bronson thriller, Breakout, though that film’s prospects for an extended run were much slimmer.) Universal president Sid Sheinberg reasoned that nationwide marketing costs would be amortized at a more favorable rate per print relative to a slow, scaled release. Building on the film’s success, the release was subsequently expanded on July 25 to nearly 700 theaters, and on August 15 to more than 950. [117] Overseas distribution followed the same pattern, with intensive television campaigns and wide releases—in Great Britain, for instance, Jaws opened in December at more than 100 theaters.

For its fortieth anniversary, the film was released in selected theaters (across approximately 500 theaters) in the United States on Sunday, June 21 and Wednesday, June 24, 2015.

Reception [ ]

Box office performance [ ]

On television, the American Broadcasting Company aired it for the first time right after its 1979 re-release. The first U.S. broadcast attracted 57 percent of the total audience, the second highest televised movie share at the time behind Gone with the Wind. In the United Kingdom, 23 million people watched its inaugural broadcast in October 1981, the second biggest TV audience ever for a feature film behind Live and Let Die.

Critical response [ ]

Accolades [ ]

Jaws won three Academy Awards for Best Film Editing, Best Original Dramatic Score, and Best Sound (Robert Hoyt, Roger Heman, Earl Madery and John Carter). It was also nominated for Best Picture, losing to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Spielberg greatly resented the fact that he was not nominated for Best Director. Along with the Oscar, John Williams’s score won the Grammy Award, the BAFTA Award for Best Film Music, and the Golden Globe Award. To her Academy Award, Verna Fields added the American Cinema Editors’ Eddie Award for Best Edited Feature Film.

Jaws was chosen Favorite Movie at the People’s Choice Awards. It was also nominated for best Film, Director, Actor (Richard Dreyfuss), Editing, and Sound at the 29th British Academy Film Awards, and Best Film—Drama, Director, and Screenplay at the 33rd Golden Globe Awards. Spielberg was nominated by the Directors Guild of America for a DGA Award, and the Writers Guild of America nominated Peter Benchley and Carl Gottlieb’s script for Best Adapted Drama.

In the years since its release, Jaws has frequently been cited by film critics and industry professionals as one of the greatest movies of all time. It was number 48 on American Film Institute’s 100 Years. 100 Movies, a list of the greatest American films of all time compiled in 1998; it dropped to number 56 on the 10 Year Anniversary list. AFI also ranked the shark at number 18 on its list of the 50 Best Villains, Roy Scheider’s line «You’re gonna need a bigger boat» 35th on a list of top 100 movie quotes, Williams’s score at sixth on a list of 100 Years of Film Scores, and the film as second on a list of 100 most thrilling films, behind only Psycho. In 2003, The New York Times included the film on its list of the best 1,000 movies ever made. The following year, Jaws placed at the top of the Bravo network’s five-hour miniseries The 100 Scariest Movie Moments. The Chicago Film Critics Association named it the sixth scariest film ever made in 2006. In 2008, Jaws was ranked the fifth greatest film in history by Empire magazine, which also placed Quint at number 50 on its list of the 100 Greatest Movie Characters of All Time. The film has been cited in many other lists of 50 and 100 greatest films, including ones compiled by Leonard Maltin, Entertainment Weekly, Film4, Rolling Stone, Total Film, TV Guide, and Vanity Fair.

In 2001, the United States Library of Congress selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry as a «culturally significant» motion picture. In 2006, its screenplay was ranked the 63rd best of all time by the Writers Guild of America. In 2012, the Motion Picture Editors Guild listed the film as the eighth best-edited film of all time based on a survey of its membership.

Legacy [ ]

Jaws also played a major part in establishing summer as the prime season for the release of studios’ biggest box-office contenders, their intended blockbusters; winter had long been the time when most hoped-for hits were distributed, while summer was largely reserved for dumping films thought likely to be poor performers. Jaws and Star Wars are regarded as marking the beginning of the new U.S. film industry business model dominated by «high-concept» pictures—with premises that can be easily described and marketed—as well as the beginning of the end of the New Hollywood period, which saw auteur films increasingly disregarded in favor of profitable big-budget pictures. The New Hollywood era was defined by the relative autonomy filmmakers were able to attain within the major studio system; in Biskind’s description, «Spielberg was the Trojan horse through which the studios began to reassert their power.»

The film had broader cultural repercussions, as well. Similar to the way the pivotal scene in 1960’s Psycho made showers a new source of anxiety, Jaws led many viewers to fear going into the ocean. Reduced beach attendance in 1975 was attributed to it, as well as an increased number of reported shark sightings. It is still seen as responsible for perpetuating negative stereotypes about sharks and their behavior, and for producing the so-called «Jaws effect», which allegedly inspired «legions of fishermen [who] piled into boats and killed thousands of the ocean predators in shark-fishing tournaments.» Benchley stated that he would not have written the original novel had he known what sharks are really like in the wild. Indeed, Benchley himself went on to become a staunch advocate for the conservation of both sharks and the oceans as a whole, spreading his love for the seas to his family as an additional result. Conservation groups have bemoaned the fact that the film has made it considerably harder to convince the public that sharks should be protected.

Jaws set the template for many subsequent horror films, to the extent that the script for Ridley Scott’s 1979 science fiction film Alien was pitched to studio executives as «Jaws in space». Scott would later reveal in a 2017 interview that Jaws had made a lasting impression, “I was always put off from swimming ever since I watched Jaws,” says Scott. “I quite liked swimming, actually, and I’d occasionally dive, but once I saw Jaws there was no way I was ever going to learn to surf – no way! Because I can imagine my legs, my little pinkies hanging underneath the surfboard and I know I’m going to be the one.”

Many films based on man-eating animals, usually aquatic, were released through the 1970s and 1980s, such as Orca, Grizzly, Mako: The Jaws of Death, Barracuda, Alligator, Day of the Animals, Tintorera, Eaten Alive, and the 1996 Bollywood film Aatank. Spielberg declared Piranha, directed by Joe Dante and written by John Sayles, «the best of the Jaws ripoffs». Among the various foreign mockbusters based on Jaws, three came from Italy: Great White, which inspired a plagiarism lawsuit by Universal and was even marketed in some countries as a part of the Jaws franchise; Monster Shark, featured in Mystery Science Theater 3000 under the title Devil Fish; and Deep Blood, that blends in a supernatural element. The 1995 thriller film Cruel Jaws even has the alternate title Jaws 5: Cruel Jaws, and the 2009 Japanese horror film Psycho Shark was released in the United States as Jaws in Japan.

Martha’s Vineyard celebrated the film’s 30th anniversary in 2005 with a «JawsFest» festival, which had a second edition in 2012. An independent group of fans produced the feature-length documentary The Shark is Still Working, featuring interviews with the film’s cast and crew. Narrated by Roy Scheider and dedicated to Peter Benchley, who died in 2006, it debuted at the 2009 Los Angeles United Film Festival.

Home video releases [ ]

The first ever LaserDisc title marketed in North America was the MCA DiscoVision release of Jaws in 1978. A second LaserDisc was released in 1992, before a third and final version came out under MCA/Universal Home Video’s Signature Collection imprint in 1995. This release was an elaborate boxset that included deleted scenes and outtakes, a new two-hour documentary on the making of the film directed and produced by Laurent Bouzereau, a copy of the novel Jaws, and a CD of John Williams’s soundtrack.

MCA Home Video first released Jaws on VHS in 1980. For the film’s 20th anniversary in 1995, MCA Universal Home Video issued a new Collector’s Edition tape featuring a making-of retrospective. This release sold 800,000 units in North America. Another, final VHS release, marking the film’s 25th anniversary in 2000, came with a companion tape containing a documentary, deleted scenes, outtakes, and a trailer.

Jaws was first released on DVD in 2000 for the film’s 25th anniversary, accompanied by a massive publicity campaign. It featured a 50-minute documentary on the making of the film (an edited version of the one featured on the 1995 LaserDisc release), with interviews with Spielberg, Scheider, Dreyfuss, Benchley, and other cast and crew members. Other extras included deleted scenes, outtakes, trailers, production photos, and storyboards. The DVD shipped one million copies in just one month. In June 2005, a 30th-anniversary edition was released at the JawsFest festival in Martha’s Vineyard. The new DVD had many extras seen in previous home video releases, including the full two-hour Bouzereau documentary, and a previously unavailable interview with Spielberg conducted on the set of Jaws in 1974. On the second JawsFest in August 2012, the Blu-ray Disc of Jaws was released, with over four hours of extras, including The Shark Is Still Working. The Blu-ray release was part of the celebrations of Universal’s 100th anniversary, and debuted at fourth place in the charts, with over 362,000 units sold.

Sequels [ ]

Jaws spawned three sequels, none of which approached the success of the original. Their combined domestic grosses amount to barely half of the first film’s. In October 1975, Spielberg declared to a film festival audience that «making a sequel to anything is just a cheap carny trick». Nonetheless, he did consider taking on the first sequel when its original director, John D. Hancock, was fired a few days into the shoot; ultimately, his obligations to Close Encounters of the Third Kind, which he was working on with Dreyfuss, made it impossible. Jaws 2 (1978) was eventually directed by Jeannot Szwarc; Scheider, Gary, Hamilton, and Jeffrey Kramer all reprised their roles. It is generally regarded as the best of the sequels. The next film, Jaws 3-D (1983), was directed by Joe Alves, who had served as art director and production designer, respectively, on the two preceding films. Starring Dennis Quaid and Louis Gossett, Jr., it was released in the 3-D format, although the effect did not transfer to television or home video, where it was renamed Jaws 3. Jaws: The Revenge (1987), directed by Joseph Sargent, starring Michael Caine, and featuring the return of Gary, is considered one of the worst movies ever made. While all three sequels made a profit at the box office (Jaws 2 and Jaws 3-D were among the top 20 highest-grossing films of their respective years), critics and audiences alike were generally dissatisfied with the films.

Adaptations and merchandise [ ]

The film has inspired two theme park rides: one at Universal Studios Florida, which closed in January 2012, and one at Universal Studios Japan. There is also an animatronic version of a scene from the film on the Studio Tour at Universal Studios Hollywood. There have been at least two musical adaptations: JAWS The Musical!, which premiered in 2004 at the Minnesota Fringe Festival, and Giant Killer Shark: The Musical, which premiered in 2006 at the Toronto Fringe Festival. Three video games based on the film were released: 1987’s Jaws, developed by LJN for the Nintendo Entertainment System; 2006’s Jaws Unleashed by Majesco Entertainment for the Xbox, PlayStation 2, and PC; and 2011’s Jaws: Ultimate Predator, also by Majesco, for the Nintendo 3DS and Wii. A mobile game was released in 2010 for the iPhone. Aristocrat made an officially licensed slot machine based on the movie.

Movie Trivia Questions And Answers

If you think you’re a film buff, then test out your knowledge with these free movie trivia questions and answers. Why not get together with your friends and family to see who comes out on top?

The answers are at the bottom of the page. Who will be leading man or lady of movie trivia?

Fun Movie Trivia Questions

1. Which war movie won the Academy Award for Best Picture in 2009?

The Hurt Locker.

2. What was the name of the second Indiana Jones movie, released in 1984?

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.

3. Which actor starred in the 1961 movie The Hustler?

4. In which year were the Academy Awards, or “Oscars”, first presented?

5. “After all, tomorrow is another day!” is the last line from which movie that won the Academy Award for Best Picture in 1939?

Gone with the Wind.

6. Which movie features Bruce Willis as John McClane, a New York police officer, taking on a gang of criminals in a Los Angeles skyscraper on Christmas Eve?

7. What is the name of the hobbit played by Elijah Wood in the Lord of the Rings movies?

8. Which actress plays Katniss Everdeen in the Hunger Games movies?

9. Judy Garland starred as Dorothy Gale in which classic movie?

The Wizard of Oz.

10. What is the name of the kingdom where the 2013 animated movie Frozen is set?

11. Which 1997 science fiction movie starring Will Smith and Tommy Lee Jones tells the story of a secret agency that polices alien refugees who are living on earth disguised as humans?

12. Which English actor won the 2014 Academy Award for best actor for his role in The Theory of Everything?

13. In which 1984 science fiction movie did Linda Hamilton play the role of Sarah Connor?

14. Which classic thriller movie stars Roy Schieder as the police chief Martin Brody?

15. Which 1952 musical comedy tells the story of three performers making the transition from silent movies to “talkies”?

Singin’ in the Rain.

16. Which English director was responsible for the epic movie Gladiator in 2000?

17. In which movie did Julia Roberts play a kind-hearted prostitute called Vivian Ward?

18. Who played Jack Dawson in the 1997 epic Titanic?

19. Which Tom Hanks movie won the Academy Award for Best Picture in 1994?

20. Who directed the epic historical drama Schindler’s List in 1993?

21. Who was the first African American actor to win the Academy Award for Best Actor?

Sidney Poitier for his role in Lilies of the Field in 1963.

Тесты ЕГЭ по английскому языку. № 3-6.

Прочитайте текст и выполните задания A15-A21, вставив цифру 1, 2, 3 или 4, соответствующую номеру выбранного вами варианта ответа.

AT THE POLICE STATION

Signora Grismondi and Lieutenant Scarpa sat opposite one another for some time, until finally Scarpa pushed himself out of his chair, came around behind hers, and left the room, careful to leave the door open behind him. Signora Grismondi sat and studied the objects on the lieutenant’s desk, but she saw little to reflect the sort of man she was dealing with: two metal trays that held papers, a single pen and a telephone.

The room had only a small window, and it was closed, so after twenty minutes Signora Grismondi could no longer ignore how uncomfortable she felt, even with the door open behind her. It had grown unpleasantly warm, and she got to her feet, hoping it might be cooler in the corridor. At the moment she stood, however, Lieutenant Scarpa came back into the room, a manila folder in his right hand. He saw her standing and said, ‘You weren’t thinking of leaving, were you, Signora‘?’

There was no audible menace in what he said, but Signora Grismondi, her arms falling to her sides, sat down again and said, ‘No, not at all.’ In fact, that was just what she wanted to do, leave and have done with this, let them work it out for themselves.

Scarpa went back to his chair, took his seat, glanced at the papers in the trays as if searching for some sign that she had looked through them while he was away, and said, ‘You’ve had time to think about this, Signora. Do you still maintain that you gave money to this woman and took her to the train station?’

Though the lieutenant was never to know this, it was this flash of sneering insinuation that stiffened Signora Grismondi`s resolve. ‘I am not «maintaining” anything, Lieutenant,’ she said with studied calm. ‘I am stating, declaring, asserting, proclaiming, and, if you will give me the opportunity to do so, swearing, that the Romanian woman whom I knew as Flori was locked out of the home of Signora Battestini and that Signora Battestini was alive and standing at the window when I met Flori on the street. Further, I state that, little more than an hour later, when I took her to the station, she seemed calm and untroubled and gave no sign that she had the intention of murdering anyone.’ She wanted to continue, to make it clear to this savage that there was no way that Flori could have committed this crime. Her heart pounded with the desire to continue telling him how wrong he was, but the habit of civilian caution exerted itself and she stopped speaking.

Scarpa, impassive, got up and, taking the folder with him, left the room again. Signora Grismondi sat back in her chair and tried to relax, told herself that she had had her say and it was finished. She forced herself to take deep breaths, then leaned back in the chair and closed her eyes.

After long minutes she heard a sound behind her, opened her eyes and turned towards the door. A man as tall as Scarpa, though not dressed in uniform, stood there, holding what looked to be the same manila envelope. He nodded when her eyes met his and gave a half-smile. ‘If you’d be more comfortable, Signora, we can go up to my office. It has two windows, so I imagine it will be a little cooler.’ He stepped aside, thus inviting her to approach.

She stood and walked to the door. ‘And the lieutenant?’ she asked.

‘He won’t trouble us there,’ he said and put out his hand. ‘I’m Commissario Guido Brunetti. Signora, and I’m very interested in what you have to tell us.`

She studied his face, decided that he was telling the truth when he said that he was interested in what she had to say, and took his hand. After this formal moment, he waved her through the door.

A15 Signora Grismondi looked at the objects on Scarpa’s desk because she

l) felt that he wanted her to do so.

2) thought they might give her an idea of his personality.

3) wanted to keep her mind occupied.

4) expected to find something unusual about them.

A16 When Scarpa returned to the room,

l) he spoke to Signora Grismondi with an aggressive tone of voice.

2) Signora Grismondi felt that she had to remain in the room.

3) Signora Grismondi was about to try to leave the building.

4) he didn’t notice at first that she was standing up.

A17 When Scarpa sat down and asked his question, Signora Grismondi

l) spoke to him in an angry way about his attitude towards her.

2) wondered whether she should change the story she had told him.

3) was annoyed that he was suggesting that she hadn’t told the truth.

4) told him that she did not understand his use of the word ‘maintain’.

A18 Signora Grismondi`s account of what happened included

l) Flori’s denial of involvement in the crime.

2) the reason why she took Flori to the station.

3) her personal impression of Flori’s state of mind.

4) an acceptance that she might not have seen everything.

A19 Signora Grismondi did not continue speaking to Scarpa because she felt that

l) he did not want to hear any more details.

2) it was wrong for her to criticise a policeman.

3) he was incapable of understanding her point of view.

4) she was beginning to make him angry.

A20 When Scarpa left the room again, Signora Grismondi

l) was worried by his behaviour as he left.

2) accepted that she would have to remain there for some time.

3) wished that she had said more.

4) had some difficulty in calming down.

A21 When Commissario Brunetti spoke to Signora Grismondi,

1) he implied that he was not in agreement with Scarpa.

2) he expressed surprise at conditions in the room.

3) she found his behaviour strange in the circumstances.

4) she feared that he was not being honest with her.