What were the confederate states

What were the confederate states

Confederate States of America

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

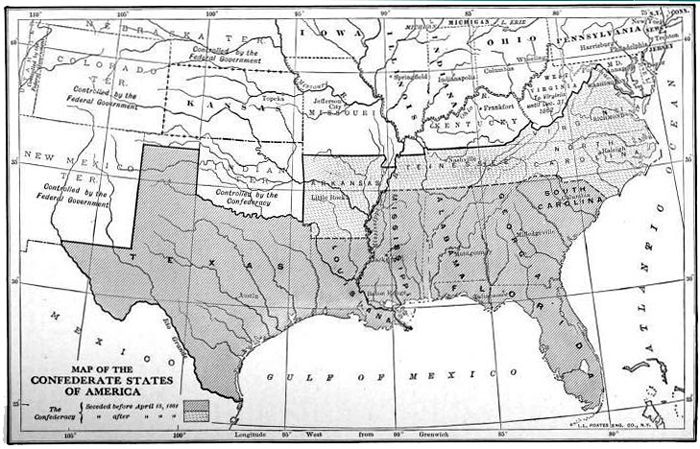

Confederate States of America, also called Confederacy, in the American Civil War, the government of 11 Southern states that seceded from the Union in 1860–61, carrying on all the affairs of a separate government and conducting a major war until defeated in the spring of 1865.

The road to secession

In the decades prior to 1860 there had been developing a steadily increasing bitterness between the Northern and Southern sections of the United States. These disputes gave rise to a fundamental disagreement about the rights of individual states and sparked diverging views about the meaning of important parts of the Constitution. While many economic, social, and political factors would feed into this regional antagonism, the central issue dividing the North and the South was slavery.

From the establishment of the American colonies in the 17th century, the labour of enslaved people had been a key factor in the economic growth of the English settlements. Enslaved people first were brought to Virginia in 1619, and the region would be transformed by cash crops, such as cotton, sugar, and tobacco, as well as the “peculiar institution” that made possible the agricultural economy of the South. During the reign of “ King Cotton” (the early to mid-1800s) about one-third of the Southern population consisted of enslaved Black people. Although agriculture remained a significant part of the economy of the North, the Northern industrial and commercial sectors were far more developed than those of the South. After the American Revolution the North had largely given up slavery as uneconomical, although it still took several decades for many states to formally abolish the practice.

In February 1819 the country’s diverging views on slavery reached a critical juncture. Congress was debating a bill that would enable the territory of Missouri to craft a state constitution when Rep. James Tallmadge of New York introduced an amendment that would prohibit the further introduction of enslaved people into Missouri and emancipate all enslaved people already there when they reached age 25. The Tallmadge amendment was approved by the House of Representatives, where the populous North had a majority, but it was rejected in the Senate, where there was an even balance of free and slave states. The deadlock between the two houses lasted more than a year, during which time the nature of slavery was thoroughly debated. Finally, in March 1820, Speaker of the House Henry Clay secured passage of an acceptable compromise. The District of Maine was separated from Massachusetts and permitted to enter the Union as a free state, Missouri was admitted as a slave state, and slavery was excluded from the rest of the Louisiana Purchase north of latitude 36°30′. This kept the balance between free and slave states at 12 each.

The Missouri Compromise temporarily postponed a final reckoning over slavery, but the long rancorous debate left its mark upon the South. Southerners had heard slavery roundly denounced on the floor of Congress as morally wrong, and Northern domination of the House of Representatives revealed to Southerners their status as a political minority. The South became increasingly preoccupied with the need to defend its social and economic institutions by preserving an equal balance of free and slave states in the Senate. While the North sought to prevent the spread of slavery into the territories, the South declared that its citizens had a constitutional right to take enslaved people there. Of the seeming stalemate produced by the Missouri Compromise, U.S. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams observed, “Take it for granted that the present is a mere preamble—a title page to a great, tragic volume.”

Over the next four decades, sectional tension would continue to grow in spite of a series of “compromises” that attempted to balance the demands of the North and the South. In August 1846, shortly after the outbreak of the Mexican-American War, Pennsylvania Rep. David Wilmot offered an amendment to a routine appropriation bill that would bar slavery from any territory gained as a result of that conflict. The effect of the Wilmot Proviso was to centre antislavery thought on the issue of “free soil.” Ignoring slavery where it was already established, the call for “free soil” sought only to prevent its expansion into the territories of the West. Abolitionism had not yet achieved widespread popular support, because its demand for immediate uncompensated emancipation was too radical for many property-conscious Americans. However, “free soil,” the lowest common denominator of antislavery feeling, had broad popular appeal. Passed by the House and rejected by the Senate in three successive years, the Wilmot Proviso would spur the creation of the short-lived but influential Free-Soil Party.

With the end of the Mexican-American War and the conclusion of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, more than 525,000 square miles (1,360,000 square km) of land (now Arizona, California, western Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah) was acquired from Mexico. Slavery immediately became the key issue at the centre of any discussion of the new territory, and the proposed statehood of California spurred Southern politicians to action. In the spring of 1849 Sen. John C. Calhoun of South Carolina issued a “Southern Address,” calling for Southern states to unite in opposition to the Wilmot Proviso. Calhoun then urged Mississippi to call a sectional convention to meet and discuss the problems of the South. Delegates from nine Southern states met in Jackson, Mississippi, in October 1849, and the attendees agreed that another convention would need to be held to include all the slaveholding states. In 1850 a pair of meetings that came to be known as the Nashville Convention were held in Tennessee. The second session concluded with representatives discussing the possibility of secession from the Union.

At this juncture Henry Clay intervened with his last great compromise. On January 29, 1850, Clay introduced an omnibus bill designed to settle all the outstanding issues that divided the nation. California would be admitted as a free state, and a more aggressive fugitive slave law would be forwarded to placate the South. New Mexico and Utah would obtain territorial governments with popular sovereignty, enabling citizens to decide for themselves the slavery issue. The bill also compensated Texas for the loss of New Mexico and prohibited the slave trade (but not slavery) in the District of Columbia.

Clay, who had devoted his four-decade political career to the defense of the Union, died in 1852, so he would not live to see the rapid unspooling of his life’s work. The Missouri Compromise was repealed by the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854), which allowed for the expansion of slavery into the western territories under the banner of popular sovereignty. Rather than calming tensions, the Kansas-Nebraska Act served only to inflame them. Bands of proslavery and antislavery advocates descended on the territory, plunging it into a localized civil war that the press dubbed “Bleeding Kansas.” What remained of Clay’s legacy was undone by the Dred Scott decision of 1857. In that case the U.S. Supreme Court ruled (7–2) that Dred Scott, an enslaved person, was not entitled to his freedom by virtue of having resided in a free state and territory (where slavery was prohibited) and, additionally, that African Americans were not and could never be citizens of the United States. The ruling, widely considered the worst decision in the history of the Court, also declared the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional and voided the legitimacy of the doctrine of popular sovereignty. The North exploded at the decision, and Northern jurists and governments effectively rejected a ruling by the country’s highest court as nonbinding. The Union appeared to be on the verge of disintegration.

The election of Abraham Lincoln and the secession crisis

The sectional dispute came to a head in 1860 when Abraham Lincoln was elected president. The Southern states held that both Lincoln and the Republican Party threatened their constitutional rights in the Union, their social institutions, and their economic existence. For more than a decade Southern leaders had argued that secession might be their only protection, and the time for it seemed to be at hand. South Carolina began the process by withdrawing from the Union on December 20. The movement quickly spread to Georgia and the states bordering the Gulf of Mexico, and before the end of January 1861 all of them had seceded except Texas, which withdrew on February 1.

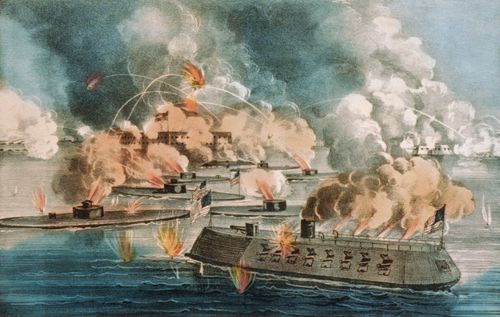

The other slave states in the Upper South and on the border were greatly agitated, but they hesitated to secede for the time. On April 12, 1861, a Southern force under Brig. Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard fired on Fort Sumter in CharlestonHarbor. Sectional tension had given way to war, and Lincoln called upon the states then in the Union for troops to enforce the laws of the land, thus initiating another wave of secession. During April and May nearly all the states of the Upper South withdrew—Virginia (April 17), Arkansas (May 6), Tennessee (May 7, although secession was not formalized until a plebiscite was held on June 8), and North Carolina (May 20). There were also strong secession movements in the border states of Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri. In Kentucky a meeting of delegates declared that state out of the Union, and in Missouri a fragment of the legislature passed a secession ordinance. Kentucky and Missouri were admitted to the newly established Confederate States of America (bringing the total of breakaway states to 13, a number that evoked the original British colonies), but the action of both states was irregular. The other 11 states that constituted the Confederacy had all been carried out of the Union by conventions elected by the people—except Tennessee, where the full legislature acted. All except Tennessee had asserted their constitutional right to secede. Tennessee based its withdrawal on the right of revolution.

Organization of the Confederate government

For many years, some Southerners had dreamed of a distinct Southern polity, and, with six states in secession, they decided to bind these states into a new country. It was necessary to make haste without waiting for the Upper South to follow, as Lincoln would be inaugurated on March 4, 1861, and it was feared that he might take action against the rebelling states immediately. So it was arranged for delegates from these six states (to be joined later by those from Texas) to meet in Montgomery, Alabama, on February 4. This convention, presided over by Howell Cobb of Georgia, immediately began to frame a document setting up the new government. Four days later it unanimously adopted the provisional constitution of the Confederate States of America, which was to serve until a permanent constitution could be written.

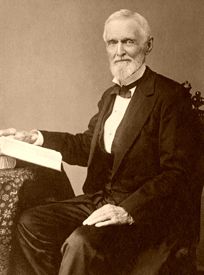

This document was rudimentary, and its chief purpose was to provide the framework of a central government. It called for a president and a vice president, to be elected by the states (each state having one vote); a supreme court composed of the district judges; a unicameral congress (with the existing convention to continue as that body); the capital to be at Montgomery until the congress should change it; and the government thus established to continue for only one year. The leaders were anxious that there should appear to be no factions in this convention. After various conferences they chose Jefferson Davis of Mississippi as president and Alexander H. Stephens of Georgia as vice president. Davis, who was not a member of the convention and who had no desire for the presidency, set out immediately from his Mississippi home. He was inaugurated on February 18 after a grand procession, which included a band playing “Dixie,” marched up the hill to the Alabama State Capitol.

In selecting his cabinet, Davis was careful to see that all seven states (except Mississippi, which held the presidency) were recognized. Christopher Memminger of South Carolina became secretary of the treasury; Robert Toombs of Georgia, secretary of state; Stephen Mallory of Florida, secretary of the navy; Leroy Walker of Alabama, secretary of war; Judah Benjamin of Louisiana, attorney general; and John Reagan of Texas, postmaster general. During the four years of the Confederacy, there were various changes in the personnel of the cabinet, but three individuals served throughout the whole period: Benjamin, one of the sharpest minds in the Confederacy, was first transferred to the war department and finally to the state department; Mallory, who was bitterly criticized during the war and for years afterward but came to be recognized as an able administrator, continued in the navy department; and Reagan, a staunch supporter of Davis, administered the post office throughout the war. Davis was probably the best selection the Confederates could have made—despite the fact that he was ill much of the time, had the use of only one eye, and seemed to lack that warmth of character and approach which would have made him much more popular. Stephens was soon to become an outspoken critic of Davis and of many Confederate policies.

The Constitution of the Confederate States of America

The convention, which was the congress under the provisional constitution—when not busy providing for the needs of the new government—turned its attention to framing a permanent constitution. On March 11 its work was completed when it adopted the document by a unanimous vote. The proposed constitution was then submitted to the states that had seceded, and all of them ratified it. This constitution throughout its framework was a modified copy of the Constitution of the United States, for the Southerners had time and again insisted that they had no quarrel with that document. Their objection was to the way the North was interpreting it. There were, however, significant additions, changes, and clarifications. A bicameral Congress of the Confederate States would be established, consisting of a Senate and a House of Representatives. The president was to serve for a term of six years and be ineligible for reelection; the president might veto separate items in appropriation bills. With the consent of Congress, cabinet members might have seats on the floor of either house; a budget system was adopted, and Congress was not authorized to increase items in a budget except by a two-thirds majority; after the first two years, the post office department was required to be self-sustaining; foreign slave trade was prohibited; and no law could relate to more than one subject. By way of clarification, Congress was forbidden to foster any industry by a protective tariff, appropriate money for internal improvements, or limit the right to take enslaved people into a territory. Although there was a provision for a supreme court, Congress never set one up, largely through fear of the power it might assume.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, one striking difference between the U.S. and Confederate constitutions was the latter’s overt enshrinement of the institution of slavery. Neither the word slave nor the word slavery appears in the unamended U.S. Constitution. Even the three-fifths compromise (Article 1, Section 2), which allowed Southern states to count three-fifths of their enslaved populations for the purposes of apportionment of seats in the House of Representatives, euphemistically referred to enslaved people as “other Persons.” The Confederate constitution retained the three-fifths compromise for matters of taxation and representation but removed any doubt about its subject by applying it to “three-fifths of all slaves.”

Elsewhere in the Confederate constitution, slavery was established as an immutable aspect of the Confederate state. Article I, Section 9, declared, “No bill of attainder, ex post facto law, or law denying or impairing the right of property in negro slaves, shall be passed.” On the matter of the possible expansion of the Confederacy into new territory, Article IV, Section 3, noted, “In all such territory, the institution of negro slavery as it now exists in the Confederate States, shall be recognized and protected by Congress, and by the territorial government; and the inhabitants of the several Confederate States and Territories, shall have the right to take to such territory any slaves, lawfully held by them in any of the States or Territories of the Confederate States.”

On March 21, 10 days after the adoption of the Confederate constitution, Stephens delivered an address in which he attempted to explain the goals of the Confederacy and the significance of “one of the greatest revolutions in the annals of the world.” In his “Cornerstone Speech,” the vice president of the Confederacy stated, “The new constitution has put at rest, forever, all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution—African slavery as it exists amongst us—the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization” He rejected the notion of “equality of races” and proclaimed:

“Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.”

The Confederacy would be, at its core, a government firmly rooted in notions of white supremacy.

Confederate States of America

Contents

The Confederate States of America was a collection of 11 states that seceded from the United States in 1860 following the election of President Abraham Lincoln. Led by Jefferson Davis and existing from 1861 to 1865, the Confederacy struggled for legitimacy and was never recognized as a sovereign nation. After suffering a crushing defeat in the Civil War, the Confederate States of America ceased to exist.

NORTH VERSUS SOUTH

The southern and northern United States began to pull apart in the 19th century, culturally and economically, with slavery at the center of the rift. As early as 1850, South Carolina and Mississippi called for secession.

By 1860, Southern politics was dominated by the idea of states’ rights in the context of slavery to support the South’s agricultural economy, and slave-heavy, cotton-producing agricultural states embraced secession as the solution.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN

The election of Abraham Lincoln was labeled an act of war by some Southern politicians, who predicted armies would come to seize slaves and force white women to marry black men. Secession meetings and assemblies started to appear across the South.

As secession began to seem more likely, so did war. Altercations with Union troops at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, and Fort Pickens, Florida, escalated.

Southern politicians began to procure weaponry, and some secessionists even proposed kidnapping Lincoln.

SECESSION

By February 1861, seven Southern states had seceded. On February 4 of that year, representatives from South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia and Louisiana met in Montgomery, Alabama, with representatives from Texas arriving later, to form the Confederate States of America.

Former secretary of war, military man and then-Mississippi Senator Jefferson Davis was elected Confederate president. Ex-Georgia governor, congressman and former anti-secessionist Alexander H. Stephens became vice-president of the Confederate States of America.

CONFEDERATE CONSTITUTION

The Confederacy used the U.S. Constitution as a model for its own, with some wording differences and a few changes regarding the executive and judicial branches.

The Confederate president would serve for six years with no reelection possibility, but was considered more powerful than his Union counterpart.

While the Confederate Constitution upheld the institution of slavery, it prohibited the African slave trade.

CONFEDERATE ENLISTMENT

Davis predicted a long war and requested legislation allowing three-year enlistments. The military affairs office, however, anticipated a short conflict and granted the authority to call up troops for only one year of service.

On March 9, 1861, Davis called up 7,700 volunteers from five states, joining volunteers in South Carolina. By mid-April, 62,000 troops were raised and stationed in former Union bases.

CIVIL WAR BEGINS

On April 12, 1861, following diplomatic bickering over Lincoln’s pledge to get supplies to Union troops at Fort Sumter, Confederate forces fired shots at the fort and Union troops surrendered, sparking the Civil War.

In rapid succession, Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Arkansas joined the Confederacy.

In May, Davis made Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital. The city was soon filled with some 1,000 government members, 7,000 civil servants, and scores of rowdy Confederate soldiers itching for battle.

The First Battle of Bull Run took place on July 16, 1861, and ended with a Confederate victory.

CONFEDERATE ARIZONA

The Arizona Territory voted to join the Confederacy in March 1861, but it wasn’t until 1862 that the territorial government got around to officially proclaiming it part of the Confederate States of America.

Several battles took place within the territory, and in 1863, Confederate forces were vanquished from the Arizona Territory, which was claimed as Union and then split into two territories, the second being the New Mexico Territory.

MARTIAL LAW AND MANDATORY SERVICE

Most of the work of the Confederate government involved trying to wage the Civil War without the appropriate means, a domino effect that sometimes rendered it helpless.

In February 1862, Davis was granted the authority to suspend habeas corpus, which he did immediately until July 1864, and to declare martial law, which Davis did many times during the war.

Recommended for you

The Origins of 7 Popular Sports

8 Fascinating Facts About Ancient Roman Medicine

What Caused Ancient Egypt’s Decline?

Problems with adequately arming the troops, as well as getting supplies to them, hampered war efforts. The brief one-year enlistment also caused problems because as the war dragged on, rates of volunteering and re-enlistment fell.

Davis was soon forced to make military service mandatory for all able-bodied males between 18 and 35 years old. Later exemptions were made for owners of 20 slaves or more. Regardless, Union troops radically outnumbered the Confederate troops.

A SHORTAGE OF MEN

The draft created a deficit in civilian manpower to police the slave population. States created separate courts to try slaves because of elevated disobedience levels. Paranoia rose, and some hoped to remedy it through conscripting slaves into military service.

There was also a severe shortage of white workers. Out of need, the Confederacy employed both free and enslaved blacks at a higher rate during the war, using blacks to support the troops with services and by working in hospitals as nurses and orderlies.

CONFEDERACY IN CHAOS

State governors found themselves continually in conflict with Davis about government overreach challenging their sacred states rights, especially federal conscription laws.

The military exacerbated the situation: As the war dragged on, some troops prowled the countryside to rob civilians. Others rounded up civilians for random (often unfounded) infractions, infuriating local authorities.

The federal government reflected this chaos. Davis saw his authority repeatedly challenged, almost facing impeachment. Davis feuded regularly with Vice-President Stephens, bickered with generals, often had to reconstruct his cabinet and faced repeated backlashes from previously supportive newspapers.

FINANCIAL DISASTER

The chaos in government spread outward. The Confederacy was plagued by major economic problems throughout the war, unable to keep up with the production boom in the industrialized north and incapable of overcoming the export limitations brought on by war.

As the war neared its end, the Confederacy was crippled by severe infrastructure problems that it could not afford to fix and was desperate for supplies. With banks decimated and closing, it attempted to pay for its needs with IOUs.

CONFEDERATE LOSSES

Despite further conscription efforts, Confederate forces dwindled to about one-third the manpower of their Union foes. Davis faced opposition in Congress and attempted to save his position by restructuring military leadership.

Militarily, the Confederacy saw considerable losses on the battlefields, and Atlanta and Chattanooga were taken by Union forces, which continued to advance.

Increasing numbers of Confederate soldiers were deserting and returning home. The Conscript Bureau was closed in 1865, no longer able to find men to draft.

ARMING THE SLAVES

The concept of drafting and arming slaves was a recurring issue throughout the Confederacy’s existence, and it almost became a reality just before the fall of the rebel nation.

In the final session of Congress in 1865, Davis proposed the federal government purchase 40,000 slaves for military work followed with some form of emancipation. In March, Congress voted to arm slaves, but offered no emancipation.

General Order 14 resulted, which would immediately give freedom to slaves who served in the military. Recruiting and training black soldiers began.

Some members of Congress, however, began to make amends with the Union. Resignations began to pile up in the president’s cabinet.

Three weeks later, Richmond fell, and Davis fled to North Carolina.

CONFEDERATE STATES OF AMERICA COLLAPSES

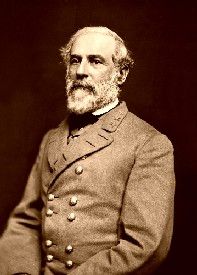

On April 9, Confederate General Robert E. Lee and his famed Army of Northern Virginia surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant.

Despite Davis’ order for a new phase of war shifting to guerrilla tactics, many troops followed Lee and also surrendered.

By May, Confederate officials announced the government had ended. Davis refused to give up hope, but was captured by Union forces in Georgia in May 1865, and sent to prison for two years. He never backed down on his devotion to the Confederate cause.

The Civil War officially ended on May 13, 1865, and the Confederate States of America ceased to exist.

SOURCES

Look Away: A History of the Confederate States of America. William C. Davis.

The Confederate Nation: 1861 to 1865. Emory M. Thomas.

The Civil War. National Parks Service.

Confederate States (Differently)

Timeline: Differently

.svg) |  |

| Flag | Seal |

Deo Vindice (Latin)

«Under God, our Vindicator»

«Dixie»

883,325 sq mi

The Confederate States of America (CSA; Spanish: Estados Confederados de América; French: États Confédérés d’Amérique), commonly known as the Confederate States, the Confederacy, or by its nickname, «Dixie«, is a country in North America. It borders the United States to the north and west, Mexico to the southwest and is bounded by the Atlantic Ocean on the east and by the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea on the south. It also shares maritime borders with the Bahamas, Jamaica, and Haiti.

At 883,325 sq mi (or 2,287,800 km²), it is the sixth-largest country in the Americas and the 16th-largest in the world. With over 114 million inhabitants distributed through its fourteen states, the Confederacy is the world’s 15th-most populous country, ranking fourth in the Americas. The capital is Richmond, Virginia and the largest city is Houston, Texas. Other large cities include San Antonio, Dallas, Austin, Miami, and Jacksonville.

Although no language is official at the federal level, English is the most predominantly spoken, followed by Spanish. Indigenous languages are also present in the nation and have been historically important.

The nation is known for its distinguishable customs, musical styles, and cuisine. It is also a racially diverse country populated by European, African, Hispanic, and Native American ethnic groups.

The Confederacy is a member of the League of Nations and the BRIC.

Contents

History

Pre-colonization

A Mississipian priest

The first well-dated evidence of human occupation in the region occurs around 9500 BC with the appearance of the earliest documented Americans, who are now referred to as Paleo-Indians. Paleoindians were hunter-gathers that roamed in bands and frequently hunted megafauna. Several cultural stages, such as Archaic (ca. 8000–1000 BC) and the Woodland (ca. 1000 BC – AD 1000), preceded what the Europeans found at the end of the 15th century — the Mississippian culture.

The Mississippian culture was a complex, mound-building Native American culture that flourished in what is now the Confederate States from approximately 800 AD to 1500 AD. Natives had elaborate and lengthy trading routes connecting their main residential and ceremonial centers extending through the river valleys and from the East Coast to the Great Lakes. Some noted explorers who encountered and described the Mississippian culture, by then in decline, included Pánfilo de Narváez (1528), Hernando de Soto (1540), and Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville (1699).

Native American descendants of the mound-builders include Alabama, Apalachee, Caddo, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, Guale, Hitchiti, Houma, and Seminole peoples, all of whom still reside in the South. Other peoples whose ancestral links to the Mississippian culture are less clear but were clearly in the region before the European incursion include the Catawba and the Powhatan. Although the Mississippians were also influenced by the descendants of the Vinlanders, who introduced runes and horseback riding to North America in the 11th century, these technologies were never fully incorporated into Mississippian culture.

Colonial period

Benjamin Hawkins, seen here on his plantation, teaching Creek Native Americans how to use European technology

European immigration caused a die-off of Native Americans, whose immune systems could not protect them from the diseases the Europeans unwittingly introduced.

The predominant culture of the original Southern states was British. In the 17th century, most voluntary immigrants were of English origin, and settled chiefly along the eastern coast but had pushed as far inland as the Appalachian Mountains by the 18th century. The majority of early English settlers were indentured servants, who gained freedom after working off their passage. The wealthier men who paid their way received land grants known as headrights, to encourage settlement.

The Spanish and French established settlements in Florida, Texas, and Louisiana. The Spanish settled Florida in the 16th century, reaching a peak in the late 17th century, but the population was small because the Spaniards were relatively uninterested in agriculture, and Florida had no mineral resources.

In the British colonies, immigration began in 1607 and continued until the outbreak of the Revolution in 1775. Settlers cleared land, built houses and outbuildings, and on their own farms. The Southern rich owned large plantations that dominated export agriculture and used slaves. Many were involved in the labor-intensive cultivation of tobacco, the first cash crop of Virginia. Tobacco exhausted the soil quickly, requiring that farmers regularly clear new fields. They used old fields as pasture, and for crops such as corn wheat, or allowed them to grow into woodlots.

In the mid-to-late-18th century, large groups of Ulster Scots (later called the Scotch-Irish) and people from the Anglo-Scottish border region migrated and settled in the backcountry of Appalachia and the Piedmont. They were the largest group of non-English immigrants from the British Isles before the American Revolution.

The oldest university in the country, the College of William & Mary, was founded in 1693 in Virginia; it pioneered in the teaching of political economy and educated future U.S. Presidents Jefferson, Monroe and Tyler, all from Virginia.

Indeed, the entire region dominated politics in the First Party System era: for example, four of the first five Presidents — Washington, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe — were from Virginia. The two oldest public universities are also in the South: the University of North Carolina (1789) and the University of Georgia (1785).

American Revolution

The Battle of Guilford Courthouse, fought on March 15, 1781 in present-day Greensboro, North Carolina

With Virginia in the lead, the Southern colonies embraced the American Revolution, providing such leaders as commander-in-chief George Washington, and the author of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson.

In 1780 and 1781, the British largely halted reconquest of the northern states, and concentrated on the south, where they were told there was a large Loyalist population ready to leap to arms once the royal forces arrived. The British took control of Savannah and Charleston, capturing a large American army in the process, and set up a network of bases inland. There were many more Loyalists in the South than in the North, but they were concentrated in larger coastal cities and were not great enough in number to overcome the revolutionaries. Large numbers of loyalists from South Carolina fought for the British in the Battle of Camden.

The British forces at the Battle of Monck’s Corner and the Battle of Lenud’s Ferry consisted entirely of Loyalists with the exception of the commanding officer (Banastre Tarleton). Both white and black Loyalists fought for the British at the Battle of Kemp’s Landing in Virginia. Led by Nathanael Greene and other generals, the Americans engaged in Fabian tactics designed to wear down the British invasion force, and to neutralize its strong points one by one. There were numerous battles large and small, with each side claiming some victories. By 1781, however, British General Cornwallis moved north to Virginia, where an approaching army forced him to fortify and await rescue by the British Navy. The British Navy did arrive, but so did a stronger French fleet, and Cornwallis was trapped. American and French armies, led by Washington, forced Cornwallis to surrender his entire army in Yorktown, Virginia in October 1781, effectively winning the North American part of the war.

The Revolution provided a shock to slavery in the South. Thousands of slaves took advantage of wartime disruption to find their own freedom, catalyzed by the British Governor Dunmore of Virginia’s promise of freedom for service. Many others were removed by Loyalist owners and became slaves elsewhere in the Empire. Between 1770 and 1790, there was a sharp decline in the percentage of blacks – from 61% percent to 44% in South Carolina and from 45% to 36% in Georgia.

In addition, some slaveholders were inspired to free their slaves after the Revolution. They were moved by the principles of the Revolution, and Quaker and Methodist preachers worked to encourage slaveholders to free their slaves. Planters such as George Washington often freed slaves by their wills. In the upper South, more than 10 percent of all blacks were free by 1810, a significant expansion from pre-war proportions of less than 1 percent free.

Antebellum

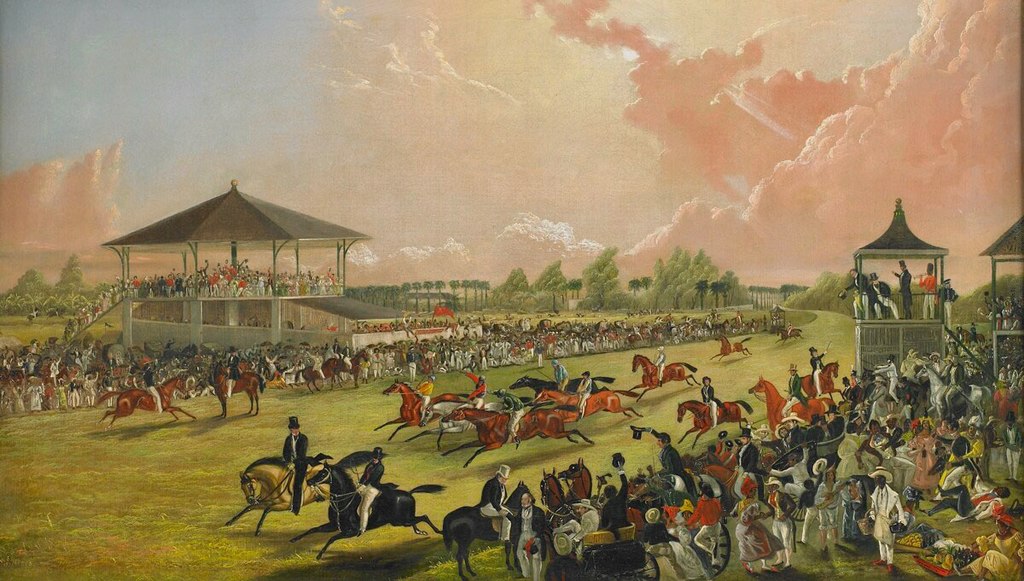

Horse racing at Jacksonville, Alabama, 1841

Cotton became dominant in the lower South after 1800. After the invention of the cotton gin, short staple cotton could be grown more widely. This led to an explosion of cotton cultivation, especially in the frontier uplands of Georgia, Alabama and other parts of the Deep South, as well as riverfront areas of the Mississippi Delta. Migrants poured into those areas in the early decades of the 19th century, when county population figures rose and fell as swells of people kept moving west. The expansion of cotton cultivation required more slave labor, and the institution became even more deeply an integral part of the South’s economy.

With the opening up of frontier lands after the government forced most Native Americans to move west of the Mississippi, there was a major migration of both whites and blacks to those territories. From the 1820s through the 1850s, more than one million enslaved Africans were transported to the Deep South in forced migration, two-thirds of them by slave traders and the others by masters who moved there. Planters in the Upper South sold slaves excess to their needs as they shifted from tobacco to mixed agriculture. Many enslaved families were broken up, as planters preferred mostly strong males for field work.

Two major political issues that festered in the first half of the 19th century caused political alignment along sectional lines, strengthened the identities of North and South as distinct regions with certain strongly opposed interests, and fed the arguments over states’ rights that culminated in secession and the War for Southern Independence. One of these issues concerned the protective tariffs enacted to assist the growth of the manufacturing sector, primarily in the North. In 1832, in resistance to federal legislation increasing tariffs, South Carolina passed an ordinance of nullification, a procedure in which a state would, in effect, repeal a Federal law. Soon a naval flotilla was sent to Charleston harbor, and the threat of landing ground troops was used to compel the collection of tariffs. A compromise was reached by which the tariffs would be gradually reduced, but the underlying argument over states’ rights continued to escalate in the following decades.

The second issue concerned slavery, primarily the question of whether slavery would be permitted in newly admitted states. The issue was initially finessed by political compromises designed to balance the number of «free» and «slave» states. The issue resurfaced in more virulent form, however, around the time of the Mexican–American War, which raised the stakes by adding new territories primarily on the Southern side of the imaginary geographic divide. Congress opposed allowing slavery in these territories.

Before the War, the number of immigrants arriving at Southern ports began to increase, although the North continued to receive the most immigrants. Hugenots were among the first settlers in Charleston, along with the largest number of Orthodox Jews outside of New York City. Numerous Irish immigrants settled in New Orleans, establishing a distinct ethnic enclave now known as the Irish Channel. Germans also went to New Orleans and its environs, resulting in a large area north of the city (along the Mississippi) becoming known as the German Coast. Still greater numbers immigrated to Texas (especially after 1848), where many bought land and were farmers. Many more German immigrants arrived in Texas after the War, where they created the brewing industry in Houston and elsewhere, became grocers in numerous cities, and also established wide areas of farming.

By 1840, New Orleans was the wealthiest city in the country and the third largest in population. The success of the city was based on the growth of international trade associated with products being shipped to and from the interior of the country down the Mississippi River. New Orleans also had the largest slave market in the country, as traders brought slaves by ship and overland to sell to planters across the Deep South. The city was a cosmopolitan port with a variety of jobs that attracted more immigrants than other areas of the South. Because of lack of investment, however, construction of railroads to span the region lagged behind the North. People relied most heavily on river traffic for getting their crops to market and for transportation.

The War of Southern Independence

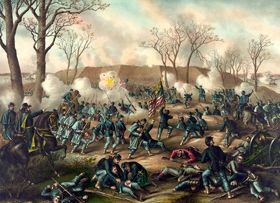

A battle between the Confederacy and the Union

The initial Confederacy was established at the Montgomery Convention in February 1861 by seven states (South Carolina, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and Louisiana, with Texas joining in March, before Lincoln’s inauguration) and expanded in May–July 1861 (with Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina). It was formed by delegations from seven states of the Lower South that had proclaimed their secession from the Union. After the fighting began in April, four additional states seceded and were admitted. Later, two states (Missouri and Kentucky) and two territories (Arizona, and the Indian Territory) were given seats in the Confederate Congress. Southern California, although having some pro-Confederate sentiment, was never organized as a territory.

Many Southern whites considered themselves more citizens of their state than of the Union and were prepared to fight for the independence of the larger nation. That regionalism became a Southern nationalism. Its first two years, the Confederacy underwent trial by war.

The first major action of the war was in July 1861 and was a Confederate victory, but the CS was unable to press the advantage.

The following spring, the Union’s Army of the Potomac, commanded by General George McClellan, was dispatched to the Virginia Peninsula to move against the CSA capital of Richmond. McClellan was hesitant, believing he was outnumbered by the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. With McClellan halting the advance, Confederate General Robert E. Lee forced the Army of the Potomac to retreat.

The following summer, Lee defeated the Union Army of Virginia under John Pope at a Second Battle of Bull Run.

In the fall of 1862, Confederate fortunes were riding extremely high, with Britain and France considering granting the CS diplomatic recognition. That fall, Lee launched an ambitious invasion of Maryland and Pennsylvania. General McClellan was slow to respond to Lee’s invasion and the Union’s intelligence failed to realize that the Army of Northern Virginia had adopted a high-risk marching order in which each division of James Longstreet’s and Thomas Jackson’s two corps were all marching alone. McClellan made the foolish decision to offer Lee battle at Camp Hill, Pennsylvania, where the Army of the Potomac was destroyed on October 1, 1862.

Lee advanced on the city of Philadelphia and took possession of it. Shortly after, Britain and France extended diplomatic recognition to the Confederate States. US President Abraham Lincoln and CS President Jefferson Davis agreed to a ceasefire on November 27, 1862. Davis recalled Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia the day after.

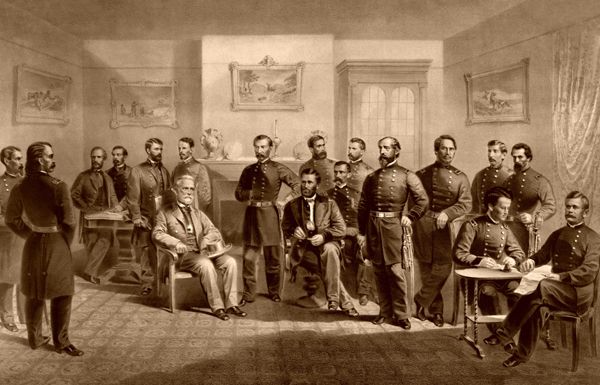

Peace negotiations began January 8, 1863 and were held in Alexandria, Virginia. British Foreign Secretary Lord Russell served as mediator between the Confederacy and the United States. Lord Russell was joined by Royal Navy Admiral Sir Sydney Colpoys Dacres, British Ambassador to the United States 1st Viscount Richard Lyons, and French Ambassador to the United States Henri Mercier. The United States was represented by President Lincoln and newly appointed US Secretary of State Elihu B. Washburne (William H. Seward had resigned from the office of Secretary of State shortly after the ceasefire), and Admiral David Farragut. The Confederacy was represented by President Jefferson Davis, CS Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin, General Robert E. Lee, and newly appointed Confederate ambassador to the United Kingdom James Murray Mason.

The key points of the treaty of Alexandria:

The treaty was signed by both presidents on February 15, 1863, ending the War for Southern Independence.

Era of Construction

Following the Treaty of Alexandria, the Confederacy’s focus turned from independence to establishing itself on the world stage. The work of Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin and Ambassador James Murray Mason would be instrumental in reestablishing the cotton trade with Britain and France, and then many other European nations. Cotton, followed by tobacco, became the Confederacy’s biggest exports.

During these years many, migrations happened between the newly establish Confederacy and the United States, creating growth in urban cities along the boarder states. To the United States came pro-Unionists, abolitionists, and even some slaves hoping to escape to freedom. To the Confederacy came opportunists who hoped to find their fortune in the young nation. Among one of these citizens was future Confederate President John Wilkes Booth, who would open Booth Theatre in Raleigh, North Carolina.

In the Appalachian Mountains, border skirmishes between the citizens of the USA states of Kentucky and Ohio and the citizens of the CSA states of Virginia and Tennessee were not uncommon throughout the 19th century. The most famed conflict was the Hatfield-McCoy feud from 1863-1891.

In the election of 1866, Vice President Alexander Stephens succeeded Jefferson Davis as President. Stephens changed the Confederacy focus from international affairs to internal affairs. Under his presidency, the Confederacy would work on establishing more railroads, and begin construction on the much needed industries that the new nation desperately lacked.

In 1867, the Confederate’s Indian Territory was turned into the state of Sequoyah to reward the five civilized tribes for their alliance with the Confederacy during the war. Unlike other states of the Confederacy, Sequoyah is controlled by the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole tribes, respectively. These tribes’ elders serve as their state government and they also appoint their own congressmen to the Confederate House of Representatives. The only elected position in the state are the two C.S. Senators.

During the latter half of Stephens’ administration, the issue of slavery became once more in the forefront of politics. Slavery had been a major factor in the start of the civil war, and the topic of abolition was seen by the majority of the public as a topic of pro-Unionists and enemies of the nation. Yet Northern support for the cause of abolitionism still had a following and in 1870 the movement in the South found an unexpected leader in war hero Thomas «Stonewall» Jackson.

Stonewall Jackson in Uniform

Before 1868, Stonewall Jackson had been an owner of six slaves and remained as far as he could to be out of politics. Yet following an assassination attempt in 1868, his entire life would change. The attempt was made by Solomon Brown in the city of Petersburg, Virginia, and was foiled by Joseph P. Evans, a black man who bought his freedom the year before the war began. Jackson, a highly religious man, took it as a sign from his Creator, and formed a quick friendship with Evens. That same year, he freed his own slaves and the following year went to the United States and met with many abolitionist leaders, including Frederick Douglass. Jackson pushed that slavery was an immoral practice and it needed to end in the Confederacy. Jackson would fall victim to much criticism at home, but his actions would spark the debate of ending slavery in the nation. Joining «Jackson’s Crusade» was fellow war hero and Ambassador James Longstreet who used more logical arguments for the ending of slavery instead of Jackson’s moral ones.

Those in favor of slave included President Stephens and many members of his administration and the congress who were wealth slave owners. Yet many of them preferred to keep away from the topic in hopes of not losing their trade partnerships with the European nations. Those who did not care about confronting Jackson and joining the debate was Senator Albert G. Brown, who had been an anti-administrationist during Davis presidency. He had joined Stephen’s supporters shortly after his election. (This was common during the early years of the Confederacy) Senator Brown saw the practice of slavery as a right with a historical and biblical precedent.

In the spring of 1871, Senator Brown and General Jackson had seven public debates against each other on the issue of slavery. They had a total of nine debates in the cities of New Orleans, Jackson, Selma, Macon, Columbia, Raleigh, Petersburg, Richmond, and finally one in Washington, D.C. These debates are now commonly known as the Jackson-Brown Debates or the Great Debates of 1871.

Another famed leader who arose from the pro-slave movement was actor John Wilkes Booth. A highly trained stage actor, Booth was able to use his name recognition to travel the nation and participate in plays. After the performances, he would give pro-slavery speeches often attacking the abolitionists by name.

The Election of 1872 would have multiple candidates but every state in the nation would be cared by Vice President Judah Benjamin. Benjamin became the first Jewish President of the Confederacy. When Benjamin was serving under Stephens, he had grown concerned of the sitting president’s focus on internal affairs instead of international affairs. This and the United States’ completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad made Benjamin believe that Europe would begin rebuilding ties with the United States.

Other than President Benjamin’s focus on keeping the Confederacy close with its European allies, he wanted to build ties with the nation of Brazil. President Benjamin, with Secretary of State John Henninger Reagan and Ambassador to Brazil William Hutchinson Norris, would establish close ties to Emperor Pedro II of Brazil, and together the two nations hoped from dual cooperation to expand their nations’ economy, industry, and influence in international affairs.

On May 17, 1875 Vice President John C. Breckinridge died at approximately 5:45 p.m. at the age of 54. He had been suffering health problems for two years before which he was forced to spend most of his vice presidency in the Virginian Mountains as he hoped the cooler conditions would improve his worsening condition. Breckinridge was the only man to serve as both Vice President to the United States (1857-1861) and to the Confederate States. (1873-1875).

Under Benjamin, the Supreme Court of the Confederacy was formed in the winter of 1875. Unlike the US Supreme Court, the Confederacy’s justices are appointed by each state’s supreme court to represent it on the national level, instead of by the president. Among the first rulings of the court was that of the issue of slavery. The court ruled that the issue of slavery was a state issue. In 1876, the Tennessee General Assembly controlled by the political alliances know as the New Americans abolished slavery, becoming the first state to do so.

In the Election of 1878, President Benjamin pressured the Pro-Administration (now known commonly as the Dixiecrats) to nominate Governor P.G.T. Beauregard. Other members of the Pro-Administation (including former President Alexander Stephens) wanted the more conservative Senator Albert G. Brown of Mississippi. Concerned that the Pro-Administration would split their vote and an anti-administration candidate (such as the popular Senator Augustus Hill Garland of Arkansas) would be able to take advantage, Benjamin nominated Secretary of State John Reagan, who was a good compromise candidate. Reagan won the presidency, yet unlike his three predecessors he was unable to take every state of the nation. Arkansas, Tennessee, and Virginia would go to the Non-Administration candidate of Senator Garland.

In hopes of making compromises with the different factions of the Pro-Administration, Reagan had picked Beauregard as his running-mate, and had appointed many members of the conservative faction into his cabinet, including Senator Brown as his Secretary of State.

President Reagan and Secretary Brown soon began to clash over the Confederacy’s position on international affairs which they often disagreed. As soon as Brown had been approved for the post of Secretary of State, he began writing up his proposal of war with Mexico. Secretary Brown hoped that a quick and divisive invasion of the poorer Southern nation would force Mexican President Porfirio Díaz to sue for peace with little opposition. The goal of the proposed war was the annexation of the Mexican states of Tamaulipas, San Luis Potosí, Nuevo León, and Coahuila. Brown hoped that with the taking of these states it would give the Confederacy a foothold in Central America. He believed that this would allow the nation to expand its interest and slavery into the region as a whole and in turn giving the CSA a hold on the sugar and tropical fruit trade into Europe and the United States.

Although Reagan saw the potential economic advantages of the invasion, he feared that such a war would lead to disapproval of their European allies and the possibility of President Blaine and the United States joining the Mexicans in the conflict. Brown would get General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate States J.E.B. Stuart to argue in favor of the war to President Reagan. Stuart felt that if the Confederacy could strike secretly, quickly and efficiently, they could force Mexico to an early peace. Yet to Brown’s disapproval, the general also expressed that he had a concern that if Mexico would learn of the attack or have a single successful victory, the United States would join them in this hypothetical war, which he stated as being an «undesirable task». After this meeting, Reagan informed Brown that the Confederacy would not enter a war with Mexico under his administration.

After this slight by his President, Secretary Brown began to work around him in hopes of getting his plans completed. In February of 1880, Secretary Brown would meet in secret with Spanish Ambassador to the Confederacy Felipe Mendes de Vigo Y Oserio, about the possible purchase of Cuba by the Confederacy, which Secretary Brown gave the price negation over to the Kingdom of Spain to handle. The Ambassador supported it, and immediately wrote to Prime Minister Antonio Cánovas del Castillo to get approval to continue the process. Many historians believe that Brown’s Deal (known commonly to day as Brown’s Folly) would have succeeded if it had not been for Ambassador Oserio telling French Ambassador Théodore Roustan about the deal following Sunday Mass. Latter that week Ambassador Roustan commented on the deal to Vice President Beauregard. (During his time in Richmond, Beauregard would often spend his evenings with the French Ambassador and his embassy staff so he could have someone he could speak with in his first language of French.) Beauregard immediately went to President Reagan, who in turn informed Brown that the Cuban deal was over and that he was ordering Brown to resign from his post as Secretary of State.

In 1879, the State Arkansas, thanks to the political alliance of the Hornets and liberal members of the Pro-Administration, abolished slavery. Two years later thanks to the behind close doors works of Vice President Beauregard Louisiana also abolish slavery.

In 1882, the Arizona Territory was given statehood, becoming the 13th state of the nation.

In the winter of 1883 as the presidential election began to get closer. President Reagan began to express his plans to choose Vice President Beauregard as is successor, against the wishes of the Pro-Slavery faction of the Dixiecrats. Many of the Conservatives of the Pro-Administration were angered by Reagan’s dismissal of Albert G. Brown from Secretary of State and refused to back the notoriously moderate Beauregard. December 3, 1883 following the start of Congressional Session, a delegation lead by Senator Laurence M. Keitt of South Carolina meet with President Reagan demanding him to nominate Senator Zebulon Baird Vance of North Carolina.

Reagan met with both Senator Vance and Vice President Beauregard hoping to find a possible compromise, but both candidates refused to step aside at the request of their president. When June came along for the annual successor meeting President Reagan tried again to work out a compromise with the Pro-Administration leadership, but neither side presented a deal seen as acceptable by all parties. Beauregard would make an impassioned speech about his service to the nation both in the military and in public life, and that he would stand by the Supreme Courts ruling that Slavery was a state’s issue. Yet despite the Beauregard’s pleading the Dixiecrats leadership decided to go with the safer candidate of Zebulon Baird Vance instead. After this decision the Vice President told Reagan he was going to seek the presidency with or without the Pro-Administration’s endorsement. After Reagan wrote the former President Jefferson Davis to tell him of the events which took place to nominate Vance. Davis responds was that of disappointment and concern.

Post-Construction Era

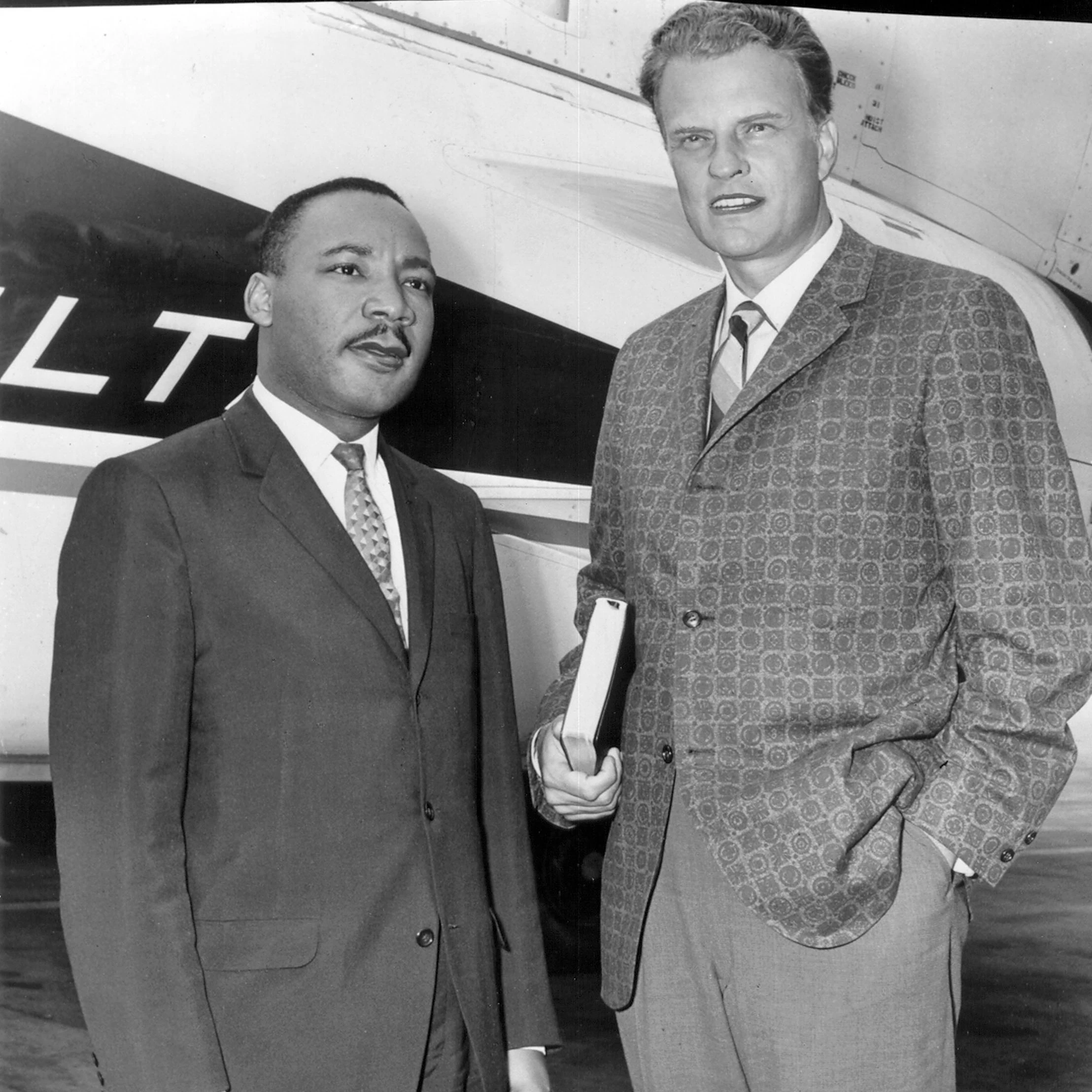

Martin Luther King and Billy Graham. Both men shaped the Confederacy’s moral compass in the 20th and 21st centuries.

The Confederacy won a war against Spain in 1898, after which it took control over the islands of Cuba and Puerto Rico from Spain.

The act of slavery continued in most states until its formal abolition in 1899 by President Tyler. Although slavery was ended, racial tensions were still high and would became a major factor in the coming Confederate Civil War, whose effects can still be felt to this day.

From 1935 to 1943, the country fell into a period of civil war, which resulted in the Confederate government being forced into exile in the United States as the communist government of the Confederation of American Socialist States took control over the country.

The Confederacy was also the location of the The American War (1961–1978), the largest conflict in the history of the New World. The war resulted in the reestablishment of the Confederacy’s authority in the region and the dissolution of the communist regime. The United States took the state of Arizona and part of the state of Virginia from the Confederacy, which were added to the US’s union. This and other policies over the last 40 years have led to political tension between the two American nations.

Since the American War, the Confederacy has made strides in returning its infrastructure from the devastation of war, with the adoption of conservative political and economical reforms to attract international businesses. Since 2000, the Confederacy’s economic growth rate has been among the highest in the world. These factors have made the Confederacy a prosperous local power with hopes of becoming major player in world politics in the coming future.

Another result since the destruction of the CASS was the ending of their state atheism. This has led to evangelical Christians such as Billy Graham and Martin Luther King gaining a major footing in the nation. The Confederacy regained its status of a religious country, with high church attendance and membership.

Politics and administration

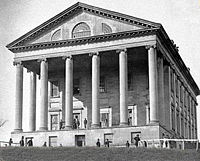

The Confederate State Capital Building in Richmond, Virginia.

The Confederate States are a confederal presidential republic composed of 14 states. The government is divided into three distinct branches: legislative, executive and judicial, whose powers are vested by the CS Constitution in the Congress, the president and the federal courts, respectively. The powers and duties of these branches are further defined by acts of Congress, including the creation of executive departments and courts inferior to the Supreme Court.

Executive: The executive power in the federal government is vested in the president of the Confederacy, although power is often delegated to the Cabinet members and other officials. The president and vice president are elected as running mates by the Electoral College, for which each state, is allocated a number of seats based on its representation in both houses of Congress. The president is limited to a single six year term. The president is both the head of state and government, as well as the military commander-in-chief and chief diplomat.

Judicial: The Supreme Court of the Confederacy was established in 1875, and consists of 15 judges one appointed by each state’s supreme court to represent it on the national level. The final judge is appointed by the President of the Confederacy. Each state’s judge has no term limit, but serves at the «pleasure» of either his state’s Supreme Court or the president that appointed them. The CS Supreme Court decides «cases and controversies»—matters pertaining to the federal government, disputes between states, and interpretation of the Confederate States Constitution, and, in general, can declare legislation or executive action made at any level of the government as unconstitutional, nullifying the law and creating precedent for future law and decisions.

Legislative: Branch consists of two chambers: the House of Representatives and the Senate. The Congress meets in the Confederate States Capitol in Richmond Virginia. Both senators and representatives are chosen through direct election, though vacancies in the Senate may be filled by a gubernatorial appointment. Congress has 188 voting members: 160 Representatives and 28 Senators. The Congress makes federal law, declares war, approves treaties, has the power of the purse, and has the power of impeachment, by which it can remove sitting members of the government.

The Senate of the Confederate States (2018), Dixiecrat in Blue (7 Seats), Readjusters in Gray (12 Seats), Booth in Green (8 seats), CPC in Red (1 seat)

The Senate of the Confederate States of America

| State | Senator | Took office | Party | Predecessor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama |  | Mitch McConnell | January 3, 1985 | Readjuster | Howell Heflin (1979-1985) |

| Jefferson Sessions | January 3, 1999 | Booth | Richard Shelby (1987-1999) | |

| Arkansas |  | John Boozman | January 3, 2011 | Booth | Blanche Lincoln (1999-2011) |

| Tom Cotton | January 3, 2015 | Booth | Mark Pryor (2003-2015) | |

| Cuba | Bob Menendez | January 3, 2007 | Dixiecrat | Rafael Cruz (1999-2007) | |

| Mariela Castro | January 3, 2017 | Communist | Marco Rubio (2011-2017) | |

| Florida |  | Bill Nelson | January 3, 2001 | Dixiecrat | Buddy MacKay (1989-2001) |

| Allen West | January 3, 2017 | Booth | Charlie Crist (2011-2017) | |

| Georgia |  | David Perdue | January 3, 2015 | Booth | Saxby Chambliss (2003-2015) |

| Ben Affleck | January 3, 2021 | Dixiecrat | Doug Collins (2020-2021), Johnny Isakson 2005-2020 | |

| Louisiana |  | Bobby Jindal | January 3, 2015 | Readjuster | Mary Landrieu (1997-2015) |

| John Kennedy | January 3, 2017 | Dixiecrat | David Vitter (2005-2017) | |

| Mississippi |  | Roger Wicker | January 3, 2007 | Readjuster | Trent Lott (1989-2007) |

| Chris McDaniel | January 3, 2015 | Booth | Thad Cochran (1979-2015) | |

| North Carolina |  | Richard Burr | January 3, 2005 | Readjuster | John Edwards (1999-2005) |

| Thom Tillis | January 3, 2015 | Readjuster | Kay Hagan (2009-2015) | |

| Puerto Rico |  | Luis Fortuño | January 3, 2013 | Readjuster | Pedro Rosselló (2001-2013) |

| Zoé Laboy | January 3, 2017 | Dixiecrat | Roberto Rivera Ruiz de Porras (2011-2017) | |

| Sequoyah |  | Bill John Baker | January 3, 2011 | Dixiecrat | Chadwick «Corntassel» Smith (1999-2011) |

| T.W. Shannon | January 3, 2019 | Booth | Elizabeth Herring (2013-2019) | |

| South Carolina |  | Jim DeMint | January 3, 2005 | Booth | Bob Inglis (1999-2005) |

| Nikki Haley | January 3, 2017 | Readjuster | Lindsey Graham (2003-2017) | |

| Tennessee |  | Marsha Blackburn | January 3, 2019 | Readjuster | Bob Crocker (2007-2019) |

| Bill Hagerty | January 3, 2021 | Readjuster | Lamar Alexander (2003-2021) | |

| Texas |  | John Cornyn | December 2, 2002 | Readjuster | Phil Gramm (1985-2002) |

| Beto O’Rourke | January 3, 2019 | Dixiecrat | David Dewhurst (2013-2019) | |

| Virginia |  | Joe Manchin | January 3, 2009 | Dixiecrat | Richard D. Obenshain (1979-2009) |

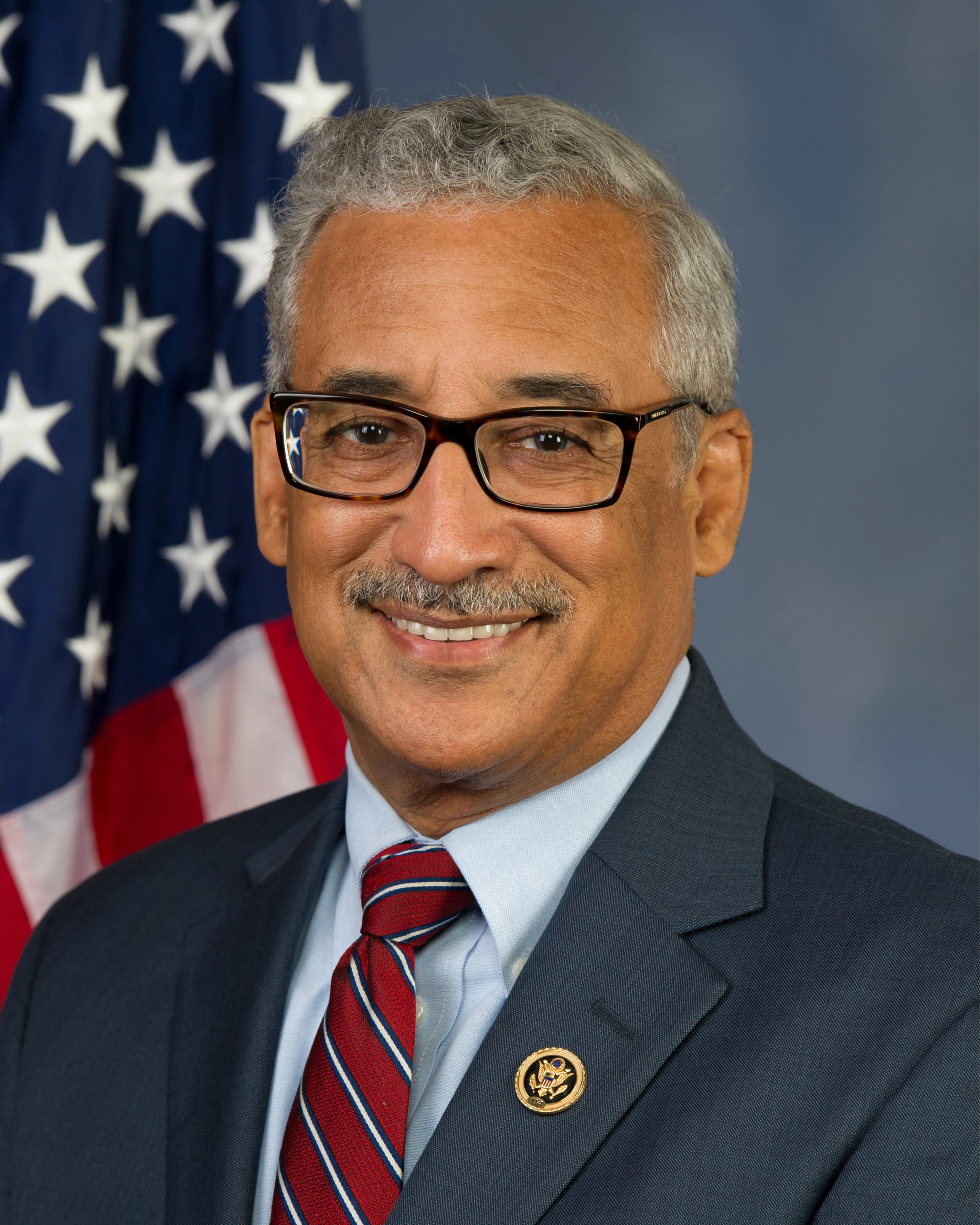

| Bobby Scott | January 3, 2013 | Dixiecrat | George Allen (2001-2013) | |

Congress of the Confederate States (2018), CPC in Red (14 seats), Dixiecrat in Blue (47 seats), Readjusters in Gray (60 seats), Booth in Green (39 seats)

Political parties

In spring 1866 President Davis, his cabinet, and the leadership of the congress that were Pro-Administration would have a private meet to nominate a candidate to be their nominee for the election of that year. Now commonly know as the «Convention of 1866» this would lead to the nomination of Vice President Alexander Stephens and also the establishment of the future cabinet and leadership in the Congress in the coming session. Although Stephen had multiple opponents in the election of 66, he cared every state which historians credit to the endorsements, financial, and political support of those members of the Convention.

In 1872 A second «Convention» would take place with nomination of Vice President Judah P. Benjamin, along with establishment of the leadership for the coming session. Those not supporting the Administration would public criticize these private «Conventions», which Mississippi newspaper mogul William Barksdale coined the term the «Dixiecrat Party» a joke on the nation’s nickname of Dixie, the old Democratic Party, and the fact of a group of aristocrat were dominating the government. He would also make the claim that this political party was far worst then even the former Republican Party of the United States. Yet even with this criticism, Vice President Benjamin would care ever state of the Confederacy. (although Texas almost went to their state’s Senator Louis Wigfall.)

As the Pro-Administration dominated nation politics, as a political party in all but name. Local and State level were having a rise of Anti-Administration political alliances across the nation. Often being made up of politicians from across the political spectrum their common bond was their non-support for the leadership on the nation level. (Among these were the Hornets of Arkansas, the Revolutionaries of Louisiana, Americans of Tennessee and parts of North Carolina, New Republicans of Texas, and the Readjusters of Virginia)

The election of 1878 would result in the Pro-Administration’s nominee of John Reagan being elected president, but unlike he’s predecessors Reagan had not taken ever state of Confederacy, as Arkansas, Tennessee, and Virginia would go to a non-Administration candidate Senator Augustus Hill Garland.

The Pro-Administration now commonly known as the Dixiecrats would make a controversial nomination of Senator Zebulon Baird Vance over the expected candidate of Vice President P.G.T. Beauregard in the election of 1884. Senator Vance was popular in his home state of North Carolina, and was very influential in the Senate, but his greatest strength over Vice President Beauregard was that the Vice President had shown support of ending slavery. (By 1880 Arkansas, and Tennessee had passed laws ending the practice of slavery in there states.) Beauregard trying to earn the support of the leadership of the Pro-Administration arguing that Slavery was a state issue, and that he would not bring it into national politics. Yet the Dixiecrats leadership decided to go with the safer candidate of Zebulon Baird Vance instead. Vance’s was expected to win without much challenge having the support of the majority of the nation top politic machines, but he was ill prepared for his main opponent fellow CS Senator William Mahone. Mahone was a leader of Virginia’s Readjuster and also was a railroad executive. Mahone launched a new kind of campaign using the railroads to actually campaign on a faster and larger scale then in elections prior. He also picked war hero James Longstreet as his vice presidential candidate. The election of 1884 was the closet in the nation history at that time with Mahone winning by a slim margin. (Beauregard also took his home state of Louisiana) During the election Mahone used Readjuster lecture and flags on his trains and campaign stops. So it soon became a name commonly associated with members of the Anti-Administration.

By the turn of the century the political alliance of the Dixiecrats (Pro-Administration) and the Readjusters (Anti-Administration) had become the equivalent of political parties. Although they were rarely separated by political stances, but by social status.

Dixiecrats was the establishment often associated with career politicians and the upper classes. They dominated politics in the Confederacy, but they’re membership political stances was diverse having hardline Conservatives to the most Radical Liberals. Its leadership structure was far stronger then that of political parties of the United States, having a hierocracy from the leadership in Richmond all the way down to the political bosses on the state and local level. Not having conventions allowed for those in power to pick their successors and nominees with the endorsement of the Administration.

The Readjusters were quite the opposite of the Dixiecrats. Following the election of President Mahone, all the major Anti-Administration political alliances put their support behind the president, not because of his political stances, but for the hope he’ll be able to weaken the Dixiecrat’s hold over the government. This lack of a central established leadership Readjusters would make the alliance lack the Pro-Administration’s strict nomination ruling allow for almost anyone could announce themselves as a candidate for the Readjusters. This would create a period of local and states elections with multiple candidates claiming to be Readjuster’s choice. By 1908 many Readjuster state’s leaderships either established local conventions or primaries to nominate their candidates. Readjusters were often popular in poor areas and among Blacks and Hispanics who were often not considered «qualified» candidates for the Dixiecrats.

In 1919, the Communist Party of the Confederacy was founded. In its early years the CPC struggled with attacks by the pre-established Dixiecrats and Readjusters. Also the CPC had trouble getting support among voters who were untrusting of the new party from the propaganda against and the fear of facing a civil war similar to that happening in Russia. The CPC also had trouble finding candidates, many of their earliest were not really Communist, but were candidates who hadn’t won the endorsement of the Readjusters and was looking at an alternative. This would change in the 1930’s.

1929 the Great Depression begins. Confederate President Reece of the Readjusters was ill-prepared for such a crisis. Which resulted with many Confederates lost faith in the Readjuster which showed in the Dixiecrat dominance in the election of 1930. Although they did not gain any seats in the election of 1930 the CPC membership had a massive jump.

The Confederacy knew that the election of 32 was going to be among the most important in the nation’s history. The Dixiecrat Convention expected nominee was going to be Speaker of the CS House of Representatives, but he was going to face the challenge of the 39-year-old upstart Huey Long the Radical Governor of Louisiana. The establishment of the Dixiecrat leadership were behind Speaker Garner, who was going to campaign on a platform based around conservative and pro-business policies. Governor Long held the liberal wing of the party and was campaigning with a platform known as Share Our Wealth, which included many radical liberal policies. Before the Convention and even during it Long threatened to still run even without the Dixiecrat’s endorsement. More trouble was made against Garner’s forces when Senate Majority leader Joe T. Robinson pulled his support behind Governor Long. The Establishment leadership of the Dixiecrats (lead by former President Owen) would create a deal with Long that they’ll support his candidacy for president in return that Garner will serve as the Vice President, and that they’ll appoint his cabinet and the Congressional leadership in the coming session. Long agreed with added stipulation that they will support his Share Our Wealth policies that he was going to campaign on, which Owen agreed to. The election of 1932 would end in a landslide with the Long/Garner ticket caring every state of the Confederacy expect Puerto Rico.

Fallowing the assassination of President Long, the Confederacy fell into political turmoil. As valence became more come and spread throughout the nation elections were canceled, which in turned strengthened the support for the anti-government forces which would become the CASS. In May of 1939 the Independent Convention of Confederation was established in Baton Rouge. The Convention was established by the CPC leadership with fellow delegates made up of different anti-government forces. (Representatives at the Convention included, among others, limited to the Communist Party of the Confederacy, Worker’s Army, the Framer’s Alliance, The Black American League, the Free Cuba Party, the Communist Worker’s Party of Puerto Rico, the Government of Louisiana, and the remnants of the Share Our Wealthers and the Longnites.) Eventually these fractions realizing that none of them would have any kind of majorities, which lead to many on the left to form the Popular Front under lawyer Clifford Durr.

Following the Fall of Richmond in 1943, President Carter Glass would form the Confederate Government in Exile in the United State’s city of Louisville, KY. During its time the «government» would be controlled by the Dixiecrats who were not only the party of President Glass, but also had controlled over the CSA Legislative government at the time of the Civil War. (Although Former President Reece and Minority Leader of the CSA Congress Howard Baker Sr. did hold attain some influence in the government).

During and Following The American War, the Confederate States adopted many of the United State’s partisan policies adopting primaries and US styled Conventions with delegates instead of the Close door Conventions held by the state party bosses. Throughout the 70’s to 90’s the Dixiecrats dominated Confederate Politics winning five out of six of the presidential elections and controlling both the Senate and Congress.

The Dixiecrats would eventually lose that strength in the government with the conflicts between its Conservative and Liberal members for control over party. This would eventually come to ahead at the Dixiecrat Convention of 1992 with the nomination of Governor Bill Clinton over expected conservative nominee Governor George Wallace Jr. This would lead to the Conservative Wing either joining the Readjusters (which had been adopting a more Conservative policies over those years) or would go and form the Booth Party.

Currently the CSA is split between four major political parties.

Subdivision

The Confederate States is divided into fourteen states which are subsequently divided into counties (exceptions are Cuba and Puerto Rico which are split into Provinces, Louisiana which is split into Parishes, Sequoyah which is split into Nations, and Virginia which along with counties has Independent Cities.) Most of the states are called States, but Virginia and Puerto Rico are Commonwealths (Mancomunidad), Texas is a Republic (República), Cuba is a Free State (Estado Libre), and Sequoyah is a Union (ᏗᏌᏊ ᎤᎾᎵᎪᎯ, Disaquu Unaligohi). These names do not indicate any sort of differences in autonomy or government, they are equal for all intents and purposes with each other and regular States.

| State | Population | Area (sq mi) | Area (km²) | Capital | Largest city | Governor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Alabama (AL) Alabama (AL) | 4,874,747 | 52,420 | 135,765 | Montgomery | Birmingham | Kay Ivey | |

Arkansas (AK) Arkansas (AK) | 3,004,279 | 53,178 | 137,732 | Little Rock | Asa Hutchinson | ||

Cuba (CB) Cuba (CB) | 11,209,628 | 42,426 | 109,884 | Havana | Albio Sires | ||

Florida (FL) Florida (FL) | 20,984,400 | 65,757 | 170,312 | Tallahassee | Jacksonville | Ron DeSantis | |

Georgia (GA) Georgia (GA) | 10,429,379 | 59,425 | 153,910 | Atlanta | Stacey Abrams | ||

Louisiana (LA) Louisiana (LA) | 4,684,333 | 52,378 | 135,659 | Baton Rouge | New Orleans | John Bel Edwards | |

Mississippi (MS) Mississippi (MS) | 2,984,100 | 48,431 | 125,438 | Jackson | Tate Reeves | ||

North Carolina (NC) North Carolina (NC) | 10,273,419 | 53,819 | 139,391 | Raleigh | Charlotte | Pat McCrory | |

Puerto Rico (PR) Puerto Rico (PR) | 3,195,153 | 5,324 | 13,791 | San Juan | Alexandra Lúgaro | ||

Sequoyah (SH) Sequoyah (SH) | 1,930,864 | 62,191 | 161,074 | None | Oklahoma | Bill Anoatubby | |

South Carolina (SC) South Carolina (SC) | 5,024,369 | 32,020 | 82,933 | Columbia | Charleston | Vincent Sheheen | |

Tennessee (TN) Tennessee (TN) | 6,715,984 | 42,144 | 109,153 | Nashville | Bill Lee | ||

Texas (TX) Texas (TX) | 30,204,596 | 274,304 | 710,444 | Austin | Houston | Greg Abbott | |

Virginia (VA) Virginia (VA) | 8,470,020 | 42,774 | 110,787 | Richmond | Virginia Beach | Mark Herring | |

Economy

Following the rebuilding of the nation after the American War, the economy of the modern Confederate States of America has become quite different than that of its predecessor, the Confederation of American Socialist States. Since the turn of the century, there has been a growth in the service economy, manufacturing base, high technology industries, and the financial sector. Texas in particular enjoyed a growth in its energy industry. Tourism has also grown steadily since the end of the war in the states of Florida, Cuba and Puerto Rico.

Numerous automobile production plants have been brought to or re-established in the nation, giving much needed jobs to the nation’s citizens.

In medicine, the Texas Medical Center in Houston has achieved international recognition in education, research, and patient care, especially in the fields of heart disease, cancer, and rehabilitation. In 1994 the Texas Medical Center was the largest medical center in the world including fourteen hospitals, two medical schools, four colleges of nursing, and six university systems.

Many worldwide corporations are headquartered in the Confederacy, such as Walmart Inc., Phillips 66, the Coca-Cola Company, PepsiCo, Delta Air Lines, Claxson Interactive Group and Carnival Cruise Lines.

This economic expansion and its traditional industries of agriculture, mining, and oil have enabled the nation to rebuild itself since the war.

Sports

Confederate Football

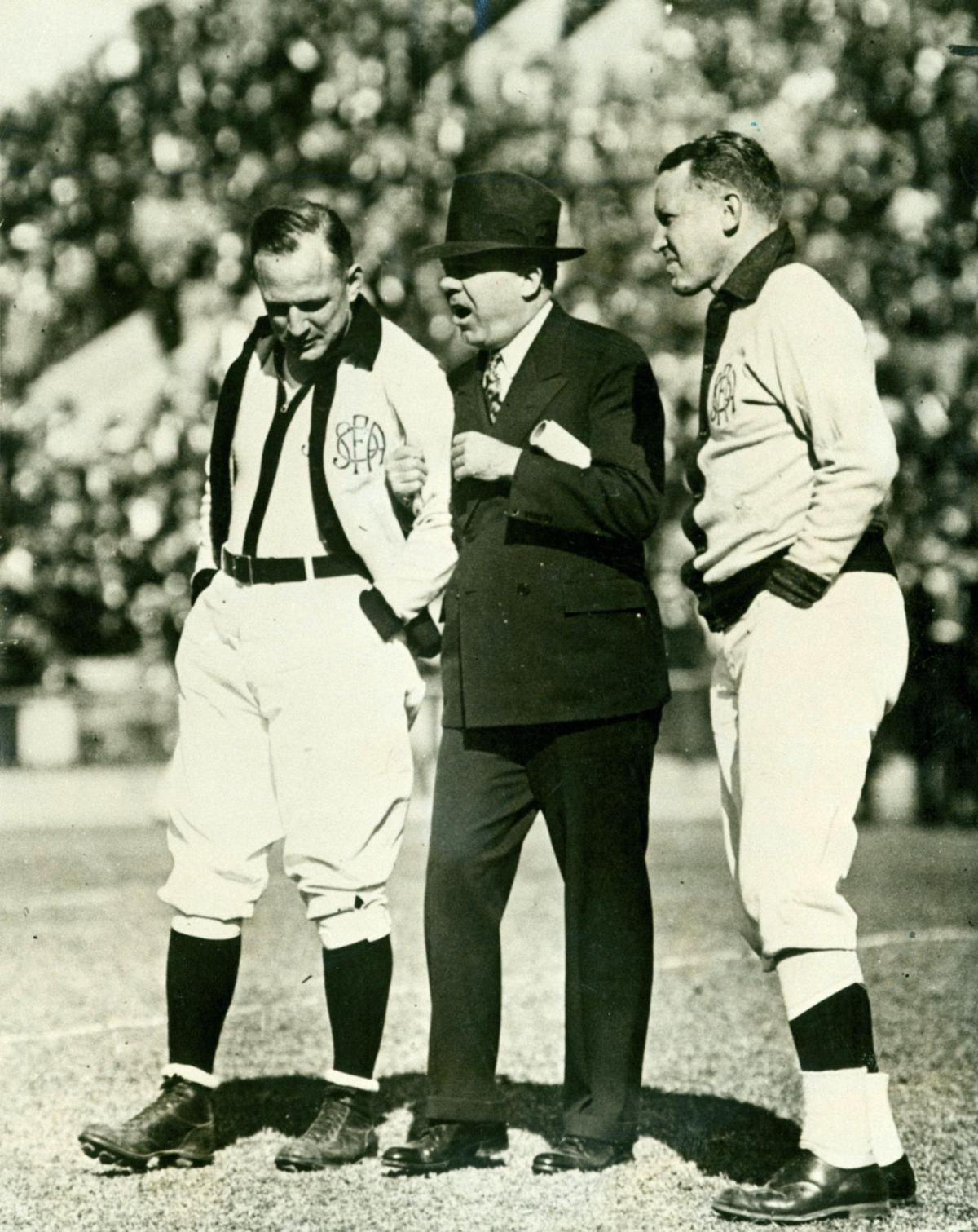

Governor Huey Long with two football referees during the first game using his set of rules for the game